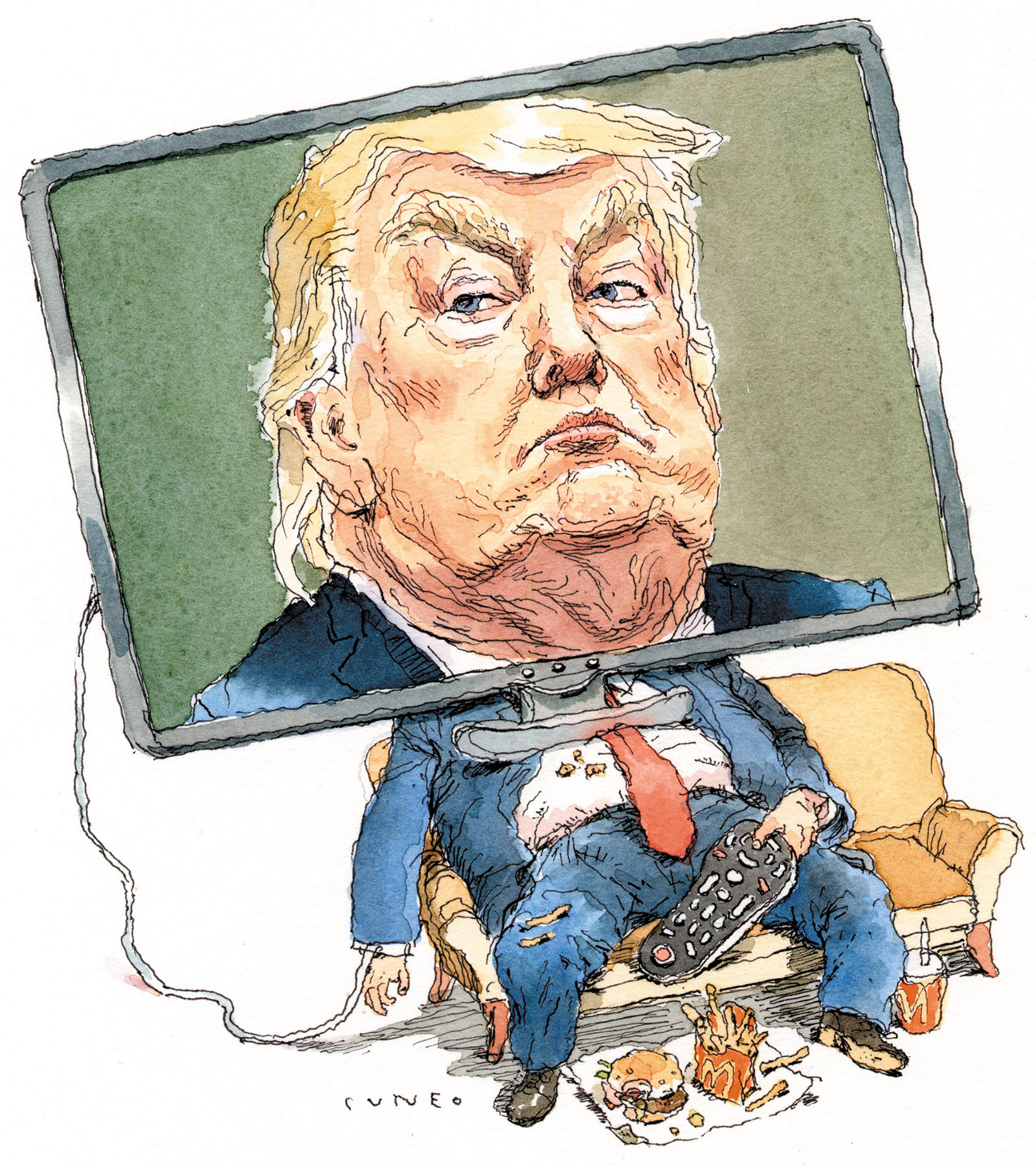

James Poniewozik is the chief television critic of The New York Times, and his new book, Audience of One, tells a double story: the rise of Donald Trump and the rise of television. Poniewozik wants to show us that TV has everything to do with the formation of Trump’s character—his manners, his place in the commercial culture, his ability to track and manipulate popular sentiment and opinion. It seems a reasonable hypothesis. How good is the evidence?

