The American-born painter R.B. Kitaj’s reputation as an artist rests chiefly on a sequence of perhaps twenty fully realized paintings. Their complex, many-layered imagery reveals what he called his “teeming neurasthenic mind.” Those works became (in Britain at least, where Kitaj was based for almost forty years) inseparable from his parallel activities as a buoyant polemicist, writer, and curator. He recognized that large-scale compositions of figures (frescos and altarpieces, “history paintings” and grandes machines) had for centuries been at the core of Western painting. Taking another London-based American provocateur, Ezra Pound, as his early model, he embarked on a lifelong project: to continue that tradition and to “make it new.” This aspiration put him on a collision course with the prevailing abstract and conceptual orthodoxies. Three decades of controversy, recognition, and success ended in tragedy.

Ten years after Kitaj’s suicide in Los Angeles, a German publisher has brought out his Confessions of an Old Jewish Painter. The editor, Eckhart J. Gillen, was one of the curators of the superb Kitaj retrospective mounted by the Jewish Museum in Berlin in 2012. From a fragmentary and often repetitive typescript, he has put together a thoroughly readable text. Any thinness is well masked by plentiful illustrations—more than two hundred in all—not only of Kitaj’s works but also his own intimate photographs and those of Lee Friedlander, his lifelong friend. With a preface by David Hockney and Gillen’s epilogue and useful end matter, it is a handsome and necessary volume.

Kitaj’s reputation has remained more stable in Germany than in Britain or America, not least because his early ten-foot-wide masterpiece, Erie Shore (1966), has hung for decades in Berlin’s Neue Nationalgalerie. This monumental diptych, with its blaze of red and orange and its marvelously fluid space, takes as its ostensible subject the pollution of Cleveland’s lake. It inspired several German painters, influencing, for example, the floating collage-like imagery of Sigmar Polke and the quasi-diagrammatic compositions of the young Neo Rauch. Kitaj’s later preoccupation with the Holocaust and “Jewishness” as his central subject matter may, too, have had more urgency in Germany.

“I was born,” Kitaj writes in the first lines of his book, “on a Norwegian cargo ship called Corona slipping out of New York harbor at night, bound for Havana and Mexican ports in the summer of 1950.” He was in fact born as Ronald Brooks in Ohio in 1932, but we learn next to nothing about his upbringing in the 1930s and 1940s in a Cleveland suburb and in the depressed small city of Troy, New York, upriver from Albany. He is “born,” in his view, only when he puts all that behind him at seventeen and embarks on a life of solitary self-creation.

These earlier sections read freshly and pass rapidly through many changes of locale. Enrolled as an art student at Cooper Union in New York City, Kitaj is constantly setting off on yet another Standard Oil tanker (he took thirteen voyages in all); he initiates a lifelong pattern of brothel prowling in dark foreign ports. His Viennese Jewish stepfather, Walter Kitaj, had fled Austria in 1938 alongside Kitaj’s “step-grandmother,” who funds the boy to study at the Vienna Academy. In a Vienna evening class he meets a student of Russian literature, Elsi Roessler, of gentile Austrian immigrant descent but also raised in Cleveland, with whom he has what he calls “my first boy-girl romance…. And so we spent much of that year struggling joyously in bed, just like all other ’50s teenagers in the backseats of Chevys, only that we did it where Hitler began.” Eventually, in New York, Kitaj now “flush with new money from seagoing,” they marry. They return to Vienna, and after a late-summer odyssey through much of North Africa and Spain, they arrive at the little Catalan port of Sant Feliu de Guíxols and decide to winter there.

Kitaj had “always been attracted to the idea of spending years doing a picture,” he tells us, and so “I had carried one bloody canvas, from [New York], to Vienna, to Catalonia, and even beyond.” It was “a ridiculous mélange, very much overpainted, of the half-formed ideas I had stumbled upon,” and in their rented house he worked that “whole blustery winter on it, freezing cold, and the damn picture froze me cold too.”* That failed painting, with its echoes of Surrealism and Pound, clearly presages the “ridiculous mélanges” of Kitaj’s maturity. In this book Sant Feliu supplies an important thread: across fifty years Josep Vicente Romà, the anarcho-socialist and Catalan nationalist who speaks “a wonderful saintly English,” becomes emblematic of the simple, uncorrupted goodness that Kitaj the Immoralist always seeks.

