In the 1970s, impecunious and unknown, the only way I could get into the legendary Studio 54 was under the sponsorship, so to speak, of someone older and more established. The velvet rope parted only one time; it wasn’t the night Bianca Jagger rode across the dance floor on a white horse, but it was close.

There was a balcony where you could go if you were seriously tripping, as I was, to get out of the mayhem. That night the rows of theater seats were empty except for a few couples making out in the back. I collapsed into a chair. When my eyes adjusted to the dark, I became aware of someone else in my row. There he was, solitary in the shadows, standing with his arms crossed and one hand to his chin, staring at the revelry below. The trademark wig, in the pulsing light of the dance floor, looked not so much silver as made of straw. He glanced at me briefly, seemed about to speak, changed his mind. I was of no interest to him, just another stoned kid.

Andy Warhol combined social and pictorial intelligence in a way not seen in this country since John Singer Sargent. In one of the most unexpected artistic transformations of the last century, he found a way to make a highly synthetic, semimechanized kind of painting feel authentic. His attitude and posture, his public persona, and his forays into filmmaking and other media were radical in the world of high art, but his aesthetic inclinations were more traditional. They harked back to, and partially bridged, two widely divergent tendencies in American art: social realism and abstraction, the Yankee peddler and the Transcendentalist.

Warhol was many things, but at heart he was a salon artist with acute instincts for social engagement. The complexity of his persona, the sociocultural upheaval of the 1960s that he helped to advance, and his impact on generations of activists and aesthetes have been discussed at length. And while central to the Warhol mythology, they are not the reason why his best paintings still pull us into their aura. We’re looking at them today because of their unique amalgamation of photographic facticity with a painterly directness and stylishness that stops just short of aggression. Warhol understood the visual power of rhythm and repetition—minimalism before it had a name. He also sensed that the relationship between content and style could be deliberately misaligned to create a new kind of pictorial irony.

At the beginning of the 1960s, Warhol’s work looked new because of a technique new to art—the half-tone silkscreen. It was the ultimate low-to-high inversion. Screen printing uses the method by which photography’s gray scale, its range of lights and darks, is translated into a pattern of tiny dots; it’s what allows photographs to be reproduced in newspapers. The same dot pattern, expressed as tiny, pin-prick holes, can be bonded to a piece of silk, which is then stretched taut on a frame of wood or metal. When ink is forced through the silk using a rubber squeegee, the photographic image, reconstituted by the tiny dots, appears on the printed surface—in Warhol’s case, the canvas. The print can be repeated any number of times, and the amount of ink used, as well as the degree of force applied to the squeegee, will produce variations in the resulting image.

Warhol was the first artist to grasp the potential for pattern and rhythm released by the screen-print process; it could be both mechanical and expressive at the same time. This pictorial rhythm was tied to a feature of the silkscreen: it exaggerates the contrast in a photographic image between light and dark, amplifies their power to convey a sense of form, and also makes the dark areas of a photograph feel almost animated. In a profound act of poetic equivalency, Warhol further realized that the true substance of photography is the shadow cast by and on its subject. This was the essence of his major innovation, which still reverberates today: the reciprocity between painting and printing. What was his alone was the identification with the fatalistic glamour of a shadow.

Most importantly, the silkscreen brought the world outside the studio—the unfiltered world of headlines, of heartbreak, stardom, and catastrophe—into the heart of painting. Warhol hitched his sensibility to the values of the picture press, to hard-luck stories of exceptional bathos, and to an emotionality and sensationalism not previously welcomed into the upper echelons of art. The work got interesting when he boldly, and also a little fatalistically, tried to integrate that sensibility with the sweeping grandiosity, aloofness, and froideur of a painting by Clyfford Still or Barnett Newman. He did this by letting the weights and rhythms of the black silkscreen ink, as it accumulated or thinned out, move one’s eye through the picture at the same time that it absorbed the image. What those artists accomplished with a palette knife or a brush, Warhol approximated using his squeegee. His paintings work best when you can feel him reaching for the grandeur and clear-eyed sorrow of classical art. To these qualities he added a sweetness that was not common in formalist art, and that was all his own. The underlying drama in a painting by Warhol is the nerve and daring to say, “Why not this? Can’t this be art too?”

