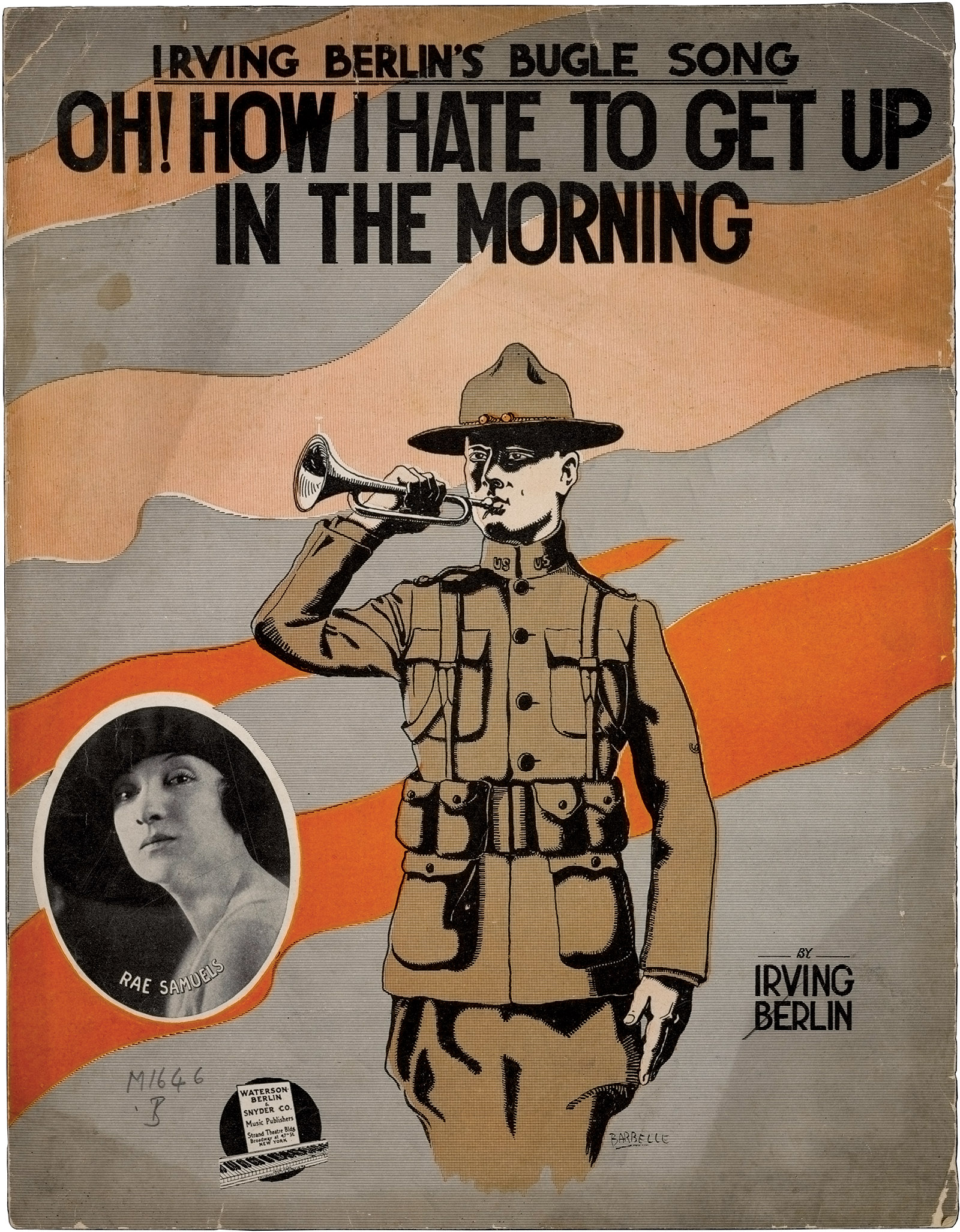

Library of Congress

Sheet music for Irving Berlin’s ‘Oh! How I Hate to Get Up in the Morning,’ from his Broadway revue Yip Yip Yaphank, composed while he was a recruit in the US Army, 1918. It appears in Margaret E. Wagner’s America and the Great War: A Library of Congress Illustrated History, published by Bloomsbury.