Much about the author’s episodic and discontinuous early life is clarified in these pages. We learn that Kitaj, broke by the mid-1950s, decided to enlist in the army and altogether ceased to paint for two years: “I was not yet ready to be an artist.” Stationed in the forest of Fontainebleau, he made large drawings from photographs of the latest Soviet tanks and hardware. At last, allowed three years of study by the generous GI Bill, he chose in 1957 the Ruskin School in Oxford. He writes of “the sad Ealing Comedy that England was: agreeably sad-gray, cheap, Orwellian, deeply alien.” Attending the legendary public lectures of the art historian Edgar Wind, Kitaj began to be fascinated by arcana about the Warburg Institute, the cultural research center based on Aby Warburg’s idiosyncratically arranged library. Wind understood that Warburg’s descent into the labyrinths of cultural interconnection embodied a kind of mania; and Kitaj began to see ways in which a visual poetry could be shaped out of that mad complexity.

Advertisement

Soon after the twenty-seven-year-old arrived in London, his younger fellow students at the Royal College of Art appointed him their chef d’école. David Hockney has often said that it was Kitaj who offered him a way out of the impasse of abstraction. Their encounter, newly narrated here by both artists, became a kind of parable for the generation of painters that followed them. Hockney, in Kitaj’s account, was “just coming out of the closet” when the older painter asked him: “Why don’t you paint about your own life?” In Hockney’s preface, “I thought, it’s quite right…. I’m not doing anything that’s from me. So that was the way I broke it.”

Other gifted young students, such as Allen Jones and Derek Boshier, were infected by what Kitaj here calls his “disjunct figures”—floating phantom-like forms. However serious their ostensible subject matter—The Murder of Rosa Luxemburg (1960), Isaac Babel Riding with Budyonny (1962)—Kitaj’s early paintings register as, in his words, comical “disparities.” His idiom, like Hockney’s, owed something to the bright graphic design of the early 1960s; even if their true purpose was to renew an art of narrative, both artists were protected under the fashionable new umbrella of “Pop.” “I always got jerked into Pop against my will, kicking and screaming,” Kitaj protests in his Confessions. “Please, leave me and my Jewish neuroses alone, will ya guys?”

The Red Banquet (1960) was Kitaj’s first “History Painting.” In it Herzen, Bakunin, and other nineteenth-century revolutionaries were depicted as wraithlike, half-transparent figures inhabiting a Corbusian villa. A page of handwritten text was attached to the canvas. Reflections on Violence (1962) was a wondrous picture-puzzle. Kitaj called it a “crazy chart,” a phrase that occurred to him while reading the Warburgian historian Frances Yates on the “diagrammatic art” of the thirteenth-century Majorcan philosopher Ramon Llull. He needed to find an equivalent to “the outlandish imagery of such Warburg nonsense-visions.” The canvas had to become a mind-circuit, a container for fragmentary thoughts. On the other hand, in large tableaux such as The Ohio Gang (1964) he eschewed grid and compartment to create a dreamlike flux in which monumental figures morph into one another—a pictorial language partly freed from representation, in which airborne people, objects, and abstract elements interpenetrate.

Both these modes proved immensely influential. In Kitaj’s first London exhibition in 1963 every work was sold; that success was repeated in New York a year later. I have met gifted Kitajites in India and Africa, in Rome and rural Vermont. Yet by 1964 Kitaj was already repudiating his own achievements. In lectures at Cambridge and in London at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, he passionately reproached all current painting as “distanced”—abstract pictures by formalism, figurative ones by irony. He acknowledged that his own compositions were often impenetrable, contrasting them with the direct impact of news photography. (Under attack for their “literariness,” he’d made the fine riposte that “some books have pictures, and some pictures have books.”) Kitaj’s imagery might have seemed even more recondite after he was nourished by new contact in 1967–1968 with post-Poundian American poets like Robert Creeley at Black Mountain and John Ashbery in New York, yet the grace and zest of his seamless flow of forms still carried conviction.

Meanwhile, his family life (he was now the father of two young children) was falling apart. Throughout this book Kitaj’s sexual confessions—half-boastful, half-penitent, but always macho—may, for many readers, be hard to tolerate. In Berkeley he experiences group sex and has multiple affairs with his students; Elsi, he tells us, had her own fling, “so I felt less guilty.” But back in “the immense ugly sprawl of South London,” in “dreary gray Dulwich,” Kitaj could no longer stay put: “Elsi and I were in agony. She began to drink heavily, and I lost myself in women.”