Trump entered the presidency, says Poniewozik, backed by “a four-decades-long TV performance.” That is not quite true. During the first two of those decades, Trump was mainly a creature of the tabloids and celebrity magazines; occasional appearances on TV may have helped, but were not the main event. Television facilitated his passage from tabloids to politics, with a starring role in The Apprentice and Celebrity Apprentice—a survivor show that looked like a quiz show. All the while, of course, Trump was famous as a real estate billionaire in the post-Reagan era when “lifestyles of the rich and famous” were a favorite subject. Anyway, TV-and-Trump is the argument here. They are said to march together more inevitably than, say, Reagan and movies or FDR and radio. We are meant to acknowledge a pairing as inseparable as P.T. Barnum and the circus.

Audience of One slugs this story pretty hard, with sentences like “Donald Trump and TV would grow up together” and “TV was mother’s milk to Trump.” The functional clichés are symptoms of a small but persistent vice of style. When Poniewozik wants to impress the reader more than the evidence warrants, he talks fancy. So he refers, early on, to Trump’s mother’s “lofted nimbus of hair.” His opening chapter, which argues for the all-importance of the medium itself in an age of mass reproduction, abounds with almost-aphorisms such as “Television is the business of ubiquity.” With the broadcast of baseball games on TV, “Suddenly there isn’t just one Yankee Stadium. Now [in Trump’s toddler years] there are tens of thousands—eventually there will be millions.” In those same years, the heyday of popular preachers like Bishop Sheen and Billy Graham, “television became a kind of church itself.” The deep-contextual explanations of Trump have an air of slightly forced wonder.

Television in the 1950s found Trump on the verge of puberty, a crucial period of maturation, which, Poniewozik tells us, corresponded to the release of the Walt Disney miniseries Davy Crockett (1954–1955). He thinks Davy Crockett “demonized American Indians” and had lasting effects “not unlike the toxic racial imagery Donald Trump would later campaign and govern with.” A good many similar points are midwifed by the compulsion to run the history of TV on a parallel track with the education of Trump. Poniewozik says of Playboy—which Trump may have picked up in military school—that the magazine was “Father Knows Best, but with a little something on the side for father.” Actually, an original thing about Playboy was its complete indifference to family. In the Hefner fantasy world, there were no fathers and no mothers, and the girl-next-door centerfold wasn’t anybody’s sister. This marked a serious discontinuity with what came before in popular culture.

The misreadings start to add up when Poniewozik says of the rags-to-riches yokels in The Beverly Hillbillies that they resented the “snooty neighbors” who “looked down on them,” and he goes on to suggest that the Clampett family were the prototype of Trump voters: they bore in silent outrage the scars of “the shared grievance that they were laughed at, scorned as ‘deplorables.’” Well, the show was silly, but its governing conceit was the perfect good nature of the Clampetts: they were always cheerful, obtuse but eager to learn the mannerly ways of their LA neighbors; and the oil money helped. The butts of the comedy were the California natives, all those bankers, social climbers, half-millionaires-on-the-make who fell over themselves in flattery and wheedling. The point about the hillbillies was not their bitterness but their aplomb.

Poniewozik’s chapters on early television grow more credible as they approach his own childhood years as a TV watcher. He is right to say that a relentless pride in wealth, purveyed on shows like Dallas and Dynasty, betokened the coarsening social mood of the Reagan years. Again, it seems fair to name as precursors of Trump’s presidency The Gong Show, The Real World, and Survivor, as well as The Apprentice. Yet the story finally wears thin because Poniewozik can’t refrain from trying to match up his skills as a television critic against the essentially political subject matter: he can hardly name a TV series without discerning the deep structure of the souls of white folk. For example: “Tony Soprano was both an embodiment and a critique of American masculinity”; and many pages later: “Clutching the sides of his debate lectern, [Trump] became Tony Soprano squeezed into the chair of his therapist’s office.” You must have suffered a lot of television for this to be what comes into your mind as you watch Donald Trump at the lectern.

