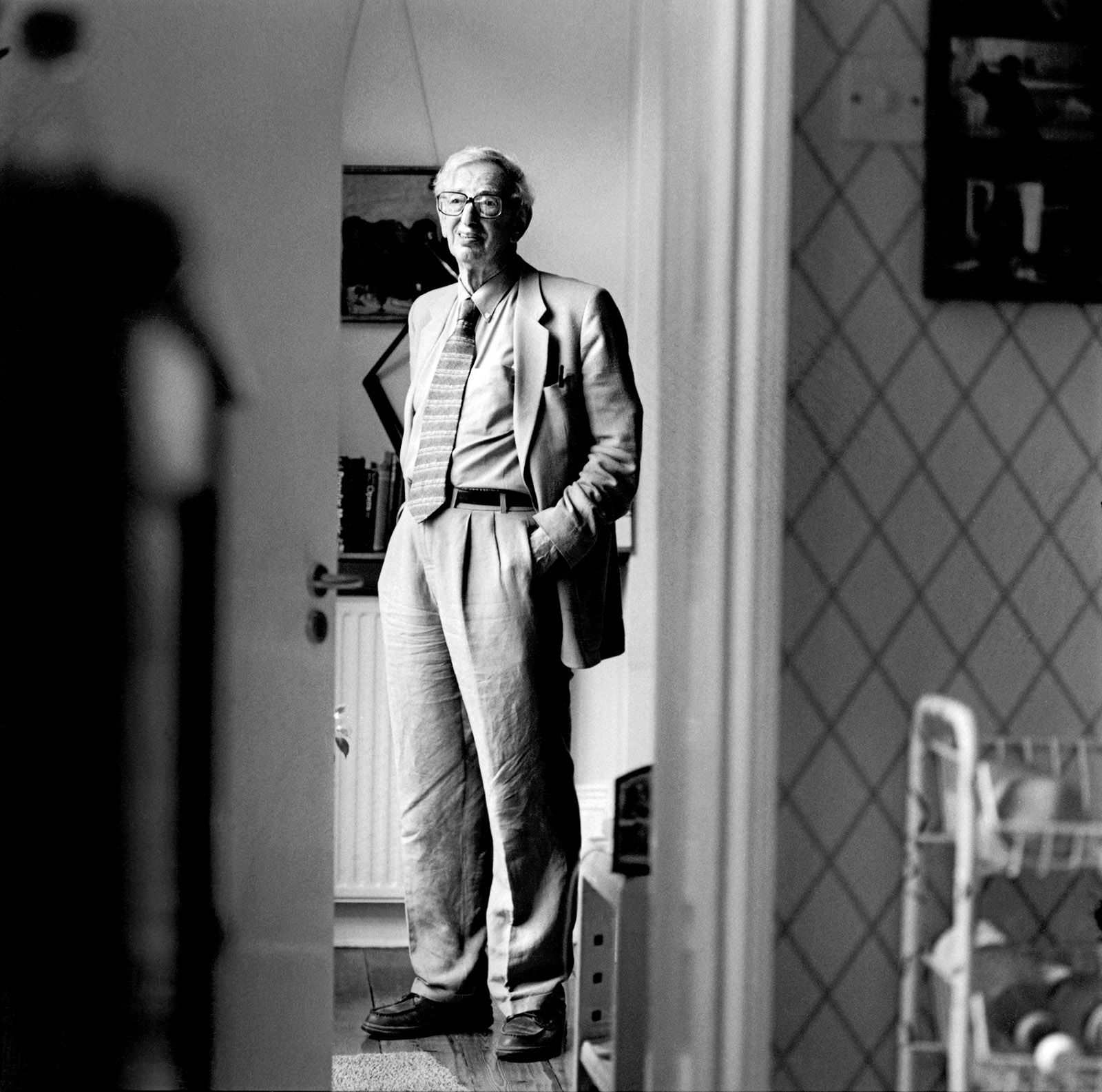

When Eric Hobsbawm died in 2012 at the age of ninety-five, he was probably the best-known historian in the English-speaking world. His books have been translated into every major language (and numerous minor ones), and many of them have remained continuously in print since their first appearance. Though his work centered on the history of labor, he wrote with equal fluency about the crisis of the seventeenth century and the bandits of Eritrea, the standard of living during the industrial revolution and Billie Holiday’s blues. For range and accessibility, there was no one to touch him. What he gave his readers was above all the sense of being intellectually alive, of the sheer excitement of a fresh idea and a bold, unsentimental argument. The works themselves are his memorial. What is there to learn from his biography?

