If you grew up, as I did, in the 1960s and 1970s, watching (albeit through a child’s eyes) the civil rights movement notch victory after victory, you could be forgiven for thinking at the time that that happy condition was normal. By high school, in the late 1970s, I began reading some history and learning about the struggles people endured to win the right to vote in this country. I thought then that these battles were over and done and won—that a new consensus had been achieved.

This state of affairs extended into the 1980s, and my view was reinforced by the observation that even conservative Republicans seemed to share in that consensus. Ronald Reagan backed the Voting Rights Act, signing into law in 1982 significant amendments to the original 1965 act. The most notable change made it easier for plaintiffs to sue states and localities under the act’s Section 2, which affirmed that they did not need to prove discriminatory intent in voting laws, just discriminatory effect. Jesse Helms mounted a lonesome filibuster in the Senate, but even he stood down. The bill passed both houses of Congress by large bipartisan margins. “As I’ve said before, the right to vote is the crown jewel of American liberties, and we will not see its luster diminished,” Reagan remarked when he signed it.

But in retrospect, that moment, in June 1982, may have represented a zenith for voting rights in the United States. Even as Reagan was signing those amendments into law, others on the political right were devising ways to reverse this progress. The standard method was to challenge the Voting Rights Act in court, which produced mixed results at first but in recent years has met with great success, from the Republican Party’s point of view: in 2013 the Supreme Court ruled 5–4, in Shelby County v. Holder, that certain burdens imposed by the act on states and localities with a history of discrimination in voting laws no longer reflected reality—that such discrimination was no longer a problem in the United States. That assessment was a bit optimistic. One measure: in heavily black and Latino counties covered by the Voting Rights Act, there were 868 fewer polling places in 2016 than in 2012, according to a report by the Leadership Conference for Civil Rights. (Before Shelby, covered counties had to get Justice Department approval before they could make such moves.)

In other words, from the moment that black Americans finally won voting rights equal to those of white Americans, a significant number of white Americans started fighting to undo them. My teenage self was quite naive. Forty years later, it appears that what I thought was the new normal was in fact an aberration, a quick little burst of sunshine punctuating an otherwise bleak sky. There is no new consensus and never has been. There is just the old racist consensus, which was successfully pricked for a couple of decades but reasserted its dominance with the help of the many millions of dollars pumped into right-wing foundations and think tanks and activist groups like the Federalist Society.

Most of this activity emanated from the places you might expect—Texas, notably, and the deep South (Shelby County is in Alabama). There were and are some northern states involved, when their governors’ mansions and state legislatures have been taken over by Republicans. Wisconsin under its current governor, Scott Walker, is the most conspicuous northern state to attempt various voter suppression efforts, including one of the country’s strictest voter ID laws, a newer weapon in the arsenal. A study by two University of Wisconsin political scientists found that the state’s ID law kept perhaps 17,000 citizens away from the polls in 2016, in a state Donald Trump won by around 23,000 votes.1 (Walker is seeking a third term this year, and as of late September was trailing his Democratic challenger, Tony Evers, by four or five points.)

But the brutal ground zero of the voting wars, their Stalingrad, is North Carolina. This might come as a surprise, because North Carolina, though southern, is no Mississippi: it has lively cities and a diverse population and great universities and funky, artsy Asheville. It is surely among the most cosmopolitan of the states of the former Confederacy.

But it is precisely for these reasons that the state is contested. Unlike in South Carolina, Democrats can win there sometimes. Barack Obama won there in 2008. His narrow victory over John McCain was the first for a Democratic presidential candidate since Jimmy Carter in 1976 (Bill Clinton never won the state), and only the third in the previous twelve elections. It demonstrated how a Democrat can win in North Carolina: generate a high turnout among African-Americans, somewhere close to 25 percent of the overall vote, and win almost all of it; then take at least one third of the white vote. Obama’s win was narrow—less than a percentage point—but it showed that the state was suddenly in play, no longer reliably red. Also around that time, thanks in part to George W. Bush’s unpopularity, Democrats improbably controlled as many as eight of its thirteen congressional seats. Republicans wanted to shut this down.

