Bong Joon Ho’s film Parasite (2019) unfolds in two of the most memorable domestic spaces in recent cinema: the Kim family’s squalid apartment, on a Seoul street prone to fumigation and floods, and the tech entrepreneur Nathan Park’s sleek modernist mansion, which the grifting Kims infiltrate. In a delirious twist halfway through the movie, Bong reveals that the Park home, like similar structures built within living memory of the Korean War, has a “secret [bunker] where you can hide in case North Korea attacks or creditors break in.” (Neither Communists nor capitalists can be trusted.) Parasite imagines contemporary Korea as a haunted house, where rigid lines—between haves and have-nots, the present and the past—are broken in shocking fashion.

The mansion was designed and originally inhabited by a world-famous architect, Namgoong, who left Korea after the place was sold to the Parks some years earlier. The fictional Namgoong perhaps figures as Bong’s alter ego: the absent, godlike designer of the drama and chaos unfolding on-screen. Parasite and its structures came forcefully to mind recently as I read a new English-language collection of work by Yi Sang, Korean literature’s perpetual enfant terrible. Yi Sang was not only a cutting-edge writer but a working architect, and his oeuvre teems with dark rooms, mirror worlds, and other uncanny spaces.

In 1929, at age nineteen, Yi Sang won a contest to design the cover of a magazine for Japanese architects in Korea. Two years later, his first poetic sequences appeared in that publication, with industry-appropriate titles like “Solid Angle Blueprint” and “Bird’s Eye View.” The poem “Movement” suggests Gertrude Stein vanishing into an Escher print:

I climb up above the first floor to the second floor to the third floor to the rooftop garden and look to the south and there is nothing there and look to the north and there is nothing there and so I go down from the rooftop garden to the third floor to the second floor to the first floor…

Still others use the language of geometry and physics—grids, equations, an “azimuthal study of numbers,” even actual shapes—to disorienting effect. Logical statements collapse into nonsense or sorcery. The mostly mathematical “Memorandum on the Line 3” ends with a glimpse of the reader’s blown mind: “The brain opened into a circle like a folding fan, then rotated completely.”

A more tangible space opens up in Yi Sang’s best-known story, “Wings,” published when he was twenty-six, less than a year before his death. The unreliable narrator resides with his wife in room 7 of House No. 33, where “eighteen households live side by side,” the residents “young as blossoms.” Though he notes the building’s similarity to a “house of pleasure,” his insight stops there. The layout of the couple’s pad limits true knowledge of his marriage: “The sliding door dividing the room in half symbolized my destiny,” he reflects, and his wife berates him if he sets foot in her territory. At the end of this Poe-like tale, upon realizing his wife is turning tricks, he flees home (or the brothel), tears through the streets of Seoul, and heads for the roof garden of the Western-style Mitsukoshi department store, from which he does or doesn’t jump.

“Have you ever seen a stuffed genius?” quips the narrator at the start of “Wings.” Yi Sang’s ghost might claim such status today, if only we could agree on what we’re seeing. He is at once enigmatic outlaw and culture hero, whose work crystallizes the anxieties of Korea under Japanese rule in the first half of the twentieth century. Though he is chiefly known as a poet, his hard-to-categorize prose—in the form of autofictional stories (“Encounters and Departures”), impressionistic essays (“Ennui”), and playful nightmares (“Deathly Child”)—is also revered. A top prize for South Korean fiction, established in 1977, bears his name. Recipients include Han Kang, whose Man Booker Prize–winning novel The Vegetarian (2007) was sparked by a line from Yi Sang’s notebooks: “I believe that humans should be plants.” That a single dusty sentence could help conjure a feminist landmark seventy years later is a testament to his peculiar talent.

In America, there have been two notable gatherings of translations and commentary. In 1995 Walter K. Lew edited a lavish seventy-page portfolio of Yi Sang’s poetry, prose, and visual art for the first issue of Muae, a short-lived “journal of transcultural production.” For Lew, Yi Sang’s “architechtonically precise pieces” drip with forbidden sexual content, and the accompanying academic critiques are aptly provocative, teasing out the horny in the cryptic.1 In 2002 Myong-Hee Kim translated fifty-five of his poems and stories (which she likens to essays) in Crow’s Eye View: The Infamy of Lee Sang, Korean Poet. (The title uses an alternate anglicization of his name.) For her, his life was essentially tragic, his interior quests akin to those of Franz Kafka.