Advertisement

“Then something happened which will haunt me all my days.” In 1969, Elsi committed suicide. Kitaj from then on stopped producing essentially upbeat art. There followed a lacuna of three years from which no substantial painting survives. Instead, a new theme emerged that gives this book much of its bitter flavor: “By 1970 I was to become Jew-crazy.” And later: “I wanted to become the Jew I was.” He reinterprets his own early work: its Jewish protagonists (Babel and Luxemburg); its underpinning by (mostly Jewish) Warburg Institute scholars. “My pictures were declaring the Jewish Question before I, myself, had decided that I needed to be a Jew.” Much of Kitaj’s subsequent energies would be devoted to an investigation of Judaica, from Kabbala to Zionism to the Holocaust.

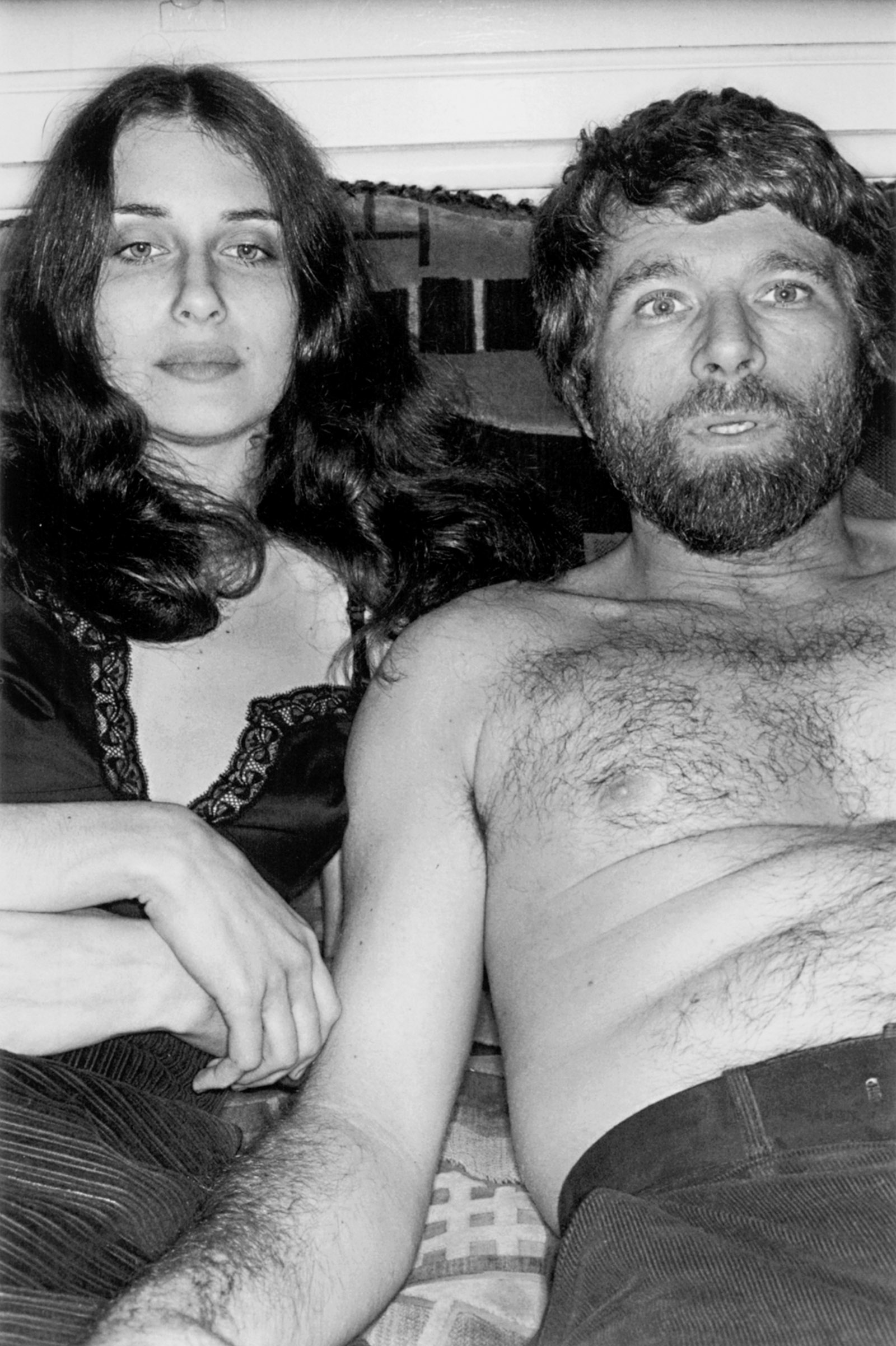

When Kitaj’s painting surfaced again, he was in his forties, and the complex masterpieces of this second flowering are no longer exuberant. We see these new images as though through rain or tears. The art historian Michael Podro observed that the grainy surfaces of these paintings simultaneously convey “both materiality and elusiveness,” allowing Kitaj to move freely between phantasm and fact. The Man of the Woods and the Cat of the Mountains (1973) is his warmest, most intimate picture, unfolding within an almost naturalistic domestic interior. (It declares his new partnership with the young Jewish Californian painter Sandra Fisher.) If Not, Not (1975–1976) remains the most ambitious of all his “altarpieces.” The image prompts a kind of double-take: on closer inspection, a “Venetian farmhouse” on a hill (above what at first appears a gorgeous Golden Age idyll) is suddenly recognized as the gateway to Auschwitz.

“How wonderful it would be,” wrote John Ashbery in 1981, “if a painter could unite the inexhaustibility of poetry with the concreteness of painting. Kitaj, I think, comes closer than any other contemporary.” By then, however, Kitaj had once more stopped painting in favor of several years of drawing—as self-reformation, as penitence: “Sandra quickly shamed me into drawing daily again.” He embarked with Hockney on a campaign to revive life-drawing in art schools. In 1976 he curated “The Human Clay,” an exhibition bringing together over one hundred drawings of single figures by living British artists. However modest the works themselves, the effect of this show—in a London still dominated by the aesthetic of American abstraction—was to relegitimize figuration. The title came from Auden’s Letter to Lord Byron:

To me Art’s subject is the human clay,

And landscape but a background to a torso;

All Cézanne’s apples I would give away

For one small Goya or a Daumier.

In his lively text for the show’s small black-and-white catalog, Kitaj first broached his concept of a “School of London,” one far wider than the current usage of the term—some fifty artists rather than the now familiar six or ten. Moreover he made clear that he was not advocating an art restricted to the single figure (the staple of such painters as Frank Auerbach, Lucian Freud, and Euan Uglow). He writes:

Ultimate skill and imagination would seem to assume a plenitude in painting when the “earthed” human image is compounded in the great compositions, confessions, prophecies, sacraments, fragments, questions which have been and will be peculiar to the art of painting.

In the early 1980s Kitaj did indeed paint further memorable and fascinating large compositions, such as The Jewish School (Drawing a Golem) (1980) and Cecil Court, London WC2 (The Refugees) (1983–1984). But in striving to “reform” his weightless or disjunctive figures, he imposed on them something of the heavy physicality of Auerbach and Freud, and his handling of paint took on a kind of forced impasto. He set out with Sandra for a year of drawing in Paris, adding to his band of Jewish artist-comrades Avigdor Arikha, who painted always in one session directly from his subject. By identifying those doggedly “serious” procedures with a more authentic Jewish striving, Kitaj seemed to be disowning his own collaged and fragmentary art.

Back in London, he became unsociable, entering in the mid-1980s what he would later call his Morbid Period, “during which days on end were depressed in a lachrymose self-inflicted momentum of reading and brooding over the events of the National Socialist Hell” and formulating the notions he would eventually publish as First Diasporist Manifesto. The opening line of that book’s prologue was, “The poor bastard had Jew on the brain,” a quotation from the fiction of Philip Roth, who had become a close London neighbor, sharing and stoking Kitaj’s exilic paranoia.

A mild heart attack led him to take long early morning walks and identify with Jean-Jacques Rousseau, whose Reveries of the Solitary Walker became a favorite text:

He had just emerged from one of the darkest passages of his life, and so had I in early 1990 when I read the slim Penguin edition. There is something truly mad (a terminal paranoia) about this beautiful little book which uncorked some of my own demons and terrors.

