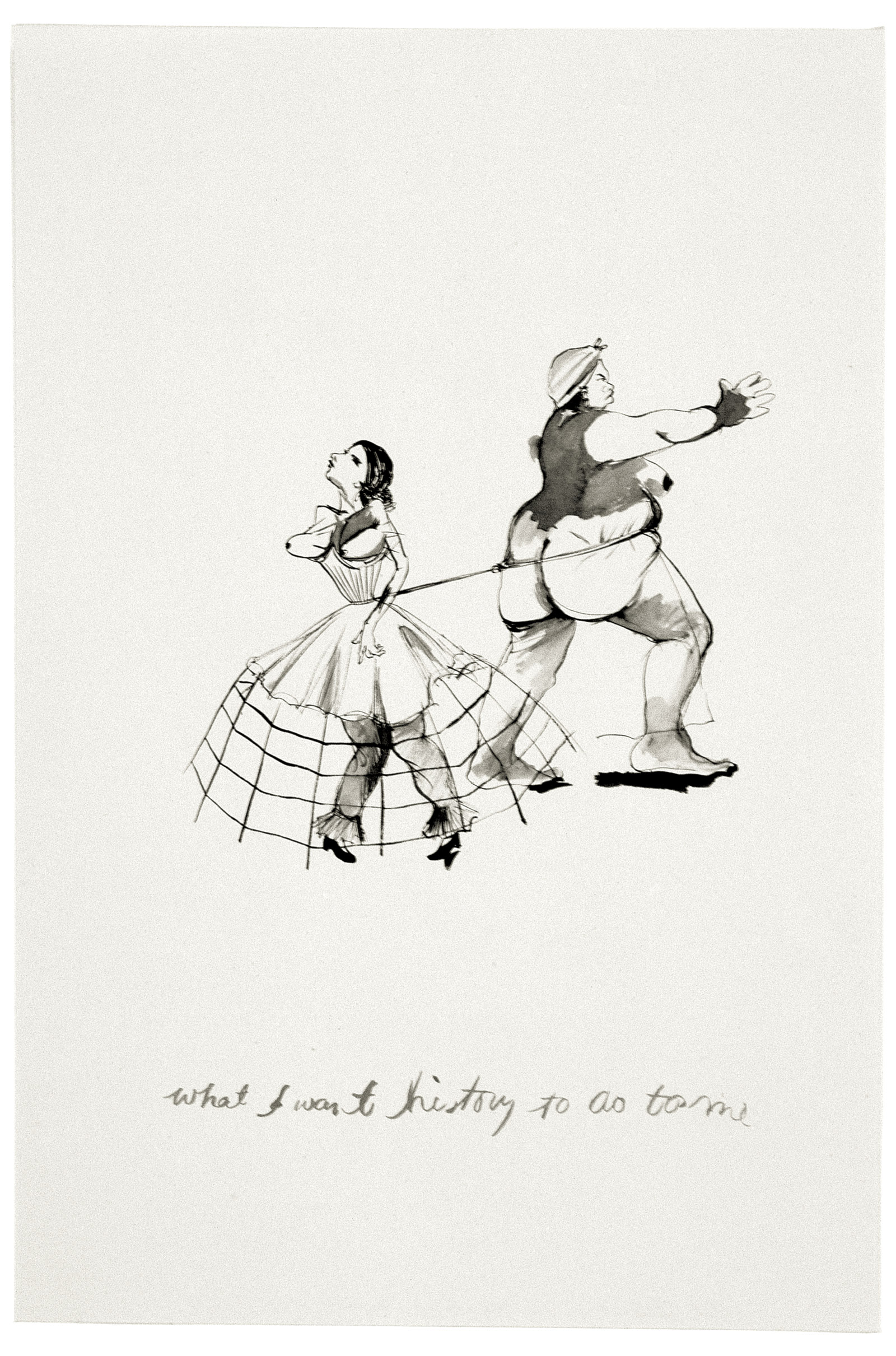

Two women are bound at the waist, tied to each other. One is a slim, white woman, in antebellum underskirt and corset. A Scarlett O’Hara type. She is having the air squeezed out of her by a larger, bare-breasted black woman, who wears a kerchief around her head. To an American audience, I imagine, this black woman could easily read as “Mammy.” To a viewer from the wider diaspora—to a black Briton, say—she is perhaps less likely to invoke the stereotypical placidity of “Mammy,” hewing closer to the fury of her mythological opposite, the legendary Nanny of the Maroons: escaped slave, leader of peoples. Her hand is held up forcefully, indicating the direction in which she is determined to go, but the rope between her and the white woman is pulled taut: both struggle under its constriction. And in this drama of opposing forces, through this brutal dialectic, aspects of each woman’s anatomy are grotesquely eroticized by her adversary: buttocks for the black woman, breasts for her white counterpart. Which raises the question: Who tied this constricting rope? A third party? And, if the struggle continues, will the white woman eventually be extinguished? Will the black woman be free? That is, if the white woman is on the verge of extinguishment at all. Maybe she’s on the verge of something else entirely: definition. That’s why we cinch waists, isn’t it? To achieve definition?

The two women are traced in Kara Walker’s familiar, cartoonish line, which seems to combine in a single gesture the comic brevity of Charles Schulz, the polemical pamphleteering of William Hogarth, and the oneiric revelations of Francisco Goya and Otto Dix. The drawing was made, according to Walker, in “1994ish…when I was 24ish,” which is to say at the very beginning of her career, when her drawings were still largely unknown, and few people knew or could guess at the busy chalk portraits that lurked on the other side of the newly famous—and soon-to-be notorious—paper cutouts. The sentence underneath the image reads: what I want history to do to me. Its meaning is unsettling and unsettled, existing in a gray zone between artist’s statement, perverse confession, and ambivalent desire. The sentence pulls in two directions, giving no slack, tense like the rope. And just as the eye finds no comfortable place to rest in the image—passing from figure to figure seeking resolution, desiring a satisfying end to a story so strikingly begun—so the sentence is partial and in unresolved motion, referring upward to the image, which only then refers us back down to the words, in endless, discomfiting cycle.

