Over the past two years—since the arrest of Jeffrey Epstein in July 2019 on charges of trafficking minors and then his suicide in prison; Prince Andrew’s calamitous television interview the following November, in which he tried to dissociate himself from Epstein’s crimes but instead brought his public career to an end; and the dramatic arrest in July 2020 of Ghislaine Maxwell, Epstein’s associate and former girlfriend, and her incarceration in a federal prison in Brooklyn—an image has recurred before my mind’s eye. Around ninety years ago a little boy called Jan Hoch, wearing a yarmulke and curled sidelocks, belonged to an Orthodox Jewish community—impoverished, Yiddish-speaking, devout—in the small town of Solotvino in Subcarpathian Ruthenia. His mother wanted him to be a rabbi, and he was destined for the yeshiva in Pressburg (now Bratislava) until war engulfed Europe. Although he escaped, and after many adventures entirely reinvented himself, a horrible fate awaited his family.

That little boy was Ghislaine Maxwell’s father. The story of Robert Maxwell—as Jan Hoch of Solotvino became after he had been variously “Private Leslie Jones,” “Lance-Corporal Leslie Smith,” “Sergeant Ivan du Maurier,” and “Captain Stone”—is so ghastly and so ludicrous and altogether so improbable that it might seem stranger than fiction. There might be echoes from Victorian novels—Mr. Merdle, the “man of the age” before he goes bust in Little Dorrit, or the still more mysterious financier Melmotte in The Way We Live Now—but neither Dickens nor Trollope could quite have invented Maxwell. He was by turns a desperate refugee, a brave soldier, a seemingly successful entrepreneur, a member of Parliament, a newspaper owner, and, as it transpired after his death, an outrageous swindler.

John Preston opens his entertaining and gruesome Fall with a scene earlier in the year of Maxwell’s death. In March 1991 he arrived in New York aboard his yacht, Lady Ghislaine, named after the daughter he had once neglected and bullied but who had become his loyal helpmate and accompanied him on this trip. He was there to pull off what he presented as his greatest coup yet by buying the New York Daily News. Eight months later the yacht was cruising off the Canary Islands with Maxwell aboard until November 5, when he disappeared. Soon afterward, his floating body was found, leaving a final riddle: Accident, suicide, or murder?

This man of mystery was formed by a bleak early life. He was born in 1923, one of the nine children of Mehel and Chanca Hoch, who lived in a two-room shack with a dirt floor. He loved, and was loved by, his mother, but was often beaten by his cruel father, the six-foot-five “Mehel the Tall,” who scratched such living as he could by buying animal skins from butchers and selling them to leather dealers; from him the son inherited his size and maybe his temperament. Much about Maxwell could be understood as a reaction to his childhood, his gluttony and love of luxury set against the poverty and hunger he had once known, his longing for power against powerlessness, maybe even his cruelty to others against the cruelty he had suffered.

Another heritage was his polyglotism. Solotvino lies in a region that during the past hundred and more years has changed hands repeatedly. Between the wars it was at the eastern extremity of Czechoslovakia, having previously been part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire; it then belonged briefly to Hungary, then the Soviet Union, and now is in Ukraine. Its Jews often acquired perforce several languages, and as an adult Maxwell could speak English (very distinctively), French, German, Russian, and Czech. Any religious heritage, on the other hand, he soon shed. Maxwell might be thought almost what the Irish call a spoiled priest, dropping out of the yeshiva and never again entering a synagogue for most of his life.

In March 1939 Czechoslovakia fell apart. Hitler arrived in Prague to declare the Czech rump a Reich dependency, while Slovakia became a puppet state under Monsignor Jozef Tiso, one of the more repellent prelates of that dark age for the Roman Catholic Church, who was later executed as a war criminal. Then in September Germany invaded Poland. Barely sixteen, Hoch managed to flee Solotvino. Many years later he gave one version of his adventures to a hagiographer, claiming that he had walked to Budapest, been imprisoned, and then fought off his warder and escaped, but he was such a fabulist that nothing he said can be accepted with any certainty. At any rate, he seems to have made his roundabout way to France and the exiled Czech army.

There’s no ambiguity about what happened to his family. Before the war had ended, Maxwell’s mother and father, grandfather, and three of his younger siblings were transported to Auschwitz and murdered. For many years Maxwell tried to obliterate this horror, never mentioning his childhood, origins, religion, parents, or their horrible deaths.