War has played a part in literature second only to that of love, as the great lexicographer Eric Partridge noted, because these two experiences have “most captured the world’s imagination.” His observation is quoted by Samuel Hynes in On War and Writing, a diverse collection of essays and reviews, in which he himself adds: “We can never entirely imagine what it’s like to actually fight a war—all war is unimaginable.”

This assertion seems open to challenge. Though it is often suggested that, on the basis of internal evidence in the plays, Shakespeare must at some time have been a soldier, this is unproven. Superb war histories—for instance, those of John Keegan—have been written by people who never saw any combat; likewise some pretty good novels.

Many of us who are historians of conflict undergo a journey from the idiocies of childish romantic delusions toward a glimmer of understanding of realities. Hynes, emeritus Woodrow Wilson Professor of Literature at Princeton and now ninety-three, was a World War II Marine Corps pilot in the Pacific, and has often written lyrically about flight. He displays a just awe for his forebears of World War I, who flew machines of wood, wire, and canvas that killed more of them than did the enemy, because the primitive technology was so unforgiving of what is today called pilot error.

As a junior researcher for a vast 1964 BBC television series on the Great War, I assembled air combat footage, a process that taught me that all the allegedly authentic film material was faked—borrowed from Howard Hughes’s Hell’s Angels and suchlike. Yet that did nothing to diminish my respect for the airmen who did the real thing. One of Hynes’s essays, reprinted here, addresses Cecil Lewis—no, not that C.S. Lewis, but the author of Sagittarius Rising (1936), one of the most celebrated memoirs of World War I. Lewis, born in 1898, was accepted for the Royal Flying Corps while still a seventeen-year-old schoolboy at Oundle. He wrote of his dream of taking to the air, which infused many young men less than a generation after the Wright brothers first exploited the internal combustion engine to lift man from the earth:

To be alone, to have your life in your own hands, to use your own skill, single-handed, against the enemy. It was like the lists of the Middle Ages, the only sphere in modern warfare where a man saw his adversary and faced him in mortal combat, the only sphere where there was still chivalry and honour.

Here was the spirit that inspired America’s most celebrated war flier, Eddie Rickenbacker, though in truth he, like aces of all nationalities, was a ruthless killer who always aspired to shoot his man in the back.

A 1916–1918 scout pilot whom I once met made a case that the machines of that era (they always called them “machines” rather than planes) were better matched to human physical skills and limitations than the much faster ones of World War II and since. And not all his comrades, he observed, were as gung-ho as Cecil Lewis, partly because they recognized that they were almost certain to die.

Arguably the best of all World War I flying memoirs is V.M. Yeates’s thinly fictionalized Winged Victory (1934), a much darker tale than Sagittarius Rising. Yeates died in 1934, aged just thirty-seven, of tuberculosis—known to the Royal Flying Corps as “Flying Sickness D,” one of many medical conditions to which those impossibly wet, cold young men fell victim, about which we never read in romantic narratives. For those who seek a modern take on their ordeal, albeit a blackly comic one, I recommend Derek Robinson’s novel Goshawk Squadron (1971).

Hynes mentions the books of the English Victorian G.A. Henty. Born in 1832, Henty repays more modern attention than he receives, from social historians if not literary critics, because of his huge influence on three generations of schoolboy readers. He served with the British army medical commissariat in the Crimea, and thereafter as a war correspondent in several imperial campaigns, as well as the Franco-Prussian War. Prolific seems an inadequate adjective to characterize the author of 122 books, bearing such titles as Under Drake’s Flag and With Roberts to Pretoria, before his death in 1902.

