The late American poet Bill Knott, who used to teach a class on poetic forms at Emerson College in Boston, knew an exercise, or perhaps you could call it a trick, by which you could turn any poem into a sonnet. Choose a poem (your own or someone else’s) of about one hundred words, then locate all the rhyming words and write them in a column. You’ll find that any unrhymed poem (take “Leaving the Atocha Station,” by John Ashbery) is likely to contain some rhymes (bats/rats, scarecrow/window) and slant rhymes (prayer/hair, amnesiac/enthusiastic). Next, try to arrange the pairs into the rhyme scheme of either a Petrarchan or an Elizabethan sonnet, and rewrite and reorder the lines accordingly, using synonyms as necessary to fill in the missing rhymes. Finally, nudge the syllabics, so that the lines are about ten syllables each—extra points if you can make the feet iambic. You’ve created a sonnet, or something like it.

For the student of poetry, this bit of magic is doubly instructive. It both illustrates the mutability of drafts and demystifies the craft of form; a writer needn’t think in rhyme and meter in order to produce a formal poem. If you make a habit of writing in form, however, you may begin to think in form. In How Music Works (2012), David Byrne explains that pop songs are typically three to five minutes long because that’s how much music fit on one side of a 78. It still feels like the right length for a pop song. Shakespeare probably started to think in 140-syllable bursts, the way a photographer I heard about began to think in Instagram captions—his mind automatically described the world in chunks of text of about 2,200 characters. This is habit via repetition; doing something over and over again changes your brain. That’s why Knott instructed his students to stick to one form for a while. Otherwise, he’d scold, “you’re not learning anything.”

In her fourth collection, Like, A.E. Stallings, an American poet, classicist, and translator who lives in Greece, demonstrates facility with poetic forms of all types. Like includes examples of the villanelle, the epigram, the sestina, ottava rima, and, of course, the sonnet, of which there are several, some taking more liberties than others. Even the table of contents is arranged alphabetically, to suggest an abecedarian of titles—a bonus poem. This display of range will feel to some readers like virtuosic versatility; to Knottier readers the frequent costume changes might look jumpy or noncommittal.

Stallings may be so immersed in form that her thoughts arrive already dressed in it—or maybe they arrive formless, but she so enjoys the game of arranging those thoughts into patterns of meter and rhyme that almost any occasion will do. She moves freely between the mythic and the quotidian, between epic and modest scales—one poem, “Lost and Found,” begins with a search for a misplaced fragment of toy (“Some vital Lego brick or puzzle piece”) and ends up traveling to a Valley of Lost Things set not in Oz but on the moon. Others remain firmly domestic; the muse might arrive while the speaker reseasons a cast-iron skillet (as in “Cast Irony”) or picks lice or glitter (two separate poems, “Lice” and “Glitter”) from a daughter’s hair.

These more humble poems sometimes allude to graver problems: “now it’s personal, it’s/chemical, it’s war,” she writes in “Lice”; “Mankind will never/be rid of them; like the poor/they’re always with us.” But in the poem’s final line she admits the pests are “harmless,” embarrassing but not dangerous. In this very socially conscious time, such references might betray an authorial worry: Are these poems relevant enough?

The poems depicting a home and a family life that seems enviably loving often contain an undercurrent of anxiety. As Robert Burton advises in The Anatomy of Melancholy, Sperate miseri, cavete felices—“Hope, ye unhappy ones; ye happy ones, fear.” In “Empathy,” Stallings writes, “My love, I’m grateful tonight/Our listing bed isn’t a raft/Precariously adrift/As we dodge the coast guard light.” Grateful too that her children are safe in their bunks, unlike the drowned refugees for whom she writes a “proposed epitaph” later in the book. It’s part of a poem that also contains an appendix of “useful phrases in Arabic, Farsi/Dari, and Greek,” found in a volunteering guide—poems within poems. This “Refugee Fugue” deals directly with an ongoing humanitarian crisis, but of course signposted “relevance” is not the only way for poems to be political.