Advertisement

In the following few elections, after the rise of the Tea Party, the Republicans roared back to power in North Carolina. In 2010 both houses of the state legislature flipped from Democratic to Republican control, a result in part of the Republican Project Redmap.2 Once they had those majorities, the Republicans drew new congressional districts for the 2012 elections to give them ten of the thirteen seats, and ten is the number they now hold. Also in 2012, the incumbent Democratic governor chose not to run for reelection, and Pat McCrory, an extremely conservative Republican, won that office. Obama lost the state to Mitt Romney that year by two percentage points, despite having brought the Democratic convention to Charlotte that summer. Then in 2014, Democratic senator Kay Hagan lost to Republican Thom Tillis, lately observed speaking up in defense of Brett Kavanaugh’s nomination to the Supreme Court as a member of the Senate Judiciary Committee.

With their new power, North Carolina’s Republicans began implementing a radical agenda, one that stunned many observers. They made large cuts to social programs and public education. They tried to pass a bill ostensibly combating Sharia law, to which they attached several abortion restrictions; when that bill failed, they attached many of the same restrictions to a motorcycle safety bill. They passed the infamous “bathroom bill” calling for the policing of public restrooms to prevent transgendered people from using the facility of their choice, which brought recriminations from even the NCAA and the National Basketball Association. (Tillis, incidentally, was the state house Speaker who helped push all this through.) It was in early 2013 that the state’s progressives started their “Moral Mondays” sit-ins at the capitol in Raleigh, led by the charismatic Reverend William Barber II.

The biggest issue of all, though, was voting rights. North Carolina’s Voter Information and Verification Act (VIVA) of 2013—which the state’s Republicans felt emboldened to pass, it should be noted, after the Supreme Court’s Shelby decision—was a sprawling piece of legislation that included some noncontroversial modernizations. But it also limited early voting, excluded the use of certain forms of identification, and took a few other steps clearly aimed at reducing black turnout as much as possible. Republicans denied this, of course, insisting that they were trying to fight voter fraud. But voter fraud, as numerous studies have shown, is wildly inflated by Republicans and in fact virtually nonexistent. A 2014 Washington Post study turned up only thirty-one credible instances of a voter intentionally impersonating another voter—out of one billion votes cast.3

Allan J. Lichtman discusses VIVA at length in a chapter late in The Embattled Vote in America, while his earlier chapters provide a rich historical background to the law. Lichtman is a historian at American University who has been a long-time commentator on current affairs. He turned heads in 2016 for being the only prominent election prognosticator to predict that Donald Trump would win, based on a formula he’d used since 1984 built around the popularity of the incumbent party. The next year, he published a book predicting Trump’s impeachment.4

I would imagine that to most suburban white people who drive to their jobs and thus have valid driver’s licenses, the demand that voters get a license or some other kind of ID doesn’t sound especially onerous. But we often forget that one needs documents to get documents. To secure a driver’s license in most states, a person needs to show a birth certificate and proof of residence, and perhaps a Social Security card. In the case of people who move frequently—young people, college students, poor people, all of whom lean Democratic—the addresses on these cards may not match. Older African-Americans born under Jim Crow may not even have been issued birth certificates.5

