In response to:

How Proslavery Was the Constitution? from the June 6, 2019 issue

To the Editors:

Nicholas Guyatt’s review of my No Property in Man [NYR, June 6] charges that the book isn’t really a work of history at all but, at bottom, a political polemic disguised as history, an act of projection aimed at Bernie Sanders and Guyatt’s own “younger generation of scholars.”

I can only conjecture why Guyatt, a former student in my Princeton graduate seminar, felt compelled to defame my professional integrity. On the level of historical scholarship, Guyatt’s constant distortion of the book’s evidence and contentions betrays a peculiar confusion in which historical dogma and its imperatives prevail over facts and reason.

At every turn, Guyatt either garbles or corrupts my arguments. According to him, the book makes a “case for an antislavery Founding” and advances “a form of antislavery originalism.” It does neither. According to him, the book offers the “familiar” apology that without “sweeping concessions” to slavery there would have been no Constitution; and he says I think that, in his words, “we weaken our politics when we argue that the Founders protected slavery.” But the first claim is false and the second fabricated, the exact opposite of what I think.

Guyatt suppresses my main argument. He says my book recognizes the framers’ proslavery concessions but invents an antislavery founding anyway. On the contrary, I attempt “to move beyond what has become a sterile debate among historians over whether the Constitution was antislavery or proslavery.” The surviving sources show that the Constitution was both. The concessions to the slaveholders helped secure slavery where it already existed while leaving open its expansion. Yet by emphatically refusing to acknowledge the legitimacy of slavery—or, as the phrase went, “property in man”—the Constitutional Convention excluded slavery from national law.

While the framers would perforce tolerate state laws recognizing slavery, they would not enshrine slavery as an institution immune to federal restriction. The majority at the Constitutional Convention upheld this view on matters ranging from the privileges and immunities clause to the abolition of the Atlantic slave trade.

These facts form the heart of my book. Guyatt ignores them. Instead he fixates on a single powerful quotation from James Madison and on the chance that Madison may not have spoken those words, or those exact words, in the convention debate. Petty squabbles aside, it’s not as if my case rests on one remark.

Guyatt ignores the delegate Elbridge Gerry’s declaration that the convention should have “nothing to do with the conduct of the States as to Slaves, but ought to be careful not to give any sanction to it.” Likewise, the convention’s repudiation of a proslavery proposal that, Madison recorded, “seemed to wish some provision should be included in favor of property in slaves.” Likewise, the convention majority’s other painstaking efforts to remove any implication that “slavery was legal in a moral view.” Guyatt apparently thinks he can disprove an argument by disregarding the evidence behind it.

Guyatt gives his game away when he repeatedly twists my actual conclusion into an absurd claim that the framers deliberately slipped in antislavery language for later generations to use. The convention majority was not clairvoyant. It just wanted to limit slavery’s legitimacy under the new national government. Some antislavery delegates said those limits were sufficiently strong that, as James Wilson averred, they would soon lead to “banishing slavery out of this country.” Proslavery delegates elided the exclusion of property in man and proclaimed that the Constitution gave slavery iron-clad protection.

The struggle over slavery and the Constitution was there from the beginning. But that negates the doctrine according to William Lloyd Garrison to which Guyatt clings, a sectarian doctrine the majority of abolitionists rejected, insisting that there was no real struggle, no antislavery inflection; and that the framers simply forged a diabolical “covenant with death”—facts to the contrary be damned.

Guyatt alleges that my book has no room for anyone outside “white elites,” and that it dismisses “a whole field” of fugitive slaves and grassroots activists. In fact, the book describes a crucial part of the antislavery struggle in which white lawmakers, prominent and obscure, were of principal importance, but where activists, including Frederick Douglass, repeatedly played a vital role.

Neither does the book deny that under the Constitution, slavery “did incalculable damage to African-Americans, while hugely increasing the wealth of white people,” including Northerners. Guyatt knows very well that my view of slavery and the antislavery movement embraces and emphasizes everything he mentions, and that my book relates directly to that larger history. On a mission to trash No Property in Man, he pretends otherwise.