Historians lead for the most part pretty dull lives: if they make it big enough to warrant a biography of their own, it is unlikely to feature anything more exciting than endless conferences, gripes about publishers, and the eventual bestowal of honors. Readers do not generally care about infighting in academia. Nor is it easy to be gripped by the more important but largely abstract questions of intellectual argument and debate that articulate positions and create schools of thought. In Hobsbawm’s case, however, the scale and nature of his achievement raise questions of their own. How do we explain his vast readership? How did a Marxist historian achieve such success during socialism’s decline in the second half of the twentieth century? Richard J. Evans’s detailed, absorbing, and fair-minded biography does not really address these questions, but it gives us the means to do so.

The ingredients were there from the outset to make a historian of great breadth and general appeal. Hobsbawm’s secular Jewish parents belonged to the emancipated generation that embraced the possibilities Europe offered Jews for the first time in their history. Born in Whitechapel, London, in 1881, Hobsbawm’s father, Percy, was an amateur boxer and athlete with no discernible interest in matters of the faith apart from choosing to marry a Jewish woman, Nelly Grün, who came from Vienna and a more well-to-do and cultivated background than Percy.

Eric was born in British-occupied Alexandria in 1917, when Percy was working for the Egyptian Postal and Telegraphic Service. Shortly afterward the family moved to Vienna and Eric’s early years were spent first there and then in Berlin, both cities traumatized by the effects of World War I and the collapse of empire. That he had lived through the rise of Nazism marked Hobsbawm out from most Englishmen of his generation and made him seem like another one of those European Jewish refugees who did so much to shape the postwar British academy. Yet as a subject of King George V, he was known to his Berlin schoolmates at the Prinz-Heinrichs-Gymnasium as “the English boy.” While he grew up bilingual, fluent in English and German, his father’s family had been in England for several generations, and by the time his undergraduate days were over he had probably read more of the classics of English letters than most people manage in a lifetime.

In the large Victorian house on Nassington Road in London, where he and his wife, Marlene, brought up their family, the bookshelves were revealing. The study upstairs was filled with the kind of things one might have expected—specialized monographs, the complete Marx-Engels, the works of Lenin. But downstairs in the living room were the novels, essays, poems, and plays that he had enjoyed for decades. I taught at Birkbeck College, University of London—where Hobsbawm had taught since the 1940s—after his retirement; he retained an office in the department and was an active presence in its intellectual life. After his death I visited Marlene, and while we had tea and talked, I picked up a dog-eared Everyman edition of Sir Thomas Browne’s masterpiece Religio Medici. Inside the front flap was the owner’s scrawled inscription: “Hobsbawm, June 1944. Salisbury.”

The richly sociable life he enjoyed in north London in his final decades, and which Marlene Hobsbawm describes in her affectionate new memoir, represented a sharp contrast to the emotional difficulties of his early years. He was barely twelve when his father died in agony on the family doorstep, carried back from work one day in 1929; the cause of his death appears to have been unknown. It was the first shock in a childhood of gradual impoverishment and emotional isolation. Hobsbawm had always felt closer to his mother, who passed onto him her love of literature and of the English language, which, despite her background, she insisted on speaking at home. Yet tragedy followed tragedy: nine months after her husband’s death, Nelly fell ill with tuberculosis, and she died in 1931, aged thirty-six.

Advertisement

Orphaned, Eric and his younger sister, Nancy, went to stay with their uncle and aunt in Berlin; in 1933 they all moved to England. He was not uncritical about the land of his passport: after Berlin, he wrote, Britain could seem a “terrible let-down”—provincial and boring. But as a Cambridge chum later noted, he “had a large and vulgar patriotism for England, which he considered in weak moments as his spiritual home.” This allegiance peeps out startlingly in some of his works. “We were never defeated in war, still less destroyed,” he writes, with a revealing use of the first-person plural, in a work about the industrial revolution, Industry and Empire.