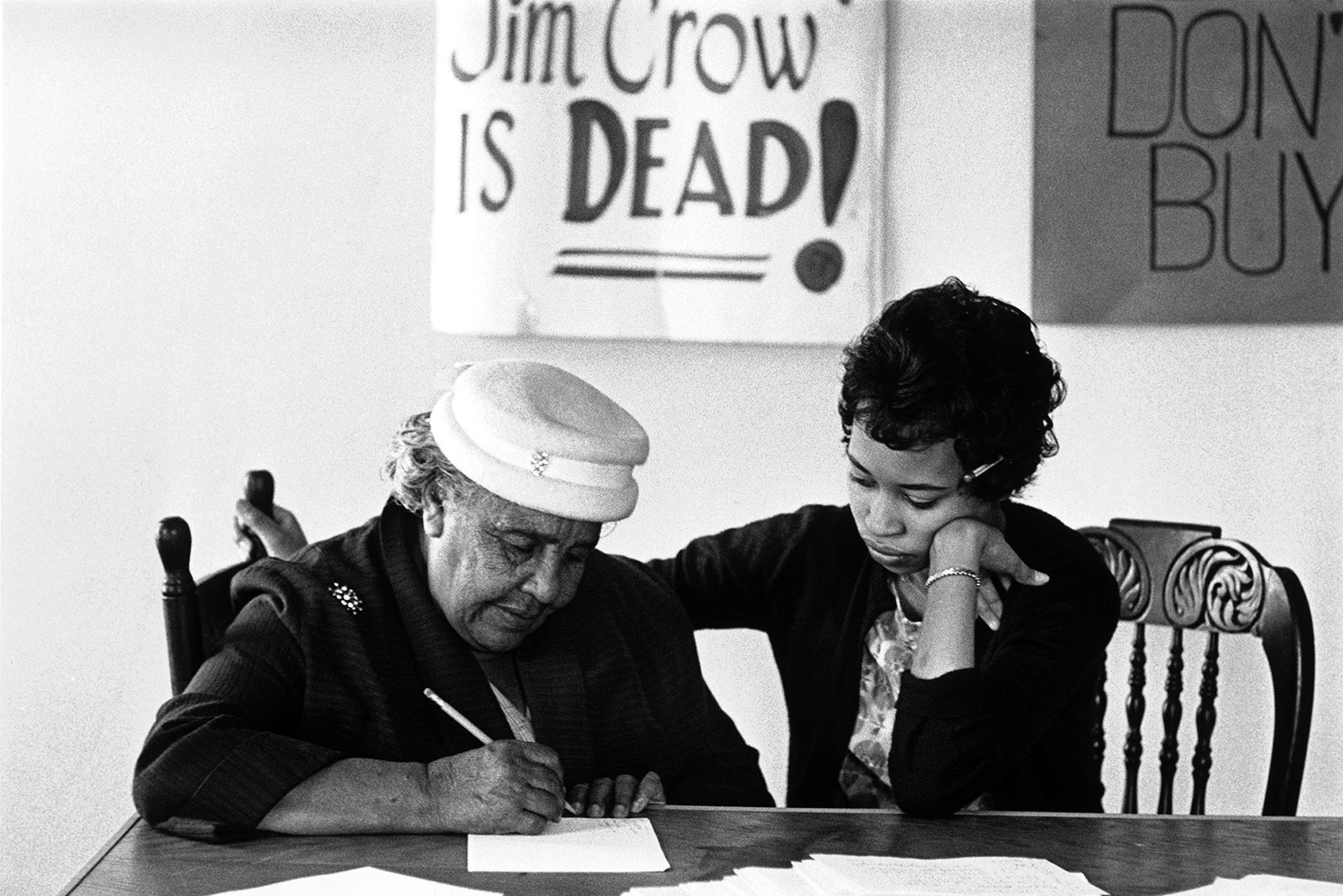

Lichtman draws attention, as some journalists have, to the case of Rosanell Eaton, who grew up in North Carolina in the Jim Crow era and joined an NAACP lawsuit against VIVA as a plaintiff. In a book that is mostly a straightforward history-from-above narrative, Eaton’s story provides one of the more gripping passages:

In 1942, Eaton rode for two miles on a mule-drawn wagon to register to vote at the Franklin County courthouse. Three white male officials confronted her. They ordered her to stand up straight, keep her arms at her side, and recite from memory the preamble to the Constitution. She did so word for word and then passed a written literacy test, becoming one of the few African Americans of her era to vote in North Carolina.

Seven decades later, Lichtman writes, “Eaton had a much harder time qualifying to vote under North Carolina’s new law.” She had a driver’s license, but the names on her license and her voter-registration card did not match exactly. She made eleven trips to the Department of Motor Vehicles, two different Social Security offices, and three banks before everything was rectified. “I was hoping I would be dead before I’d have to see all this again,” she said.

Advertisement

In 2016 the Fourth Circuit Court of Appeals struck down VIVA. The court’s ruling charged that the state’s Republicans “target[ed] African Americans with almost surgical precision.” So that effort at voter suppression is off the books. The district lines that Republicans drew in 2011, meanwhile, the ones that gave the GOP an overwhelming majority in the state’s congressional delegation, are still in effect and are the subject of court battles. The Supreme Court may hear a case challenging them next spring.

The great value of Lichtman’s book is the way it puts today’s right-wing voter suppression efforts in their historical setting. He identifies the current push as the third crackdown on African-American voting rights in our history.

The first came in the early days of the republic. In some state constitutions that dated to independence, Lichtman notes, some blacks, usually those few who met certain property qualifications, were granted suffrage. But protests were often immediate when they did vote. In 1803 in Wallingford, Connecticut, losers of a local election complained that “a Negro fellow by the name of Toby” had been allowed to vote for the winners. This affront was compounded, they alleged, because this “Black night walker” had once attempted to rape a white woman. By 1814, the state legally limited the franchise to whites.

