For now, democracy is hanging on. I’ve been writing presidential election postmortems every four years since 1992, and I never imagined I’d open one with that sentence. But despite Joe Biden’s impressive and necessary win, this is the lesson of the 2020 election: our democracy remains intact, at least for today. We learned emphatically this year that the political chasm that opened in this country in the 1990s is wide and deep and—for the foreseeable future, and in spite of the president-elect’s rhetoric—likely to grow wider and deeper, threatening the idea that we can long continue as one nation. This was not a given going into the election. In the weeks before November 3, when we believed those sunny polls, Democrats anxiously whispered the word “landslide.” I was hearing projections from people—knowledgeable people with experience on presidential campaigns—that Biden might top 350 even 400 electoral votes, which surely would have meant, in turn, as many as fifty-three or fifty-four Democrats in the next Senate, and ten or fifteen new Democrats in the next House.

Such a result—with Florida, North Carolina, Ohio, maybe even Texas turning blue—would have forced a reckoning upon the leaders of the Republican Party, giving rise to a restive faction within it (led perhaps by Mitt Romney) that would compromise and modernize, by agreeing to strike actual legislative deals with Democrats, say, or by reducing the blatant racial and ethnic bigotry the party so regularly peddles. Instead, the results of the congressional elections were very strong for Republicans, strong enough to affirm to them that their basic direction is fine. They just need to find a standard-bearer who is less obviously a gangster and an incompetent.

The election demonstrated, more intensely than any other before, that Americans inhabit two different moral universes. In our personal lives, we may share broadly similar ideas about what constitutes right and wrong: how to raise children, how to be responsible friends and family members. But on political matters, we see two opposite realities. This is largely the work of Fox News, Rush Limbaugh, and the rest of the right-wing media—now including admirers and imitators like Newsmax and the One America News Network—plus the ecosystem of right-wing Facebook chat rooms where lies begin, spread, multiply, and eventually get retweeted by the president. (One rumor, started by QAnon, the lunatic conspiracy theory, had it that John F. Kennedy Jr. did not die in a plane crash in 1999 and was slated, on October 17, to emerge from hiding, join Trump at a rally in Dallas, the city where his father was assassinated, and accept Trump’s offer to become his running mate.) Disinformation campaigns circulated: for instance, The New York Times reported that videos of Biden edited to show him “admitting to voter fraud” were viewed more than 17 million times before election day.

This creation of an alternate reality has been most chillingly evident in the Republican discussion of the Covid-19 pandemic. During the party convention in August, White House economic adviser Lawrence Kudlow spoke of the virus in the past tense. “It was awful,” he said:

Health and economic impacts were tragic. Hardship and heartbreak were everywhere. But presidential leadership came swiftly and effectively with an extraordinary rescue for health and safety to successfully fight the Covid virus.

The twisting of official reports to defend Trump’s response—claims, based on a willful misreading of a report by the Centers for Disease Control, that Covid has killed only about nine thousand people, or that Trump saved two million lives—has been particularly ghastly. Yet millions of Americans believe these claims.

Dinesh D’Souza, the right-wing provocateur who was convicted in federal court in 2014 of making illegal campaign contributions (Trump pardoned him), yet has remained a Christian leader commanding the attention of legions, tweeted on November 9:

There is a great shift under way. We are, all 70 million of us, and our families, going to make our exit OUT of liberal institutions of indoctrination. This means schools, universities, media, entertainment. This won’t happen overnight but it’s happening already. We’re outta here.

One certainly understandable response is: good riddance. But emotions aside, one can see that the process he is describing is already well underway. We may shop at the same big-box stores and eat at the same chain restaurants as the postindustrial, pro-monopolistic market renders the suburban highways of Buffalo indistinguishable from those of Biloxi. But step inside a church or a polling place and you’ll know instantly which part of the country you’re in.

