In 2012, as he ascended to the top of the Chinese Communist Party and its government, Xi Jinping began giving speeches about a “Chinese Dream”: China was to become wealthy, powerful, beautiful, and unified. Of these four goals, wealth and power were especially important because, in an official narrative that had been repeated for decades in schools and the media, China for too long had been bullied by Western powers.

The sense of national humiliation that has seeped into popular consciousness in China has, for many, led to a deep ambivalence toward the West: Chinese admire its wealth, modernity, and freedoms, yet we are rivals, not friends. China’s great modern writer Lu Xun (1881–1936) several times observed that his fellow Chinese look either up at the West or down on it—never straight across. The usual results are caricatures that further impede the possibility of getting a clear look.

In the last ten years, there have been signs in China that a growing number of people want to move beyond the look-up-or-look-down trap, and the popularity of Eileen Chang’s novel Little Reunions is one of them. Finished in 1976 but not published until 2009, fourteen years after her death, the book sold 700,000 copies in China in its first six months of publication. It is Chang’s most autobiographical work, so some of its allure has been as a trove of clues to the author’s life. More than that, though, the novel recalls a vanished China of the 1930s and 1940s that was both rooted in Chinese culture and open to the West; its scenes offer an antidote to the mood of indignant rivalry and, at least in the imagination, an alternative to the Xi Jinping version of what it means to be a modern Chinese. In Chang’s assured cosmopolitanism, Westerners are neither models nor victimizers but three-dimensional human beings who go through pains and triumphs just as Chinese people do. Writing in California during years when her home country was writhing in torrid “class struggle,” Chang depicts everyday human experience in prose that is elegant, erudite, and trenchant.

Born in 1920 into an elite but declining family of scholar-officials, Chang grew up with only intermittent parenting by a mother who was often traveling abroad and an aloof father who spent considerable time with opium and courtesans. Following her Western-style schooling in wartime Shanghai and Hong Kong, she began publishing brilliant short novels—Love in a Fallen City and The Golden Cangue, among others—that are reminiscent of Austen in their preoccupation with romantic and family relationships portrayed against a backdrop of upper-class dysfunction in a semicolonial world. Chang quickly found a large following. She remained in China for three years after the Communist victory in 1949, and in The Rice-Sprout Song and Naked Earth produced two of the most penetrating accounts of those years. Her works were banned in China until the 1980s. Then, in the 1990s, as readers thirsted for an alternative to the mediocre entertainment fiction of the post-Tiananmen era on the one hand and the jaw-breaking modernism of the avant-garde on the other, an “Eileen Chang fever” took hold.

Little Reunions follows Julie Sheng—the fictionalized Eileen Chang—through a thick web of relationships in war-torn upper-class China and eventually into a passionate romance and doomed marriage with a Japanese collaborator who is distracted by his several other sexual liaisons. The English translation appends a “Character List” of 124 entries, and it is needed. Julie’s integrity and moral insight give the novel some unity, but it is a kaleidoscope.

Chang approaches her characters, whether Western or Chinese, ready to empathize. Colonists have their problems, too. By showing their vexations (without condoning their faults) Chang asserts a moral power that rejects victimhood. She seems aware that scolding the conqueror is only another way of acknowledging his privileged position. Her empathy serves to vindicate the nation and culture from which she has emerged.

For example, Chudi (Judy), who is Julie’s surrogate mother, has a secret affair in wartime Shanghai with a Nazi school principal, Herr Schütte. He pays for her braces, a marvel of Western technology that improves Judy’s looks more than anyone thought possible. In return, after Germany loses the war, Judy helps Schütte to buy his fare home by selling his greatcoat. Such barter between lovers trumps—at least temporarily—the caste system within which they live. Part of Herr Schütte wishes to be free from that system, but entrenched racism warps his world in ways that are too fundamental for him to notice. When his German wife gives birth to a son in Shanghai, the couple nickname the boy “the Chinaman.” For Chang, the detail of the nickname is a tool for showing the tensions that exist in his mind: a mocking parental love, racial exultation, and creeping cheater’s guilt, among others. She shows Herr Schütte’s human yearnings and their perversions just as she does for her Chinese characters.