Advertisement

In late July 1940, Preston writes, “in French army uniform, carrying a rifle in his hand and unable to speak a word of English, the yet-to-be Robert Maxwell” disembarked in Liverpool. He had just turned seventeen and still wasn’t of military age, but he contrived to join the menial Pioneer Corps, digging ditches alongside more eminent refugees, German-Jewish doctors and musicians. A brief encounter with a woman shopkeeper helped him learn English, although he said that he had already learned it by listening to broadcasts of Winston Churchill’s speeches before he could understand them and absorbing their distinctive tones, which he fondly believed he could emulate.

By 1944 he had joined the British infantry, after changing his name regularly. The Normandy campaign found him as Sergeant du Maurier, from a popular brand of cigarette, leading a sniper section of the North Staffordshire Regiment with enough distinction to win a commission, and by March 1945 Captain Robert Maxwell, as he had finally become, won the Military Cross (MC), pinned on his chest by Field Marshal Sir Bernard Montgomery himself. He went beyond the call of duty in his own way. Maxwell much later described one incident when he shouted in German to enemy soldiers in a farmhouse, “Come out with your hands up. You are completely surrounded.” When they did, “I shot them all with my sub-machine-gun. I thought my boys would be pleased, but all they said was, ‘That’s not fair, sir, those lads had surrendered.’”

In Paris a few months after its liberation Maxwell met Elisabeth Meynard, known as Betty, at a servicemen’s club, swept her off her feet, and married her despite the apprehensions of her prosperous French Protestant family. “Long-suffering” is wholly inadequate to describe a woman who stuck with her monstrous husband until the end despite endless infidelities and scandals. They had four sons and five daughters. Ghislaine, the youngest, was born in 1961, three days before the eldest boy was so gravely injured in a road accident that he spent the remaining six years of his life in a coma. The children were treated horribly by their father, who belittled and humiliated them at every turn. At first Ghislaine was the worst victim, to the point that she was anorexic as a child, but Maxwell relented and she became his favorite, expensively educated at boarding school and Oxford, until Betty could call Ghislaine “spoiled, the only one of my children I can truly say that about.”

If the story of young Hoch’s escape from Solotvino was obscure, Captain Maxwell’s career after the war was also murky. He ended up in Berlin serving in British intelligence, which he may have done for some time after he left the army, while possibly working for other countries’ intelligence services as well. “Later on in life, he could never pass a spotlight without stepping into it,” Preston writes, but at this time, “like Harry Lime in…The Third Man, Maxwell seemed to belong in the shadows, slipping quietly from occupied zone to occupied zone.”

In Berlin he also found the basis of his fortune. He helped run a newspaper owned by Springer-Verlag, which before the war had been the world’s largest publisher of scientific books and journals, and struck a deal with Ferdinand Springer, the head of the firm. By then Maxwell had learned of his parents’ death, but as part of his willful erasure of the past he was quite ready to do business with a man who had prospered under the Third Reich. Springer needed someone who could sell his products internationally, and Maxwell was that someone. By 1948 he had secured world distribution rights to all of Springer-Verlag’s publications. Preston writes that “150 tons of books and another 150 tons of journals were loaded on to a goods train and taken to Bielefeld in western Germany. From there, a convoy of trucks brought them to London,” although the figures seem astonishing.

Soon afterward Maxwell bought into a small trading company, but he required the marketing weight of a larger established publisher, and approached Butterworth, which specialized in medical and legal textbooks. After he created Butterworth–Springer as a subsidiary, he also needed capital, and Major John Whitlock, the head of Butterworth, introduced him to Sir Charles Hambro, scion of a banking dynasty, who “took an immediate shine to Maxwell.” His links to British intelligence may have helped, since Whitlock and Hambro had both served in that twilight world.

In later years not only was Maxwell’s reputation terrible but his personality was repulsive, the embodiment of what his native Yiddish calls grobkeit, boorish and vulgar. But before the passage of time coarsened him he must have been more personable, and for many years a remarkable number of people in the English commercial and financial establishment were taken in by him. With Hambro’s help Maxwell created a British distributor, whose turnover more than doubled between 1950 and 1951, when he changed the name of Butterworth–Springer to Pergamon. Scientific books and journals were a real money-spinner, since universities and libraries needed them, and learned authors didn’t expect to be paid.