Though the novels’ admirably sketched historical backgrounds vary, the plots are always the same: a middle-class teenager leaves home to seek his fortune in far-flung places and acquires the skills to disguise himself as a native, to fell a Prussian, Pathan, or Dervish at a hundred paces with rifle or even longbow, and to secure the confidence of generals. The youthful hero survives many adventures before looting an Indian temple or capturing a French Indiaman single-handed, so that he may return home rich to marry Maud or Magdalen and purchase a country estate.

Advertisement

The thread running through the entire Henty oeuvre, fascinating to me at least, is its assumption that the only proper path to success in life for a courageous and ambitious young Englishman is through the exploitation of violence. None of Henty’s protagonists achieves success through honest toil in a warehouse or countinghouse, because the narrative of such a worthy progress would make dreary teenage reading. None of his heroes winds up dead; few are maimed. Though Henty’s pages feature countless battles in which lads fight like tigers and even suffer wounds, nothing is said to suggest that these might cause agonizing pain, much less induce septicemia or terminate the hero’s prospects of raising a family.

If I seem to linger gratuitously on a writer of negligible literary gifts beside those of Yeats, Thomas Hardy, Edward Thomas, and others to whom Hynes devotes essays in this collection, it is because Henty illustrates and mirrors illusions about war that persisted for many centuries, especially among the young. Today cinema, television, and a new literary realism have created a different perception: far from conflict’s horrors being veiled from the folks back home, they are thrust into their faces on giant IMax screens.

And yet this cultural correction can obscure the fact that some young men—and maybe also young women, though their introduction to the front line is too recent for us to be sure—absolutely, sincerely embrace battle. Many war lovers have been pilots, “fighter jocks” of all nationalities. Messerschmitt Bf-109 pilot Hans-Otto Lessing wrote exultantly to his parents in August 1940: “I am having the time of my life. I would not swap places with a king. Peacetime is going to be very boring after this!” The RAF’s Paddy Barthrop similarly recalled the Battle of Britain: “It was just beer, women and Spitfires, a bunch of little John Waynes running about the place. When you were nineteen, you couldn’t give a monkey’s.” A young Royal Navy officer, Lieutenant Robert Hichens, shared the euphoria of those airmen, writing in July 1940:

I suppose our position is about as dangerous as is possible in view of the threatened invasion, but I couldn’t help being full of joy…. Being on the bridge of one of HM ships, being talked to by the captain as an equal, and knowing that she was to be in my sole care for the next few hours. Who would not rather die like that than live as so many poor people have to, in crowded cities at some sweating indoor job?

Hichens did indeed “die like that” in 1942, as did Hans-Otto Lessing a day after writing euphorically about the experience of air combat, but they were both happy warriors. So was Ben Bradlee, who before becoming a legendary editor of The Washington Post served as a destroyer officer in the Pacific, a formative experience. He wrote later: “I just plain loved it. Loved the excitement, even loved being a little bit scared.”

Hynes says: “I don’t write as a military historian. I think of myself as a critic.” Almost all the war memoirs and novels that he mentions with admiration here—Norman Mailer’s The Naked and the Dead, Robert Graves’s Good-bye to All That, Siegfried Sassoon’s Memoirs of An Infantry Officer, Erich Maria Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front, Graeme West’s The Diary of a Dead Officer—display the reflective powers of their authors, together with the torments they experienced.

Hynes hails the Australian Richard Hillary’s The Last Enemy (1942) as the outstanding World War II pilot’s memoir, and this judgment is widely shared. Yet to understand what those young fliers were like, there is a case for some of the scrappier diaries and letters, for instance those of George Barclay published in Fighter Pilot (1976). They lack Hillary’s literary grace, together with the controlled rage that followed the terrible burns he received in a 1940 crash, but Barclay’s record, along with those of others such as Geoffrey Wellum, possesses a simplicity and directness that echo down the years.