Advertisement

Andy Warhol was born in Pittsburgh in 1928, the youngest child of Slovak emigrants. His father was a coal miner. They were poor; it was the Depression. He was a sickly, introverted, and adored child who liked movie fan magazines, the icons at his Byzantine Catholic Church, and other boys. His early flair for drawing won him a place at the Carnegie Institute of Technology, where he excelled in the traditional course of study, drawing from plaster casts and the like. After graduating in 1949, Warhol came to New York to make his name as a commercial artist.

In the early 1950s, before photography changed the look of print advertising, illustration was used to enchant and seduce the consumer. An illustrator with a distinctive style could go far, and Warhol rapidly established himself as one who could confer wit and sophistication on consumer products. His whimsical drawing style and elegant, fanciful typography (often the work of his mother, who was, at times, a creative partner) made him a favorite of art directors and clients, and eventually led to a steady gig drawing the ads that the I. Miller Shoe Company ran weekly in The New York Times. I. Miller was Warhol’s grad school, an efficient education in how to focus the reader’s gaze and keep her from turning the page. Certain things worked, others not so much, and Warhol learned to eliminate anything that didn’t contribute to the desired effect.

Having reached the top of the commercial art world, Warhol had a much bigger idea of his own talent, or of his own drive; his sights were always on the world of elite galleries and museums. At first he didn’t understand the difference between illustration and art—why a drawing by Jasper Johns cost so much more than one of his own. He eventually figured it out. If anything, it was a surfeit of personality that cast his work in a different, lesser light. Warhol wasn’t born cool; he became so.

The Whitney Museum of American Art has mounted a large, mostly buoyant survey of Warhol’s immense output, “Andy Warhol: From A to B and Back Again,” and it expands our understanding of the origins and evolution of his sensibility. The exhibition presents the artist in full: he was not only, or even primarily, a painter but also, at various times, a filmmaker, magazine editor and publisher, author, illustrator, photographer, diarist, TV show host, stage designer, and political activist. The veteran curator Donna De Salvo has done a real service in examining heretofore neglected aspects of Warhol’s oeuvre: not just the films, but also his early drawings and witty erotica, the many commercial illustrations and book designs, the paintings made in collaboration with Jean-Michel Basquiat, and the late forays into abstraction. The overall impression is that throughout his life Warhol was always an exceptionally hard worker who adapted as times changed, but one who largely confined himself to the surface of life. After 1968, he produced a steady stream of paintings on any number of themes and subjects, but didn’t deeply inhabit more than a few of them, the same as most artists. He preferred to keep the carousel moving at a steady clip.

It might be difficult, in this time of critical approbation and market adulation, to grasp just how devalued Warhol had become by the early 1980s, even among his own inner circle. In 1985, when the Saatchi Gallery opened with a small survey of 1960s paintings, Warhol’s business manager, the sartorially peerless Fred Hughes, confided to a friend that it was the first time he took Andy seriously as an artist. When Warhol died in 1987, an appreciation in The New York Times by John Russell struck a less than sanguine note: “Posterity may well decide that his times deserved him.” Parts of the art world had grown weary of the “Warholization” already underway, and some critics were pushing back. The art historian Barbara Rose had recently begun a review with this zinger: “Andy Warhol has sunk back into the commercial ooze from which he emerged.”

Advertisement

If he was the artist America deserved in 1987, it now seems that each era shall have the Warhol it deserves, and the version that emerges from the Whitney show is much more up front about queer culture’s contribution to the visual arts and to the evolution of our current sensibilities. In tandem with presenting queerness as a category of experience and identity in art, the Whitney show gives us an insight into the young Warhol: Andy with a sketchbook, Andy the fan, the fashion Andy, Andy the ardent youth dreaming a life of style and erotic possibilities.

