1.

The rediscovery of long-forgotten women who were major participants in the creation of modern architecture—a restitution effort that arose with second-wave feminism in the 1970s—has had significant consequences. Not least of them has been an ongoing revision of the architectural canon, with unjustly overlooked female pioneers added to the once exclusively male pantheon of modernist master builders. Arguably the most fascinating and elusive of these path-breaking women is the Anglo-Irish architect and furniture designer Eileen Gray, who has come into much sharper focus during the past decade thanks in large part to a network of outstanding female scholars in the United States and Europe.

Interest in Gray was spurred by an excellent retrospective in 2013 at the Pompidou Center in Paris that then traveled to the Irish Museum of Modern Art in Dublin, and several of those involved in it regrouped for “Eileen Gray,” an even better survey that opened at the Bard Graduate Center Gallery earlier this year. Although the Covid-19 pandemic forced the premature closing of the New York show—a ravishing installation of two hundred objects, many of them great rarities—it will be long remembered because of its catalog, admirably edited by Cloé Pitiot and Nina Stritzler-Levine in a tour-de-force of exhaustive research and insightful interpretation. It was imaginatively designed by the Dutch graphic artist Irma Boom to evoke Gray’s aesthetic, right down to the three-tone grisaille fore-edges in homage to her geometric rug patterns, and is now the indispensable reference work on the subject.

Nevertheless, Gray remains an enigma. In contrast to such dynamos of the 1920s as Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky and Charlotte Perriand, the temperamentally reticent Gray seems to have abetted her lingering obscurity. This was her besetting psychological struggle, which she was apparently aware of, according to her attentive friend and authorized (if sometimes unreliable) biographer, Peter Adam, a German-born British documentary filmmaker who died last year shortly before the publication of Eileen Gray: Her Life and Work, a revision of his Eileen Gray: Architect/Designer (1987).

For decades Adam monopolized information about Gray through his closeness with her niece, heir, and gatekeeper, the British artist Prunella Clough, and this likely did her reputation more harm than good. Gray’s standing as an architect was further undermined by her being primarily identified as a designer of furniture and interiors. She moved incrementally in scale from small individual objects to larger ensembles, then entire interiors, and finally buildings, a progression all the more astounding because she was self-taught in architecture, save for private instruction in technical draftsmanship from the Polish architect Adrienne Górska (sister of the Art Deco artist Tamara de Lempicka) in order to design her initial house.