Advertisement

Chang’s equitable worldview, made possible by her bicultural background, does much to explain why Little Reunions sold so well when it appeared in 2009. Many middle-class Chinese readers, wealthier and better-informed than their predecessors but feeling morally adrift, hoped for a vision of enlightened forgiveness and dignified equality with the West. Such a prospect was a bracing alternative to the draining tantrums about national humiliation and payback that suffused the Internet and continued to appear in state-approved books like Unhappy China, another best seller in 2009.

The 2009 “fever” over Little Reunions was part of a longer-term trend that has been called “Republican fever”—“Republican” refers to the years 1912–1949, when the Kuomintang (KMT) ruled most of China, and sometimes refers also to Taiwan and Hong Kong after 1949. Before Little Reunions, there had been fevers over the classic stories of Eileen Chang; over Qiong Yao, a Taiwanese writer of romances; Jin Yong, the master of historical martial-arts fiction from Hong Kong; and Teresa Teng, a Taiwanese crooner of love songs. For young people, these artists seemed to be lifting a curtain on another way to be Chinese; for older people, they recalled a bygone time whose cultural resources, after the Maoist blight, might once again prove useful.

An important issue in the fascination with the Republican era has been questions about what really happened among the Nationalists, the Communists, and the Japanese during the War of Resistance (1937–1945) and the ensuing Civil War (1945–1949). Was it true, as the Communists claimed in their textbooks and novels, that their guerrilla fighters expelled the Japanese? Or as historians and journalists were now discovering, did Nationalist troops do most of the fighting?

In 1984 the government built a museum in Nanjing to commemorate the horrific 1937–1938 “Nanjing massacre” in which Japanese troops slaughtered as many as 300,000 noncombatant Chinese. Now, though, writers were comparing that massacre with the Communists’ 1948 siege, during the Civil War, of the northeastern city of Changchun, where a similar number of innocents died, in this case of starvation. On the Changchun disaster, Communist textbooks note only that “Changchun was liberated without a shot.” In a 2007 essay Liu Xiaobo, China’s Nobel Peace Prize laureate who died in prison last year, argued that the Communist government’s lies about the war made Japanese lies about the war more plausible.*

Chinese readers’ sense that they had been lied to about the war fueled a desire to reexamine the Republican years more broadly. Were they really as bad as official textbooks claimed? After 1949 Mao had started violent political campaigns, a famine that killed thirty million or more people, and a devastating Cultural Revolution. Was “liberation” really better than what had gone before?