What might I want history to do to me? I might want history to reduce my historical antagonist—and increase me. I might ask it to urgently remind me why I’m moving forward, away from history. Or speak to me always of our intimate relation, of the ties that bind—and indelibly link—my history and me. I could want history to tell me that my future is tied to my past, whether I want it to be or not. Or ask it to promise me that my future will be revenge upon my past. Or warn me that the past is not erased by this revenge. Or suggest to me that brutal oppression implicates the oppressors, who are in turn brutalized by their own acts of oppression. Or argue that an oppressor can believe herself to be an oppressor only within a system in which she herself has been oppressed. I might want history to show me that slaves and masters are bound at the hip. That they internalize each other. That we hate what we most desire. That we desire what we most hate. That we create oppositions—black white male female fat thin beautiful ugly virgin whore—in order to provide definition to ourselves by contrast. I might want history to convince me that although some identities are chosen, many others are forced. Or that no identities are chosen. Or that all identities are chosen. That I feed history. That history feeds me. That we starve each other. All of these things. None of them. All of them in an unholy mix of the true and the false…

What I want history to do to me predates Kara Walker’s forays into public art by many years,1 yet in it we can find the problems with which all public art—all monuments, all visual interventions into our public space—must ultimately wrestle. What do we want our public art to do? The official answer is, usually, “memorialize.” We want our monuments to help us commemorate what has passed: our glories, our sufferings. Yet if you grow up, as Walker did, in the shadow of Stone Mountain, Georgia’s monumental tribute to the “heroes of the Confederacy”—carved into the sheer rock and looming over the majority-black population—you will have many questions. Monument to whom? To what? To whose history? To which memories?