At St. Marylebone Grammar School for boys Hobsbawm read with almost unbelievable range and intensity, devouring Baudelaire in French; Heine, Hölderlin, and Rilke in German; and contemporary prose from Woolf to Dos Passos and Eliot. The shelves in his bedroom at home contained Shakespeare, Donne, Pound, Keats, Shelley, Milton, and Herbert, as well as Auden and Day Lewis. In two weeks in the spring of 1935 he got through Proust, Mann, a chunk of Paradise Lost, fifteen chapters of Boswell’s Life of Johnson, some Maupassant, Lessing, and poems by Donne, Wilfred Owen, and Housman. He was also making his way through the classics of Marxism and honing his skills as a debater. Passionate in his Marxism (he wanted to love it “like one loves a woman”), he endured a couple of dull local Labour Party meetings and came to appreciate the strangely ambivalent relationship of the British left to anything that smacked of Continental socialism.

At Cambridge, where his erudition and omniscience caused him to stand out, he got his first taste of the British elite in all its contradictions—its intellectual self-assurance and its parochialism, its sociability and its snobbishness, and its openness to an outsider like him. His love of university life emerges from a piece he wrote on the eve of the war for his old school magazine:

In the afternoons I can sometimes see Colmer paddling up to Grantchester in a canoe, looking fit. I expect, if I really tried, I could see Pulvermacher too, but it is difficult to recognise everybody in the seething mass of canoes and punts, particularly when handling a punt-pole. Your correspondent is generally handling one and getting his trousers soaked in the process…. Just now Colmer is reading a Penguin Book, and Hobsbaum [sic] has a hangover from one of the larger end-of-term parties…. Cambridge is, after all, a pretty good place to be at, even in 1939.

His career there was stellar: he became editor of The Granta, as it was called at the time, and then, at the age of twenty-two, was elected a member of the Apostles, the legendarily exclusive club that included John Maynard Keynes, E.M. Forster, the spy Guy Burgess, and Leonard Woolf among its members. Much as in a college tutorial, the Apostles’ meetings assumed a kind of intellectual equality between older and younger, don and student, jousting on the battlefield of ideas. Lacking any doubt in his own abilities, Hobsbawm excelled. His intonation—a barked midcentury English, somewhere between senior common room and army barracks—reflected this self-confidence. So did his approach, retained for the rest of his life, to intellectual inquiry. What subsequent generations might have regarded as rudeness or aggression was to him simply about getting down to the thing that really mattered—the collective pursuit of the truth. Perhaps because this intellectual style was essentially impersonal, it seemed all the more liberating to him.

We first hear his trenchant tone in a scholarly setting in 1950 in Paris, at the ninth international congress of historical sciences. This was the first great gathering of historians to take place after the war, and virtually all the luminaries of the profession were there; he had probably been invited thanks to his mentor, the Cambridge don Michael Postan. Next to men like the renowned French economic historian Ernest Labrousse, Hobsbawm was a relative nobody. In the section on economic history, Colin Clark, a pioneer in the usage of national income estimates, provided a paper on contemporary trends in the field. Clark’s approach tended to wave away conflict and struggle in its portrayal of the triumphal march of economic progress. Hobsbawm got up to comment. “The paper by Clark,” he began, “is an example of what not to do in economic history.” No one could ever accuse him of not being clear.

Because we think of Hobsbawm primarily as a scholar, it is easy to overlook how important writing itself was for him when he was young and how badly he wanted to write. For many years, stories, mood pieces, sketches, and diary entries poured out of him. At Cambridge he wrote for The Granta, and later he contributed to the popular illustrated monthly Lilliput. During the war he proposed a series of accounts of barracks life to the army that had turned him down, already suspicious of his political views. One of the reasons he embarked on graduate work—a rather unusual choice in 1946—was that he believed history would give him “plenty of scope for writing.” Even while working on his doctorate, he reviewed regularly for the TLS and began broadcasting on an immense range of subjects for BBC Radio.

Advertisement

Thanks to his own brilliance and to Postan’s patronage, Hobsbawm was elected to a research fellowship in Cambridge, and in 1947 he obtained a permanent job as lecturer in economic and social history at Birkbeck. In the summer of 1950 he successfully defended his dissertation on the Fabians, a subject he would not return to. Having started off publishing on Bernard Shaw’s socialism, his scholarly research took him deep into the nineteenth century and then earlier still. Birkbeck was a good place for a labor historian. It was no ivory tower; its undergraduates were working people who could attend classes in the evenings. It became his home for the rest of the century, a training ground for the kind of approachable scholarship he became known for.