And so it went. In Maryland, the original state constitution of 1776 actually allowed property-owning African-Americans to vote. Then their numbers increased, and by 1802, the legislature banned them from voting. New Jersey followed a similar arc, allowing blacks to vote under its original constitution but ending the practice in 1807. In New York, some blacks could vote under the 1777 constitution. A rewriting in 1821 stopped just short of explicitly limiting the vote to whites, but it imposed a property qualification “which we know they cannot comply with,” as one delegate put it.

The second crackdown came after Reconstruction, which ended in 1877. During Reconstruction, blacks in the South gained full citizenship rights, which were enforced by occupying Union soldiers. But even then, the national will to safeguard those rights was scant. In 1875 President Ulysses Grant and some of his fellow Republicans—the good guys, at that time—sought to pass a bill to “redeem” the words of the Fifteenth Amendment, which granted the franchise to persons previously held as slaves, by legislating meaningful enforcement provisions. Joseph Gurney Cannon, a leading Republican congressman of the day for whom one of the three House office buildings along Independence Avenue is named, argued, “Will we protect these men [African-Americans] or will we leave them to be overborne and butchered?” The House passed the bill, but the Senate didn’t act on it. Even in Lincoln’s party, opinion was divided on how far they were willing to go to protect and defend black people’s rights.

Once the Union troops left the South, African-Americans’ rights were stripped by means both legal and violent. The violent means—the rise of the Ku Klux Klan—everyone knows about. Somewhat less well known are the legal efforts—the state constitutions passed by southern states that explicitly enshrined white supremacism in law. “There is no use to equivocate or lie about the matter,” said the Mississippian James Vardaman of that state’s 1890 constitution. “Mississippi’s constitutional convention of 1890 was held for no other purpose than to eliminate the nigger from politics.”6

That was led by the Democratic Party, which was then a white supremacist party (in the South; in the North, it was the party of immigrants). But, as Lichtman writes, it’s not as if the Republicans fought for blacks. After Reconstruction, they ended their efforts in the South, leaving the region and its people to the Jim Crow Democrats. Those African-Americans who could vote were loyal Republican voters for obvious reasons, but over the course of the early twentieth century that loyalty waned. From 1896 to 1932, Republicans controlled the White House for all but eight years, and Congress for much of that time; yet, writes Lichtman, they could never rouse themselves to pass an anti-lynching law. The National Colored Republican Conference complained in 1924, “In the party’s willingness to be fair, many have no confidence, and a change is imperative.” Four years later, when Herbert Hoover proved more tone-deaf than usual on race and civil rights, African-Americans were already prepared to bolt the party for Franklin Roosevelt—belying the idea that the Depression prompted them to switch sides.

As awfully as blacks were treated, the white men who ran the country took their plight more seriously than they did that of women. The Fourteenth Amendment, which guaranteed the right to citizenship for blacks, also said, in Section 2, “But when the right to vote at any election…is denied to any of the male inhabitants of such State…” It was the first insertion of the word “male” into the Constitution, as Lichtman notes, and it happened over the clear objections of the great women’s leaders of the day. Susan B. Anthony demanded that Republicans “hold the party to a logical consistency that shall give every responsible citizen in every State equal right to the ballot,” but even the most progressive-minded male leaders argued that they could pass legislation enforcing voting rights for blacks, but if they included women’s suffrage, it would fail. “I know that the time will come,” said Ohio senator Benjamin Wade, one of the most radical of the Radical Republicans. “Not today, but the time is approaching.” Women would hear this for another six decades, and they continue to hear it in different forms today.

Still, at least when women finally did win suffrage, the right was largely recognized. This was never so for African-Americans. Nothing that Republicans are doing today is new. In the early days of the republic, Lichtman writes, members of Alexander Hamilton’s Federalist Party raised regular allegations of voter fraud and sought to require men to bring to the polls proof of their property qualifications. As for “ballot security,” as the Republicans sometimes call their efforts, the GOP rolled out “Operation Eagle Eye” back in 1964, the first modern election in which the party sought to appeal to the racist vote. Eagle Eye targeted heavily Democratic, mostly minority precincts in thirty-six cities. It was based on a program that had already been tried in Arizona, which involved voter intimidation, the circulation of handbills warning that if you had outstanding parking tickets you couldn’t vote—the usual tricks. It didn’t work, but no one was ever known to have been caught and prosecuted or punished for it in any way. One of the participants in the Arizona program, William Rehnquist, was “punished” a quarter-century later by being confirmed as the sixteenth chief justice of the Supreme Court.