Advertisement

Public art claiming to represent our collective memory is just as often a work of historical erasure and political manipulation. It is just as often the violent inscription of myth over truth, a form of “over-writing”—one story overlaid and thus obscuring another—modeled in three dimensions. In the United States, we speak of this. Discussions of power and erasure as they relate to monuments are by now well under way. The astonishing, ongoing absence of public markers of the slave trade, for example—of landing sites and auction blocks, of lynchings and massacres—is a matter of frequent public discussion, debate, and (partial) correction, albeit four hundred years after the first enslaved peoples landed on American shores. In the UK, meanwhile, we have to speak not simply of erasure but of something closer to perfect oblivion. It is no exaggeration to say that the only thing I ever learned about slavery during my British education was that “we” ended it. Even more extraordinary to me now is how many second-generation Caribbean kids in the UK grew up, in the 1970s and 1980s, with the bizarre notion that our families were somehow native to “the islands,” had always been there, even as we pored over the history of “American slavery.”2

The schools were silent; the streets deceptive. The streets were full of monuments to the glorious, imperial, wealthy past, and no explanation whatsoever of the roots and sources of that empire-building wealth. The English side of my own family lived in Brighton, but when we visited I had no clue that those gorgeous Georgian rows of houses, glistening white, had slave sugar as their foundation. “What you leave behind is not what is engraved in stone monuments, but what is woven into the lives of others.” This ancient piece of Periclean common sense gets short shrift in England, where grand monuments to imagined past glories are far preferred to (usually much less glorious) accounts of historical reality. Between official memory and the subjective experience of millions, then, there was a chasm.

Take, for example, the Victoria Memorial, that marble white magnificence in front of Buckingham Palace, with which Walker’s latest piece of public art, Fons Americanus, a huge fountain installed in the Turbine Hall at Tate Modern, is evidently in discussion. As with so many British monuments, what appears to be an act of public storytelling is as least as much about silence as narrative. The self-conceived values of empire are confidently displayed, in the forms of classical figures embodying Peace, Progress, Manufacture, and Agriculture (represented by a woman in peasant dress with a sickle and a sheaf of corn; more to the point would be a black woman holding a stalk of sugarcane with a kerchief round her head). Cherubs abound, and mermaids and mermen and a hippogriff—symbolizing the nation’s nautical domination—but there is of course no representation of the peoples thus subdued by this famed maritime strength, and no tourist standing before this memorial would have any idea that a portion of the money used to build it was in fact raised by West African tribes, who sent goods to be sold, the proceeds of which went to the memorial’s fund. (The people of New Zealand, who also contributed to the fund, are acknowledged in an inscription upon the base.)

How did these West African goods get to London? On the ships of Alfred Lewis Jones—the subject of a few monuments himself—an eminent Victorian shipowner and businessman, remembered, in England, as the “Uncrowned King of West Africa” for his myriad business interests on those shores. In the Congo, meanwhile, he made his mark as Liverpool’s consular representative of King Leopold II of Belgium, and therefore as an apologist and enabler of one of the most brutal colonial enterprises in history, the infamous regime that established the common practice of limb removal by machete. (An abject fact that never fails to come to mind whenever I see Walker’s cutouts of black hands, severed from their bodies, bouncing around a white wall, or falling out of a traditional Mousgoum hut, like a return of the repressed…)

Anyway, into this strange national historical amnesia enters Kara Walker. What lessons can she have taken from her American public art experiences? In the process of making her truly monumental A Subtlety, or the Marvelous Sugar Baby (2014), at the Domino Sugar Factory in Brooklyn, she began, as she often does, with free association, mining both her own mind and our collective consciousness for the many sweet and sour resonances of sugar: “Starting with sugar and molasses, and molasses is a byproduct of the sugar processing.” And then asking herself: “What other byproducts are there?” Walker’s historical researches are never superficial, and her art practice has always included an almost equal amount of reading and writing, from which the visuals emerge. Researching sugar, she found herself once again neck-deep in blood and horror. Slave labor, colonization, land seizure, extractive capitalism, the exploitation of women and children, and then, later, the global cultivation of sugar addiction, a public health catastrophe that can be said to affect most profoundly the black and the poor. “And I got to the end and I was like Ruins!… Ruins!… And I couldn’t just produce ruins.”