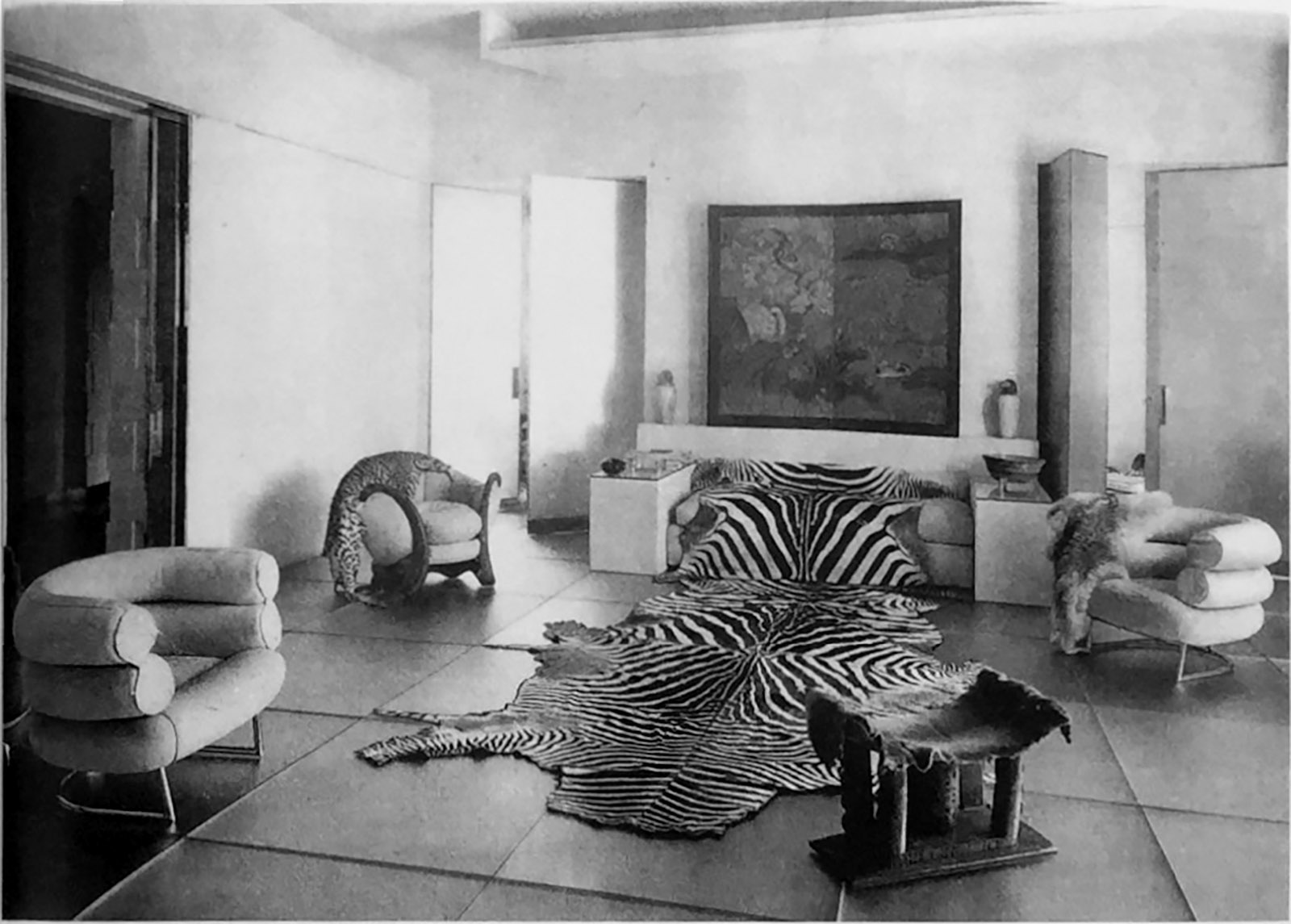

Gray’s first complete interior design commission was a Paris apartment for the couturière Suzanne Talbot (1919–1924; see illustration below). Among the pieces she made for this innovative residence was her Brick screen, an ingenious composition of thin lacquered wood oblongs stacked on invisible vertical rods and horizontally staggered in alternating, pivoting rows to create solid/void rhythms akin to a three-dimensional Escher checkerboard. Another brilliant reinvention was the Lota sofa (1924), a notable departure from the upright upholstered seating of the period. Deep, low-slung, and capacious, at once daybed and divan, it is flanked by built-in rectangular lacquered monoliths big enough to serve as end tables. In addition to a pair of loose back pillows, this nearly eight-foot-wide mega-couch has two large square cushions that can be moved around to individualize it for different body types. This is the most inviting and comfortable domestic furniture I’ve ever experienced, as I did for years in the London guest flat of friends who owned a later “re-edition” of this divine divan.

Gray’s labor-intensive lacquer was affordable to only a few rich sybarites, and that remains true a century later. In 2009 her Dragon armchair (1917–1919)—an overstuffed fauteuil embraced by two sinuous curves of carved lacquer—fetched more than $28 million, the world record auction price for twentieth-century furniture. Yet her later modernist designs in metal and other workaday materials were hardly inexpensive, for despite their machine-made appearance they, too, initially had to be handcrafted. Her flair for adaptive multifunctionalism is displayed in these later designs, such as tables that expand in height and length to accommodate different tasks; the Satellite mirror (1926–1929), which combines a large circular looking glass, a smaller magnifying mirror on a pivoting arm, and a round built-in light; and a streamlined painted-wood contrivance (1930–1933) that could be used as a stepstool, a seat, or a towel rack. Her best-selling items were hand-loomed wool rugs in abstract geometric patterns that reflected concurrent Russian Constructivist and Dutch De Stijl concepts but were woven using techniques that she learned from Berber women, famed for their durable carpets, during a trip to North Africa in 1908–1909.