Today, as we approach November and a highly anticipated anti-Trump wave at the polls, Republicans in jurisdictions they control are getting more and more brazen in their voter-suppression efforts. The most darkly comic attempt emanated from Georgia, where election officials sought to close seven out of nine polling places in one predominantly African-American county because they weren’t compliant with the Americans with Disabilities Act. Citizens protested. County officials at first insisted that they absolutely had only the county’s disabled voters in mind, until a national outcry forced them to reverse course.7

In North Carolina, the stakes are unusually high. The state legislature, Michael Li of the Brennan Center for Justice told me, will be elected according to new district maps, the old ones having been tossed out by a court because of racial gerrymandering. It’s unlikely the Democrats can win enough seats to capture a majority, but they can win enough to end the Republican supermajority, which would mean the legislature could no longer override vetoes by Democratic governor Roy Cooper.

The congressional elections, however, will still be based on the districts the Republicans drew seven years ago. On August 27, a panel of three federal judges in the state found those districts to be unconstitutional due to partisan gerrymandering, but it also said that it was too late to draw new ones by November 6. Nevertheless, depending on the strength of Democratic turnout, the party could gain as many as three House seats there.

Voting-rights advocates had hoped that the Supreme Court would hear the challenge to the North Carolina districting while Anthony Kennedy was still on the bench, which could have given them a fighting chance at a decision that would ban partisan gerrymandering. A victory in that case would have had thunderous ramifications. The Court may still hear it, but with Kavanaugh now filling Kennedy’s seat, the already slim hope of success would seem to be nonexistent.

Beyond 2018, Democrats, liberal nonprofits, foundations, and donors simply must be more focused on these issues and put more resources into fighting Republicans. There should be a broad push, for example, for amending the Constitution to include a basic federal right to vote. Some people are surprised to learn this isn’t in the Constitution, but it is the sort of thing the founders left to the states. A federal right would make all these state voter-suppression laws eminently more challengeable.

Right now, however, the general posture of these groups is that they don’t want to tinker with the Constitution; doing that is “their” issue (i.e., the right’s). This is astonishingly shortsighted. One day, given the way polarization is testing the limits of our system of checks and balances, a public consensus might well emerge acknowledging that some changes to the Constitution are needed. The right has its list; it is topped by a federal balanced budget amendment, which would decimate domestic spending or entitlements or both. Is the left just to remain silent when the time for that debate arrives?

If the current third wave of voter-suppression techniques is halted, history suggests that there will be a fourth and a fifth. Today’s Republican Party is not simply trying to win elections. It is simultaneously trying to rewrite the rules—gerrymandering and voter suppression are crucial to this effort—so that it never loses a federal election again. Too many liberals can’t bring themselves to acknowledge this. I hope that on this issue, as has happened on some others, the age of Trump will finally cause the scales to fall from their eyes.

—October 11, 2018

This Issue

November 8, 2018

MLK: What We Lost

The Concrete Jungle

‘Inventing New Ways to Be’

-

1

See Michael Wines, “Wisconsin Strict ID Law Discouraged Voters, Study Finds,” The New York Times, September 25, 2017. ↩

-

2

See my “Ratfucked Again,” The New York Review, June 7, 2018. ↩

-

3

See Justin Levitt, “A Comprehensive Investigation of Voter Impersonation Finds 31 Credible Incidents Out of One Billion Votes Cast,” The Washington Post, August 6, 2014. ↩

-

4

The Case for Impeachment (William Morrow/Dey Street, 2017); reviewed in these pages by Noah Feldman and Jacob Weisberg, September 28, 2017. ↩

-

5

For a discussion of these complications, see Barrett Holmes Pitner, “The Best Way to Fight Voter-ID Laws? Give Voters IDs!,” The Daily Beast, August 28, 2018. ↩

-

6

See Neil R. McMillen, Dark Journey: Black Mississippians in the Age of Jim Crow (University of Illinois Press, 1989), p. 43. ↩

-

7

See Dana Milbank, “The GOP Turns to Toilets to Suppress More Black Voters,” The Washington Post, August 21, 2018. ↩