It is hard to give up something you claim you never had. That is the difficulty Americans face with respect to their country’s empire. Since the era of Theodore Roosevelt, politicians, journalists, and even some historians have deployed euphemisms—“expansionism,” “the large policy,” “internationalism,” “global leadership”—to disguise America’s imperial ambitions. According to the exceptionalist creed embraced by both political parties and most of the press, imperialism was a European venture that involved seizing territories, extracting their resources, and dominating their (invariably dark-skinned) populations. Americans, we have been told, do things differently: they bestow self-determination on backward peoples who yearn for it. The refusal to acknowledge that Americans have pursued their own version of empire—with the same self-deceiving hubris as Europeans—makes it hard to see that the US empire might (like the others) have a limited lifespan. All empires eventually end, but maybe an exceptional force for global good could last forever—or so its champions seem to believe.

The refusal to contemplate the scaling back of empire shuts down what ought to be our most urgent foreign policy debate before it has even begun. That is why these two new books are so necessary, and so welcome: they are the most serious efforts since Chalmers Johnson’s Blowback series (2004–2010) to reopen the question of American empire by taking for granted that it exists. Victor Bulmer-Thomas’s Empire in Retreat maintains that America has harbored imperial ambitions since its founding, and argues that its focus shifted in the twentieth century, from acquiring territory to penetrating foreign countries and influencing their governments to support US strategic and economic interests. David Hendrickson’s Republic in Peril sees that shift as the result of a decisive embrace of interventionism, aimed at extending US power throughout the world.

Both authors think withdrawal from overextended military commitments could strengthen America. Bulmer-Thomas, a British diplomat and scholar, recommends it as a pragmatic adjustment to shrinking support for US empire at home and abroad. Hendrickson, a political scientist at Colorado College, provides a theoretical rationale for it, exploring the possibility of what he calls a new internationalism, based on respect for the sovereignty of other nations. Yet even as they catalog the many signs of imperial decline (economic, political, cultural), neither is sanguine that American policymakers can manage a graceful retreat.

Bulmer-Thomas begins by recounting the rise of the US territorial empire. He shows that America’s relationship with the land it acquired during westward expansion resembled the relationship between European countries and their colonies abroad. The United States, like European colonial powers, subjugated (and nearly exterminated) aboriginal populations; used military occupation as a buffer between white settlers and rebellious natives; and established only limited representative governments in their occupied territories. One resident of America’s territories complained that they were treated like “mere colonies, occupying much the same relation to the General Government as the colonies did to the British government prior to the Revolution.”

Most textbooks date the beginning of America’s overseas expansion to 1898, when it acquired sovereignty over Cuba, Guam, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines after the conclusion of its war with Spain. Yet as Bulmer-Thomas shows, the US empire went offshore much earlier. During the 1810s and 1820s, Americans carved out the state of Liberia in West Africa, allegedly as a refuge for free American blacks; the country in fact functioned as an American colony and later as a protectorate of the Firestone Rubber Company. The US established an imperial presence in East Asia as early as 1844, when the Treaty of Wanghia gave it the same privileged access to Chinese ports as the British Empire, and went on to acquire dozens of “guano islands” in the Pacific, where abundant bird droppings provided a rich source of fertilizer.

During the 1890s, the American zeal for distant acquisitions slipped into high gear, as politicians realized they were arriving late to the imperial game. Led by Theodore Roosevelt and other advocates of expansion, they sought land through annexation and collaboration with American business interests (Hawaii) as well as through war with Spain. These acquisitions began as additions to the territorial empire but gradually acquired a more ambiguous character. They came to form the foundation of what Bulmer-Thomas calls America’s “semi-global empire,” built not on territorial acquisition but on the maintenance of client states and various other forms of international interference, including military bases that supported occasional armed interventions in local conflicts and multinational corporations run mostly by Americans.