Advertisement

What is the correct response to a ruinous history? What, if anything, is the artist’s “duty” here? Should ruins always and everywhere be “reclaimed”? Should ruins be consciously rebuilt into something “positive”? If not the representation of ruins, then what? Walker:

Up until that point I had been thinking of finger-wagging doom-laden things about the history of slavery and sugar and America. It didn’t take into account what people wanted to look at. When I came up with the idea and made it, it reminded me of wanting to do the cut-outs, that sense of giving people something they wanted to look at, working with their attention span in a way.3

Walker’s particular mode of engaging with our attention spans—her visual and conceptual provocations—have often caused furor, first from the generation above her, now not infrequently from the generation below. For when it comes to the ruins of history, Walker neither simply represents nor reclaims. Instead she eroticizes, aestheticizes, fetishizes, and dramatizes. With the consequence that she is accused of an unnecessary or inappropriate cultivation of the grotesque, of a prurient interest: “salaciousness.” As if Walker’s manner of aestheticizing ruin, so that our attention may be kept upon it, was a unique scandal in the history of art (or, at least, as if no black woman artist had a right to take up the tools Walker assumes as her inheritance and her right).

But this mode of relating to the ruins of the past is hardly without precedent. Approaching Walker’s Sugar Baby that summer in Brooklyn, first one passed a series of melting child figures, dripping molasses, holding in their arms or on their backs the kind of baskets field laborers use. They looked like those heartbreaking child “blackamoors” you spot in the corners of eighteenth-century paintings, carrying sweet delights for the pleasure of Milady. (Though to me they were the very picture of the Liberian child laborers I once saw tapping hot gum out of the trees, intended for the American tire market.) But there was an older echo, too: in their arrangement, lining the path to the main event—to the Sugar Baby herself—they recalled the Stations of the Cross, one of the most familiar sequences in Western art, the culmination of which is the crucified Christ. Like Walker’s Sugar Baby, he is usually oversized, at the back of a long room, and we approach him, as we approached her, as a figure of worship, a subject of pity, of mournful contemplation, of sadomasochistic erotic interest, not to mention as the embodiment of an infamous historical crime.4 All over Europe, in church after church, we encounter the same fascinating admixture of the sexual, the sadistic, and the sacred. The real scandal in the Domino factory, perhaps, was the identity of the object thus occupying our attention: not white and male but black and female.

If we had to choose an ur-Walker image—the one that comes to mind when we think of the artist—it would be Slavery! Slavery! (1997), shown in her blockbuster gallery show “My Complement, My Enemy, My Oppressor, My Love” in 2007–2008. The images themselves—violent, scatological, sexual, hateful, loving—exist in an unholy mix, like the show’s title. They are given no hierarchy, moral or otherwise. All elements are presented simultaneously.

It was this early work that famously prompted the older artist Betye Saar to label the young Walker “a black artist who obviously hated being black,” whose work was for the “amusement and the investment of the white art establishment.”5 Two statements that represent a terrific double bind—a rope thrown by one black woman to constrict another, that surely ends up constricting them both. (In 2019 MoMA, certainly a temple of the “white art establishment,” bought forty-two drawings by Saar and celebrated her with a hugely successful solo show.) Such condemnations amount to an all-too-familiar injunction, directed at minority artists perennially and in all mediums. Your success, runs the argument, can only mean you are “playing up to” or “displaying our dirty laundry in front of” the majority audience. (The implication being: What else could account for it? Itself a sly depredation.) Under this logic, you are either unconsciously giving “them” what they want (self-hatred) or you are consciously doing so (self-and-community-betrayal). That the black artist might be following their own nose—pursuing their own preoccupations and obsessions—is here given no credence. The white viewer, in these debates, is really the only thing on a black artist’s mind.

More recently, the injunction has taken on a new flavor: now work is condemned for being insufficiently empowering, stuck in a regressive negative, neglecting to provide, for a black audience, some necessary form of “self-care,” which is considered especially vital now, during this desperate political moment. But uplift is not the only role of black art. It is possible to both admire the witty and righteous reclaiming of caricatures—like that of Saar’s excellent own The Liberation of Aunt Jemima (1972)—as well as the more recent, idealized, “positive” black stereotypes of queenly black women presented by Simone Leigh, and still urgently desire to stand enclosed in a Walker diorama (which, in my experience, includes few “amused” viewers, white or otherwise).

Walker operates on the premise that when you make history truly visible, both your own and that of your people or nation, there exists a challenge to show all of it, the unholy mix, the conscious knowledge and the subconscious reaction, the traumatic history and the trauma it has created, the unprocessed and the unprocessable. If you manage this it will be, by definition, de trop. But then again, too much for whom? The very idea that Slavery! Slavery! is an exaggerated or extreme or unnecessarily salacious image is to me strange, given the history through which it consciously tumbles.