Advertisement

Some of the refugees who enlivened London publishing after the war—André Deutsch, Paul Hamlyn, George Weidenfeld—might have been colorful and not always popular with their long-established rivals, but Maxwell was something else again. As he ensconced himself at Headington Hill Hall outside Oxford, Preston says, “darkness—and the whiff of chicanery—was never far away.” Nigel Lawson would one day be chancellor of the exchequer in Margaret Thatcher’s government, but in the early 1950s he was an Oxford undergraduate and found a lowly vacation job working at Maxwell’s warehouse, where he was startled to find that school textbooks rejected as defective in England were being sold in Africa.

For his next move Maxwell went into politics, capriciously choosing Labour, and in 1964 Captain Maxwell added “MP” to the “MC” after his name when he was elected to Parliament as member for Buckingham. The Labour Party didn’t know quite what to make of this “very strange fellow,” as the diarist, former Oxford don, and future cabinet minister Richard Crossman described him: “a Czech Jew with a perfect knowledge of Russian, who has an infamous reputation in the publishing world.” The House of Commons didn’t know what to make of him either, as he became a byword for bombastic garrulity. Completely ignoring parliamentary convention about the length and frequency of speeches, he held forth more than two hundred times in ten months. He was made chairman of the Commons catering committee partly to shut him up, and he soon wrote off the debts of loss-making bars and dining rooms through what was effectively a fire sale, disposing of the cellar of fine wines for far beneath their value, plenty of them ending up at Headington Hill Hall.

Few at Westminster were sorry to see Maxwell lose his seat in 1970, when he returned to his lurid business career. Before floating Pergamon on the stock exchange in 1964 he had created tax-free trusts in Liechtenstein to make his dealings as opaque as possible, but when in 1969 an American firm bid to take over the company, it withdrew its offer after discovering that Maxwell had inflated sales and profit figures. By 1971 inspectors from the Department of Trade and Industry had scrutinized Maxwell’s affairs and published a report describing him as “not…a person who can be relied on to exercise proper stewardship of a publicly quoted company.”

It might seem extraordinary that he could have continued in business at all after that. But Maxwell wasn’t called “the bouncing Czech” for nothing, and soon he bounced back, with his new ambition to become a press magnate. He had already tried and failed to buy the Sun (formerly the Daily Herald, and the voice of the Labour Party) before attempting to buy News of the World, that monument to English salacious prurience. “It would not be a good thing for Mr. Maxwell,” said the editor, Stafford Somerfield, “formerly Jan Ludwig Hoch, to gain control of…a newspaper which I know is as British as roast beef and Yorkshire pudding.” Those distasteful words had an unintended effect, quickening the interest of a young entrepreneur who was as British as roast wallaby. Rupert Murdoch pounced, and his acquisition of News of the World in 1968 began his adventure as a London media mogul. It also began a comical rivalry that lasted more than two decades, in which Maxwell was always outplayed by Murdoch. He thought he was fighting another boxer, the late Harold Evans observed, when “in fact, he’d entered the ring with a ju-jitsu artist who also happened to be carrying a stiletto.” Whatever else one thinks of him, Murdoch was a formidable operator, whereas Maxwell was always a sham.