The Philippines offers a case in point of America’s nonterritorial form of empire. The US declared war on Spain in 1898 with the avowed intention of ending Spanish rule in Cuba, but even before the declaration President William McKinley had dispatched the US Asiatic Squadron under Commodore George Dewey to Hong Kong in preparation for an assault on the Spanish fleet in Manila Bay. As soon as war was declared, Dewey moved quickly and crushed the Spanish forces. Their surrender emboldened the Filipino rebels, who erroneously assumed that the US had arrived to liberate them from their Spanish oppressors. The US military quickly disabused them of that delusion by embarking on a ferocious counterinsurgency campaign, which lasted for years and included the systematic torture and slaughter of Filipinos. As many as 250,000 died, but the US imperialists never doubted the sanctity of their cause. “Nothing can be more preposterous than the proposition that these men were entitled to receive from us sovereignty over the entire country which we were invading,” Secretary of War Elihu Root said in 1900 about the Filipino rebels. “As well the friendly Indians, who have helped us in our Indian wars, might have claimed the sovereignty of the West.”

Advertisement

Statehood was never considered during the debate over the Philippines: the only question was whether to establish a naval base at Manila and give the islands back to the Spanish or to annex the entire archipelago. The imperialists won the argument, and after the insurgents were finally suppressed the Philippines became a colony, from which investors in sugar, hemp, tobacco, and coconut oil could gain privileged access to US markets and Filipinos could emigrate to America in search of jobs. By the 1930s, congressional opposition to cheap exports as well as to cheap (and nonwhite) labor created support for Philippine independence, which was finally achieved in 1946. But it came with so many restrictions on trade and so much preferential treatment for American investors—not to mention continued maintenance of US military bases—that “it would be more accurate to describe the Philippines as becoming a US protectorate,” Bulmer-Thomas writes. “Thus, the end of colonialism in the Philippines did not mean the end of US imperial control.”

A similar pattern of indirect imperial control also applied to Central America and the Caribbean. The US dominated that region during the twentieth century through colonies (Puerto Rico, the Virgin Islands, the Panama Canal Zone), but more broadly by using its economic influence to interfere in domestic politics and maintain governments that would faithfully serve American interests (as was the case in Cuba until 1959), or by establishing asymmetrical bilateral treaties and customs receiverships—the collection of customs duties by US officials, who then used the money to pay off the debt service owed on American loans. This arrangement survived in the Dominican Republic until 1942 and in Haiti until 1947.

Military interventions underwrote economic domination. Sometimes this involved sending in the US Marines and leaving them in place for decades, as in Haiti from 1915 to 1934. Sometimes it required using military force to crush a rebellion and arranging for the emergence of a cooperative dictator, such as Rafael Trujillo in the Dominican Republic, whose brutalities the Americans tolerated as long as he respected US strategic interests in the region. This he did for thirty years, until his attempt in 1960 to overthrow the Venezuelan government cost him US support. Sensing an opportunity, his opponents assassinated him. But the US was still committed to maintaining the imperial relationship, and President Lyndon Johnson sent in the Marines in 1965 to prevent the left-of-center president Juan Bosch (who had been ousted by a military coup) from returning to power.

Johnson’s intervention recalled the conflicts of the early twentieth century, but during World War II and the cold war, US imperial strategies had begun to shift. As the USSR consolidated its power, the US scaled back its pursuit of territory abroad. Instead, it extended its imperial reach through the development of international institutions that would serve its interests but could not also be used against it. At Bretton Woods in 1944, the US initiated the creation of the IMF and the World Bank. Both institutions are headquartered in Washington, and the president of the World Bank has always been an American, by custom if not fiat.

The Point Four Program, drawn from Harry Truman’s inaugural address in 1949, linked the World Bank to the struggle with the Soviet Union for influence in the developing world, where the bank would make loans, with many political conditions attached, to governments and state-owned enterprises (later privately owned ones as well). The requirement that Congress approve these loans ensured that they would reflect what the US government considered its national interest. The United Nations, too, began as an American-dominated institution, though as its membership grew it became progressively harder for the US to control. The North Atlantic Treaty Organization, Southeast Asia Treaty Organization, and bilateral treaties worldwide also served American policy under the guise of “collective security” against the Soviet threat.