Advertisement

Now there is a generous Selected Works, edited by the poet Don Mee Choi. Although it doesn’t include “Wings” or “Encounters and Departures” (both of which are excerpted in the earlier books), it fills in other parts of the portrait. In “Yi Sang’s House,” an essay included in the book, Choi calls his output a form of “literary resistance to the Japanese colonial rule,” his stories “essentially colonial fairy tales.”2 She connects his plight with her own relationship to English and the United States (of which South Korea, after World War II, has been a “neocolony”), and casts his work as a precursor to her poetry, especially her National Book Award–winning collection, DMZ Colony (2020).

The sheer range and convoluted publishing history of Yi Sang’s work make any selection a challenge. Chronology, language, and genre get tangled—a fitting mess for a writer who refused to behave. His brief life was one of contradiction, scandal, and puzzling swerves. He was born Kim Hye-kyŏng in 1910, barely a month after the Korean emperor had signed over the kingdom to an ascendant Japan. Korea remained a Japanese colony until the end of World War II, meaning the poet’s entire life was spent as a man without a country. His father became a barber after losing three fingers while working as a printer for the Royal Palace—a perfect symbol for the amputation of Korean sovereignty.

At three, Kim Hye-kyŏng was adopted by his father’s older brother, who was childless—a not uncommon practice of the time. (His birth parents went on to have two other children.) His uncle’s wealth enabled him to attend elite schools. At sixteen, he entered the prestigious Gyeongseong Technical College (later part of Seoul National University) to study architecture. He was one of just two Koreans in his grade. According to Myong-Hee Kim, at a sixty-year reunion a Japanese classmate remembered him as “always being at the top of his class,” as well as a cut-up who made everyone laugh.

A vertiginous exchange in the memoir-story “Encounters and Departures” gets at this double identity. Someone named Kin Sang hails the narrator: “It’s been a long time, Kin Sang.” The narrator explains that “he addressed me as Kin Sang because, in truth, Yi Sang is also Kin Sang.” The doubling makes eerie sense, as “Kin” was Japanese for his birth name, Kim. (“Sang” is close enough to the Japanese “san” to render this as “Mr. Kim.”) In life, he was Korean but not Korean, a son but not a son. At school, the instruction was in Japanese: “With the tuition my parents paid, I only learned words they don’t understand.” After graduation, he worked as a draftsman for the Japanese governor-general’s office, “focus[ed] on the urbanization of the colonial capital”—Seoul, or Gyeongseong, renamed Keijo.3 It was at once a practical career path and a literal embedding into the imperial structure.

At Gyeongseong, Kim Hye-kyŏng took the pen name Yi Sang. His reasons are unclear. Jack Jung, the excellent translator of most of the Korean material in Selected Works, notes that Kim signed a yearbook with this handle in 1929, and cites a theory that it was “to honor a gift given to him by a fellow painter friend at the same school…a painter’s box made out of plum wood.” Korean names traditionally have a second spelling in Chinese, beyond the phonetic one in the Korean alphabet; the theory proposes that the specific Chinese characters for yi and sang correspond to “plum tree” and “box.” The friend in question, Gu Bon-woong, would have been one of just a few fellow Koreans at the school. Might the new name secretly acknowledge their shared heritage? Another theory, elegant if unprovable, was devised by Walter Lew in Muae: Jean Cocteau was popular in Japan, regularly discussed in journals that the young Korean cineaste was aware of. Could it be that when Cocteau’s Le sang d’un poète (The Blood of a Poet) was shown in Seoul circa 1930, Kim Hye-kyŏng saw the title as “Lee Sang, a poet,” and adopted it to honor one of his heroes?

A simpler explanation lies in the name’s Korean homophone: yisang—strange. “Everything was strange to me,” confesses the deluded narrator of “Wings.” And nearly everything Yi Sang wrote is strange to the general reader, from his math-driven early poems (written in Japanese) to the confounding late prose (including the claustrophobic “Spider & Spider Meet Pigs,” originally printed without spaces between words). Even his pastoral sketch “A Journey into the Mountain Village” is a paean to modernism, the urbane voice impatient to connect with technology and culture: “I dream about a city girl who looks like the logo of Paramount Pictures.”