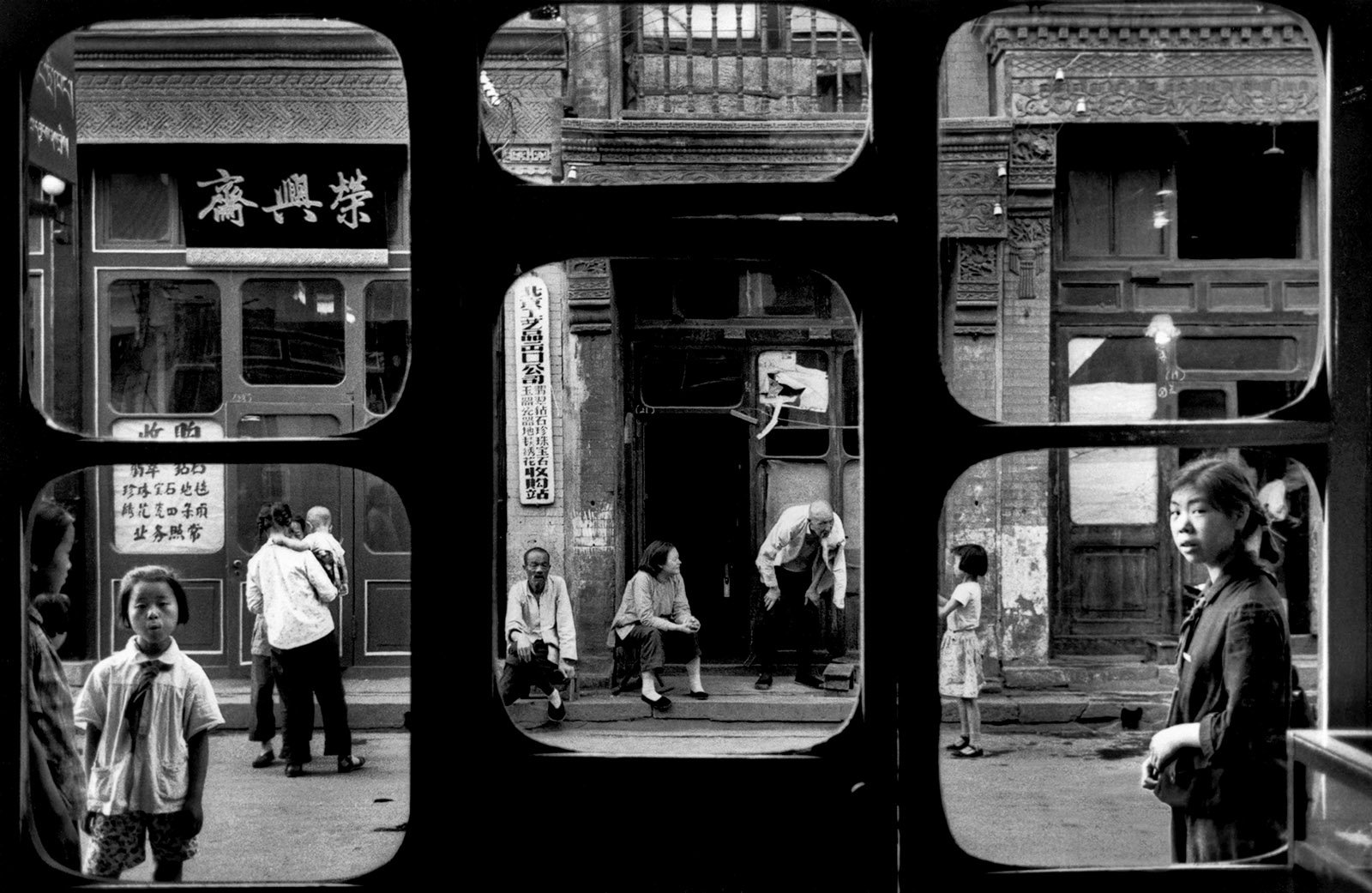

The urban young not only began to imitate Republican-era fashion—such things as qipao gowns, high-heeled shoes, and wire-rimmed glasses with round lenses—but sometimes chose to write Chinese in traditional characters rather than the simplified characters that the Communists had introduced in 1955. Shopkeepers took to using traditional characters on their signs until the government banned the practice in 2015. Intellectuals looked to the Republican era for possible remedies for contemporary moral bankruptcy and cultural malaise. Some sought out Republican-era textbooks to give their children for extracurricular reading.

New editions of the works of intellectual luminaries from the Republican period—including Liang Qichao (1873–1929), the polymath humanist-reformer; Cai Yuanpei (1868–1940), the president of Peking University and famous champion of academic freedom; and Chen Yinke (1890–1969), the preeminent China historian of his time—appeared sporadically through the 1980s and 1990s. The trend accelerated between 1999 and 2013 and eventually included dozens of distinguished writers. In 2011 a three-volume work by Yue Nan called Crossing to the South and Returning to the North compared the fates of Republican-era intellectuals who went to Taiwan or abroad in 1949 with those who stayed behind, and between 2013 and 2016, four volumes by Tian Xiaoqing called Currents in Republican Thought appeared.

These publications made political comments in two ways: first, they spotlighted Republican-era liberal thinkers who had envisioned a different route for China. Reexamining their works in the present raised the question What if…? Second, and more subtly, Republican liberals were useful for those who wished to comment on the present. A writer in the Xi Jinping era might be barred from calling explicitly for certain intellectual freedoms but could show how far liberals in the Republican era were able to go. He or she might know full well that the freedoms back then existed mostly in spite of the government, not because of it, but the goal was to make a point about today.

Collected works of scholars were attractive only to the very well educated, but Republican fever spread beyond the elite, to popular books and articles and middlebrow television shows. In 2015 a three-volume work called The Deeply Historic Republican Era by Jiang Cheng claimed on its front cover to be “recommended by one million readers on the Web.” Yuan Tengfei, a high school history teacher in Beijing, used the Internet to charm people with his sharp insights, delivered with sprightly sarcasm, into every decade of twentieth-century Chinese history. In one of his barbs, he juxtaposes Chiang Kai-shek’s “white terror” of 1927, in which several hundred Communists were massacred, with Mao’s slaughter of 710,000 counterrevolutionaries in 1950, then poses the question, “How many do you have to kill in order to attain the level of Great Leader?” Before his social media accounts were shut down in September 2017, Yuan had 16 million online fans.