All these arrangements were fortified by the principle articulated in the Truman Doctrine of 1947—that aggression must be stopped everywhere. Such a commitment “assumes that foreign conflicts feature evil aggressors and innocent victims,” as Hendrickson writes. This unexamined assumption was endorsed and promoted by leaders from both political parties, who helped sustain an atmosphere of perpetual moral crisis during the cold war. The US, working through the CIA, helped to overthrow elected left-leaning governments in Iran, Guatemala, Congo, Brazil, and Chile. Interventions anywhere could always be rationalized as counterinterventions against the allegedly omnipresent Soviet threat.

Advertisement

When the cold war ended, the US’s geopolitical rationale for military interventionism—the need to contain communism—swiftly disappeared, as the country found itself in the heady position of being the world’s sole superpower. This was what is now viewed, with some nostalgia, as the unipolar moment. And yet even in the absence of its longtime ideological rival, the United States continued to conduct foreign policy with the same moral fervor that had informed its actions in the cold war, and with the same confidence that it was a force for global good.

Under the presidency of Bill Clinton, much of official Washington began to believe “that US empire would best be served by the promotion of democracy abroad—or at least an American version of democracy—on the grounds that US security, free market economies and democracies are mutually reenforcing,” as Bulmer-Thomas writes. The rationale for democracy promotion, in the words of Clinton’s first National Security Strategy, was that “democratic states are less likely to threaten our interests and more likely to cooperate with the US to meet security threats and promote sustainable development.” This formulation could work in some circumstances, but not all. Other nations could have good reasons to see democracy promotion as a form of aggression, as Russia did when Clinton sought to expand NATO eastward despite the promises made by his predecessors in the first Bush administration and the warnings of many seasoned diplomats, led by George Kennan.

Establishing “US hegemony across the globe,” in Bulmer-Thomas’s words, was not only about promoting democracy abroad but also about maintaining military supremacy everywhere. In 2000, despite cuts in personnel and the closure of many US bases, the Defense Department committed itself to the pursuit of “full spectrum dominance.” This goal, outlined in Joint Vision 2020, the Department of Defense’s blueprint for the future, meant the worldwide control of land, sea, air, and space, including cyberspace.

The triumphalist mood following the end of the cold war also emboldened neoconservative ideologues. Two of them, William Kristol and Robert Kagan, founded the Project for the New American Century in 1997. Its “Statement of Principles” pledged to “rally support for American global leadership” through “a Reaganite policy of military strength and moral clarity.” This was nothing if not an exceptionalist, even unilateralist creed, based on faith in the uniqueness of America’s position as a global leader. It evoked Secretary of State Madeleine Albright’s claim that the US was “the indispensable nation.”

The neoconservatives found their president in George W. Bush. Even before the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, Bush began to implement neoconservative policies, withdrawing from international organizations and agreements—including (in June 2002) the Anti-Ballistic Missile Treaty with Russia. This decision, according to Ivo Daalder of the Brookings Institution and other critics at the time, signaled a swerve in US nuclear strategy from deterrence to “war-fighting.”

The terrorist attacks on the World Trade Center and Pentagon provided a new enemy, international terrorism, that was even more shadowy and elusive than international communism had been. Widespread panic among Americans and their allies was taken (especially in the US) to justify a permanent state of emergency, with damaging consequences for civil liberties and public debate at home, as well as for the many thousands of civilians who would become “collateral damage” in Iraq and Afghanistan.

After September 11, new rationales for military intervention abroad emerged—not only preventative war against terror (the false justification for invading Iraq) but also R2P (the Responsibility to Protect). As Hendrickson shows, R2P originated in the recommendation of a Canadian government commission and received a modified but contested acceptance by the UN in 2005. R2P provides a virtually blank check for using force on humanitarian grounds—an idea that has little support from non-Western nations. In practice it vitiates a central assumption of international law—that each state has the right to defend itself. In his second inaugural address, Bush spelled out the vision of universal empire behind R2P: “The best hope for peace in our world is the expansion of freedom in all the world.” This was the Truman Doctrine on steroids.