Consider, for example, the case of one Thomas Thistlewood. Thistlewood was from Lincolnshire, England. He died in 1786, forty-seven years before Britain’s Slavery Abolition Act was passed in 1833. There are no monuments to him in England, but he is notorious, among Jamaicans, for his 14,000-page diary, documenting his time as a plantation owner on our island. A lower-middle-class man, he was an autodidact, and the recto pages of his diary are filled with a meticulous account of his enlightened interest in medicine, horticulture, religion, political theory, and much else. The other half—the verso pages—records the 3,852 acts of sex he had with his slaves, and the regular vicious punishments he doled out to them, baroque in their sadism and perversion. Once, after a particular slave had run away and been caught, Thistlewood gave him “a mod[erate whipping], pickled him well, made Hector [another slave] shit in his mouth, immediately put in gag whilst his mouth was full & made him wear it 4 or 5 hours.” Apparently pleased with this novel punishment, he repeated it on many others. Often he flogged slaves and then “wash’d and rubb’d [them] in salt pickle, lime juice & bird pepper.” To punish the aforementioned Hector for losing a hoe, he whipped him and then “made New Negroe Joe piss in his eyes &mouth.” In addition to forcing men, women, and children into the backbreaking work of cutting sugarcane, sometimes he used a byproduct of sugar for the purposes of torture: “Put him in the Bilboes both feet; gagged him; locked his hands together; rubbed him with Molasses and exposed him naked to the flys all day, and to the mosquitoes all night.”6

Lest it be thought Thistlewood was a lone sociopath, his diary reveals how he was often allowed to rape the slaves of neighboring overseers and let them rape his slaves in exchange. And, through it all, Thistlewood maintained an intimate, thirty-three-year relationship with a slave called Phibbah, with whom he had his only son, “Mulatto John.” They were apparently warm and affectionate with each other, Phibbah and Thomas. Once, Thomas brutally flogged his son for refusing to work. Once, Thistlewood found one of his slavedrivers, Johnnie, in competition with Thistlewood’s own visiting nephew—they were both in the habit of raping the same slave, “Little Mimber”—and so Thistlewood warned his nephew off and then viciously beat Little Mimber as punishment. Once, a fellow plantation owner sent Thistlewood the head of a runaway slave as a present and Thistlewood put it on a pole on his estate so that all might see it. In his will, Thistlewood called Phibbah his “wife,” freed her, and left her money and two of his own slaves.

What is the correct artistic response to history like that? Which aspects should be obscured or tidied away or carefully contextualized to protect the viewer’s sensibility? In what relation do we stand to our ancestors if we insist we cannot now even stand to hear or see what they themselves had no choice but to live through? Is not the least we owe the sufferings of the past a full and frank accounting of them? The word “salacious” withers before the historical truth. Salacious: having or conveying undue or inappropriate interest in sexual matters. What is the appropriate level of interest in the interrelation of sex and violence in our history?

Caricature and stereotype are not Walker’s flaws—they are her sharpest tools. She treats them as the DNA of history, the building blocks of our social reality, “scripting” for us, informing and affecting our behavior, and posing the greatest risk not when they are made explicit but rather when they are allowed to sink into invisibility, to appear “natural” or “inevitable.” It is then that they become most firmly entrenched as ideology. It’s then that we find ourselves abiding by them unconsciously, without knowing why. “I have always responded,” Walker has said, “to art which jarred the senses and made one aware physically and emotionally of the shifting terrain on which we rest our beliefs.”7

A striking example of this came in 1998, when Walker traveled to Austria, answering a commission to create a “safety curtain” for the Vienna State Opera. The results were manifestly unsafe. Allowing, once again, for free association without self-edits or self-consciousness, Walker wickedly conjured the Austrian African Imaginary: little black “Turks” in fezzes holding out cups of coffee, with gold rings in their ears and Aladdin shoes; dancing girls in grass skirts, in banana skirts, stark naked, the whole exotic black Kabaret; black bodies inscribed into academic zoological studies, or placed in actual zoos, or made out of porcelain, eternally holding out an ashtray or a serving dish, or sweating underneath paladins carrying Arab kings, or cooling European royalty with those huge feather fans…