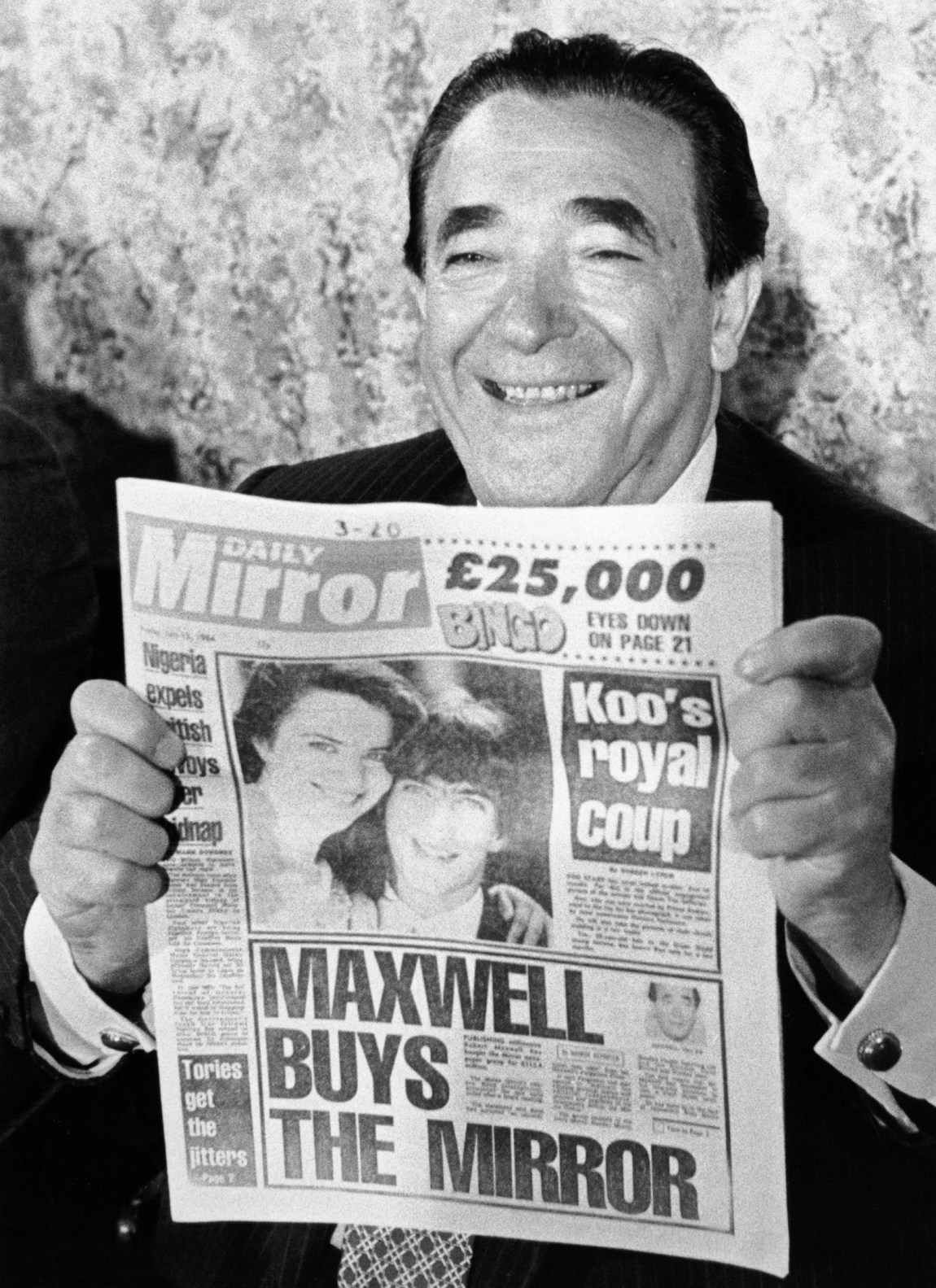

And yet bouncing on he went, fending off criminal charges all the while, and by 1981 he had acquired control of the British Printing Corporation, until recently the largest printing group in the country, which he renamed the Maxwell Communications Corporation (MCC). In 1984 he achieved what seemed a real triumph by buying the Daily Mirror. In its midcentury heyday it had been a great popular newspaper that had won the circulation war as the first true voice of the English working class, and it was still the second-best-selling paper in the country after Murdoch’s Sun. I was in San Francisco for the Democratic Convention when news of the sale reached us, and a group of English scribblers repaired to a bar near Union Square, where Keith Waterhouse, a veteran Mirror columnist, danced a little jig mocking “Cap’n Bob,” before he escaped to the Daily Mail.

What happened next was no laughing matter. Or rather, Maxwell became a bad joke, as he turned the paper into a vehicle for his own glorification, with his face continually appearing in its pages and his fatuous opinions trumpeted. The staff shuddered at his profane and abusive tirades, shouted over the vast coffee cup on his desk that bore the motto “VERY IMPORTANT PERSON.” He nevertheless found people ready to do his bidding. Roy Greenslade would later write in haughty tones about media matters for The Guardian while clandestinely helping the terrorist Irish Republican Army, as he has recently admitted, but he had earlier served as Maxwell’s editor of the Mirror, and at his behest rigged the competitions in the paper so that the prizes offered would never be won. Before Alastair Campbell became Tony Blair’s spin doctor and helped orchestrate the war of lies that preceded the invasion of Iraq, he also worked for Maxwell. Joe Haines, formerly press officer to Harold Wilson at Downing Street, wrote a ludicrously heroic “official biography” of Maxwell, and Peter Jay, who had been the British ambassador in Washington, became his “chief of staff.”