Hendrickson thinks American disregard for international law helps explain the incoherence of contemporary strategic thought. According to exceptionalist ideology, the US is the primary guardian of international law, on which global stability depends. Yet Hendrickson (like Bulmer-Thomas) makes clear that more often than not, the putative rule-maker has in fact broken rules and acted in ways that it would not tolerate from any other nation.

The American exceptionalist double standard is especially apparent in its current military operations overseas. Consider the battle-ready presence of the US Navy in the South China Sea. Imagine a rival power behaving as aggressively in the Caribbean, lecturing us on our misdeeds (as we have lectured the Chinese) and appointing itself a neutral umpire for the region. A retired Chinese admiral, quoted by Hendrickson, puts the matter succinctly: the US Navy in East Asia is like “a man with a criminal record ‘wandering just outside the gates of a family home.’”

Or take the confrontation emerging on the western border of Russia. The missile defense system installed by NATO on Russia’s doorstep, combined with NATO troops conducting military exercises, could not be more provocative. No great power, least of all the United States, would allow deployments so close to its borders without protest and (probably) retaliation.

While Bulmer-Thomas treats imperial expansion as a continuous feature of American history that has run afoul of historical circumstance, Hendrickson reconstructs an anti-imperial tradition in Anglophone thought, which he calls “liberal pluralism” and recommends reviving in view of our crumbling American empire. In his view, liberal pluralism was embodied in the system of European nation-states (the “Westphalian system”) that emerged from the Thirty Years’ War. It was also the worldview of America’s founders, uniting Washington, Jefferson, Hamilton, and Madison in their suspicion of military adventures abroad. From the liberal pluralist perspective, war is the summum malum of international affairs; respect for the sovereignty of other nations is the best way to avoid it. Sovereignty is the core of international law: every state has the right to defend itself from external attack; none has the right to interfere in the internal affairs of another.

The fact that liberal pluralism discourages interference does not, however, imply that it encourages nations to be passive bystanders in the face of immoral foreign policies, as contemporary political theorists who favor an interventionist approach like to claim. Liberal pluralism “does not,” Hendrickson insists, “dictate indifference to human rights”; it allows states to shelter dissidents and welcome refugees from oppression. “What it does not allow is coercive intervention in a foreign country to secure those rights.”

Hendrickson concentrates his criticisms on the reckless use of military force in foreign lands; he does not dismiss economic sanctions as an alternative. Nor does he rule out interference in extreme situations, such as the threat of genocide. But he insists that such interventions be—as far as possible—multilateral, peaceful, and respectful of international law. He proposes maintaining NATO, but with our nuclear guarantees to its members on a strictly “no-first-use” basis; preserving friendships with allies but also working out “rules of the road with putative adversaries.” He argues that fighting terrorism requires effective policing at home and the support of functioning governments abroad, not their overthrow. The liberal pluralist tradition, in his view, provides intellectual resources for reducing international tension and redirecting national wealth toward urgently necessary aims—rebuilding infrastructure, reviving the welfare state, and addressing the menace of climate change and oceanic catastrophe.

In recent years, popular support for imperial adventures has waned. Large majorities have opposed sending US troops to Libya, Syria, and Ukraine. The percentage of Americans who think it is “very important” that the US should “maintain superior military power worldwide” dropped from 68 percent in 2002 to 52 percent in 2014. And poll respondents ranked military supremacy sixth out of ten among foreign policy aims. The top-ranked goal was “protecting the jobs of American workers.”

The shift in public opinion is a response to a series of failed interventions: efforts at regime change in Iraq, Libya, and Syria have left behind chaos, failed states, terrorist recruits, and endless war. But whatever disagreements they may have had over policy details, all three presidents since September 11 have shared a commitment to US global military supremacy. No major policymaker wants to admit publicly what many suspect privately: that America’s imperial reach has begun to exceed its grasp. Barring a dramatic shift in public discourse, the American empire will not go gentle into that good night; more likely it will, as Dylan Thomas counseled the old, “burn and rave at close of day.”