Advertisement

2.

In contrast to her prolific interior design output, Gray’s executed architecture was limited to three houses, all built for herself. The finest of them, an International Style villa at Roquebrune-Cap-Martin on the Côte d’Azur between Monaco and the Italian border (see illustration on page 47), is now so esteemed that her proponents insist that if Gerrit Rietveld, Giuseppe Terragni, and several other highly regarded male modernists are included in survey histories on the strength of a single surpassing work, Eileen Gray ought to be too.

The building was erected between 1926 and 1929 on a breathtaking seafront site steps away from the Mediterranean, perched atop ancient stone-walled terraced vineyards below the Riviera corniche and the coastal railway line. Known in early publications as Maison en bord de mer (house on the edge of the sea), it was named E.1027 by its makers in a cryptic numero-anagram intended to be as revolutionary as the scheme itself. It combines Gray’s initials—“E” for Eileen, and “G” signified by 7 for the alphabet’s seventh letter, with 10 and 2 for the alphabetic order of J and B, for Jean Badovici.

At some unknown point in the early 1920s, Gray, then in her mid-forties, had begun a deep involvement with Badovici, a charismatic if caddish Romanian architect fifteen years her junior. He admired her artistry, encouraged her architectural ambitions as no one else had, and wrote enthusiastically about her work for the first of many times in 1924 in his influential avant-garde design journal, L’Architecture Vivante. Such rapturous praise could have turned anyone’s head:

In it there is an atmosphere of endless malleability, where different spatial planes meld, where individual objects are fully grasped only when they are perceived together in a transcendent mysterious and animated scheme. For Eileen Gray, architectural space is a material to sculpt, a material that can be transformed and shaped according to the needs of the decor. Space provides Gray, the artist, with infinite possibilities to create.

She achieved that magnificently with E.1027. Its simple, flat-roofed, white-walled, rectangular format was based on Le Corbusier’s Villa le Lac of 1923–1924 in Corseaux, Switzerland, a small, single-story structure he built for his parents on the shore of Lake Geneva. Badovici had told Gray of his desire to have a quiet little retreat in the south of France and suggested that she design it (and pay for it, which she did in anticipation of their sharing a happy life there. However, Badovici bought the land, despite the Bard catalog’s claim that Gray financed that as well). Although she initially demurred because of her lack of architectural experience, he promised to lead her through the design process, and his good friend Le Corbusier offered the detailed plans for Villa le Lac to serve as an easy template for another waterfront setting, albeit quite different from Lake Geneva.

Gray, a quick study with heretofore unfathomed depths of architectural talent, used Le Corbusier’s scheme as a jumping-off point but came up with a solution far more subtle and nuanced than his rather inert, earthbound lake house. She lifted E.1027 up one story on Corbusian piloti columns to take further advantage of the panoramic Mediterranean vista, and in contrast to the Swiss model devised layers of peripheral screening, retractable windows, and shading strategies that break down barriers between indoors and outdoors to mesmerizing sensual effect. Her handling of the cool but seductively arranged interiors, furnished with her own designs, blurred the usual boundaries between architecture, built-ins, and freestanding objects. Gray rejected Le Corbusier’s oft-quoted definition of the modern house—une machine à habiter (a machine for dwelling in, not, as it is usually mistranslated, a machine for living)—and with her attentiveness to the psychological aspects of space proposed an alternative: the house as “the shell of man, his extension, his release, his spiritual emanation.”

Le Corbusier was astonished and furious that a woman could beat him so decisively at his own game, and E.1027 became a lifelong obsession for him because, as he later complained to an architectural apprentice, Gray “stole” his design. After she and Badovici split because of his compulsive womanizing, she gave him sole ownership of E.1027 and moved to Tempe a Pailla (1933–1936), another superbly considered but more rustic house that she designed and built in Castellar, northeast of Roquebrune. (The last of Gray’s houses for herself was Lou Pérou of 1954–1963 in Saint-Tropez, a vernacular conversion of a disused stone vineyard shelter.)