A capacity for serious thought sets articulate warriors apart from the vast majority of their comrades. In any study of the literature of war, and especially the poetry of World War I, it seems important to enter the caveat that many fellow veterans resisted and bitterly resented the notion that Graves, Sassoon, Edmund Blunden, and their kind represented the authentic voice of their generation. I have met old soldiers who deplored the poets’ agonizings, muttering between clenched teeth: “Why didn’t they just shut up and get on with it, like the rest of us?” Any library that aspires to span the breadth of conflict experience should include examples of the many memoirs penned by thoughtless young men who—like Henty’s heroes—regarded war as a romp laid on for their amusement, and often sustained such a mentality to their premature graves.

Advertisement

Samuel Hynes is among the historians and critics who regard World War I as a conflict experience distinct from all others. He is assuredly right that it produced more memorable literature. Yet I would submit that this was not because it was qualitatively different or worse for its participants than Rome’s Punic Wars, the Thirty Years’ War, or Napoleon’s 1812 campaign in Russia, but merely because some of the educated civilians in uniform who served between 1914 and 1918 saw what happened to them through eyes quite different from those of the professional warriors—most of them semiliterate—of earlier centuries.

In all ages there is a norm of conduct for and expectation of warriors, which changes between centuries as much as fashions in trousers. Several British World War II generals, Sir Harold Alexander notable among them, expressed a dismayed conviction that their soldiers displayed less guts than their predecessors of the previous struggle, adding a note of regret that they could no longer execute those who ran away.

In modern times Victoria Crosses and Medals of Honor have been customarily awarded for mad moments, single acts of courage. Few warriors, in Western armies anyway, experience more than a year or two of intense combat at most. Yet in the wars of Napoleon, such men as Baron Marcellin Marbot in the French army and Harry Smith in Wellington’s ranks fought for decades, participating in perhaps twenty big battles and countless minor skirmishes.

Moreover, the infantrymen of that era—and indeed of all conflicts between the seventeenth and twentieth centuries, notably including the US Civil War—were required on battlefields to confront each other hour after hour, exchanging volley fire often at ranges of fifty yards or less. My great-uncle wrote to me in 1963 that after reflecting upon a book he had just read about the Waterloo campaign, he believed that nothing he and his kind endured at Passchendaele in 1917 could be defined as worse.

After an action in the 1814–1815 Battle of New Orleans, when British dead and dying lay heaped before the American lines in a fashion no different from that of the Somme a century later, Harry Smith was sent to arrange a truce with General Andrew Jackson’s adjutant-general, Colonel James Butler. The American said to the Englishman as he gazed on the ghastly scene: “Why now, I calculate as your doctors are tired; they have plenty to do today.” Smith riposted outrageously: “Do? Why, this is nothing to us Wellington fellows!” Such was the character of Harry Smith, and such were the duration and bloodiness of the Spanish campaigns through which the rifleman had passed, that his braggadocio authentically reflected the man, and in considerable measure the professional warrior caste of his period.

Having grown up with a reverence for physical courage prompted by my family’s war stories, together with an excess of G.A. Henty, I have since come to believe that mankind wildly overrates the virtue of physical courage, often found in rather stupid adolescent football players. Professor Sir Michael Howard, who won a Military Cross at Salerno in 1943, observed sardonically: “At twenty, there is almost no act of folly one is unwilling to commit, to win an MC.” A Russian sage once said that courage is often the best part of those who possess it. One aspect of achieving maturity, most of us discover, is a recognition that moral fortitude is rarer and thus more precious than the physical variety.

Asked the question, “What is war really like?” we can only suggest fragmentary answers. We may start by disabusing ourselves of illusions about “heroes”—vitally useful and important people for generals, newspaper readers, and indeed societies protecting their interests against peril, but seldom popular with their comrades, because so obviously cast in different clay from themselves.