No one burns and raves more flagrantly than Donald Trump. The failure of blank-check interventions fed the discontent he exploited in the 2016 campaign. Yet his chauvinist posturing has turned out to be little more than a belligerent, unhinged version of the militarized globalism he claimed to displace. So Trump lurches from one outrageous provocation to another while most of his critics repeat the stale formulas of global leadership. Neither side seems to notice that the rest of the world does not want to be led (though some countries may still want their security to be guaranteed by US power). More and more foreign countries are trying to go about their business on their own, even in areas once assumed to be vital to the US national interest—Latin America, the Middle East, the South China Sea, even the Korean peninsula, where the South Koreans have done what American leaders were unable or unwilling to do: initiate diplomacy with North Korea.

Other pillars of American power are also crumbling, as Bulmer-Thomas demonstrates in detail. Multinational corporations are no longer as dependent on American policies abroad for access to foreign markets; General Motors, for example, now sells more cars in China than anywhere else on earth, without benefit of a US presence there. Recent years have seen a steady fall in the US net investment ratio (gross investment less the consumption of fixed capital), both private and public. The consequence has been a decline in infrastructure (including public education), as well as a slowing of innovation and productivity. At the same time, neoliberal politicians in both parties, committed to cutting back the “entitlements” provided by the welfare state and privatizing the public sector, have underwritten the rise of inequality and social immobility. The effect has been to undermine the broad prosperity that was the domestic basis of the semi-global empire.

International institutions, rather than reinforcing American hegemony, challenge it. The UN, the IMF, and the World Bank have all proven unreliable in promoting US interests. At the UN, the US is more isolated than ever on the Security Council, as the dramatic increase in American vetoes shows. Various countries have learned to avoid borrowing from the IMF, with the onerous conditions it imposes, by building up their foreign exchange reserves and paying off existing debts. The World Bank now has two significant rivals, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and the New Development Bank (which represents the BRICS countries: Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa). The Organization of American States has been superseded, since 2011, by the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States, which insisted on the inclusion of Cuba despite US opposition. China is creating its own version of the Trans-Pacific Partnership without US participation, as well as expanding into sub-Saharan Africa and cutting a deal with Nicaragua for another isthmian canal.

Yet Trump and his opponents in the Washington consensus still envision a unipolar world, where the United States can ignore the legitimate claims of rival nations and do pretty much whatever it wants, whether because of its sheer greatness (Trump) or its exceptional goodness (Clinton et al.). Obama was cautious about intervening in Syria and eager to negotiate with Iran, but his administration maintained or intensified commitments to global military supremacy, blanket surveillance, targeted drone assassinations, and modernization of nuclear weapons, as well as engagement in the Middle East and East Asia. Fundamental policies persisted despite Obama’s misgivings.

Neither Bulmer-Thomas nor Hendrickson believes these policies can continue without catastrophe. And it might, in any case, not be in the US’s interests for them to continue. As Bulmer-Thomas reminds us, “Imperial retreat is not the same as national decline, as many other countries can attest. Indeed, imperial retreat can strengthen the nation-state just as imperial expansion can weaken it.” Yet as Hendrickson concludes, “It is crystal clear that the empire is fully determined to stick around,” despite our desperate need to dismantle it. The drift of global events may eventually require the United States to acknowledge the reality of a multipolar world, but we cannot assume that the process will be peaceful. Still, Hendrickson has performed an urgently necessary service in reconstructing the liberal pluralist tradition. He reminds us that there is a humane alternative to contemporary orthodoxy, if we can only recognize it.

This Issue

February 7, 2019

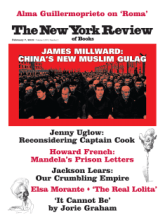

‘Reeducating’ Xinjiang’s Muslims

The Twisting Nature of Love