Perhaps as a result of emphasizing the “artist as a young striver” version of Warhol’s life and times (a version he would likely have approved of), the show feels rather light on masterpieces, though it more fully fleshes out how his lifestyle informed his development. De Salvo points out the links between Warhol the precocious teenager, making charming, romantic pencil portraits of his friends, and the Pop artist who painted portraits of Coke bottles and other products.

A large retrospective exhibition often tells a story about an artist influenced by other artists as well as the broader culture, about how and to what extent artists adapt and evolve. The story can also be about an artist’s relationship to his materials. This show’s arc is the story of line supplanted by image. Warhol’s early sensibility was expressed almost exclusively through line. He showed only passing interest in academic modeling, shading, creating volumes, relational composition, and the like. He was a display artist who thought in column inches, not in paint. The young Warhol had instead a feeling for how to style his line so that it drips with personality, and also how to use line to imply a narrative. The two qualities together define a current that, while not exactly suppressed in the macho art world of the 1960s, was hardly valorized. Today, that aspect of Warhol’s art feels irresistible, something happily passed forward to our time.

The exhibition’s first couple of rooms reveal Warhol in possession of a great lyrical charm, to which has been added the graphic punch of superior packaging design. One wall has been given over to a salon-style hanging of twelve gold-leaf drawings of shoes from the 1950s. In these works, the shoes, some with pinched toes and high button uppers or dainty bows, feel Victorian; it’s often the case, and was especially so in the late 1950s and early 1960s, that the look of “sophistication” borrows its appeal from something antique. The drawings are hung on top of black-and-white reprints of the I. Miller ads and other drawn images that appeared in the Times—shoes on top of more shoes. The whole thing looks chic and delicious. You want to have it wrapped up and sent as a present to Eloise at the Plaza.

Apart from his mother’s fanciful, hand-lettered script and Pennsylvania’s robust nineteenth-century folk-art tradition, the biggest influence on Warhol’s early stylized drawings was Ben Shahn, a working-class humanist who today might seem light-years from Warhol’s world but who was, at the time, one of the most popular artists in America, and who provided an example of how to bridge the gulf between fine art and illustration. Warhol’s version of Shahn’s urgent, searching—one wants to say moral—broken line was made by applying ink to wax paper and then blotting the tiny ink blobs with drawing paper, which produced a distinctive graphic insouciance in which every depicted object, even a shoe, seemed to have a pursed cupid mouth. Warhol also made elegant drawings using a ballpoint pen, which gave a more continuous, flowing line. Those drawings are, if anything, even more romantic than their ink-blot cousins, and have more in common with Jean Cocteau than with Shahn.

As time went on, Warhol wanted something more ambitious for his art but was unsure where to look for inspiration. The show’s inclusion of his developmental years allows us to see the small jumps he made in the progression from illustrator to painter, how the fascination with the picture press and the printed page were turned into ideas about what to paint and how to paint it. So great is the sense of logical development and discovery that, walking through the first rooms of the show, we feel that we might finally learn the answer to the great mystery: How exactly did Warhol make the leap from illustrational, line-based imagery to the first silkscreen paintings? We can feel him straining at the threshold of Pop art, but we can only imagine what it must have felt like to grasp that painting and printing could be one and the same. It was subversive and liberating. It was a new kind of paintbrush.

Almost at the same moment, Robert Rauschenberg also introduced silkscreen images into his paintings, after first seeing the large industrial screens in Warhol’s studio. He used the screens in a cubist-collage sort of way, the images often painted over or otherwise altered, and always subsumed into a larger composition. The images have a scrapbook quality to them; they are often nostalgic, even elegiac, phrases or cantos in Rauschenberg’s ongoing visual tone poem.