Guyatt winds up his review by obliterating the remainder of the historical record. After snubbing the evidence from 1787, he claims political abolitionists of the 1850s “creatively refashioned the founding story for their own ends.” That is, Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass were just making it up virtually out of thin air when they said the framers excluded property in man.

Advertisement

Guyatt overlooks the mountain of evidence dating back to 1789, some of it discussed in my book, that shows agitators as well as political leaders, including some of the framers, asserting what Lincoln and Douglass did. Is Guyatt really unacquainted with the foundational writings of Rufus King, Theodore Dwight Weld, Salmon P. Chase, and their predecessors? Guyatt achieves his dogmatic airbrushing the same way he denies the evidence from the Constitutional Convention itself, by feigning that the evidence doesn’t exist—only this time, he shuns evidence familiar to any credible scholar in the field. Alternatively, more charitably, he doesn’t know what he’s talking about.

I’ve been looking forward to an intelligent, sharp, and serious debate about No Property in Man. Unfortunately, Guyatt’s review, with its ad hominem attacks, dogmatic factionalism, and historical lesions, apparently has another agenda.

Sean Wilentz

Princeton University

Princeton, New Jersey

To the Editors:

In his review of Sean Wilentz’s No Property in Man, Nicholas Guyatt claims on three separate occasions that Abraham Lincoln and Frederick Douglass concocted an antislavery Constitution out of whole cloth in the 1850s. They did no such thing. Beginning in the early 1790s, antislavery constitutionalists urged Congress to attack slavery “to the full extent of your power.” What power? According to William Lloyd Garrison and Guyatt, it had no power to undermine slavery.

The slave trade clause gave Congress the power to tax every slave imported into the country, to ban the slave trade in United States territory, and to prohibit American ships from participating in the trade, long before 1808. The “needful rules and regulations” clause authorized Congress to ban slavery in the territories. The “republican government” clause allowed Congress to make abolition a condition for admission to the Union. The “exclusive legislation” clause enabled Congress to abolish slavery in Washington, D.C. All of these arguments were fully rehearsed in congressional debates well before the mid-1830s, when Garrison emerged as a national abolitionist leader. In nearly every case the proslavery response was that Congress could not do those things because the Constitution protected slavery as a right of property, to which antislavery advocates responded—quite correctly—that the Constitution did not create a constitutional right of “property in man.”

Between the late 1830s and mid-1840s an explosive burst of intellectual energy pushed antislavery constitutionalism much further. The Fourth Amendment ban on unreasonable seizure, the Fifth Amendment guarantee of due process, the privileges and immunities clause, the Tenth Amendment—all were invoked to weaken the fugitive slave clause, protect the freedom of slaves who rebelled on the high seas, and make it constitutionally impossible for Congress to allow slavery in the territories. In 1839 the abolitionist William Jay warned that if the slave states seceded they would forfeit their constitutional right to recover fugitive slaves, a doctrine that Lincoln invoked twenty years later. John Quincy Adams warned that if the South seceded, the war powers clause of the Constitution empowered the federal government to emancipate slaves to suppress the rebellion, a policy Lincoln embraced shortly after the Civil War began. The most radical theorists pushed antislavery constitutionalism to the logical conclusion that Congress could actually abolish slavery in states where it already existed. The mainstream of antislavery constitutionalism never took that last step, but it went much further than Guyatt realizes.

In 1845, in a startling reaction against this creative burst of antislavery constitutional theorizing and the antislavery politics it spawned, Garrison’s ally Wendell Phillips invented the idea that the Constitution was a proslavery document. Until then only proslavery extremists made that argument. With unintended irony, Guyatt quotes Phillips scoffing at “this new theory of the Anti-Slavery character of the Constitution.” But the theory he dismissed had its origins in the founding era, and was certainly older than Garrison’s. Guyatt praises Garrison for insisting that slavery was a national problem, a position that antislavery politicians repeatedly endorsed long before Garrison arrived on the scene.