Advertisement

On Weibo, China’s version of Twitter, the philosopher and diplomat Hu Shih (1891–1962) loomed as the image of the flawless scholar-official, unswerving in his defense of tolerance and academic freedom in the face of political interference. People noted that Chiang Ching-kuo (1910–1988), the son of Chiang Kai-shek, helped bring democracy to Taiwan in the late 1980s—the very era when mainland politics were moving in the other direction, culminating in a massacre of pro-democracy demonstrators on June 4, 1989. The Republican comparison fed a growing public perception that the Nationalists were not, after all, as bad as the Communists, who seemed to stop at nothing to maintain their grip on power.

But comparisons to the Republican past could also go too far. A contrast with the ills of the Communist era could lead to nostalgia for only its better side. Thus Mao’s extreme violence could make Chiang Kai-shek’s seem less notable; the obscene wealth of the Communist elite today could adumbrate the severe social inequality of the Republican era. Disillusionment following the discovery of Communist lies could lead pro-democracy intellectuals to lurch uncritically in the opposite direction. Because Mao’s spectacular human rights abuses were perpetrated in the name of economic justice, for example, some were led to dismiss concerns over economic inequality as resurgent Marxist baloney in disguise.

Most Chinese fans of Republican nostalgia, though—notably including Eileen Chang fans—have better-grounded views. They can see the difference between Chiang Kai-shek and Chiang Ching-kuo and are admirers of Taiwanese democracy. The author of Little Reunions does not tell her readers what to think, but a left-leaning sympathy with the underclass can be inferred from her art. Masters and servants in her pages live in everyday proximity, and exploitative relationships, although not labeled as such, are obvious. Maids are taken as concubines. Nannies substitute as parents. Septuagenarian servants, having outlived their utility, are abandoned to the destitute countryside from which they originally were drawn. The servant-to-serf continuum shows no real difference from life in Cao Xueqin’s great novel Dream of the Red Chamber, of two hundred years earlier. No careful reader of Little Reunions in 2009 could have used it to look back on Republican life as idyllic or to see the class issue as a mere Marxist obsession.

What Little Reunions does do, along with similar works in the Republican fever, is to invite a counterfactual question: Could China have taken a different path in the twentieth century? What if Japan had not invaded and the Republican effort at modernization had not been aborted? How wealthy and strong might the country have become, how happy its citizens, how attractive its soft power? Beneath these questions about modernization has lurked another about China’s cultural identity: How much Chineseness was lost when the Republic collapsed on the mainland? In the 1950s Mao began to model China after the Soviet Union. Later he split with the Soviets, but the country has suffered cultural confusion and moral malaise ever since. The Republican era, whatever its flaws, seemed the last in which an authentic China could be found.

In 2013 China’s authorities began pushing back against Republican fever. A set of instructions called “Document No. 9” was circulated internally to officials around the country. It warned against “constitutional democracy,” “civil society,” “press freedom,” “historical nihilism,” and other maladies that had been seeping into China. The phrase “historical nihilism,” which seemed puzzling at first, was political code for denying the glorious record of the Chinese Communist Party. Censors set to work enforcing Document No. 9, and two years later Republican fever began to recede.

This year, though, the release of an unusual movie has begun to revive it. One of China’s leading universities, Tsinghua, marked its hundredth anniversary in 2011, and it commissioned a fiction film, directed by Li Fangfang, to celebrate its history. Called in English Forever Young, it is technically awkward, even amateurish, but it tells the important story of how war and revolution ravaged Tsinghua’s humanistic beginnings, and it pleads for the restoration of those values today. Completed in 2012, the film was blocked by censors until January 2018, but when it was released it quickly became a box-office hit.

Tsinghua was founded in Beijing as a preparatory school for Chinese students who were headed for the United States on the Boxer Indemnity Scholarships that were established with funds that China’s last dynasty, the Qing, was obliged to pay to the US as reparations for American losses in the Boxer uprising of 1899–1901. In 1924, the year before Tsinghua instituted its four-year college curriculum, the Indian poet Rabindranath Tagore visited the campus, where, according to Forever Young, he left students with deep impressions of humanistic values. “Do not forget your vocation,” he urges in the film, and avoid “the lure of profit.”