Advertisement

The best pages in Audience of One are given to a description and analysis of The Apprentice. “The homily” offered by the host himself, says Poniewozik, was always the heart of the show:

Each week, Trump delivers a bit of canned wisdom that foreshadows the conflicts that will play out in the challenge. “Don’t negotiate with underlings.” “Nobody else is going to fight for you.” “The leader that wants to be popular, that leader is never going to be successful.”

Here indeed is a clue to his presidency. For though Trump is an attention guzzler—he wants an audience to notice him every hour of every day—he has a smaller need than the average politician for wide popularity. An extra skin or protective layer of unconcern goes with his readiness to say or do the abrasive and insulting thing. It was this that most set him apart from his immediate predecessors, Obama and the younger Bush. The numerical minority and electoral majority that lifted him to the presidency seem to have done it partly in response to this trait. He offered a perversely satisfying relief from the soft-sell pandering of American political life.

When Poniewozik writes of “the media culture,” it isn’t clear whether he counts under that description his own newspaper or any other representative of the left-liberal corporate media. For the Rolling Stone political commentator Matt Taibbi, on the other hand, all the news media—with a few online exceptions—are part of a single poisonous and self-reinforcing information ecosystem. Taibbi thinks the Times is blamable for distorted political coverage, over the last three years, of a sort that renders it a nearer neighbor of Fox News than its most loyal readers could possibly imagine. Since Hate Inc. is largely put together from columns of that period—the same is true, to a lesser extent, of Audience of One—we get a view of Taibbi’s discontents with the media as they took root and ramified.

An early and symptomatic document of the Trump media environment, he suggests, was a Times column by Jim Rutenberg, published in the summer of 2016. Rutenberg argued that reporters had a civic duty to repel the unique threat of a Trump presidency; the press should now be “true to the facts…in a way that will stand up to history’s judgment.” Did this mean a surer method had emerged for standing up to history’s judgment than the persistent and energetic pursuit of the truth? Isn’t that what reporters have always cared about and worked to exemplify? Apparently, something else was now demanded. Each dawn of a Trump day, a reporter should waken fully conscious of the call at his or her back: Which side are you on? Anti-Trump journalism achieved an early climax of barely suppressed pathos in the Times headline Taibbi quotes from the morning after the 2016 election: DEMOCRATS, STUDENTS AND FOREIGN ALLIES FACE THE REALITY OF A TRUMP PRESIDENCY.

And the same question has kept returning: Are you on the right side of history? It came up recently, once more, in the leaked “town-hall meeting” at the Times, at which the executive editor, Dean Baquet, declared that, in view of the anticlimax of the Mueller Report, the Times would “have to regroup, and shift resources and emphasis” to deal with racism as its major issue. Subsequent discussion at the same meeting and the publication the following Sunday of the paper’s 1619 issue—the first fruit of many months’ work on a project that “aims to reframe the country’s history” around slavery and its consequences—gave a concrete meaning to the editorial order to regroup.

In the pattern Taibbi describes, this was a typical expression of the ethic that pervades the anti-Trump media. After all, what journalistic imperative requires a collective purpose of grouping or framing? The very idea of framing—like a TV producer’s “thematic” links from episode to episode—may be incompatible with saying what is both true and important. Unless you believe that reality writes its script according to themes and frames, the duty of an honest reporter is to shun precisely the fictive convenience provided by a frame. A journalistic outlet may have a predictable slant in spite of its attempts at impartiality, but it seems odd to wear the prejudice as a badge of honor.

Most days at the Times are felt to warrant (at a rough estimate) between four and six stories with Trump’s name in the headlines. The front page on October 15, for example, in addition to many stories on Syria and Turkey, carried an item on a “gruesome video” that was “played at a meeting of a pro-Trump group over the weekend.” To swell the chorus of follow-up stories on Syria and Turkey, the front section on October 19 added a full half-page exposition and analysis of Trump’s recent visit to Texas—a piece of ordinary political maneuvering that in another administration might have rated six inches or maybe none. All this keeps the pot boiling. We can’t take our eyes off Trump, and besides, the stories are good for business; subscription numbers are going up, and readers feel a mild glow of validation from the energy of disapproval. We can hate Trump with a semi-civilized smirk.