Guyatt’s unawareness of this tradition leads him to assume things he cannot document. In the first decades of the republic it was widely held that the slave trade was part of slavery itself and as such under the control of the states. The Constitution’s clause authorizing the federal government to abolish the Atlantic slave trade in 1808 marked a major exception to the “federal consensus” that prevented Congress from interfering with slavery in the states. It was a grant of power to Congress, not a restraint on power it would otherwise have had. This explains why early American abolitionists viewed the slave trade clause as a great antislavery victory.

Advertisement

Wilentz restores the ambiguous political legacy that inevitably follows compromises. By 1800, opponents of slavery were complaining about the advantage the South gained from the three-fifths clause. But without that clause the South would have had more power in the House of Representatives and the Electoral College. That’s why, beginning in the 1830s, radical antislavery constitutionalists argued that the clause was an incentive to the states to abolish slavery and a punishment for those that did not. That’s also why, by the 1850s, proslavery Southerners were calling for the repeal of the three-fifths clause. Guyatt, or Wilentz, or I might agree or disagree about all or parts of the antislavery interpretation of the Constitution, but it is untenable to claim that until Lincoln dreamed it up in the 1850s there was no such thing as antislavery constitutionalism. It was, from the nation’s founding, the mainstream position of the majority of Northerners—at least as measured by their votes and speeches in the House of Representatives.

Antislavery constitutionalism enabled thousands of men and women, black and white, all across the North, to claim that fugitive slaves should be afforded the rights of due process, that blacks in Northern states were entitled to the presumption of freedom and the privileges and immunities of citizens. Those who struggled against slavery and racial injustice relied heavily on the foundational precept of antislavery constitutionalism—that the promise of fundamental human equality was embodied in the Constitution and affirmed in its Preamble. Guyatt claims that Wilentz leaves no space for such struggles when that is precisely the space No Property in Man has revealed.

James Oakes

CUNY Graduate Center

New York City

Nicholas Guyatt replies:

I agree with James Oakes that a seam of “antislavery constitutionalism” dates back to the 1790s and refer to this in the final paragraph of my review. Where we may disagree is on the extent of its influence before the 1850s in the face of the Constitution’s bracingly clear provisions. From the futile 1790 debate in the House of Representatives on whether Congress could consider petitions to abolish slavery, through the political bounty offered the South by the three-fifths rule, to the Dred Scott decision of 1857, which denied black citizenship and the right of the federal government to restrict slavery, proslavery clauses and readings of the Constitution consolidated and greatly expanded the reach of slaveholders.

Congress was able to abolish the external slave trade in 1808—with the help of upper Southern slaveholders who expected the value of their slaves to rise as a consequence—but legislators and reformers could not prevent the spread of slavery across most of the continent or loosen the grip of slaveholders on national politics. For the abolitionist Wendell Phillips, writing before the late flowering of antislavery constitutionalism in the 1850s, the harshness of these facts was incontestable: Americans should “take the Constitution to be what the Courts and Nation allow that it is,” Phillips wrote in 1847, “and leave the hair-splitters and cob-web spinners to amuse themselves at their leisure.”