After the Japanese invasion of northern China in 1937, Tsinghua merged with Peking University and Nankai University in Tianjin; the schools transferred their students and teachers to the southwestern city of Kunming to form Southwestern Associated National University, where, in the film, asceticism, patriotism, honesty, and intellectual integrity are paramount. The environment is rustic and simple. Nationalist soldiers are preparing to fight the Japanese, and the US military is helping to train them. The Americans are appropriately gruff, but for a PRC film to show either them or Nationalist soldiers as good guys is a first for PRC cinema.

After the war, back in Beijing and under heavy Soviet influence in the 1950s, Tsinghua’s purpose became the training of engineers, and it did this until 1966, when Mao’s Cultural Revolution shut China’s universities down. Tsinghua reopened in 1978, after which the humanities made a modest comeback. But science and technology have still predominated.

The apparent mission of Forever Young is to revive Tsinghua’s humanist roots. The film opens with scenes of modern furniture and equipment inside clean modern buildings inhabited by people who do not trust one another. Is the baby formula fake? Why did a pork shop where I’d been a loyal customer for four years trick me into buying fatty pork? Look at our “great masters” of Chinese culture today: they are semiliterate soothsayers who, in picking names for infants, recommend words that connote “fiend” or “femme fatale.” Where are the real cultural masters we once had?

Moving back in time, the film invites the question of what caused the ethical and intellectual wasteland we see today. Was it imperialism and war? Did we have no room for anything but patriotism? Through several episodes the film shows that there need be no conflict between humanism and patriotism. Shen Guangyao, a Tsinghua graduate who has enlisted in China’s air force and whose plane is fatally hit in a dogfight, chooses to crash into a Japanese ship rather than bail out with his parachute. He does this of his own volition and in spite of his training by an American military officer that a pilot’s life is always more precious than an airplane. The contrast to the fate of Japanese kamikaze pilots is plain—but so, for Chinese viewers, is the contrast to the endlessly repeated Communist stories about martyrs who forfeit their lives for the party.

Another episode follows a young woman whose small mistakes lead to political charges that result in her social ostracism, torture, and, eventually, suicide. Is this a reference to the Cultural Revolution? Of course. But that cannot be made explicit in the film; it would be “historical nihilism.” Rather these scenes are moved up about five years, to 1962. One can only imagine the negotiations between the filmmakers and the censors on this point.

And on many other points as well. The humanist values that the film shows to be deep in Tsinghua’s origins are in part Christian. The university’s president from 1931 to 1948, Mei Yiqi, was a Boxer Indemnity scholar in 1909 who studied electrical engineering at Worcester Polytechnic Institute in Massachusetts and became a Christian in 1912. In the film we see the unassuming and kind Mei at Southwest Associated University, where we also meet an American missionary who is close to the local Chinese Christians and sings “Amazing Grace” with them. For the film, the lyrics are changed to remove any specifically Christian connotations. The new words in the opening lines are:

Amazing grace flows into my heart

As heaven and earth look on

That grace unfolds for all to see

From here to the edges of dawn

Stripped of hope and tested by fire

My faith still leads me on

Through exhaustion, over dangers

Until every cloud is gone

It cannot have been easy to get the censors to accept the song, whatever the words. Most remarkable, moreover, is that its melody is played, without words, in the background of scenes in the two later historical settings of the film—the Mao era and contemporary times. The tune seems to be saying: “the Tsinghua spirit endures.”

Christianity is only one component in that spirit, though; its general message of truth, justice, and civility is secular and broad. In fact it comes close to what Document No. 9 denounces as “universal values.” The film’s name in Chinese is highly significant: wuwen xidong, which literally means “not asking if it’s West or East,” echoes an idea that has been at the heart of human rights advocacy in China ever since the astrophysicist Fang Lizhi declared, in the late 1980s, in an allusion to the universality of human rights, that “I don’t do Eastern physics or Western physics; I do physics.”

The filmmakers had cover for their provocative title because the phrase wuwen xidong appears in the third stanza of Tsinghua’s school anthem, composed in 1923. But that cover itself was ambiguous: Did it not also suggest that universal values were in the Tsinghua spirit right from the beginning? That question is potentially embarrassing to Chinese leaders like Xi Jinping or Hu Jintao, the president before him, because both are Tsinghua graduates. Which is wrong, they might have to ask themselves—their school spirit or Document No. 9?

-

*

Available at http://www.liu-xiaobo.org/blog/archives/18814. ↩