Advertisement

Even by the standard of the tabloids, the decision to assign separate reports on individual tweets (often interesting only for their vulgarity) was a step down in class for both the Times and The Washington Post. The grave-faced attitude toward these presidential squirts and squibs may have encouraged government officials—including James Mattis, a nontrivial case—to confer legal status on them. It is extraordinary that Mattis first encountered in a careless Trump tweet (“We won”) the final decision to withdraw from Syria last December; he took it as a definitive command, and resigned from the cabinet. But is a presidential tweet the equivalent of an executive order? Constitutionally speaking, these are uncharted waters, but the older respectable media, as surely as Fox, have been lured into playing the president’s chaos game. Twitter in the hands of Trump resembles a hot mic in the hands of an intermittently employed standup comic.

The Times is an organ of the educated middle class. The mobilized anti-Trump energies in the two stories mentioned above were preaching to the choir; yet the relevant membership of the choir included all the networks, the cable stations except Fox, and liberal print and online media generally, all of which still look up to the newspaper of record as the index of genuine news. So, if they are told the inscription on Melania’s jacket deserves attention (“I Really Don’t Care, do U?”), they will follow the lead of their journalistic betters, and they will trivialize. As recently as fall 2016, the Times public editor, Liz Spayd, revived an older definition of journalistic conscience when she resisted charges of “false balance” in the paper’s decision to cover Hillary Clinton’s misuse of a private e-mail server. Spayd was fired nine months later. The job she performed as public editor has been eliminated.

Taibbi’s angriest chapter is his best. He calls it “Why Russiagate Is This Generation’s WMD.” He means that the exorbitant claims regarding Trump’s status as a “Russian agent”—claims associated with John Brennan in the intelligence community, Rachel Maddow on TV, Adam Schiff and Mark Warner in Congress, and scores of writers in the print media—have proved to be a symptom of group thinking as misleading as the disinformation sown by Cheney, Bush, and Tony Blair to support the bombing and invasion of Iraq in 2003. Saddam Hussein was an internationally nonthreatening tyrant, and not a maniac bent on nuclear destruction of the United States. Trump is a corrupt businessman, the crony of others in the US and elsewhere who put their self-interest before their country, but he is not a Russian agent.

Poniewozik notices in passing—but Taibbi gets into much sharper focus—the prototype for Trump’s brags and threats in the occupational skills he learned from World Wrestling Entertainment. His 2007 challenge against Vince McMahon, which can be watched on YouTube, leaves no doubt about his showmanship. He threatens McMahon in high astounding terms, and they agree the loser will have his head shaved by the winner. McMahon lost, and Trump (with obvious relish) kept his promise and shaved the loser’s head. “A pure heel,” says Taibbi—quoting the wrestler Daniel Richards and referring to the typecast bad guy in a match—“wants to be booed by everybody.” This is only partly true: the audience at the challenge seems to be at once booing and cheering for Trump, but the difference between the booing and cheering has become peculiarly hard to discern.

When he transferred his WWE experience to party politics, Trump, at home in a no-man’s-land of the instincts, could shrug off the burden of civility. “The campaign press,” says Taibbi,

played the shocked commentator in perfect deadpan, in part because they were genuinely clueless about what they were doing. They never understood that the proper way to “cover” pro wrestling, if you’re being serious, is to not cover it.

They are still playing that part, still covering Trump with an assiduous care they deny to more consequential subjects: climate change, the Greater Middle East wars that continue to be fought by the US, and threats to free speech that emanate from social media giants like Google, Apple, Facebook, and Amazon, as well as from campus censors and Republican state lawmakers.