Samuel Hynes argues that the cartoonist Bill Mauldin was foremost among the authentic GI voices of World War II, and this is partly because Mauldin’s disheveled characters were decisively unheroic. It is not that most of Eisenhower’s soldiers were cowardly, but that they—along with a majority of those who fight all wars—were prone to resist Ambrose Bierce’s wry advice to the aspirant career warriors: “Try always to get yourself killed.”

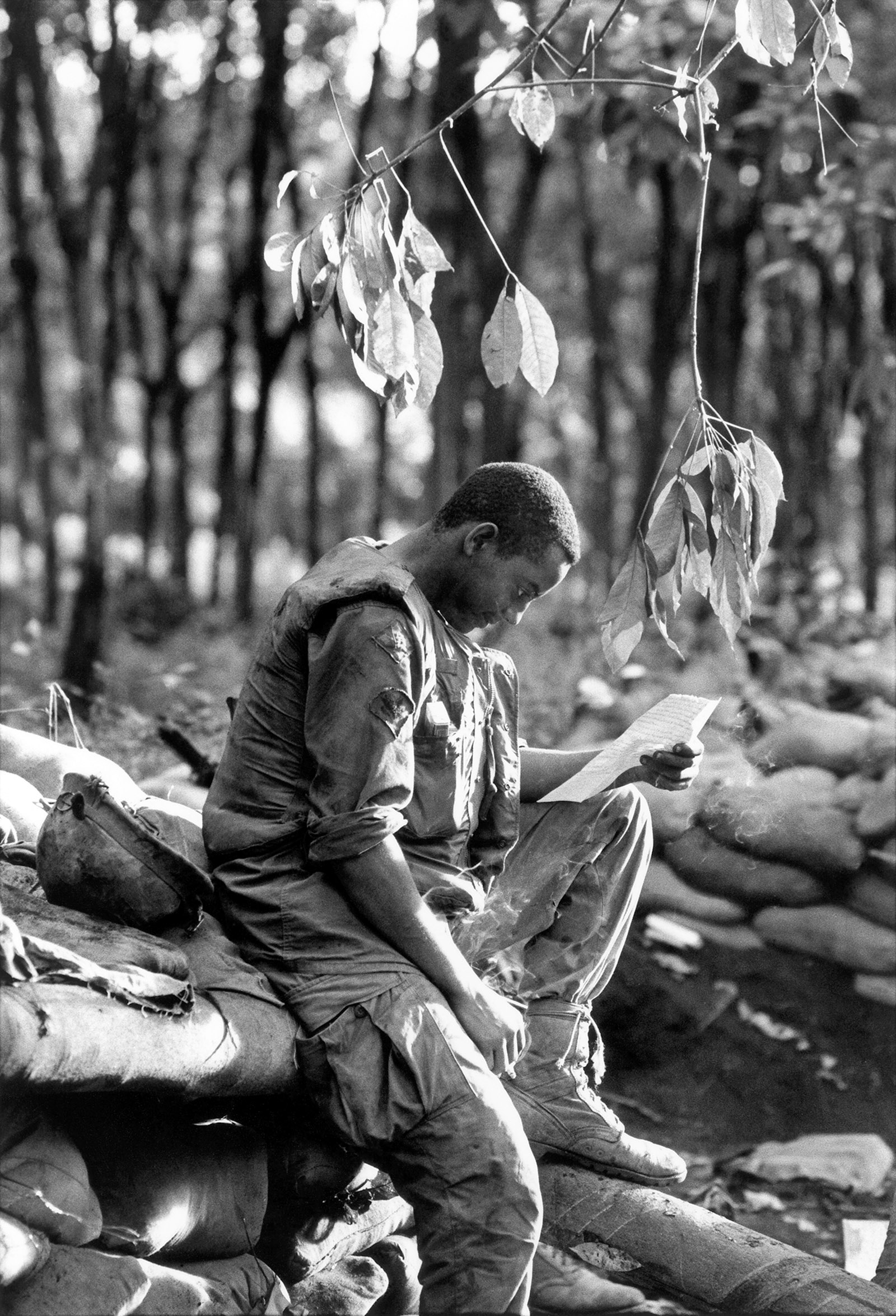

My personal renunciation of the spirit of G.A. Henty was significantly advanced on a day in 1974 when, as a young correspondent, I was driving a jeep somewhere north of Saigon and found myself obliged to halt before a group of South Vietnamese soldiers clustered in the road to dispose of the bodies of enemies they had killed during the night. The entrails of one corpse trailed some distance behind the head as it was dragged bumping through the dust. I thought: If my own stomach was blown open, that is how my entrails would look. It was an unwelcome but intensely vivid reflection, which has lingered ever since.

It is impossible to discern commonality in warriors’ experience of a given conflict, because there are countless variations. The term “war veteran” is used indiscriminately of millions of men who have worn fatigues in a given theater. Yet—since the twentieth century anyway—the overwhelming majority performed functions that may entitle them to a campaign medal, but incurred no greater risks than the everyday ones of civilian life.

There is certainly a shared infantryman’s war from age to age, at the bloody tip of the spear. But artillerymen and tank crews suffer much lower proportionate losses, and those who serve in logistics and support arms are threatened only by jeep accidents, ill-judged sex, and—since Vietnam anyway—bad shit drugs. A majority of the US personnel deployed in Johnson’s and Nixon’s war served in some giant base compound where their worst gripe was the stink in the huts of urinal pipes and JP4 aviation fuel.

Paratrooper Gene Woodley called Cam Ranh Bay “the biggest surprise of my life. There was water surfing. There was big cars being driven. There was women with fashionable clothes and men with suits on…. I said Hey, what’s this? Better than being home.” Navy radarman Dwyte Brown agreed: “Cam Ranh Bay was paradise, man. I would say, Boy, if I got some money together, I’d stay right here and live…. I was treated like a king.” Brown gained forty