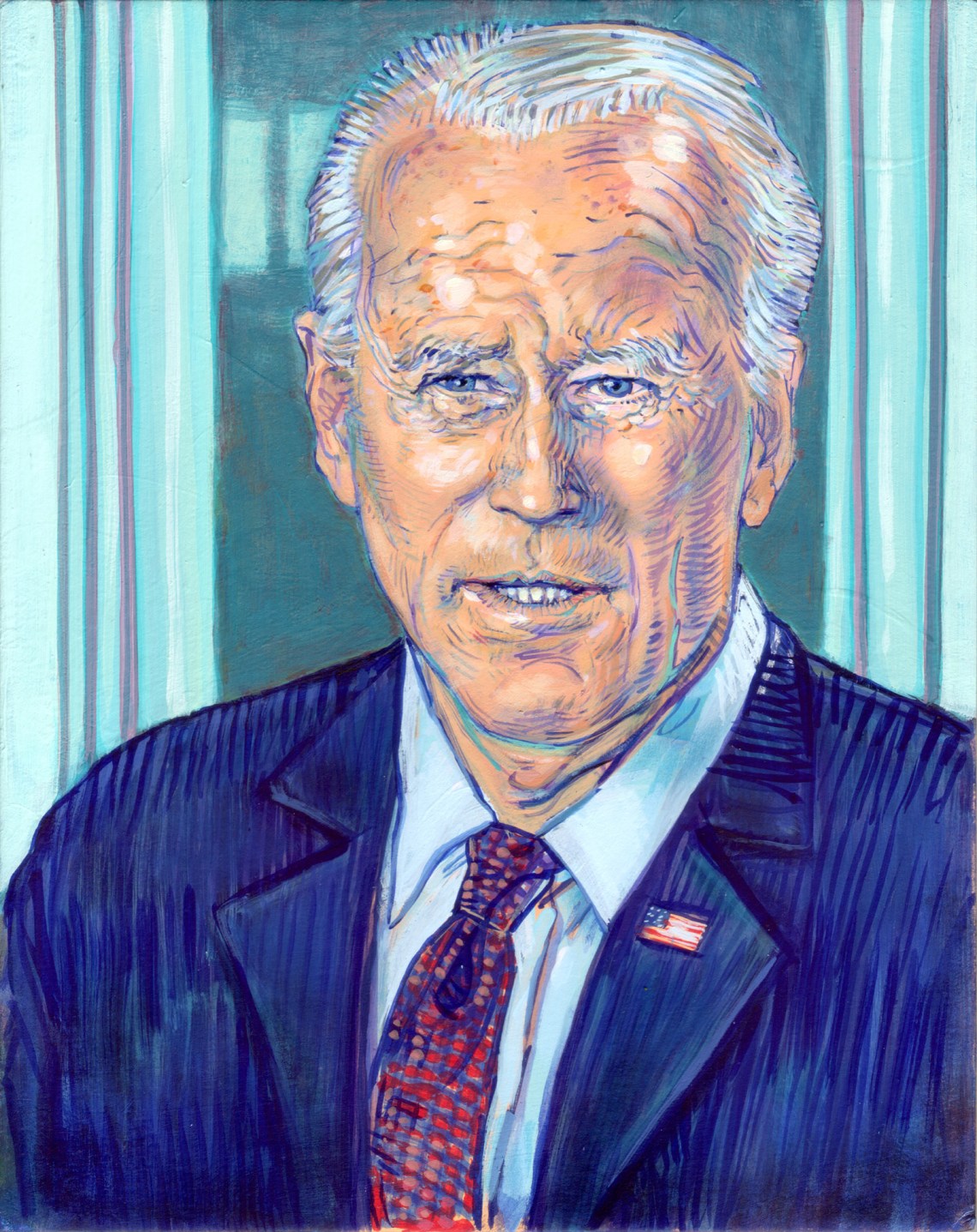

Good things, of course, did happen on election day. Donald Trump was defeated. Fraught and hair-raising though the road to January 20 may be, I’m confident that Joe Biden will take the oath of office and move into the White House. The details of his victory have been dissected thoroughly by now. The heart of it is that he seems to have answered the basic challenge that pundits spent the year laying before him: Could he win over swing voters while simultaneously appealing to the party’s base and to younger, more urban voters? He did. Among independents, according to exit polls, he beat Trump 54 to 41 percent. Trump had beaten Hillary Clinton among them 48 to 42 percent. Biden also did five points better among young voters than Clinton had, winning 60 percent to her 55 percent. He did slightly better among women than Clinton, with 57 percent to her 54 percent.

