1.

Some writers become imbued with the charisma of a history, well beyond the charisma of their writing, and one of these is Ernst Jünger. This was partly because he lived through the entire experiment in historical mayhem produced by the European twentieth century—he was born in Heidelberg in 1895 and died in 1998, at the age of 102. But the mystique he enjoyed and cultivated was really a product of early youth. Jünger ran away from school to join the Foreign Legion in 1913, and the following year enlisted in the German army to fight in World War I. He served with distinction on the Western Front, a landscape of spectral horror that he evoked in his first and best book, Storm of Steel, a celebrated memoir composed of raw chunks of close-up, uninterpreted detail whose emblem might be the corpses he depicted with such panache and such severity: “A headless torso was jammed in some shot-up beams. Head and neck were gone, white cartilage gleamed out of reddish-black flesh.” “One man had lost his head, and the end of his torso was like a great sponge of blood.”

Storm of Steel was a marvel of detached observation in the midst of catastrophe: “Rank weeds climb up and through the barbed wire, symptomatic of a new and different type of flora taking root on the fallow fields.” But it was also embellished with mini arias that tended to describe a theory:

Grown up in an age of security, we shared a yearning for danger, for the experience of the extraordinary. We were enraptured by war. We had set out in a rain of flowers, in a drunken atmosphere of blood and roses. Surely the war had to supply us with what we wanted; the great, the hallowed, the overwhelming experience…. Anything to participate, not to have to stay at home!

It was a German version of the romantic malady Baudelaire had diagnosed and examined with more ferocity: la grande maladie de l’horreur du domicile. The nineteenth century, with its medicine and machines and positive thinking, always had a shadow disdaining it: the reactionary dandy. Jünger was just a belated incarnation of the type. But his preferred term for it was “chevalier,” which he smuggled into a passage toward the end of Storm of Steel:

There was in these men a quality that both emphasized the savagery of war and transfigured it at the same time: an objective relish for danger, the chevalieresque urge to prevail in battle. Over four years, the fire smelted an ever-purer, ever-bolder warriorhood.

In the postwar era, Weimar Germany was all jazz and delirious freefall, but a kind of conservative resistance was incubated in the febrile atmosphere by writers like Jünger’s friend Carl Schmitt, the political theorist who attacked parliamentary democracy, preferring the rule of a dictator; and Gottfried Benn, the Expressionist poet of garish nihilism. Jünger expanded his theory of the chevalier as a way of life into an entire theory of history. In a suite of novels and essays and articles, he developed a reactionary world vision in which the lone and noble individual tried to resist mass society and its vast, impersonal technology. It was a theory he never abandoned. His lifeless novel The Glass Bees, published many years later in 1957, is a dystopian allegory that imagines what seems like a world of immersive virtual reality, of absolute tech—the natural consequence of “this trend toward a more colorless and shallow life.”

After Hitler came to power in the 1930s, Jünger was courted by the Nazi Party as a possible intellectual ally. But his version of aristocracy meant that he refused all group identification (just as his theory of the chevalier was never simply national), and so—although he had written for right-wing newspapers like the Völkischer Beobachter—he refused to join the party, just as he refused to join the Prussian Academy of Art after 1933, in its era of “synchronization” with the Nazis.