In Safety Curtain, the monograph that accompanied her Austrian experiment, she places, in the same visual frame, a shocking nineteenth-century physiological illustration intended to demonstrate the closeness of the black man to an ape, with an equally poisonous contemporary news photo of Mike Tyson, biting the T-shirt of a blond toddler who screams in terror. She offers, too, a “before and after” picture—the type of beauty advertisement still common in the 1990s—in which a childhood picture of Oprah is the “before,” and a blue-eyed blond is the “after.” That is, she makes explicit the logic of so many of our contemporary media images: she reveals their DNA. The animalistic black man. Whiteness as purified blackness. Walker shares Warhol’s genius for caricature and stereotype, and what she has said she admires in his work—“simplicity and [the] strange mute ability to distil a culture into a single image”—we find also in hers. Like Warhol she is never subtle, even when making a “subtlety.” From her “Notes from a Negress Imprisoned in Austria”:

I am and shall continue to be the monster in your closet. Prodding at your tightly wound arsenal, your history.

Let Me Out.

And. You. shall. seek. to. put. me. back. in.

And together we will: in and out and in and out together HAHA!8

Which is to say, images have intercourse with each other—they fuck each other. They’re incestuous. They spawn. And it is when this process is subconscious and invisible that it is most insidious. So much of what was written about Mike Tyson, in the 1990s, had a long and deadly cultural history, and every time we looked at or thought about him, some of that history came along for the ride. Walker sees and makes visible so many of these kinds of historical exchanges, substitutes, echoes, and reoccurrences, but claims no external, objective vantage point on them. “I don’t think that my work is actually effectively dealing with history,” she has said: “I think of my work as subsumed by history or consumed by history.” The difference between Walker and so many of us is that she knows it.

Walker: “When you have monuments or commemorative things that just exist, they sit there and they disappear.” Walker’s monuments never simply sit, they never stand apart from history as something finished or finalized—and they crave movement. Over the years her cutouts have become animated, and her walls have turned circular, dioramic, and even those notorious “amused” white art patrons have found themselves backlit and cast as shadows, implicated and involved in the art they came merely to view.

In 2018 Walker brought her dynamic vision of the past to Algiers Point, New Orleans, once a holding area for slaves. A small, inadequate plaque marks the spot. A steam-powered calliope was Walker’s typically unsubtle intervention, a catastrophic caravan that took the sentimental organ music of the Mississippi and recast it in a monstrous carved box of black steel, through which steam poured and history seeped. To let off steam, as a calliope must do, is visually cathartic, and the music was black resistance and uplift combined: “negro” spirituals, “We Shall Overcome,” “Down by the Riverside,” etc. But the sound each pipe made was somewhere between scream, off-key wail, and—thanks to the huff and puff of the steam itself—a hellish and industrialized machine of torture. The effect was dreadful, in the ancient meaning of that term, and too provoking and active to be called, exactly, a monument. Monuments are complacent; they put a seal upon the past, they release us from dread. For Walker dread is an engine: it prompts us to remember and rightly fear the ruins we shouldn’t want to return to, and don’t wish to re-create—if we’re wise. Dread is surely one of the things we want history to cause in us, lest we forget.

But to talk of Walker’s art this way, as if history were its only concern, and our “opinions” about that history its only content, is to traduce the art itself. Much has been written about Kara Walker, too much—journalistic debates about her often threaten to subsume any real attempt to see this work in all its strangeness.9 (Or to allow it the intimate psychology we simply assume with an artist like, say, Tracey Emin, whose engagement with feminist ideas and feminist art history in no way precludes our noticing the personal.) Walker:

The illusion is that it’s about past events…simply about a particular point in history and nothing else. It’s really part of the ruse that I tend to like to approach the complexities of my own life by distancing myself and finding a parallel in something that’s prettier, more genteel.10

These complexities have included some masochistic sexual relationships, a long romantic history with white men, a mixed-race child, and inconvenient psychic attractions to “heroic” white figures like Scarlett O’Hara in Gone with the Wind that leave her “wanting to be the heroine and yet wanting to kill the heroine at the same time.” In art school she was tormented by the sense that she was “going to put my foot in my mouth if I was honest about my own failings as a black woman,” and in one early interview she recalls a slogan on a popular 1990s T-shirt, It’s a Black thing, You wouldn’t understand: “It inspired a whole way of thinking for me. Because, obviously the ‘you’ in the saying is Not Black…. So what does this mean to the person who is black and still doesn’t quite understand?”