Advertisement

Trump got a couple more points among Black and Latino voters in 2020 than he did in 2016. It’s hard to say, given the imprecision of exit polls, how meaningful these differences were, but the Trump campaign targeted Black males and certain Latino groups heavily on social media, and the Democrats were slow to respond. For all the media chatter about the Cuban-American vote in Florida, the margins have been essentially static for three elections: Romney got 52 percent; Trump got 54 percent in 2016 and 55 percent this year. Still, that Trump gained anything among these voters should cause Democrats to take serious stock of their failings.

Biden won back the three states that Trump had shocked the country by winning in 2016 by the narrowest of margins: Pennsylvania, Michigan, and Wisconsin. He won Wisconsin by about as much as Clinton had lost it, Pennsylvania by about 25,000 more, and he turned Michigan around decisively, winning it by nearly 150,000 votes. It is especially heartening that Biden won Arizona and Georgia, which no Democrat had done since Bill Clinton in 1996 and 1992 respectively. (Before Clinton, the last Democrat to win Arizona was Harry Truman.) Arizona becomes the fourth state of the Southwest–Mountain West to switch over since Ronald Reagan’s time—in the 1980s, now reliably blue Colorado was as red as Wyoming. This doesn’t mean Arizona is now solidly blue, but it does mean that it will be competitive for the foreseeable future. These are important expansions of the Democratic map.

At the same time, the map seemed to contract in other places. Trump’s victory margins in Ohio and Iowa held steady at around eight to ten points between the two elections, but in Florida, he beat Biden far worse than he beat Clinton, by 373,000 votes this year to 113,000 in 2016. Part of this is explained by the Latino vote. Though the margins among Cuban-Americans haven’t changed over the years, they apparently voted in greater numbers this year than in 2016, enough that their votes helped the GOP capture two Democratic-leaning congressional districts. Trump also did very well among the growing Venezuelan-American population of Florida—helped, perhaps, by a completely false ad his campaign ran claiming that Venezuela’s socialist government was backing Biden. Finally, the effects of the pandemic could have aided Trump’s margin—Republicans did more door-knocking and Trump did more campaigning in Florida, while the Democrats curtailed their activity.

The Democrats didn’t make much effort in Ohio or Iowa, either. But it’s sobering to recognize that none of these three states can really now be called a swing state. For years, Florida and Ohio, with twenty-nine and eighteen electoral votes, respectively, have been the archetypal purple states. Forty-seven electoral votes, votes that have been hotly contested for the last several elections, are a lot for Democrats to leave behind. It gives them little margin for error in future elections in the Great Lakes region and the Southwest.

But at least Biden won. The Senate results were gravely disappointing. Looking over the numbers, I noticed in some states a rather severe drop-off from presidential vote totals to Senate vote totals. In North Carolina, for example, Biden received around 114,000 more votes than Senate candidate Cal Cunningham, who was supposed to be one of those who would lift Democrats to the majority. In Georgia, Biden won about 100,000 more votes than Senate candidate Jon Ossoff; he also received over 850,000 more than Raphael Warnock, but Warnock was running in a special election for Senate against many candidates. In Colorado, even the winning Senate candidate John Hickenlooper received around 70,000 fewer votes than Biden. The pattern was broken in Arizona, where Senate candidate Mark Kelly outpolled Biden by around 44,000 votes.

Kelly aside, these numbers are troubling. There’s often some drop-off below the presidential level, but not usually like this. For example, in 2016, three first-time Democratic Senate candidates won election: Tammy Duckworth in Illinois, Maggie Hassan in New Hampshire, and Catherine Cortez Masto in Nevada. Duckworth and Cortez Masto trailed Clinton by a bit, but the margins were small (Hassan actually outpolled Clinton slightly). One would have to do a comprehensive study to explain this in detail. There are always some local reasons—in North Carolina, Cunningham, for example, was likely hurt by extramarital sexting that became public in early October. But it’s hard to avoid concluding that in several states, swing voters turned against Trump but were loath to endorse a fully Democratic government.

Advertisement

The Democrats’ hopes for a Senate majority now depend on Georgia, where the two runoff races will take place on January 5. Most experts think the odds of a double victory are long. Democrats will need a huge African-American turnout, which Stacey Abrams just might be able to engineer. In the last two years, her organization Fair Fight Action registered some 800,000 new voters. That effort, along with a “motor-voter” law—which was enacted, notably, under Republican governor Nathan Deal, and which automatically registers new drivers to vote—helped make Biden’s win in the state possible. In Fulton and Gwinnett Counties, Black voter registration increased by 40 percent.