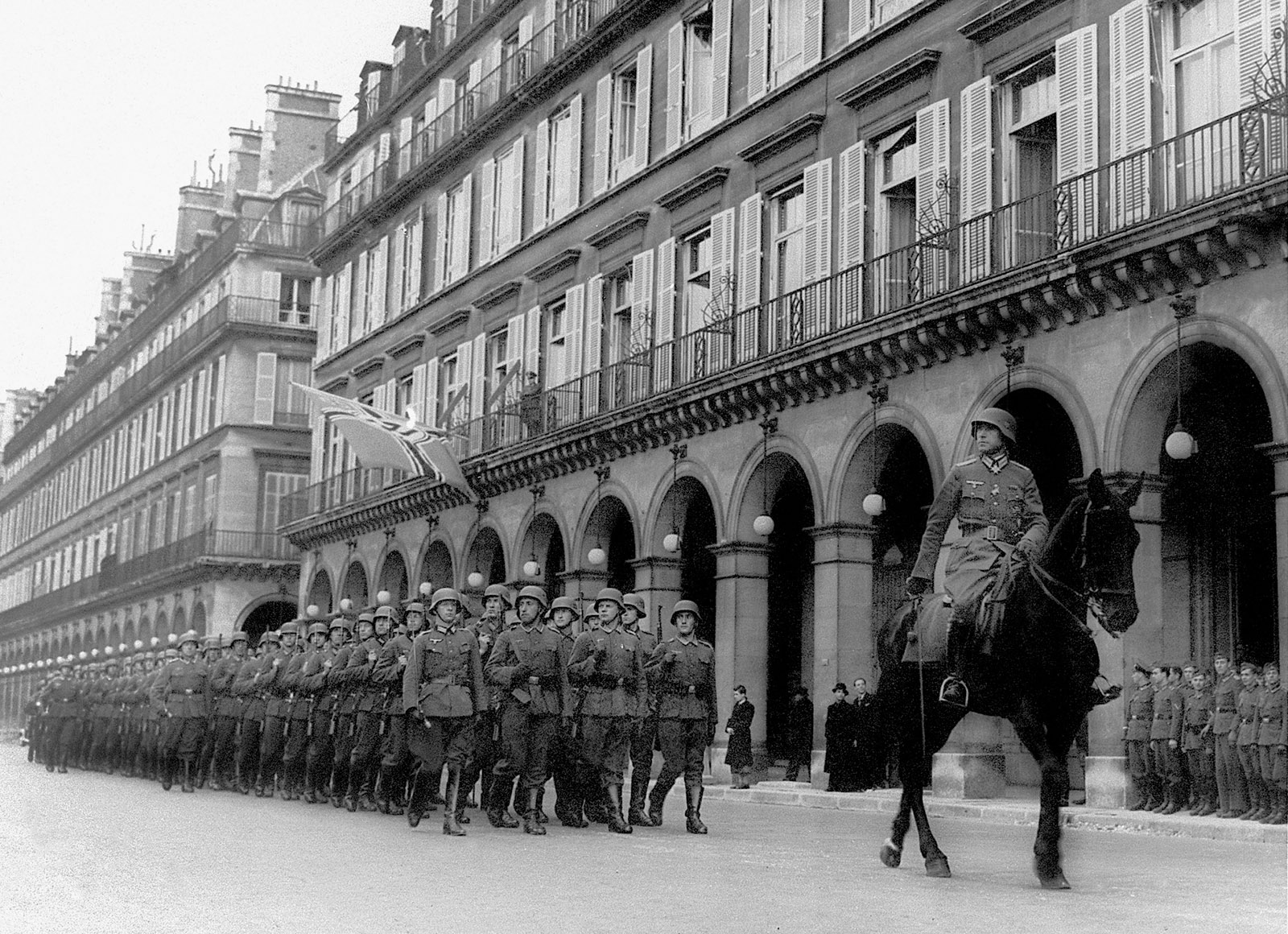

When Hitler declared war in 1939, however, Jünger was conscripted back into the German army. In April 1941 he was posted to occupied Paris, where he lived in the Hotel Raphael, with an office nearby in the Hotel Majestic. He was initially under the command of General Otto von Stülpnagel, and then Stülpnagel’s cousin, Carl Heinrich von Stülpnagel. His task in this luxurious setting was double: to gather military intelligence on enemy and Resistance activity, and to track conflicts between the Nazi Party and the army. He was a listening post, an observatory on loyalty and resistance, keeping his notes, along with his journals, locked in a safe at the Majestic.

Meanwhile he lived the life of a chevalier in occupied Paris, in the salons and the embassies. The Marquis de Brinon was a collaborator who was made a kind of ambassador to the German regime in occupied Paris by the Vichy government. At his house, Jünger met the actor, director, and playwright Sacha Guitry (“On his little finger there gleamed a monstrous signet ring with a large embossed monogram SG on the gold surface”) and the actress Arletty: “Pouilly, Burgundy, champagne, just a thimbleful of each. On the occasion of this breakfast, around twenty policemen were stationed in the vicinity.” At the home of Marie-Louise Bousquet, the Paris editor for Harper’s Bazaar, he met literary fascists like Henry de Montherlant and Marcel Jouhandeau, who wrote for the journal Le Péril juif. At the salon of Florence Gould, he met Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, and Jean Cocteau.

Advertisement

And so Jünger lived out the war in Paris—apart from one tour of the Eastern Front in the winter of 1942–1943—in a compromised haze of art and literature and pleasure:

Spent the evenings in the company of Lieutenant Colonel Andois in the Rôtisserie de la Reine Pédauque near the Saint-Lazare railroad station and, after that, in Tabarin. There, saw a floorshow of naked women before an audience of officers and bureaucrats of the occupying army seated in the front rows. They fired off a volley of champagne corks.