Like also includes prose poems, and they too can feel like sonnets. Take “The Concubines,” one section of the five-part “Battle of Plataea: Aftermath,” based on the Histories of Herodotus. This block of prose seems ready-made for sonnet transformation, 116 words long and full of rhymes both exact and slant:

Advertisement

We heard the Greeks had won. At once I went and decked myself with every bracelet, ring, gold necklace that I owned, and rouged my cheeks, and hastily had my maids arrange my hair. The other concubines slumped in despair; but I’d been snatched from Kos; my people, Greeks! Dressed in white robes of silk, we fled the tent, and drove through corpses, far as the eye could see, until I saw Pausanius, the king. I stepped with golden sandals through the gore, the lady that I was, and not the whore, and knelt, a supplicant, Please set me free. The roar of blood like silence in my ear, until: “Lady, arise, be of good cheer.”

The rhymes pop right out: Hair/despair. Gore/whore. And the first ten syllables are perfectly iambic: “We heard the Greeks had won. At once I went.” The poem even ends with a rhymed couplet, or what would be a couplet if the poem were broken up into lines. It reads as though Stallings had done Bill Knott’s exercise in reverse, writing a sonnet first and then deconstructing it to obscure the underlying form.

Most of Stallings’s poems have end rhymes, but she works in free verse too, and these more unpredictable poems are among my favorites; because the book teaches me to expect a form, I search for one and am pleasantly denied. The inclusion of a free verse poem in a book so formal also encourages us to think of free verse as another available form, the way we can think of literary fiction as a “genre” with its own conventions. The rule in this case may be no set rules, but “Art Monster,” a poem in tercets and relatively short lines, is in a tradition with Sylvia Plath through its shape on the page alone—I automatically think of Ariel. Stallings must count her as an influence; Plath was also very formally inclined, and Stallings in her poems uses certain signature Plath words like “denouement” and “fathom” (as in “Full Fathom Five”) and “jilt” (two of the poems in the “Juvenilia” section of Plath’s Collected Poems include the word “jilted”), as well as words that just seem Plath-y even if Plath never used them, like “pulchritude.”

“Art Monster” is a reference to Jenny Offill’s 2014 novel Dept. of Speculation, in which the narrator proclaims:

My plan was to never get married. I was going to be an art monster instead. Women almost never become art monsters because art monsters only concern themselves with art, never mundane things. Nabokov didn’t even fold his own umbrella. Vera licked his stamps for him.

The phrase “art monster” gestures toward complicated gender and class politics, suggesting the privilege inherent in having the time to write or be creative. You could use it as an insult or an accusation, in particular if you’re talking about a man, but as with reclaimed slurs like witch or slut, some women find the epithet appealing; they yearn to be as self-important and demanding and protective of their time as men.

Stallings’s “art monster” is the Minotaur, and the poem is told through his voice: “My mother fell for beauty,/Although it was another species,/Ox-eyed, dew-lapped, groomed for sacrifice.” Many of Stallings’s rhyming poems begin this strongly, with a striking opening; what follows can feel more perfunctory, fulfilling the set expectations. But “Art Monster” remains engaged with itself throughout, as though it needed to justify its lack of regular formal properties with extra sonic surprises and linguistic inventiveness in every line (see “De-monster the darkness,” which suggests “demonstrate the darkness”: removing the demon would create a black hole to make blackness even blacker). Like Plath’s “Daddy,” this is a poem that contends with the burden of parental influence, and it’s also Plath-like in its macabre playfulness (“my hirsute//hair shirt” reminds me very much of “you do not do/Any more, black shoe”). “It is heroic to slay,” Stallings writes, recalling Plath’s “Daddy, I have had to kill you” and “If I’ve killed one man, I’ve killed two” (both her father and husband, perhaps).

But what makes the Minotaur an art monster, specifically, is that he’s a writer: “I bow to the yoke/of making, scratching this earliest of inscriptions//On a potsherd, down here in the midden.” (A “potsherd” is a shard of pottery, but I kept wanting to read it as “postcard,” a message mailed from the labyrinth.) Here Stallings identifies with the Minotaur the way Offill identifies with Nabokov, as a creature more selfish than selfless, one who must compulsively create whatever the cost: “Writing left to right…as a broken beast furrows a field.” That cost may be part of the source of Stallings’s anxiety, an anxiety of privilege. She may be grateful that her children don’t face the struggles of refugees, but she feels guilty about it too: “Empathy isn’t generous,/It’s selfish.” That is to say, other people’s pain is painful insofar as we imagine it could be our own.