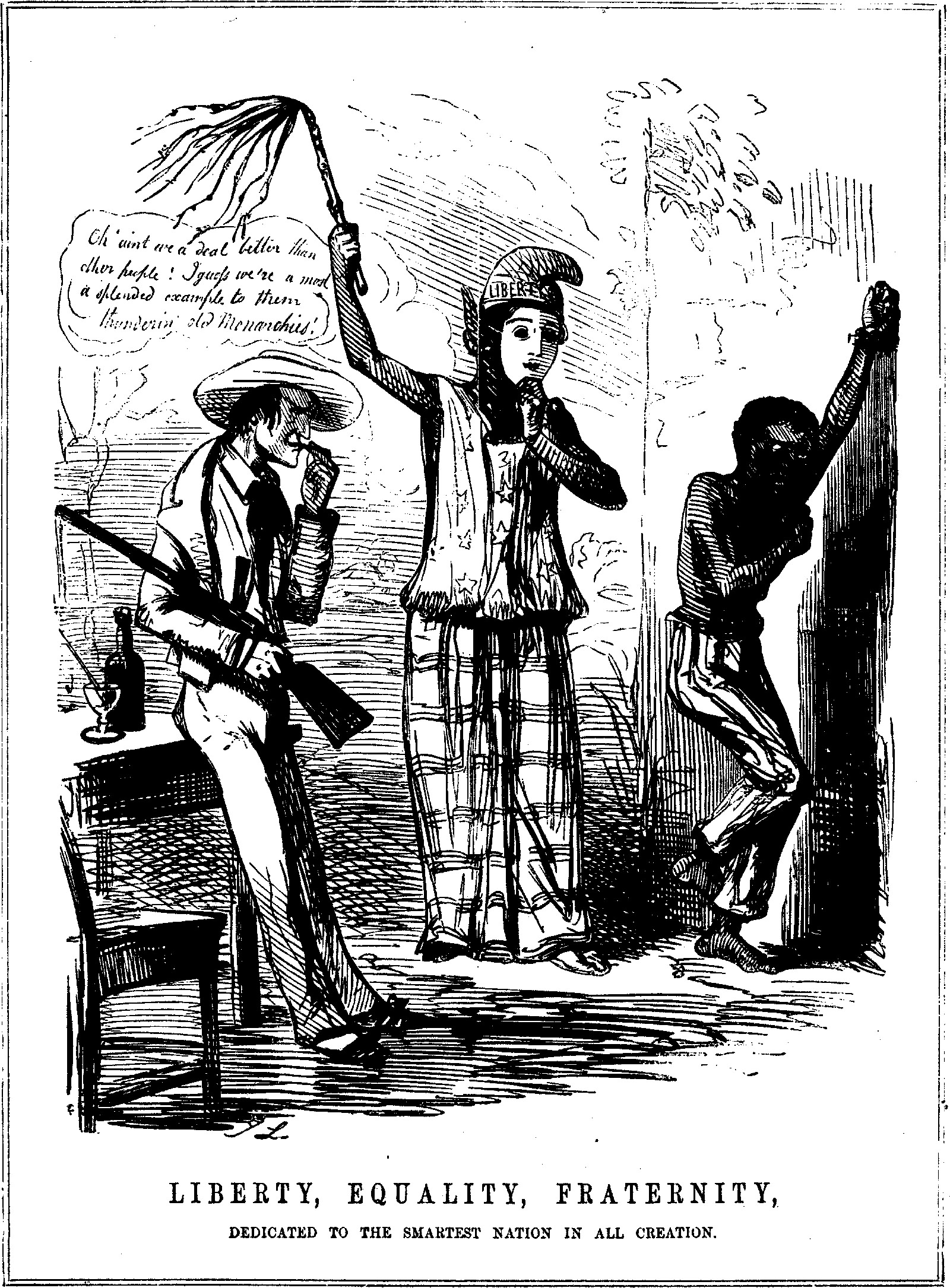

Sean Wilentz reminds us of his intention “to move beyond what has become a sterile debate among historians over whether the Constitution was antislavery or proslavery.” Most historians of the early United States would find this issue neither sterile nor worthy of much debate: the Constitution was plainly proslavery, a fact evidenced by the huge increase in the enslaved population from 1789 to 1860, and by the sprawling territories conquered for slavery over that period. To suggest that the Constitution was both antislavery and proslavery, or to triangulate (as Professor Wilentz does in his book) by insisting that the question of slavery and the Constitution was a “paradox,” is to overstate the antislavery intentions of the Founders and to understate the effects of their compromises.

Certainly the Constitution might have been even more proslavery than it was. At Philadelphia in 1787, delegates from states that had already outlawed slavery (or were contemplating emancipation) rejected language that might have universalized slaveholding throughout the nation. Many felt the pang of conscience; some may have assumed that slavery would expire on its own. But they agreed to a series of concessions that allowed the institution to do untold damage over the next seventy-five years. As Michael Klarman writes in The Framers’ Coup (2016), his history of the Constitution, the most likely explanation for the proslavery character of the document is the simplest one: “southern delegates generally were more intent upon protecting slavery than northern delegates were upon undermining it.”