Warhol, by contrast, quickly recognized the sheer graphic power as well as the transformational nature of the silkscreen image itself—how it confers on any subject a drama of light and shadow, an urgent aesthetic bounty grounded in the photographic now. Wielding the silkscreen like a shield, Warhol progressed from a graphic, outlined image to one made by a decisive drag of a big industrial squeegee. You can feel the expressive currency of the materials coming alive in his hand; the mystery of the photographer’s darkroom is invoked with each pull. Such was the galvanizing force of photography that it swamped Warhol’s hand-painted style all at once, and by late 1961 the transition was complete. It would be another twenty-five years, more or less, before he again chose drawing over photography.

The silkscreen gave his art heft; its use at the grand scale of the New York School conferred gravitas and turned Warhol into a painter of modern life. It gave him access to an enormous range of subject matter that could be transferred quickly to the canvas, and at any scale. Movie stars, Mao, violent accidents, society portraits, skulls, pistols, flowers, ads, and much more—all were delivered up by the same technique.

Warhol’s reliance on the silkscreen’s inherent drama is a good example of an artist turning his liabilities into an asset. His paintings are, by design, all surface, the image as thin as the layer of ink used to conjure them. They couldn’t be simpler, or, in a way, more humble. Despite, or because of, these limitations, his work from the 1960s turns out to be among the most durable painting of the last sixty years.

For decades, Warhol’s paintings were first-class décor, a term that is in no way derogatory; apart from the image, they have gridded rhythm and great scale and often feature surprising, even sizzling color. They can be absorbing, but in a way that differs from earlier paintings. They can make any room look smart and chic, but you wouldn’t want to hang one next to a De Kooning. At the right size they have the unarguable, declarative quality we associate with major art. Sometimes their presentational decisiveness is the very thing that stops them short. (Is that all there is?)

At their best, Warhol’s paintings connect us to a state of contemporaneity, of hipness and glamour, of being in the right place at the right time, and to a feeling of mild transgression. When you’re not in the mood to feel those things, they can strike you as manipulative, as trying too hard, or, conversely, not trying hard enough. The curator Henry Geldzahler liked to tell a story about visiting Warhol’s studio in the 1960s and observing about a painting that Andy had “left the art out,” to which Andy, droll as ever, replied, “I knew I forgot something.” Humor aside, there was something about Warhol’s working method that made the art component conditional. The art had arrived as if by magic, and it left open the possibility that it could just slip away without anyone noticing.

Two rooms after the golden shoes, the exhibition gives us a sampling of the Death and Disaster series on which Warhol’s reputation largely rests, and which would occupy him through the amphetamine-fueled years that ended with his near-fatal shooting in 1968.These include the stellar 1963 silkscreen painting Suicide (Fallen Body), which looks like it was made from a police photograph but was in fact from a picture published in Life. With its sixteen frames, it has the implied motion of a sequence by Muybridge, with the stuttering repetitions of the image in a grid, black over silver, creating a kind of image-foam that coats the painting’s surface in inky, iridescent waves.

In those frames we see a young woman, elegantly dressed in a dark skirt suit and white blouse, reclining on what appears, improbably, to be the hood of a car. We are looking from the top of her head, up over her body to her crossed legs, where we notice that one foot is bare. At first, the woman appears to be resting, reaching to touch a string of pearls. Her dark hair is still tastefully swept up from her unblemished forehead. There is, however, something not quite right about her pose.

Warhol’s paintings present the glamour of celebrity on a continuum with nightmarish American imagery: grisly car crashes, electric chairs, race riots. The flashbulb equally illuminated all. His work suggests that they were in fact inextricably linked. Warhol cultivated a radical openness to this world of images, as well as the states of mind and of being that the photographs capture. This openness extends to the Race Riot paintings from 1963–1964, which, along with the suicides and other disasters from around the same time, reveal Warhol to be a trenchant social critic. His Race Riot pictures are still shocking in their casual brutality. They don’t condescend to the audience, and more than any others from that time, they bring the reality of the streets into the museum.