In 1938, Le Corbusier, who sought acclaim not just as an architect but as a fine artist, convinced Badovici that E.1027 would be enormously improved by the addition of murals and offered to paint them himself. Without either of them asking Gray’s opinion, Le Corbusier imposed eight garish Picassoid daubs on the walls of her masterpiece. He thereby wrecked the serenity of its interiors and subverted her architectural vision in a jealous fit of artistic aggression. That there was a subconscious sexual component to Le Corbusier’s act is suggested by his having painted the murals in the nude, as photographs attest. Adding insult to injury, after World War II the house was standardly credited not to Gray but to Badovici or Le Corbusier himself, misattributions the men never bothered to correct. During and after World War II the structure endured countless depredations, but a decades-long restoration campaign has at last been completed and, accurately decorated with Gray’s furnishings, it is now open to the public as a French national historical monument.

Advertisement

E.1027 is the subject of a monograph edited by the architect Wilfried Wang and Peter Adam, with entries by several other contributors. Although it is agreed to be among the greatest houses of the twentieth century, there is less unanimity about its exact authorship, which has often been jointly assigned to Gray and Badovici. Yet in Marco Orsini’s informative documentary Gray Matters (2014), her soundest biographer, Jennifer Goff, states unequivocally that “E.1027 is Eileen’s complete, independent project from start to finish.” And the eminent architectural historian Joseph Rykwert, whose 1968 appreciation of Gray in the Italian design journal Domus launched her critical resurrection, calls it “a very odd collaboration, because [Badovici] actually wasn’t a very good architect. I’ve seen designs of his, and they were pretty crummy.”

Gray Matters was co-produced by the Irish film director Mary McGuckian, whose historical drama The Price of Desire (2015) depicts a Gray-and-Badovici romance (as well as her relationship with the torch singer Damia, played by Alanis Morissette). It is pretty but stilted, with such leaden dialogue as Gray saying, “I gather there’s been some dispute as to whether or not I invented the first piece of tubular steel furniture.”

3.

Kathleen Eileen Moray Smith, the last of her parents’ five children, was born into high privilege in 1878 at Brownswood, a hundred-and-fifty-acre estate in Enniscorthy, County Wexford, Ireland (not far from Dunganstown, the ancestral village of America’s Kennedy dynasty). The marriage of her father, James Maclaren Smith, a mediocre middle-class Scottish painter, and her mother, Eveleen Pounden, a Scots-Irish aristocrat whose father left her the present-day equivalent of $70 million, was a classic Victorian mésalliance. Although Eileen cherished memories of an idyllic Irish childhood, when she was eleven her father left permanently for Italy and the Smiths later divorced, a much greater disgrace in those days than it is now.

From her father she inherited more artistic talent than he ever evidenced; from her mother she received the money that allowed her to pursue career goals then rarely open to women of any class. Yet that lifelong financial security cushioned Gray from having to earn a living through her art, which might have been to her professional disadvantage. In 1895 her mother became the nineteenth Baroness Gray after the death of an uncle whose ancient Scottish peerage could pass to female descendants, unlike the English men-only practice. Thereupon the Smiths assumed a new surname, and the youngest daughter was restyled the Honorable Kathleen Eileen Gray, though she never used her first name or courtesy title. The new Baroness Gray’s social elevation prompted a thoroughgoing remodeling of Brownswood House from a gracious but unpretentious Georgian country seat to a pompous Elizabethan Revival pastiche, which the aesthetically sensitive Eileen lamented for the rest of her life.

The family divided its time between Brownswood and its London mansion at No. 14 The Boltons, a fashionable garden square near the South Kensington Museum (later renamed the Victoria and Albert). The museum’s peerless collection of decorative art was a lodestar for Gray, especially its exquisite examples of Chinese and Japanese lacquer. The material so enthralled her that she persuaded the proprietor of a Soho furniture repair shop to teach her the rudiments of lacquer making, and she later undertook an arduous apprenticeship with the expatriate Japanese lacquer master Seizo Sugawara, which extended into a fruitful twenty-year collaboration.