His work was approachable not only because of the clarity of his thought and expression but also because of his understanding of history, and of how the discipline was changing. In an essay he published in the TLS in October 1961, he wrote:

Throughout the past twenty-five years the established if unofficial orthodoxies of academic conservatism have been increasingly on the defensive. These orthodoxies, broadly speaking, confined the field of general history…to the chronological narrative, supplemented here and there with ad hoc explanations, of the upper ranges of politics, diplomacy, war…. They also saw the primary task of research in the discovery, on the basis of carefully evaluated documents, of “what actually happened.”

This traditional focus had been altered, he went on, by a twofold change. Haltingly but unmistakably, people had come to recognize—prompted not only by Europe’s self-immolation in war but by the fate of the postwar European empires and the anticolonial struggles in the Third World—that history needed to encompass the globe. At the same time, the primacy of political, diplomatic, institutional, and military history had been threatened by the rise of postwar social science and a concomitant turn toward social and economic history. He was among those who welcomed these changes.

The history profession in Britain had been slow to adapt, and the drivers of intellectual change were mostly to be found outside college lounges, in the leftist culture of workers’ education and outreach that was spreading through the Labour Party and the Workers’ Educational Association. The Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB), which Hobsbawm had joined, was also involved. The party was, as he understood very well, a political failure—arguably the least successful Communist party in any major European country—but one enduring achievement was its Historians Group. This emerged—despite, rather than thanks to, the party’s leadership—around Hobsbawm and a few other comrades who shared an interest in the history of labor and working people. In 1950 the group decided to found a new journal, which appeared for the first time two years later under the title Past and Present and which became the flagship of a new, more inclusive, more outward-looking approach to historical studies.

At the outset, the editors of Past and Present identified social transformation as their core concern, and made it clear that their remit extended across time and space. Noting the continued validity of the “scientific technique which nineteenth century historical scholarship built up,” they inveighed against both idealism and the false god of objectivity. Above all, they promised to “make a consistent attempt to widen the somewhat narrow horizon of traditional historical studies among the English-speaking public.” There was nothing especially Communist about any of this, and they soon enlarged the editorial board of the journal by bringing in several new members who had no party affiliation.*

That first issue of Past and Present explicitly identified the French Annales school of Marc Bloch and Lucien Febvre as a source of inspiration. Paris was where this shift to social and economic history had really begun, and Hobsbawm was in the process of developing close ties with French historians. He had fallen in love with the French capital while visiting it during the Popular Front years, but after the war it came to offer him intellectual as well as emotional sustenance and inspiration. At the congress in 1950 he came into contact with what he later described as a “curious collection of (then) historically marginal characters”: Jean Meuvret, Pierre Vilar, Ernest Labrousse, and the Polish Holocaust survivor Marian Malowist—remarkable historians who would become intellectual partners and, in many cases, friends. Generally they were on the left, but few were members of the French Communist Party, and some—such as Meuvret and Fernand Braudel—were not on the left at all: Hobsbawm was always heterodox in scholarly matters. What they shared was the formative experience of depression, fascism, and the war, and a commitment to history as the indispensable tool for understanding the present.

The argument that history would be enriched by the social sciences, indeed that history was a social science itself, perhaps even the queen of them all, drove Braudel to build a new powerhouse at the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales and later the Maison des Sciences de l’Homme. Fluent in French, Hobsbawm worked closely with these institutions, making frequent trips to them. He was especially close to Braudel’s right-hand man Clemens Heller, and in the 1970s the two men organized seminars on European social history that brought together an extraordinary array of leading figures from both sides of the Atlantic, including Pierre Bourdieu, Charles and Louise Tilly, Edward and Dorothy Thompson, Natalie Zemon Davis, Joan Scott, and Michelle Perrot. One might say that the energy others threw into political activism, Hobsbawm devoted to his profession: these seminars were typical of his unsung but crucial work behind the scenes. His unglamorous perch at Birkbeck, on the margins of academia, was perhaps an advantage. Had he been at Cambridge or Oxford, his attention would have more likely been diverted into inconsequential matters of college life: his near contemporary Hugh Trevor-Roper, for instance, a stylish writer and a don who garnered many honors, had much less of an impact on the field. It was Hobsbawm who in his writings and his work did more than anyone to shape the discipline of history over two or three decades.