Black turnout, in Georgia and throughout the country, was undoubtedly boosted by the presence of Kamala Harris on the Democratic ticket. Warnock, who is African-American and the head pastor at the historic Ebenezer Baptist Church, is well positioned to benefit. He came in first on November 3, but that was because two Republicans split the conservative vote. Ossoff trailed GOP incumbent David Perdue by less than two points. Obama is expected to campaign in the state, as is Harris, and possibly Biden. The Democrats’ message here should be blunt: if we don’t get both these seats, the government will essentially be run by Mitch McConnell. If it’s true that special elections are about motivating the party base, I should think that McConnell is about the most powerful base motivator the Democrats can come up with.

The Senate results were the election’s biggest disappointment, but, in a way, the House results were more shocking. As I write, Republicans have picked up a net eight seats. The Democratic majority is likely to be slim indeed. Predictably, this led to instant recriminations.

Two days after the voting, House Democrats held a caucus meeting at which Representative Abigail Spanberger, a former CIA official first elected in 2018 to represent Virginia’s seventh congressional district—a historically Republican seat—unloaded on the party’s progressive faction. “We need to not ever use the word ‘socialist’ or ‘socialism’ ever again,” she said. “We lost good members because of that.” She pointed to the slogan “defund the police” as a big culprit in Democratic losses, warning that the emphasis risked getting the party “fucking torn apart in 2022.”

This brought a rejoinder two days later from Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, who told the Times that many House Democrats lost in large part because they were running antiquated campaigns and not responding directly to attacks. “They were vulnerable to these messages,” she said, “because they weren’t even on the mediums where these messages were most potent. Sure, you can point to the message, but they were also sitting ducks.”

There is anecdotal evidence supporting the idea that “defund the police” was used effectively in GOP advertising. In Virginia’s GOP-leaning fifth district, Republican Bob Good attacked his Democratic opponent, Cameron Webb, with the declaration, “He’d defund the police, end Medicare, force you into socialized medicine, double your gas prices with a Green New Deal.” The district is an uphill climb for Democrats under the best of circumstances, and indeed a number of the House seats Democrats lost this year were in Republican-leaning districts that Democrats managed to capture in 2018, their best year in House elections since 1974. But those from more winnable districts lost or trailed as well, including, as of this writing, Abby Finkenauer of Iowa’s first district (with a Cook Political Report number of D+1, meaning that it leans slightly Democratic), Rita Hart of Iowa’s second district (D+1), and T.J. Cox of California’s twenty-first district (D+5).1

Democrats are reportedly undertaking a study to determine what worked and what didn’t. But there seem to me two main points of focus. The first is that the “Democratic brand,” to use the phrase some have been bandying about, is in trouble in vast stretches of the country.2 The party must determine why. My hunch is that “defund the police” merely fed into a problem that already existed across exurban middle America, where the Democratic Party is seen as coastal and “too liberal.” (Biden may have laid it on pretty thick with his “Joe from Scranton” bit, but it seems to have effectively established him as a man of the people.)

Second, it would be nice to see the Democrats put more energy into identifying what unites them than what divides them. Nancy Pelosi is clearly hostile to the AOC left, perhaps with good reason, perhaps not. Whatever the case, she is the leader. She should appoint an informal working group that would include leftists, mainstream liberals, and centrists to try to work through their differences. It’s on her to bring the caucus together. This next two-year term may be her last. If she allows the next session to degenerate into an ideological food fight, that will be an unfortunate way for her to go out.

These divisions underline why the Democrats’ failure to capture the Senate—if indeed they fail—is tragic. If they had won the Senate, and if they’d been able to take a vote to reform or eliminate the filibuster—a bigger if, but one on which I was hopeful, provided they’d had fifty-three or fifty-four senators, giving them a few votes to spare—then they could have solved many of their problems by simply governing. They could have passed a coronavirus relief bill; a minimum wage bill; an infrastructure bill; a bill “fixing” Obamacare (protecting it against legal challenges like the one now pending before the Supreme Court) and creating a public option; a voting rights and democracy bill; a bill on climate; a bill for rural America (addressing economic development, rural broadband, the opioid crisis) to keep Biden’s pledge to be the president of those who voted against him as well as for him; an immigration reform bill; a bill on gun safety; and more.