In 1898 she was presented as a debutante at Buckingham Palace, a coveted royal ritual that marked an upper-class girl’s formal entry into London society and the marriage market. Gray, described by one female friend as “fair, with wide-set, pale blue eyes, tall and of grand proportion, well-born and quaintly and beautifully dressed…the most romantic figure I had ever seen,” had many suitors, and one male admirer described her shoulders as “the most perfect I ever saw.”

Yet she was also shy, stubbornly independent, skeptical of accepted opinion, and rather than feeling any urgency to find a suitable husband was more avid to learn the techniques of art. London’s Slade School of Fine Art, the best in Britain at the time, was deemed a suitable finishing academy for young ladies of her caste, and she enrolled there in 1900. After two years Gray moved to Paris to continue her art studies. She liked the city so much that in 1907 she bought an apartment in an eighteenth-century Left Bank hôtel particulier on the rue Bonaparte that remained her home until her death seven decades later.

She soon fell in with two distinct coteries of young avant-gardists: the Irish expatriate community of experimental-minded artists and writers who found the French capital a more congenial creative climate than that of their conservative homeland (Joyce arrived in 1920), and a multinational circle of lesbians who gravitated to Paris because of its sophisticated tolerance, the most famous couple among them being the San Francisco Bay Area natives Gertrude Stein and Alice B. Toklas. Gray’s romantic life has been the source of considerable speculation, but even though she always conducted herself with an aristocrat’s disregard for the opinions of others, she was extremely discreet, and thus little is known about her erotic affairs.

In those youthful days she enjoyed going out with a female friend who dressed in male drag with a fake moustache and promised, “I can take you to places where you can’t go without a man.” But Gray was also courted by numerous men, including the English occultist and writer Aleister Crowley, who dedicated his 1904 poem “Eileen” (“the eyes/Of melancholy wind; The voice serene/Of the love-moved wind”) to her.

One of Gray’s most serious same-sex relationships was with a theatrical manager known professionally as Gab Sorère, the lover of Loïe Fuller, the American-born modern dancer whose celebrated Serpentine Dance—a choreographic tornado of billowing silk—inspired fin-de-siècle artists as varied as Toulouse-Lautrec, Rodin, and the Lumière brothers. According to Cloé Pitiot in the Bard catalog, Sorère, who dressed like a man, was enlisted by Gray to run Galerie Jean Désert, the Right Bank retail shop that she opened in 1922 to sell her furniture and rugs but closed in 1930 during the Great Depression. However, the architectural historian Tim Benton has disputed Sorère’s involvement in the business based on his archival research, another example of dissent among even the most knowledgeable Gray experts.

After Fuller’s death in 1928, Sorère took up with Gray’s female romantic partner of several years, the chanteuse réaliste Marie-Louise Damien, called Damia, whose doleful persona was copied by the younger, better-remembered Édith Piaf. (Damia’s pet name for Gray was Panachot, after the male title character in Panachot Gendarme, a popular military vaudeville.) Who knows what this bisexual version of La Ronde actually entailed and in what sequence Gray’s possible coupling, uncoupling, and recoupling with Sorère, Damia, and Badovici occurred? As Pitiot writes about part of that complex equation:

We leave it up to other writers to determine if Gray and Badovici were lovers. The conjoining of their names [in E.1027] suggests a close connection, but the level of intimacy is unknown and its actual direct relevance to the architecture questionable.

4.

A perceptive and wholly plausible reading of the protagonist’s conflicting emotions is to be found in an extraordinary graphic novel, Eileen Gray: A House Under the Sun, written with sensitivity and tact by the French architect Charlotte Malterre-Barthes and illustrated with complementary wistfulness by the Polish graphic artist Zosia Dzierżawska. It rings true not only in its factual aspects, but especially in its poignant acknowledgment of Gray’s essentially divided nature. The book skillfully intercuts flashbacks that juxtapose aspects of Gray’s inner life in illuminating ways. For example, her neglectful Irish upbringing is depicted not as the prelapsarian paradise the architect recalled, but more like one of the Gothic ordeals in Edward Gorey’s Gashlycrumb Tinies. Her immersion in the giddy lesbian demimonde of 1920s Paris is no less vividly portrayed, as in a depiction of a freewheeling soirée at the American novelist and saloniste Natalie Barney’s Temple d’Amitié, her Neoclassical garden folly on the Left Bank, a short walk from Gray’s flat.