Feelings of outrage and shame still emanate from Mustard Race Riot (1963), a syncopated, stacked grid of three views, made from press photos, of a stylishly turned-out black man being set upon by a police dog. The painting, in freezing the action forever, is both witness and judge: that man with his straw trilby and that cop and that dog enacting their aggrieved appointment with fate. This still strikes me as radical for an artist who consistently courted commercial success. It’s as if Jeff Koons, while turning out balloon animals and other odes to childhood, also made highly refined stainless steel sculptures of unarmed young black men being shot by police. That is something we are not likely to see.

If Warhol had made nothing more than the Race Riot and the Death and Disaster pictures, he would still be a major figure in the history of pictorial art, but there was so much more to come. He was a disciplined artist, and the list of his painted images is long: the car crash and suicide pictures; the electric chairs; Marilyn, Elvis, Brando, and all the other stars and celebrities; the flowers; the large Maos; the skulls; the hammer-and-sickle pictures; the excellent Shadow paintings and the ads—subject matter was never Warhol’s problem. However, his method didn’t evolve much, and as the work continues through the 1970s and 1980s a sameness creeps into it.

Like every artist, Warhol had highs and lows, periods of sustained creativity and longer periods of treading water, waiting for inspiration to strike. Or perhaps his attention was simply elsewhere—he was involved in many non-painting projects at any given time. It’s also possible that he came up against the limits inherent in his technique; the silkscreen translated everything the same way. It was mechanical, after all, which can cut both ways. The unwelcome but undeniable impression made by the Whitney show is that after the 1970s, some of the light goes out of his painting.

Still, innovation continued until the end. In the early 1970s Warhol gave freer rein to his more painterly impulse in the colored grounds underneath the silkscreen images. His paintings of the 1970s take on a more nuanced polychrome palette and more active, vigorous brushwork. I used to think the large portraits of Mao (who was still very much alive in 1972, when Warhol began painting them), with their large blocks of color and brushwork that underlie and surround the Chairman’s countenance, were some of the best things that Warhol made. You feel him putting to work everything he knows about painting and, with their scale and stateliness, they are impressive in their combination of what the paint is doing along with the pattern of lights and darks of the silkscreen image itself. The energy of the wet-into-wet painting, alternately contained within the image and set free from it, works in frothy counterpoint to the filigree of tiny black dots that magically reconstitute the face of Mao.

There is one Mao portrait in the Whitney show, but unfortunately it is not completely successful. At fifteen feet tall, it bridges the gaps between Abstract Expressionism, Pop irony, things-as-they-are facticity, and a technologically enhanced image: the attitude that would come to be called postmodern. But the integration of the brushstrokes with the image is not particularly acute; their scale is too small and fussy to act as a counterweight to the Chairman.

Starting sometime in the 1970s, Warhol introduced another of his pictorial inventions. He began using a new kind of line, one made by tracing around projected images with a brush. The brush follows the conture as well as the interior shapes of an image—say, a face or the facets of a perfume bottle. Lightly loaded with black acrylic paint, it very quickly starts to go dry, producing a skipping kind of brush mark, called “dry-brush,” an update of his original blotted line drawings of the 1950s. First used as an overdrawn line on top of silkscreen images, almost like a second view of the same image, Warhol eventually allowed the brushed line to stand on its own, and finally, at the very end of his life, jettisoned the silkscreen altogether.

The way that he traced a logo, or signage, or a version of Da Vinci’s Last Supper, or an image of Judy or Liza, was as distinctive as the silkscreen, while also achieving a more artisanal, audience-friendly, even jaunty and upbeat result. The casual-seeming brushed, traced line breathed new life into his work and made his images feel as immediate in their way as the silkscreens had felt in the 1960s. Some of the best examples appear in the Last Supper series, which were among the last things Warhol painted, though the one in the Whitney show obscures the dry-brush effect by fusing it with yet another later innovation, an all-over pattern of camouflage color.