All of these measures are broadly popular among a populace that is, to use Bill Clinton’s old phrase, “operationally progressive and rhetorically conservative.” And all this could have been happening as the nation emerged from the darkness of the pandemic, with broad distribution of the vaccine that Biden promises must be “free to everyone.”3 Americans could have seen something they’ve rarely seen in this century—their government working, passing popular law after popular law, making people’s lives better. Assuming no recession, it all would have made for a 2022 in which Democrats might have expanded their majorities.

Instead, we appear to be headed for two more years of gridlock. McConnell will pass nothing. As for the Supreme Court, not only will Biden not increase its size, which he’s hesitant to do anyway; we may be locked into a situation where Justice Stephen Breyer, now eighty-two, can’t retire and give Biden a chance to put a younger justice on the Court, because McConnell will likely not allow a vote. There will be two years of finger-pointing and nothing getting done, which as McConnell knows will hurt Biden and the Democrats more than the Republicans. Dispirited liberals will stay home in 2022; the Republicans will recapture the House and be well positioned to take back the White House in 2024.

And speaking of 2024, you-know-who vows to run again. Time will reveal to us the precise degree of Donald Trump’s power over the Republican Party once he’s no longer president. Assuming that he continues to make regular public interventions—on Twitter, at rallies, possibly as the star of a new TV network or streaming service—there’s good reason to think that his dominance will last. On Fox News, White House press secretary Kayleigh McEnany, brimming with an enthusiasm not unlike that of a North Korean news broadcaster, observed that the seventy-four-year-old Trump “is the titular head of our party for many decades to come.”

But even if Trump himself fades, it’s hard to see the changes he has effected being undone. No one else will be quite as brazen as Trump, but he and his 73 million votes have taught the party that created him a great deal. Openly being a white ethnonationalist carries surprisingly little penalty, and in fact brings considerable reward. Ditto flouting constitutional traditions and norms—oh, they will eviscerate you on Morning Joe and the Times editorial page, but Amy Coney Barrett sits on the Supreme Court and Merrick Garland does not. You can lie and lie and lie and invert and pervert the truth endlessly, and half of the media and country will be onto you, but the other half will pick up on your cues and rearrange their understanding of the world to suit yours, and together you will fight the other half to a rough draw, even on a matter as serious as the effective negligent homicide of tens of thousands of Americans, if not more.

The Republican Party will not stop doing, or being, all of the above. Its authoritarian impulses, which predate and have enabled Trump, will continue. There is no one in the party—no one—urging it to pull back from the pursuit of total dominance by means of the courts, racial gerrymandering (which it will continue to control), the rules of the Senate, and the imbalance of the Electoral College.

The minority repeatedly thwarting the will of the majority is intolerable and untenable. It will one day lead the Democrats, if and when they have unified power, to take countermeasures that will enrage the minority—watch, for example, Senator Tom Cotton’s angry floor speech from last June against statehood for Washington, D.C. The right will then counter those moves through tactics we haven’t even thought of. The prospect of future disunion is no longer theoretical.

Joe Biden will reset our struggling democracy in some important regards. He will shift away from Vladimir Putin and toward our traditional allies. He will not interfere in Justice Department investigations. He won’t fire his FBI director because the bureau is investigating him. These are not small matters. But what was needed in this election to turn back this dark tide was a much broader repudiation of Trumpism than the voters delivered. It’s not quite mourning in America, but neither is it morning.

—November 18, 2020

This Issue

December 17, 2020

An Awful and Beautiful Light

A Well-Ventilated Conscience

The Oldest Forest

-

1

This is pending the final vote. California always takes a long time to count all its ballots, but as I write, Cox was two thousand votes behind with 98 percent reporting. ↩

-

2

See Joseph O’Neill’s discussion in these pages, “Brand New Dems?,” May 28, 2020. ↩

-

3

See Kate Sullivan, “Biden Says Coronavirus Vaccine Must Be ‘Freely Available to Everyone,’” CNN Politics, October 23, 2020. In essence, the federal government would buy the doses from Pfizer or Moderna (or whomever) and distribute them free of charge. ↩