It probably helped that Hobsbawm’s maturity coincided with a golden age of mass reading, as rising school and higher education participation rates after World War II fed the popular appetite for accessible learning. The buying of books in midcentury Britain was extensive—far greater on a per capita basis than it was, for instance, in the United States—and it had accelerated thanks to the paperback revolution that had taken place in the 1930s with the founding of Penguin Books.

Allen Lane’s pioneering Pelican imprint testified to the popularity of nonfiction in particular. It was followed after the war by other specialist “egghead imprints” (as historian Peter Mandler has dubbed them), like Mentor in the US. R.H. Tawney’s Religion and the Rise of Capitalism, in print with Pelican since the 1930s and Mentor since 1947, was one of the top sellers in the postwar era. In the 1960s Fontana—a paperback imprint of Collins that had published Agatha Christie, spiritual tracts, and wartime memoirs in the 1950s—initiated an influential History of Europe series. Pelican published Carlo Cipolla’s Economic History of World Population in 1962, the same year that Hobsbawm’s Age of Revolutions was published by Mentor in the US. It is no coincidence, as Marxists like to say, that the apogee of serious nonfiction publishing in paperback was exactly when Hobsbawm became a household name. His timing was fortunate.

His mastery of his craft also had much to do with his success. Although Hobsbawm’s works would be used in college courses for generations, they were not textbooks, and indeed he was skeptical about the genre where history was concerned. In his view, history, unlike the natural sciences, lacked a “body of accepted questions and potential answers,” so that what filled the gap tended to be boring narratives of an old-fashioned kind that were not so much wrong as “irrelevant.” He characterized his own work as “haute vulgarisation…for the intelligent and educated citizen”—high-level, argument-driven syntheses. Written in invigorating prose, his books gave readers a sense of the sweep of historical change. As he noted, describing a web was harder than telling a story.

His achievement was to show how seemingly disparate phenomena such as the emergence of new words, ideas, and art forms, trends in urbanization, and the rise and fall of dynasties were interconnected and in fact could only be understood in relationship to one another. This sort of thing is much harder to do than it seems: part of Hobsbawm’s skill as a writer was to conceal the depth of his research and the sophistication of his analysis. It was sometimes said that he was not an archival scholar, but this is not true, as shown by books such as Captain Swing, which brought rural English society to life through written documents in a study of the antimachine agricultural riots of the 1830s. Yet as history, like other disciplines, became ever more specialized, the skill in shortest supply was that of synthesis. Of this he was a master.

By the late 1980s, Hobsbawm had achieved worldwide fame. He was unquestionably the best-known historian of the left, gaining attention more broadly through his 1978 Marx Memorial Lecture, “The Forward March of Labour Halted?” Published in a relatively obscure journal called Marxism Today, it was an unsparing analysis of the challenge ahead for socialists as the postwar social consensus unraveled and Thatcher’s new brand of conservatism profited. “The Forward March” identified the forces fragmenting an older working-class unity: women and immigrants entering the labor force in increasing numbers, nationalism and racism making inroads within traditionally working-class areas across the United Kingdom. The rise of a postwar radical constituency made up of students and white-collar workers who had little in common with the old labor socialism further intensified the heterogeneity of the left. Tragically, in Hobsbawm’s view, these factors threatened to weaken what he called ”the working class and its movement” at the very time when capitalism was entering a period of acute world crisis. Forty years on, the critique remains convincing, and not only for Britain.

Hobsbawm had been an activist as far as back as the winter of 1931–1932, when he distributed anti-Nazi pamphlets for a group associated with the German Communist Party. His affiliation with the CPGB, an open secret, kept him under surveillance during and after the war. Yet as both party bosses and the watchers in MI5 had known for a long time, obeying the party’s line took second place to his intellectual concerns. Ideologically, the CPGB favored folk music over jazz, to take one example, but this did not stop Hobsbawm from writing on jazz (under the pseudonym Francis Newton) in the New Statesman for years.

While he remained in the party after the invasion of Hungary in 1956, he made his disagreements known internally. At various times, party leaders hoped he would resign: perhaps that too was a reason he did not. One thing is clear: membership in the party was not, for Hobsbawm, about working in any active sense toward revolution. He was, by circumstance and inclination, an observer, sharing Dos Passos’s view that “I was a writer, writers are people who stayed on the sidelines as long as they could.” His form of activism was writing and teaching.