There were other developments in the 1980s, most importantly a group of paintings made with Jean-Michel Basquiat. Warhol and Basquiat were friends, they shared a taste for nightlife, and they also shared a dealer, Bruno Bischofberger, whose Zurich gallery was a kind of Warhol outpost and who I believe suggested the collaboration. Although dismissed at the time as a market stunt, the paintings today look vitally alive. The artists’ respective strengths are emphasized, their weaknesses shored up. Basquiat gave Warhol’s work spontaneity, polyphony, and skeins of jumpy marks full of personality; Warhol gave Basquiat structure and mainstream Americana.

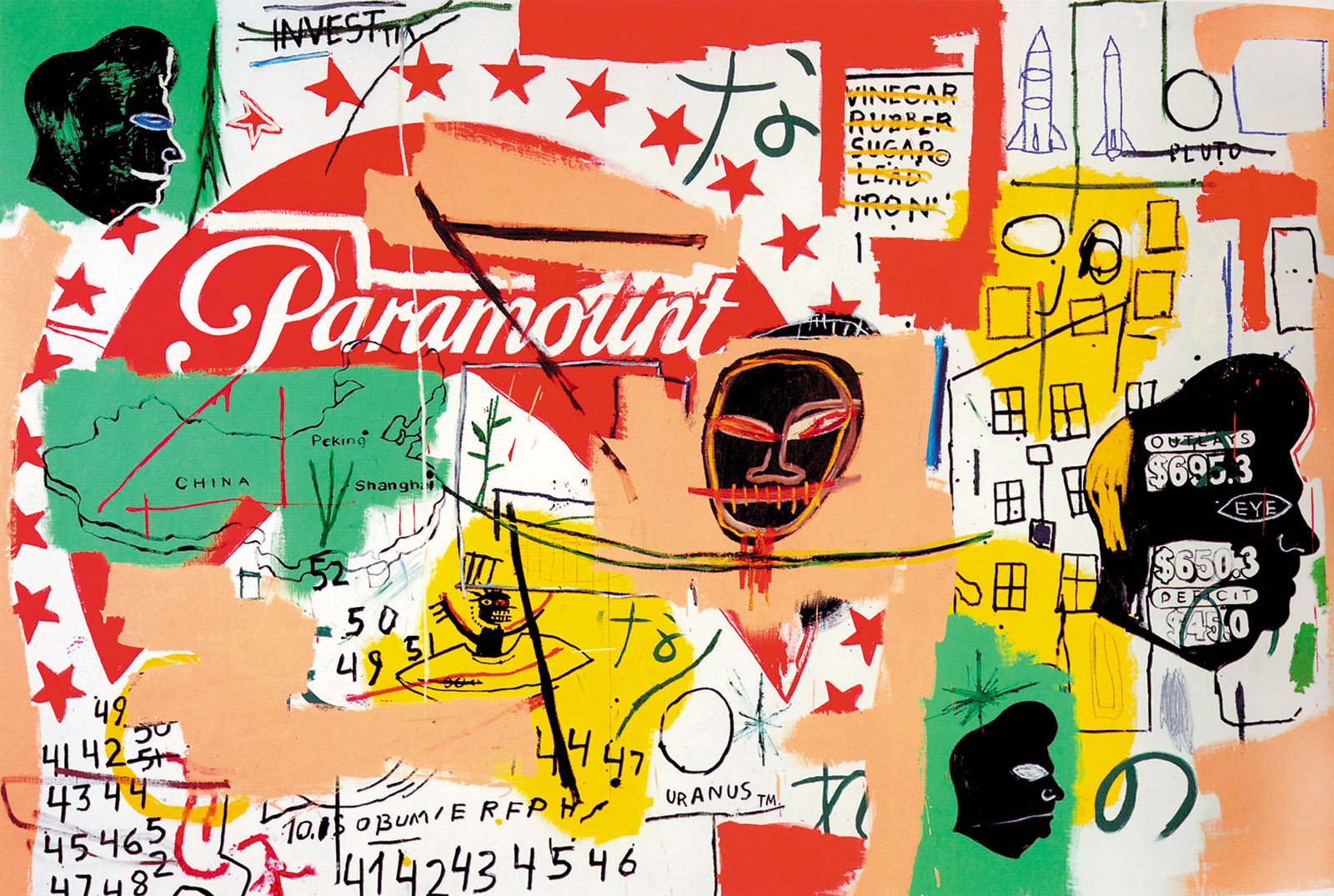

Two of their collaborations, Paramount from 1984–1985, and Third Eye from 1985, are in the Whitney exhibition, and they are by far the most energized paintings in the final galleries. Paramount is more Basquiat than Warhol; the Pop master’s contribution is a red-on-white rendition of the Paramount Studios logo, which covers roughly half the canvas. Over this, the younger artist has brushed in areas of green, salmon pink, and cadmium yellow medium—tautly calibrated colors that are overlaid and interwoven with oil-stick drawings of heads, building façades, columns of numbers, rocket ships, and the names of raw materials like sugar, iron, and lead. The whole composition is jumpy, wildly unstable; shapes and marks and images are all swimming in the same turbulent waters, along with the artists themselves.

Artists’ reputations are always being adjusted. Time plus distance lessens the sense of urgency for artists of a younger generation. For the majority of art professionals today, Warhol’s position as an avant-garde colossus is unshakable. And much of the work of the last forty years—that of the “Pictures Generation” in particular, not to mention the art world’s ongoing appetite for painting moguls—would probably have been very different without his example. Perhaps because his legacy has entered visual culture in such a broad and commercial way, many young artists have broken free from his orbit. I have heard from some young painters just how little the whole Warhol phenomenon concerns them. One told me that for her, the Triple Elvis painting in the show, which for collectors would be a diamond as big as the Ritz, is “like wrapping paper,” that is to say, one step down from wallpaper.