In Conversation with Eileen Gray—a short documentary film by the French director Michael Pitiot, Cloé Pitiot’s husband—gives us a tantalizing first-person sense of this shadowy creature as well as a delightful sampling of her hesitant, plummy, patrician voice, truly of another age. Based on a previously unreleased 1973 audio interview with Gray by the British architect Andrew Hodgkinson, its hushed reverence brings to mind a David Attenborough program about some furtive endangered species. Their dialogue was recorded while she leafed through a portfolio of her designs and commented briefly on each, to which Pitiot has added images of the works they discuss. Gray was never given to theoretical statements, so the gold nugget here is her explanation of the dramatic stylistic shift she made around 1920 from traditional figurative motifs to the abstract modernist forms that typified her oeuvre from then on:

I think one changes. You see, at that time I really didn’t appreciate modern art. Now, of course, one would want to do anything in decoration perfectly different…. I’ve always liked abstract things…. I don’t like things so delimitated, you know? I think that when you see figures, well there it is, you see it, and you take it in, or you absorb it, and then it’s done, really. Whereas an abstract, sometimes it can look so entirely different, don’t you think?

Paradoxically, Gray was too proud to pursue the critical recognition she deserved, but resented that her lesser male contemporaries were lionized while she languished in oblivion. Going through Gray’s papers, Peter Adam found her handwritten transcriptions from the American self-help writer Dorothea Brande’s 1936 best seller Wake Up and Live! (which is still in print). These improving tips urged “the removal of shyness,” instructing the reader to “act as if it was impossible to fail” and to “recollect past failures and set free whatever group of aptitudes is for the moment required.” But by her own admission Gray was achingly lonely and grew more agoraphobic as she got older.

She was constitutionally unable to fully savor her astonishing comeback when it came at last, part of a comprehensive reappreciation of the Art Deco style in the late 1960s and 1970s. Soon a steady stream of perspicacious design curators, eager dealers, canny collectors, and starstruck culturati (including Bruce Chatwin, who became a friend) arrived at her door on the rue Bonaparte in hopes of seeing and in many cases acquiring objects known only through dim period illustrations and almost impossible to find in the antiques trade.

High-style furniture entrepreneurs such as Andrée Putman in Paris and Zeev Aram in London shrewdly discerned that well-made replicas of Gray’s designs would appeal to aficionados bored with overly familiar modernist classics by Le Corbusier, Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, and Marcel Breuer. Both Aram and Putman bought rights to reproduce a number of her chairs, tables, mirrors, lighting fixtures, and rugs, and their “re-editions” (which sounded less fake than “reproductions”) became a commercial success.

All the while Gray continued to produce strong new designs, such as a four-panel notched screen of natural cork (1960–1973) so elegantly formed and proportioned that this humble, lightweight material looks as noble as burnished travertine. As she once told Badovici, “The choice of a material that is beautiful in its own right, worked with a sincere simplicity, is sometimes sufficient.” Yet her new plutocratic fans preferred her luxurious early output, and with few takers she wound up offloading the cork screens at cost.

She kept working right up until her death at age ninety-eight. Her final completed design was a hinged screen with three alternating concave/convex curved panels of shocking-pink celluloid, an uncharacteristic color choice but typical of her striking out in unexpected directions. In the fall of 1976 she asked her devoted housekeeper of half a century to buy wood for a new tabletop she was eager to make, but suddenly slipped into unconsciousness and died six days later. Eileen Gray’s most famous aphorism—“To create, one must first question everything”—speaks to this consummate contrarian’s restless and unrequited quests in life and art.

This Issue

September 24, 2020

Ball Don’t Lie

A Second Chance

Making Order of the Breakdown