Advertisement

In a recent thread about sonnets on Twitter, the poet and critic Dana Levin remarked that traditional forms “have resurged.” She added, “Why is that? Is it the way it can hold all our screaming?” When we feel helpless, do metrical forms offer the illusion of control? Or are we drawn to tradition itself, because it’s familiar, and therefore comforting? The New Formalists of the 1980s and 1990s were a school of reaction, but they seemed to be reacting to what you might call anti-establishment trends in poetry, not social unrest. In the preface to their anthology Rebel Angels (1996), Mark Jarman and David Mason wrote:

It is no surprise that the most significant development in recent American poetry has been a resurgence of meter and rhyme, as well as narrative, among large numbers of young poets, after a period when these essential elements of verse had been suppressed.

Suppressed sounds a little beleaguered, as though powerful bodies were censoring formal poems, when they’d just gotten less popular for a while. The current vogue for narrative in particular feels different; there’s a sense that formal innovation would be a distraction from the undertold or actively suppressed stories we’re almost starved for.

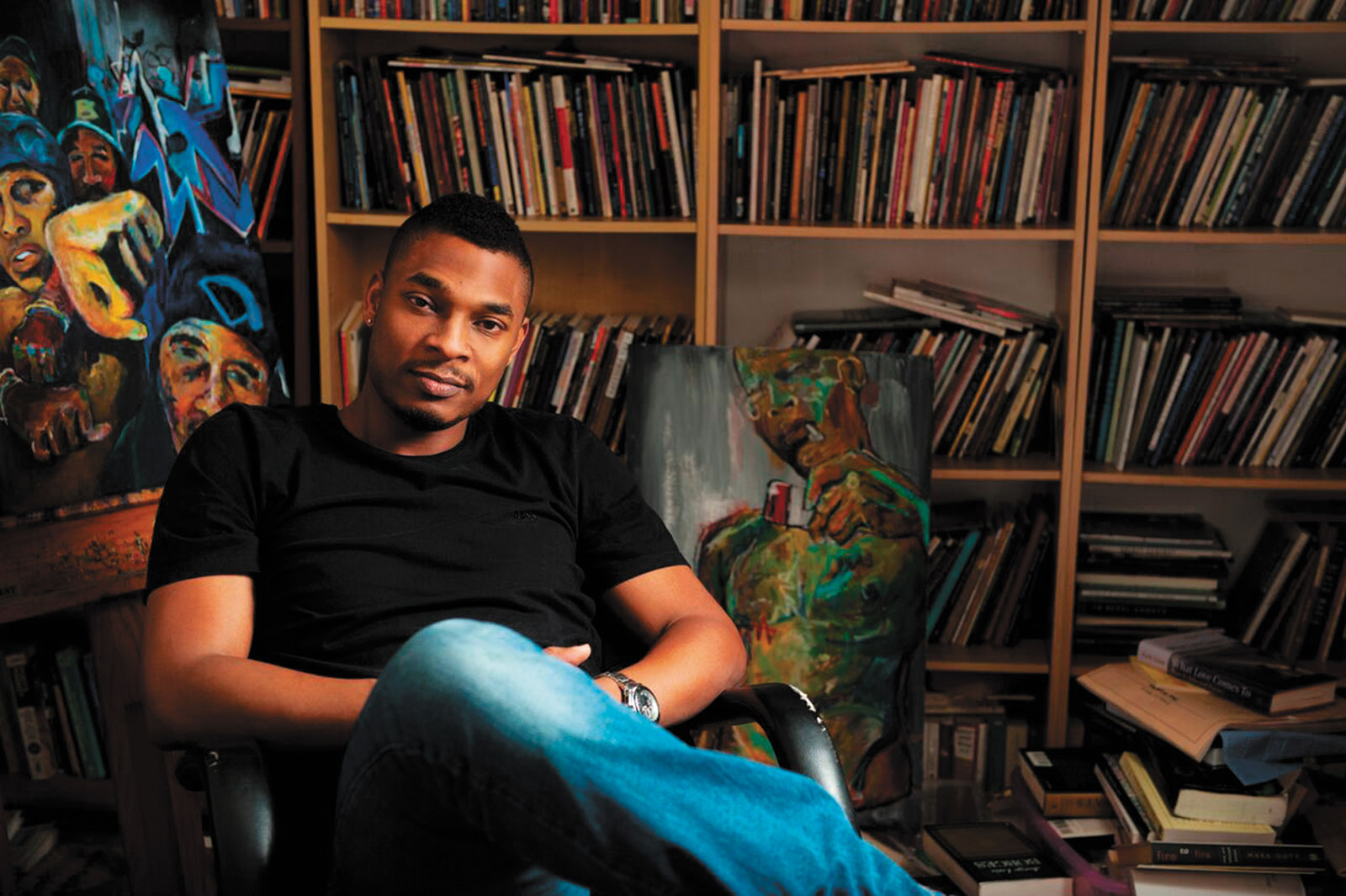

There can be no question as to the timeliness of American Sonnets for My Past and Future Assassin, Terrance Hayes’s seventh book—it’s a collection of poems written during the first two hundred days of Donald Trump’s presidency. There’s a countertradition of arbitrarily calling any poem a sonnet—“XXXVI” from Ted Berrigan’s The Sonnets, for example, is twenty lines long—but every poem in this book, in addition to carrying the same title, “American Sonnet for My Past and Future Assassin,” is recognizably a sonnet. They do not all follow a typical rhyme scheme, but some do, and several end with the classical Elizabethan rhyming couplet: “I love how your blackness leaves them in the dark./I love how even your sound-bite leaves a mark.” Another, more slant: “It’s not the bad people who are brave/I fear, it’s the good people who are afraid.”

Hayes borrows the concept of the American sonnet from the influential California poet Wanda Coleman, who supplies the book’s epigraph (“bring me/to where/my blood runs”). Coleman, who died in 2013, published most of her books with the independent, avant-garde-leaning Black Sparrow Press, dealt with racism and poverty explicitly in her work, and took a “jazz” approach to traditional form with sonnets that involved, in her words, “progression, improvisation, mimicry.” In an interview with Paul E. Nelson, quoted on Hayes’s acknowledgments page, she said, “I decided to have fun.” And they are fun—“a mystic gone ballistic, not home but blood/on the range” she writes in “American Sonnets: 91.” Hayes too seems to be having fun, treating the writing, almost like Stallings, as a kind of play, although his subject matter is frequently devastating.