Few opinions I’ve heard have been as dismissive, and it’s not a question of right or wrong; the point is simply that all artists are subject to the vagaries of fashion. Warhol’s good early pictures are very good indeed, their originality and pictorial power still stun, but they are no more transcendent of the time in which they were made than is most other art. The later work especially is time-specific, and not always as substantial as one had remembered; it didn’t help that Warhol’s career was cut short. It’s easy to imagine another great flowering—or several—had he been granted more time. Walking through the show, especially as one gets to the later rooms with the last ten or fifteen years of work, one finds that Warhol’s style begins to seem not so much a revolution in pictorial form as simply one artist’s answer to the question of how to paint an image.

So much of Warhol’s art was aimed at capturing a moment of social truth, be it beauty, glamour, camp, or power, in the guise of a portrait, and his assiduously cultivated portrait business partly financed his many other activities. Of the many hundreds of portraits Warhol painted over the years, special attention, even love, seems to have been given to his dealers and fellow artists: Irving Blum, Henry Geldzahler, Leo Castelli, Roy Lichtenstein, and Man Ray. In these and other portraits, Warhol shows all the sensitivity and psychological insight of a traditional portraitist. Eighty-four of the portraits are featured in a separate room of the exhibition, and it’s fun to point out the faces one recognizes, some of them friends or well-known social figures from another era: Look how young!

There is a knot of pathos in the portraitist’s art: the sitter will never again appear as youthful, as glamorous, as desired as now. This eternal present also comes with the knowledge that it has already slipped into the past. Even Warhol’s portraits of buildings, of symbols like the hammer and sickle, the children’s toys, the perfume bottles, and of course the skulls, are memento mori. In all of these paintings and drawings, Warhol is making a connection to his beloved nineteenth-century folk art, to the theorem stencils of flowers and the embroidery sampler with its common motto: When this you see/think on me.

This Issue

February 21, 2019

Men’s Lib

The Fake Threat of Jewish Communism