He performed small acts of subversion when he could, sometimes passing on information to the Resistance about deportations. But his real desperate effort at integrity was maintained precariously in a series of private journals, where he kept notes on his reading, his grandiose theories of society, his meetings and conversations, and his increasingly contorted self-reckoning as the horror of the Nazi regime became more and more obvious. These journals, which were published in German under the title Strahlungen—irradiations, beams of light—have now been translated into English as A German Officer in Occupied Paris: The War Journals, 1941–1945. They are a historical document, but they are also, in a way, an allegory.

In his novels, Jünger was pedantic, prescriptive, working in forced symbols; in his essays he tended to the rhetorical and the obscure. His single intense talent was for the spiky sporadic note form of a journal, something that proceeded in leaps and zigzags through moments of pure observation: “a man with a slender sickle mowing the grass of a railroad embankment next to a busy street and stuffing the clippings into a sack, probably collecting fodder for rabbits.” Jünger wanted his journals to be a mystical form that might reveal—despite the surface lunches—deep patterns in world history:

Concerning this journal. It captures only a certain layer of events that take place in the intellectual and physical spheres. Things that concern our innermost being resist communication, almost resist our own perception.

There are themes that interweave themselves mysteriously through the years, such as that of the inevitability that consumes our age. This is reminiscent of the grand image of the wave of life in Asian painting, or of the maelstrom in E.A. Poe.

But what’s maybe more interesting now are the patterns of guilt and self-knowledge that emerge from these journals despite Jünger’s ambiguities and obscurities. It was Jünger, after all, who provoked one of Cocteau’s best jokes: “Some people had dirty hands, some had clean hands, but Jünger had no hands.” The impression of Olympian chic was one that Jünger cultivated, but the theatrical effort behind that impression is what his journals reveal.

I don’t mean I want to judge Jünger. People in positions of safety can’t judge people in positions of danger: that might be one axiom of a moral intellectual life. And there’s no question that Jünger was in danger. In the Hotel Majestic, he wrote, “Even though I live for the most part surrounded by the trappings of comfort in this Second World War, I am in greater peril than when I was at the Battle of the Somme or in Flanders.” He wasn’t lying. Throughout his time in Paris—but especially after those close to him, including his commander, Carl Heinrich von Stülpnagel, were implicated in the plot to assassinate Hitler in 1944—Jünger was in constant peril: as close to the regime as he could allow himself to be, as close to the Resistance as he could afford. In the process, he was also exposed to a different, more everyday danger: the much slower, much less dramatic danger of corruption.

“Style is essentially based on justice,” he wrote in one entry. “Only the just man can know how he must weigh each word, each sentence. For this reason, we never see the best writers serving a bad cause.” As an aphorism, it is clearly inadequate. But as an aphorism written inside the Hotel Majestic by an officer in the German army, these sentences start to acquire a woozy, loopy energy. In Paris, Jünger tried to confront absolute horror with his chevalieresque idea of style, and the experiment is absorbing to observe, in its short-circuits and moments of illumination and ultimate burnout.

Advertisement

2.

The surface of these journals seems to be all luxury and champagne, a pointillist flurry of elegance: “At the Ritz in the evening with the sculptor [Arno] Breker”; “In the afternoon, I dropped by the bookshop in the Palais Royal, where I bought the 1812 Crébillon edition printed by Didot”; “At noon in the Ritz with Carl Schmitt….” It was as if for Jünger occupied Paris could be a laboratory of culture. “Perhaps I’m doing the right thing if I take advantage of the possibility of establishing myself here,” he writes on May 30, 1941. A few months later, in January 1942, he can still be found sampling the civilization: “In these narrow streets around Saint-Sulpice with their antiquarian bookshops, book dealers, and old workshops, I feel so at home, it’s as though I had lived among them for five hundred years.” In fact, his bibliophilia in Paris is so obsessive as to be almost disarming: “Visited Calvet in the evening at a party that included Cocteau, Wiemer, and Poupet, who gave me an autograph of Proust for my collection.”

But that comedy is the surface version of a deeper malaise, a larger problem of human thinking—just as one gradually realizes that so many of the names mentioned casually in these journals are toxic. “Dinner with Abel Bonnard on Rue de Talleyrand. Conversed about ocean voyages, flying fish, and Argonauta argo.” (Bonnard was a writer and Vichy politician who after the war was found guilty of collaboration and condemned, in absentia, to death; Franco gave him asylum.) A definition of this malaise might be to call it the malaise of the incommensurate.