Rather disarmingly, Taibbi confesses that he is implicated in the bad habits he deplores in Trump and his journalistic haters. “I was the Triumph the Insult Comic Dog of journalism,” he writes: he won an award once for an article on Mike Huckabee called “My Favorite Nut Job,” in which he described Huckabee as a “Christian goofball of the highest order.” Taibbi hasn’t completely discarded that style: in a sentence on the Fox News show Hannity & Colmes, he describes the ineffectual liberal Colmes as a “quivering, asexual ‘safe date’ prototype from the old broadcast era.” Plenty of online columnists, raised on the playground of social media, now affect a similar manner that precludes reasonable discussion, but Taibbi believes the anti-Trump corporate media suffer from a uniformity of style and substance that is just as bad. How did it come about?

Much of the fault, he thinks, arises from the homogeneity of the journalistic milieu. Fifty years ago, a good many newspapermen and -women came from working-class backgrounds. Now, most political journalists have gone to “expensive colleges,” and “literature degrees are common among our kind (I have one).” Telling stories is what these people do, and their lack of political knowledge is atoned for by their shared possession of an attitude. This imparts an unruffled confidence to their judgments and assures their lack of curiosity about stories or angles that others of their group have identified as pointless. “They are on social media day and night,” Taibbi says, and the people they talk to are each other. “They share everything, from pictures of their cats to takes on the North Korean nuclear crisis.”

There is another kind of sharing that Taibbi neglects to mention. They live-tweet speeches and other political events—a practice that itself presents an obstacle to the freedom of thought they espouse. Even if the reactions are different in detail, a certain conformity follows from their having seen each other’s fast takes on social media before a political event is over. The stories may not line up all on one side, but they cluster around reactions to the same details. Focus on this instead of that becomes a necessary part of the takeaway. Diversity of opinion is further constrained by the overlap of consulting experts across the media. Many reporters at the Post, the Times, The Wall Street Journal, and Politico put their views over a second or third time in regular appearances on CNN, MSNBC, PBS, and NPR. Where the reporting was overwrought and credulous to begin with, as it was with Russiagate, this involves a further arbitrary restriction on the range of legitimate opinion.

The cover of Hate Inc. presents a face-off between two familiar media faces, Sean Hannity and Rachel Maddow, both wearing a clenched expression that yields an unexpected resemblance. Hannity and Maddow’s common pursuit, Taibbi says, is to get their rival audiences “literally addicted to hating each other.” He thinks The Daily Show with Jon Stewart was an exception because it ridiculed both parties, but a different judgment is possible there. Comedy news lightens your responsibility for the criminal actions it giggles at. With its assurance that civic courage is chiefly a matter of having the right opinions, it softens your resolve to act against the wrongs it complains of. In the Cheney-Bush and Obama years, the liberal laughter industry suggested that life was too good for politics.

An incidental difference on a minor point affords a clue to the distinct temperaments that created Audience of One and Hate Inc. Taibbi takes the phenomenon of Ross Perot seriously—a point he underlined in a recent column—whereas Poniewozik laughs him off (“more Timex than Rolex”). In 1992 Perot got 19 percent of the vote in a presidential election, and Taibbi believes, with considerable justification, that his wealth and simple solutions foreshadowed the rise of Trump. Sentence for sentence, Poniewozik is the more politic of these journalist-historians, and if one has in mind the academic virtues of scope and proportion, his is the more coherent book. It is weakened by a certain complacency—a refusal to see that the strange and new is actually strange and new—which can muffle perception. By contrast, one comes to rely on Taibbi to point out the way, for example, the studio sets of TV news programs like Meet the Press now resemble the pre-game shows for NFL football.

He might have added the CNN countdown that precedes, by as much as forty-eight hours, a speech by a political celebrity. Or the officious request for a show of hands on this or that major issue by a slew of docile presidential hopefuls. The media today occupy the same world as politicians, and that is a problem. At any given moment, it may be a puzzle to decide who is calling the tune. In the hour-and-a-half speech in defiance of impeachment and Congress that Trump delivered on October 10 at the Minneapolis Target Center, he asked the cheering thousands on the scene to join him in a memory of Election Day 2016. It was, he said, “one of the greatest evenings in the history of this country,” but a few sentences earlier he had paid it a higher compliment: “One of the greatest nights in the history of television.”

This Issue

December 5, 2019

Against Economics

‘I Just Look, and Paint’

Megalo-MoMA