If Stallings’s combination of cultural influences is American and classical Greek, Hayes’s could be the poetics of whiteness and of blackness, which arrive in conflict in the lines that open the book:

The black poet would love to say

his century began

With Hughes or God forbid,

Wheatley, but actually

It began with all the poetry

weirdos & worriers, warriors,

Poetry whiners & winos falling

from ship bows, sunset

Bridges & windows.

Hayes might be suggesting that his first exposure to verse was not to black verse, not to Langston Hughes or Phillis Wheatley, a slave and the first black poet to publish a book in America, but to the white canon of the twentieth century—those suicidal, alcoholic “whiners & winos” like Hart Crane (who jumped off a boat; in an impossible irony, his father invented the Life Saver, not the flotation device but the candy) and John Berryman (who jumped off a bridge). Or he might be saying—I’m honestly not sure—that he, to his own regret, was reading the white poets instead by choice.

How should we read that “God forbid”? Wheatley’s writing betrays some internalized racism; her poem “On Being Brought from Africa to America” begins “’Twas mercy brought me from my Pagan land,/Taught my benighted soul to understand/That there’s a God.” Perhaps “God forbid” is ironic projection, a challenge to the anticipated “performatively woke” reader. Hayes’s use of form feels almost ironic, a way of turning the canon back on itself. (In Lucinella, Lore Segal’s satirical novella about Yaddo, the black poet Newman proclaims, “Technique is racist.”)

Hayes’s poem goes on: “In a second I’ll tell you how little/Writing rescues.” (So much for the lifesaver.) “My hunch is that Sylvia Plath was not/Especially fun company.” This line accomplishes a lot: it’s a pretty good jab (“I decided to have fun”) but also sets up an uneasy tension in the comparison of Wheatley, a literal slave, to Plath, whom we tend to think of as a victim—the victim of misogyny at large and more locally of a cruel and manipulative spouse. It also retroactively makes that “Hughes” reference ambiguous; now Ted is in the room too!

After seeming to insult her (“A drama queen, thin-skinned,/And skittery”), Hayes then comes to Plath’s defense: “she thought her poems were ordinary./What do you call a visionary who does not recognize/Her vision?” As a volta—the sonnet’s traditional reversal or swerve—this is truly surprising and a little thrilling. It seems absurd to call Plath underrated, but I do, all the same, think she’s underrated. There’s so much focus on her persona, on the cult of Plath, that it’s easy to forget that her poetry is brilliant—I hope in my lifetime to write five words in a row as good as “I eat men like air.”