On August 11, 1943, Jünger is playing chess in Paris with another officer, Kurt Baumgart, who tells him about the recent Allied bombing of Hamburg: “He told of a woman who was seen carrying an incinerated corpse of a child in each arm. Krause, who carries a bullet deep in his heart muscle, passed a house where phosphorous was dripping from the low roof. He heard screams but was unable to help.” And Jünger then adds a final comment that would be amusing in its inadequacy if what’s being described weren’t so appalling: “This conjures up a scene from the Inferno or some horrific dream.” But the real horror is contained in the tonal shift of the very next entry, on August 13, which begins, “These days I sometimes rise twenty minutes earlier in order to read some Schiller with my morning coffee, specifically the little edition that Kretzschmar edited and recently gave me.”

Everyone’s life is a montage of mismatched and incommensurate moments. But what’s revealed through the enforced montage structure of Jünger’s journals—their commitment to linear notation—is the problem of how to think within a catastrophe and the difficulty of maintaining any kind of true perspective. All his categories—a little library of nineteenth-century Kultur—were too limited. On April 6, 1942, he has a conversation with Kossman, the new chief of the General Staff: “He briefed us on the frightening details from the forests of the lemures in the East. We are now in the midst of the bestiality that Grillparzer foresaw.” Grillparzer! A wonderful writer, maybe, but nineteenth-century melodrama is no equivalent to twentieth-century genocide. What else could Jünger do? Grillparzer was his only available tool for thinking. And while Jünger’s wish to use a code in these diaries is understandable, his decision to call the Nazi executioners “lemures”—the vengeful spirits from classical mythology—is troubling too, as if the true brutality couldn’t be confronted or comprehended.

So often, the reader of these journals is dazed by the switchbacks of a paragraph break, as in this entry for July 18, 1942:

Visited the photographer Florence Henri in the afternoon. Just before that, rummaged around in books on the corner, where I bought, among other things, Les Amours de Charles de Gonzague by Giulio Capoceda and printed in Cologne in 1666. There was an old bookplate inside that read, “Per ardua gradior [I forge ahead through adversities].” I underscored my agreement by writing my own, “Tempestatibus maturesco [Storms have made me the man I am].”

Jews were arrested here yesterday for deportation. Parents were separated from their children and wailing could be heard in the streets. Never for a moment may I forget that I am surrounded by unfortunate people who endure the greatest suffering. What kind of human being, what kind of officer, would I be otherwise? This uniform obligates me to provide protection wherever possible. One has the impression that to do that one must, like Don Quixote, confront millions.

Certainly he is horrified by the deportations. But he is also fixed inside his uniform, just as he is fixed inside his love of luxury books. (April 9, 1944: “Reflected on the immense numbers of books lost to the bombings.”) These juxtapositions are sincere, and it’s brave of him to preserve them in this arrangement, but they are also a record of imaginative and intellectual failure.

Maybe the most persistent of Jünger’s limitations is his theorizing about history. These journals are a workshop for a grand theory of the war as an episode in a larger history—a catastrophe of mass culture. In the bloodlands of the Eastern Front in December 1942, he writes, “We find ourselves here in one of those great bone mills that have been familiar since Sebastopol and the Russo-Japanese War. The technology, the world of automatons, must converge with the power of the earth and its ability to suffer in order to give rise to this sort of thing.” Just as a few months earlier in Paris he made this observation: “When surrounded by these crowds, who have renounced free will, I feel more and more alienated, and sometimes it seems as if these people were not even there or that they were merely specious outlines constructed of half-demonic, half-mechanical materials.” The war and its accompanying genocide was, in his opinion, a civil war instigated by the impersonal forces of technology, which had allowed a death instinct to triumph. Everyone, therefore, was a victim—including the German people.

In one way, there’s something admirable about Jünger’s effort to find, however fuzzily, a manner of thinking that might be equal to the facts of mass murder:

The bombardment of Hamburg constitutes the first event of this sort in Europe that defies population statistics. The registry offices are unable to report how many people have lost their lives. The victims died like fish or grasshoppers, outside of history in that primordial zone where there is no accounting.

But it becomes too quickly a shortcut into personal absolution. Jünger was an expert in every variety of ethical swerve. In May 1943 he records a nightmare (the journals are full of his dreams): “Dreamed of being burdened with the corpse of a murdered man without being able to find a place to conceal it.” It’s such a frank depiction of guilt, and of not being able to conceal one’s guilt. But then, in the next sentences, he sidesteps into a glamorously vast historical perspective: “This was connected to the terrible fear that this dream must be of ancient origin and generally widespread. Cain is certainly one of our great progenitors.”