In 1986 the Thatcher government drastically deregulated the financial markets of the City of London, which was meant to lead to a new golden age of vigorous competition, as was similar deregulation of Wall Street. What ensued was a weird era of reckless casino capitalism, with dazzling innovations like credit default swaps and subprime mortgages, all leading to the crash of 2008. But there was a foretaste of that by way of Maxwell. By the late 1980s his vaunted business empire was in deep trouble, requiring one surreptitious expedient after another to disguise its grave condition. In the hope of cleansing his name Maxwell offered numerous charitable donations—for AIDS research, for starving Ethiopians—but somehow the promised funds rarely arrived.

And yet still the banks—forty-four of them at one point!—lined up to lend him money. They accepted MCC stock as collateral, requiring more stock to be transferred if the share price fell below a certain point, not bothering to wonder whether the price had any real meaning. In fact, while Maxwell was servicing his debts by mortgaging stock (“pig on pork,” as the term of art has it), he was inflating that price by buying MCC stock with money he first borrowed, then stole. As he edged ever closer to the brink he used the oppressive English libel laws to silence critics, notably Private Eye, but when in July 1990 the Financial Times took a hard look and said that shares in his company were essentially worthless, he didn’t dare sue.

Nor was his next (and last) victory all he claimed. By the time Maxwell proudly bought it, the Daily News was near collapse, with circulation plummeting, production controlled by the unions, and distribution controlled by the mob. There was one moment of comic relief when a print union negotiator said that Maxwell seemed “like an English nobleman,” a unique estimation. An even better one came when he insinuated himself into a Washington lunch party where he sat next to President George H.W. Bush and loudly held forth on world affairs. As the bemused Bush left he could be seen mouthing, “Who was that guy?” Funniest of all was when Maxwell ordered Jim Hoge, the publisher of the Daily News, to ring Murdoch in the middle of the Australian night and say that he had bought the paper, at which Murdoch burst into laughter and thanked Maxwell for being so helpful.

Shortly thereafter came his mysterious death. An autopsy showed that he had been alive for hours in the water and may have desperately clung to the boat before his heart gave out, which could suggest an accident, but he had good reason to end it all. And enough was already known about him to make the tributes he received quite grotesque. The recently deposed Thatcher said that Maxwell had shown the world “that one person can move and influence events by using his own God-given talents and abilities,” the Labour Party leader Neil Kinnock called him “one of the few people I have known who deserved to be called irreplaceable,” while Mikhail Gorbachev was “deeply grieved.”

And then the shattering truth emerged. Maxwell’s whole operation was fraudulent: it collapsed with debts of several billion pounds, with the banks that had accepted stock as collateral losing £655 million. Worst of all, the desperate Maxwell had looted £429 million from his companies’ pension funds, including the Mirror’s.

Nothing in this story is so strange as Maxwell’s identity, or what he made of it. He transformed himself into his version of an English—or Scottish—officer and gentleman. About five years before his death, he was dining in Edinburgh with Ian Watson, one of his editors, when the floodlights silhouetting Edinburgh Castle against the night sky came on. “Look, Watty,” Maxwell said, “there’s a sight to warm the hearts of true Scotsmen like you and me!” Watson thought he was joking: “It took a few moments for me to realize Maxwell was being completely serious.”

When he was elected to Parliament in 1964 Maxwell was called by the Jewish Chronicle, which likes to take note of Jewish achievements, including the number of MPs. “I’m not Jewish,” said the sometime yeshiva boy, and put down the telephone. Twenty years later, in the witness box at one of his court cases, he tearfully recalled his mother’s death in Auschwitz, which cynics thought a convenient turn at a time when he wanted sympathy. But his belated acceptance might have been prompted by his personal disintegration, or maybe intimations of mortality.

Did he try to come to terms with the past he had so long concealed? He had begun giving—or at least promising—money to Israeli charities, and when he died no one was more fulsome than Shimon Peres, the former prime minister and future president of Israel, who called Maxwell “not a man but an empire in his power, thought and deeds.” Before the awful truth became known, his body was taken to Jerusalem and given something like a state funeral on the Mount of Olives. A kind of homecoming for the little boy from Solotvino, or a last macabre joke?