These uncollegiate expressions of failure and incomprehension in Walker’s retellings reveal—like the border between her black cutout edges and her white backgrounds—something significant in the contrast. For of course you can’t fail as a white woman qua white woman; whiteness is not formulated as a test. A white thing is, by definition, whatever a white person does. Whereas blackness is nothing but test. So many things can threaten a black woman’s blackness (in the eyes of white people, black people, herself) that the fear of this threat can constitute an entire shadow identity, if one allows it to do so. The wrong kind of art, the wrong kind of husband, the wrong kinds of interests, the wrong kind of curiosity, the wrong kinds of desires, the wrong kinds of confessions. Confessions like this: “If the work is reprehensible, that work is also me, coming from a reprehensible part of me.”

One gift an artist might give to other artists is a demonstration of how to make work without shame. Without being cowed or terrified by the opinions of others. As Walker’s cousin, the novelist James Hannaham, once said of her, “She has the hermeneutic idea of the role of the artist in society—a person who is strong enough to withstand projection and then can project ideas back to the people in such a way that their minds change. Or not.”11 What kind of shameless black woman imagines a “negro” boy with a hole in his chest through which a bird has just bust through, stealing his heart? Kara Walker. What kind of shameless black woman imagines a little white boy sucking on the tip of an African girl’s banana skirt as the girl also suckles herself? Kara Walker. What kind of shameless black woman imagines rape and chaos while a tiny Abraham Lincoln saunters by? Kara Walker.

The shame is meant to be the shame of being multiple. Of not understanding what the (notably singular) black “thing” is or should be because, in Walker’s work, blackness is so many things:

I was looking at the identity politics of the 1970s and 1980s and thinking the idea of a single identity—the militant black woman, or whatever—wasn’t enough. At any one moment I felt like 13 different characters piecing themselves together. Some of it was coming out of bizarre lived sexual experiences I’d had with people who will go unnamed, some of it was, like, I don’t know, reading Gone with the Wind. The feeling I was left with was that it was probably my job to gather all those pieces back into one room. They were all pieces of me and they were unruly. 12

Into one gigantic space, then, the Turbine Hall at the Tate Modern, Walker now gathers all her pieces. At the time of writing, this work was still in process, and I had access only to drawings and fragments, scraps and ruins and partial models, but I saw a monument rising, a “water feature,” not unlike the Victoria Memorial just down the road, featuring waters that seem to flow directly from the Middle Passage—or else from that dreadful stretch of sea between Libya and Lampedusa, currently swallowing up black people at a terrifying rate. I saw a monument in sketch, surrounded by small boats in trouble, that once again suggested to me not only the old trade in humans but the more recent arrival of African bodies to European shores, no longer slaves but still the desperate subjects of a capitalism red in tooth and claw. That catastrophic caravan of history, circling again.

And atop her fountain, I spotted a typical Walkerian figure of resistance—a spectacular “negress,” spurting water from her nipples—and this reminded me of all her soaring birds smashing through slave bodies—as if the urge for freedom could be animated and embodied—and her magnificent swans, lending their wings to the oppressed, and her flying black cherubs and pig-tailed “Topsys” who can often be seen shooting into the sky, propelling themselves above ruin and chaos. Such repeated figures are the not-so-secret glory hiding in plain sight of so many Walker images, obscured by the endless chatter of journalism about her “salaciousness,” but not unwitnessed by those who have eyes to see. In England, where so many people still consider it bad taste even to mention Britain’s long and complex history with the people of the African diaspora, a Walker monument is a thrilling intervention. I imagine awe at the scale. I imagine accolades and protests. I imagine the usual palaver that Walker has already imagined and described herself:

Students of Color will eye her work suspiciously and exercise their free right to Culturally Annihilate her on social media. Parents will cover the eyes of innocent children. School Teachers will reexamine their art history curricula. Prestigious Academic Societies will withdraw their support, former husbands and former lovers will recoil in abject terror. Critics will shake their heads in bemused silence. Gallery Directors will wring their hands at the sight of throngs of the gallery-curious flooding the pavement outside.13

I hope Walker is never ashamed to be the wrong kind of artist/woman/black person, or ever exhausted by our endless projections upon her. Twenty-five years after she exploded into the art world, I hope it continues to be her self-defined job to gather all the ruins of her own, and our, history—everything abject and beautiful, oppressive and freeing, scatalogical and sexual, holy and unholy—into one place, without attempting perfect alignment, without needing to be seen to be good, so that she might make art from it. And thus stand up for the subconscious, for the unsaid and unsayable, for the historically and personally indigestible, for the unprettified, for the autonomy of an imagination that cannot escape history, and—more than anything else—for black freedom of expression itself.

This Issue

February 27, 2020

Trump’s Show Trial

Can Journalism Be Saved?

-

1

Although, in the case of an artist as instantaneously successful and famous as Walker, there is a sense in which all of the art has been “public.” ↩

-

2

Though, again, not in the classroom. Diaspora education came informally: from one’s parents, from hip-hop, from American movies and books. If, more recently, some burgeoning awareness of Britain’s slave past has entered public consciousness, this is largely thanks to a number of popular works of history, narrative, and cultural analysis produced by black British scholars and artists. Books like Black and British: A Forgotten History by David Olusoga, Andrea Levy’s novel The Long Song, and Natives: Race and Class in the Ruins of Empire by the rapper, writer, and activist Akala, which was a Sunday Times best seller in Britain. ↩

-

3

Interview with Tim Adams, “Kara Walker: ‘There Is a Moment in Life When One Becomes Black,’” The Guardian, September 27, 2015. ↩

-

4

The fundamental peculiarity of this European art practice was long ago pointed out by the late comedian Bill Hicks: “You think when Jesus comes back he’s gonna want to see a fucking cross, man?” ↩

-

5

Betye Saar speaking in an episode of the PBS series I’ll Make Me a World, 1999. Quoted in Thomas McEvilly, “Primitivism in the Works of an Emancipated Negress,” in Kara Walker: My Complement, My Enemy, My Oppressor, My Love, edited by Philippe Vergne (Walker Art Center, 2007). ↩

-

6

From entries for July 23, July 30, and August 1, 1756. Thomas Thistlewood Papers. James Marshall and Marie-Louise Osborn Collection, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University (ISB MSS 176). ↩

-

7

Ariane Grigoteit and Friedhelm Hütte, eds., “Answers and a Little Bit of Wine,” in Kara Walker: Deutsche Bank Collection (Deutsche Bank Art, 2002), p. 7. Quoted in Rebecca Peabody, Consuming Stories: Kara Walker and the Imagining of American Race (University of California Press, 2016), p. 118. ↩

-

8

Kara Walker, “Notes from a Negress Imprisoned in Austria,” in Johannes Schlebrügge, ed., Kara Walker: Safety Curtain (Vienna: P and S Wien, 2000), p. 23. ↩

-

9

And the Walkerverse is passing strange. You think it’s just like nineteenth-century racist caricature until you actually look back at nineteenth-century caricature. Walker’s “negro” caricatures have a graphic language of their own—no cartoon red lips, no rolling eyes—and a distinct demonic glee you don’t find in their antebellum ancestors. They have designs on your subconscious; they mean to march straight off those walls and into your cerebellum, where they will remain, perniciously lodged, along with the brutal history that created them. ↩

-

10

Interview by Susan Sollins, Art:21—Art in the Twenty-First Century, episode 5, season 2, DVD/VHS (PBS, 2003). ↩

-

11

James Hannaham, quoted in Doreen St. Félix, “Kara Walker’s Next Act,” New York Magazine, April 17, 2017. ↩

-

12

Interview with Tim Adams, 2015. ↩

-

13

From the press release for Walker’s exhibition Sikkema Jenkins and Co. is Compelled to present/The most Astounding and Important Painting show/of the fall Art Show viewing season!…, Sikkema Jenkins & Co., New York City, 2017. ↩