Maybe this is also a problem of the journal as a form. A journal is a monologue that often needs great acrobatic efforts—of playfulness, self-consciousness, the imagining of the self as an other—to transform it into true insight. Too often, it is trapped in theatricality, something orotund and empty: a performance for no one, just an imaginary applauding reader. Jünger’s journals are constantly stalling on inert observations—“The art of getting along with people lies in keeping the same pleasant middle distance over the course of time without becoming estranged, without becoming close, and without a change of quality”—sentences that need to be subjected to the ironies of a novel to achieve any kind of electricity. Everything is staged, artificial, lazy:

La Rochefoucauld: “We find it more difficult to conceal those feelings we have than to affect feelings that we do not have.”

Nego [I disagree]—I think the second is more difficult. This difference of evaluation touched on one of the significant contrasts between the Romance and the Germanic peoples.

What else can a reader do but annotate this with, say, seven amazed question marks?

3.

The image that survives of Jünger from these journals is of the connoisseur of pure spectacle who goes up to the roof of the Hotel Raphael to watch the air raids on Paris: “I hurried up to the roof. The scene presented a display that was both terrifying and magnificent to my eyes.” The most famous version of this repeated scene is his description of an Allied raid on the city on May 27, 1944:

When the second raid came at sunset, I was holding a glass of burgundy with strawberries floating in it. The city, with its red towers and domes, was a place of stupendous beauty, like a calyx that they fly over to accomplish their deadly act of pollination. The whole thing was theater—pure power affirmed and magnified by suffering.

It’s this dedication to style and surface in the midst of destruction that is at once so dazzling and so dispiriting in his writing, and it’s a dedication that finds its final complication in the fallout from the emerging German loss of the war and the failure of the assassination attempt on Hitler. In April 1944 he is on a train from Paris to Germany:

Two young officers from the tank corps sitting by the window…for the last hour they have been talking about murders. One of them and his comrades wanted to do away with a civilian suspected of spying by throwing him into a lake. The other man expressed the opinion that after every time one of our troops is murdered, fifty Frenchmen should be lined up against the wall: “That will put a stop to it.”

I ask myself how this cannibalistic attitude, this utter malice, this lack of empathy for other beings could have spread so quickly, and how we can explain this rapid and general degeneration.

For even here, precisely observing this degraded thinking, he cannot abandon the image of the chevalier:

It is quite possible that such lads are untouched by any shred of Christian morality. Yet one should still be able to expect them to have a feeling in their blood for chivalric life and the military code, or even for ancient Germanic decency and sense of right.

It’s as if he was frozen in a certain attitude and could never abandon it.

In March 1944 Jünger was visited by Lieutenant Colonel Cäsar von Hofacker—the liaison between Carl Heinrich von Stülpnagel and the circle around Claus von Stauffenberg, the instigator of the plot to kill Hitler on July 20, 1944. That evening, Hofacker wrongly informed Stülpnagel that Hitler had been killed, so Stülpnagel—without checking the information—ordered the arrest of more than a thousand SS agents in Paris. A few hours later, it became clear that Hitler had survived. Stülpnagel was ordered to Berlin. On the journey, he shot himself in the head but only managed to blind himself. He was resuscitated and taken to Germany, where he was sentenced to death on August 30. Once again, Jünger’s reaction was the admiring contemplation of a heroically aristocratic image:

I got the terrible news from Neuhaus that yesterday on the way to Berlin, Heinrich von Stülpnagel had put his own pistol to his head. He is still alive, but he has lost his sight. That must have happened at the same hour for which he had invited me to his table for a philosophical discussion. I was moved by the fact that during all the commotion, he actually canceled the meal. That is typical of his character.

It’s true that this attitude might have been partly a deformity of self-censorship, a fear of writing too much. Yet the attitude is too neatly part of a pattern for it to be explained in that way. Months later, back in Germany after the liberation of Paris, Jünger once again repeats his empty idea of chivalry: “They say Montherlant is being harassed. He was still caught up in the notion that chivalrous friendship is possible; now he is being disabused of that idea by louts.”

But maybe the problem in the end was very simple: Jünger was an aesthete who wasn’t a good enough stylist, one too careful to preserve an ideal convention of style rather than dismantle the idea of style completely—and in the process create a new one, absolute and unique. This is why his brief visits to Picasso and Braque in their studios are so revealing and so sad. He admires the art he sees there, but all his descriptive precision disappears. “He is essentially showing us things as yet unseen and unborn,” he writes of Picasso in 1942. A year later, he visits Braque: “The paint was laid on in thick layers of impasto and dripped down like colorful stalactites.” That is all he can manage.

There the true thing was. And he couldn’t see it.