Kitaj wrote of wanting to “chase the Black Dog deeper into the shadows of one’s own life,” yet in all his best writing and painting comedy does surface, often a wry self-mockery. On a typical morning walk, he told Richard Morphet,

I’m thinking hard about the painting back on my easel and what I might do to it that will be remembered in art history…. By the time I buy my Herald Tribune at Gloucester Road, Titian himself better watch out. This thought only lasts about five minutes. As I cross the Fulham Road, my nerve has failed and Guido Reni better watch out.

Kitaj was galvanized into new activity as he prepared for a retrospective at London’s Tate Gallery (which would then tour to Los Angeles and to the Metropolitan Museum in New York). He’d spoken of an “old-age style,” although he was only just entering his sixties. He called this style “Drawing-Painting,” in which his heavy graphite line would be perfunctorily colored in. (Munch’s late paintings were one reference point.) When the show opened in 1994, out of seventy-three paintings, thirty-four were images of this kind—in my view few of them essential to the Kitaj canon. He left out several of his early masterpieces (The Red Banquet, for example) and suppressed all his screen-prints. Nevertheless it seemed to me a fascinating show, not least for the commentaries (he called them “midrash”) that Kitaj had attached to many of the pictures, as he had throughout his life.

A retrospective within an artist’s lifetime is always a hazardous enterprise. As reviews appeared, about half were negative, their tone viciously personal. He found himself publicly abused as “cold-hearted,” “ruined by fatal self-delusion,” “flaccid, anaemic,” “pitiable.” His work was “a navel-gazer’s album of me, me, me.” And so on. A generous appreciator of others’ art (he would send enthusiastic postcards even to strangers if he came across work he liked), Kitaj was baffled and wounded. When I met him around that time, he said: “I may not be a great artist, but I didn’t deserve that.”

Two weeks after the Tate show closed, Kitaj returned from visiting his dying mother in America to find Sandra dying from a sudden brain inflammation, leaving him with their young son. From this further shock he would never recover. He attributed her death to the critics: “They tried to kill me, but they killed Sandra instead.” He believed this was connected to a continuing anti-Semitic strain in British culture and that he had been punished as a Jewish outsider. This was the beginning of what Kitaj calls in these Confessions the “Tate War.” In both image and polemic Kitaj attacked his critics, and his continuing rage was evidently the chief fuel for this book’s existence. He delayed his departure for another two years, but “London died for me when Sandra died. It felt like a shabby wasteland which I walked in disconsolate disgust.”

Here I must make an admission. A year after Kitaj’s suicide I was sent his large typescript for comment; I advised against publication unless it was severely edited. Gillen has done his work bravely, cutting Kitaj’s more extreme rants and obsessive repetitions. He has also incorporated a 1997 text, J’Accuse. The effect is to create a far more sane and sympathetic voice than in the original.

“I’ve had 10 years to live with Sandra’s death…. I feel more, or very, human—human without her to protect me from the world…. The buffoon now age 70…. Absurdly human.” Kitaj’s account of his new life among his family in Los Angeles is touching. He has grown a long beard, living a reclusive life beside his pool, which he calls “My Walden.” He has delved further into Jewish mysticism, and (as Gillen makes clear in his epilogue) drawn on that tradition to resurrect Sandra as his female Godhead, his “Shekhina.” His most memorable late sequence of paintings shows the naked couple making new love, as The Angels, Los Angeles.

By 2007, however, Kitaj had suffered from Parkinson’s for three years; medicating irregularly, he must have been vulnerable to severe mood swings. Although a lifelong teetotaler, he bought a bottle of whiskey and accumulated pills. Hockney believes that his suicide was “calculated to the minute.”

Kitaj may have been at his best as an unconscious rather than an overconscious Jew. He sometimes seemed to be working against his own natural gifts, which were those of a brilliant orchestrator of complicated compositions and decompositions. Confessions of an Old Jewish Painter is a performance, a rehearsed retelling of his conflicted life. I’m unsure whether Kitaj’s stature as a painter will be improved by its publication, but the book does add to our knowledge not only of the artist himself but also of the dilemmas inherent in attempting to paint “masterpieces” in the later twentieth century.

This Issue

April 19, 2018

A Mighty Wind

The Question of Hamlet

More Equal Than Others

-

*

Two surviving fragments of this interesting “Teenage Painting” are reproduced in Julian Rios, Pictures and Conversations (London: Hamish Hamilton, 1994), pp. 263–264. ↩