pounds during his “war service” on a diet of lobster and steak and spent much of his time in the plotting room assembling music tapes for a captain who returned the favor by lending Brown his jeep. Yet in the eyes of posterity, he became as much a “Vietnam vet” as a Marine who fought at Khe Sanh. This says nothing bad about Brown, but helps to explain the impossibility of assembling under one roof “what war is like.”

I felt disappointment on reading Hynes’s observation that “the center of horror in the Second [World] War was on no front at all. Instead it hovered over a number of places: Auschwitz and Buchenwald, Dresden, Tokyo, Hiroshima, Nagasaki.” This assertion reflects a late-twentieth-century preoccupation with the Western sphere of action, attention, death, and destruction.

A new generation of historians, and indeed their readers, recognize that far more people died in wartime Russia and China than in Germany or Japan. Many more Yugoslavs and Greeks perished than did British and American servicemen and civilians put together. Even the Holocaust should be viewed in relation to other unspeakable killings, for instance the deaths of more than three million Russian POWs in Nazi hands. The war’s “center of horror”—if such a thing can be defined—would properly be located somewhere unidentifiable in Russia or China, where no cameras recorded the slaughters, and few articulate witnesses have since emerged to describe events that heaped corpses in millions. Few people who experienced war in those theaters—or, for instance, in northern Europe during the Thirty Years’ War—would have echoed the enthusiasm of Ben Bradlee or Paddy Barthrop for purchasing equity in a global conflict.

There is no more chance of satisfactorily considering the nature of war in a single volume, especially an arbitrarily selected collection of essays such as this one, than there is of capturing the nature of love. But the excellent Samuel Hynes has gathered some entertaining and provocative reflections, rooted in his long life and wide experience of both literature and war. I have never encountered a better summation on this theme, which is as old as time or at least as Homer, than that offered by the Norwegian World War II resistance fighter Knut Lier-Hansen seven decades ago:

Though wars can bring adventures which stir the heart, the true nature of war is composed of innumerable personal tragedies, of grief, waste and sacrifice, wholly evil and not redeemed by glory.