Once the Berlin Wall fell, Hobsbawm’s communism received a good deal of attention, especially after the 1994 publication of The Age of Extremes: The Short Twentieth Century, the book that completed the tetralogy he had begun with Age of Revolutions some thirty years earlier. Although the four volumes had not been conceived as part of a single work, they were driven by a grand ambition: to follow the rise and transformation of industrial capitalism and the social changes this generated, first mostly in Europe and increasingly around the globe. Yet it was not so much Hobsbawm’s approach as the more personal question of his own relationship to the Communist Party of Great Britain that the media, especially in Britain, now focused upon.

Asked repeatedly by journalists and interviewers why he had remained a member of the party, Hobsbawm usually said he had not wanted to let down former comrades, but this did not seem very convincing, especially given his close friendships with figures across the political spectrum. Perhaps the real explanation lay elsewhere—in the fact that the party had given him a home just when he lost his parents and Europe was being taken over by fascism, though this was not the kind of answer a man like Hobsbawm, disinclined to psychologizing, would have offered.

Party membership had affected his work in at least one way. In conversation with the Italian journalist Antonio Polito, a long-time member of the Italian Communist Party (and possibly the only man to have been expelled from the party for playing tennis), Hobsbawm admitted that his desire to avoid saying things that might have wounded the feelings of his comrades had led him to focus on the nineteenth century rather than the twentieth. As this suggests, his communism had driven him back into areas of history where he could be sure it would be largely irrelevant. (Many outstanding postwar Polish and Romanian historians specialized in medieval history for similar reasons.) Intellectual freedom while writing about his chosen subjects had been the paramount consideration. Unavoidably, Age of Extremes—his only major treatment of twentieth-century European history—had forced him into uncomfortable territory and was a lesser book for it.

Unlike his communism, his Marxism had enriched his work and was inseparable from it. Since his days at Marylebone Grammar, Hobsbawm had valued the way Marxism regarded history as a set of evolutionary changes punctuated by crisis. The emphasis on crisis was crucial, and if his evolutionism waned with time, the fundamental view of capitalism as a system of catalytic crises based on fundamental inequality did not: it was one of the things that ensured his work continued to speak to readers into a new century, long after the demise of the USSR.

Marxism also underpinned his view that the past had to be seen and understood as a kind of totality. History was, in Hobsbawm’s understanding, indivisible, and to be a social historian—the title he had adopted since the 1950s—meant trying to convey change in the round. “To divide social history from the rest of history is only a device of technical specialisation,” he had noted in Paris in 1950. “Though for practical reasons, we are specialised ‘social historians,’ our aim is not to write ‘social history’ but History which cannot be subdivided in real life.” Unlike some Marxist historians who focus on material concerns, Hobsbawm had a conception of economic history that was never purely economic. He was always too curious about music, Hollywood, and fiction—about matters of culture high and low—to want to relegate such things to a secondary role.

Asked about Marx’s relevance in the early twenty-first century, Hobsbawm underscored the “universal comprehensiveness of his thought.” Some critics object that such a definition has scarcely anything to do with Marx at all, but in fact this holistic approach to understanding social change, along with the focus on crisis and the underlying concern with social equity that Marx also provided, could not be easily attained in other ways. One only has to look around at the increasing specialization of academia today, more advanced even than in Hobsbawm’s day, to see how rare it is.

A Marxist then, but an undogmatic and easily accessible one, Hobsbawm belonged to a generation that emphasized the intellectual’s responsibility to help create an intelligent citizenry. Theoretical virtuosity or purity was beside the point; plain English was never superfluous, for scholarly research was of little value if it could not be understood by society at large. It was in this sense, perhaps, that Hobsbawm’s politics provided both a kind of ethics of scholarly practice and a vision of a collective readership. Not a storyteller himself, Hobsbawm welcomed the return of narrative history in the 1980s. Yet most of today’s historians who pride themselves on being able to spin a good yarn care little for making arguments: the anecdotes are good, but the analysis is often thin. Hobsbawm’s legacy lies in the model his writings provide for bringing argument alive, in the reminder they offer that history is a communal enterprise, open-ended and open-minded. We will be reading his books for a long time to come.

An earlier version of this essay misidentified Fernand Braudel’s “right-hand man” as Jacques Heller, not Clemens Heller.

This Issue

July 23, 2020

Unpresidented

Sun Ra: ‘I’m Everything and Nothing’

-

*

Past and Present, Vol. 1, No. 1 (1952), pp. i–iv. ↩