If you are a white person reading this, do not get too comfortable; we don’t all get off as easy as Plath. This book is both largely about and addressed to the white supremacist systems in America that historically supported slavery and now disenfranchise black voters and allow cops to kill black people with impunity. The murderers of Hayes’s ancestors, whoever might murder him or his family—how are these poems for them? They are not written in dedication—they are more like an education (see, for example, a sonnet that explains the contours of James Baldwin’s face) and a plea (for attention, surrender, kindness, mercy, shared fury). Hayes writes:

Something happened

In Sanford, something

happened in Ferguson

And Brooklyn & Charleston,

something happened

In Chicago & Cleveland &

Baltimore & happens

Almost everywhere in this country

every day.

That sarcastically vague “something” that just “happens” is the ultimate euphemism for state-sanctioned murder, which every black man is taught to fear and even expect: “The names alive are like the names/In graves.” Some poems address Trump directly: “Are you not the color of this country’s current threat/Advisory?” They try to operate as weapons or traps: “I lock you in an American sonnet that is part prison,/Part panic closet, a little room in a house set aflame.” (Sonnets are often compared to boxes; stanza is Italian for room.) But they are aware of their own futility: “It is not enough/To love you. It is not enough to want you destroyed.” Should we come together? Burn everything to the ground? Both love and hate fail as strategies.

The idea of complicity runs through the book like a leitmotif. One sonnet notes: “Even the most kindhearted white woman…may begin, almost/Carelessly, to breathe n-words…When she drives alone…before she can catch herself.” Nothing is harmless, Hayes suggests: “Of course,/After that, what is inward, is absorbed.” Reading this as a white woman, I wonder if I’ve done that myself. Then, two pages later, there’s a poem that contains the n-word several times over (albeit with a slightly more acceptable spelling variation), and I am forced to say it, if only in the silence of my own head; in America, I’m reminded, participating in evil is unavoidable. (Hayes hates to hear himself say it, too; a poem later in the book declares, “Nothing saddens me more.”)

One of the most damning sonnets uses litany and anaphora to great effect, each accusatory line beginning with “You don’t seem”:

You don’t seem to want it, but you

wanted it.

You don’t seem to want it, but you

won’t admit it.

You don’t seem to want admittance.

You don’t seem to want admission.

You don’t seem to want it, but you

haunt it.

You don’t seem too haunted, but

you haunted.

The precise meaning of these lines changes depending on who we imagine the poem is addressing—Trump? Any American? The poet himself?—but the general meaning is clear: it’s about complicity and denial. The turn comes, as in Shakespeare’s sonnets, just before the last couplet, when Hayes suddenly introduces African-American vernacular English in the twelfth line: “You don’t seem to pray but you full of prayers.” This has an astonishing effect on the last line, which is identical, verbatim, to the sixth line, as above. Here’s the full final couplet: “You don’t seem to want it, but you wanted it./You don’t seem too haunted, but you haunted.” The first time we read the line, we understand “haunted” as a verb in the past tense: You did haunt, you have haunted. The second time we read the line, we understand “haunted” as an adjective, a past participle: You are haunted. This reversal adds a new shade of meaning that deepens and darkens the poem. It’s like looking at the negative of a photograph, how the faces grown uncanny and skull-like.

In that first poem, full of the ghosts of American poetry’s past, Hayes tells us that “Orpheus was alone when he invented writing.” The poem that begins the book’s second section brings in another white (and onanistic) ghost: “We suppose Ms. Dickinson is like the abandoned/Lover of Orpheus & too, that she loved to masturbate/Whispering lonely dark blue lullabies to Death.” Dickinson, like Plath, is often read through a biographical lens—as a jilted lover and a woman denied due fame in her own time. She—Emily—wrote in the poem usually numbered 341, “After great pain, a formal feeling comes.”

I thought of this line while reading these books. For many Americans, it’s been a time of great pain. For others, the idea that life has gotten suddenly worse since the 2016 election is laughable. Perhaps certain kinds of pain have just become more visible. “We’re here for the time being,” Stallings writes in Like’s first poem, presumably referring to Athens, and then, paraphrasing a Greek proverb: “Nothing is more permanent than the temporary.” Hayes writes, “This country is mine as much as an orphan’s house is his.” He could mean both America and the sonnet. Stuck in temporary, haunted, inhospitable housing, you might decide to have fun, to inhabit it as fully as possible for as long as you’re there.

This Issue

December 6, 2018

Saboteur in Chief

Opioid Nation