Advertisement

Part of the strangeness comes from Yi Sang’s swift intake of foreign matter. His writing is sprinkled with allusions to Oscar Wilde and Maxim Gorky, Al Capone and the Jean Arthur caper Adventure in Manhattan. He kept tabs on Japanese practitioners of the literary school Shinkankakuha (“new sensibilities”) and was receptive to the avant-gardes out of Europe: Futurism, Dada, and Surrealism. His project was to take these continental models and their Japanese adaptations and find space for a uniquely Korean consciousness.

In 1931 Yi Sang contracted tuberculosis while working at a building site. During the six years left to him, his poetry turned into a hall of mirrors, with all manner of body horror lurking around the corner. Limbs sprout limbs, cups resemble skulls, razored-off arms form a candelabra, and lungs develop appendicitis; demonic dolls, prosthetic legs, paper tombstones, and bungled suicides accumulate. “My body’s flesh is now never at home,” he wrote in 1933. Verse was his “autographed obituary.” A self-portrait from this time shows him gaunt and stubbled, with “wild, bird’s nest–like hair.”

In “This Kind of Poetry” (1933), he works TB into a symbol. With wide gaps like gasps, he revisits the fateful site where disease befell him:

While digging ground for

construction I found a big

stone and looking at it made

me think it was shaped like

something from before

Workers carry the stone to the side of a road. Overnight, it dissolves in the rain. Yet he can’t shake its presence, writes a strangely romantic ode to it, feels the pain anew in his words. “This kind of poetry,” he concludes, “I just wanted to rip it apart.” TB becomes the weather of his life, colonizes the lungs of his poems. “I have swallowed up all the painful pronunciations,” he writes in “Fortunetelling.” The speaker of “Path” is practically immobilized:

My story is this suffocating walk. My coughs are the punctuating marks made by my shoes…. I walk for about a page…. After loud laughter, a pungent ink is spilled over my taunting face.

Along with sickness, sexual obsession defined Yi Sang’s remaining time. In 1933 his illness worsened, and he quit his job at the governor-general’s office, going to a hot springs to recuperate. This experience kicks off “Encounters and Departures,” which begins like noir: “I’m twenty-three, it’s March, and I’m coughing up blood.”

While convalescing, “Yi Sang” meets a kisaeng (a courtesan typically accomplished in music, poetry, and dance) named Kŭm-hong—also the name of the kisaeng who consumed him in real life. From the beginning, they misjudge each other. Kŭm-hong is twenty-one but the narrator thinks she looks “sixteen, nineteen at the most” and behaves with the maturity of a thirty-one-year-old; she thinks the narrator might be as old as forty, although he sometimes acts like a boy of ten. He tries to pass her off to others (including a character assumed to be his friend Gu, of plum-wood box fame); when they finally sleep together, “the force of passion seemed to hold back the blood in my lungs.”

Is this love? The narrator doesn’t pay Kŭm-hong. “It didn’t bother me when I caught a glimpse of their shoes side by side on the doorstep of the place,” Yi Sang writes of her clients—a scandalously complacent attitude that he later turned on its head in “Wings.” Kŭm-hong moves with him to Seoul, where they “blissfully cuddled together in marriage,” though in actuality they never officially wed. In real life the pair ran a teahouse called Jebi (Sparrow), a hangout for writers and artists, which lasted until 1935. His novelist friend Pak T’ae-wŏn captured the milieu in fiction: “Jobless types are sitting around on cane chairs, talking, drinking tea, smoking cigarettes, and listening to records.” According to Myong-Hee Kim, Pak noted that Jebi was “furnished with tables and chairs half the normal size,” with a single painting on the wall: Yi Sang’s self-portrait.

“Encounters and Departures” elides the Jebi venture, jumping to the couple’s breakup in 1935. In between—specifically, the summer of 1934—is when Yi Sang rose to the height of his literary powers, fueled by his unorthodox ménage and the camaraderie of the literary group Kuinhoe (Circle of Nine), formed in 1933. With the help of fellow members Pak T’ae-wŏn and Yi Taejon, he serialized in the Chosun Central Daily newspaper what became his signature work, “Crow’s Eye View”—a proposed series of thirty poems (only fifteen of which were published) that he claimed to have chosen from a sea of two thousand. Unlike his previous “Bird’s Eye View” sequence, these were written in Korean rather than Japanese.4

The first “Crow’s Eye View” poem appeared on July 24. It begins cinematically: “13 children speed toward the way,” in Jack Jung’s translation. Are they running to or from something? The poet reports “The 1st child says it is scary,” a line that repeats with the second, third, and fourth child, all the way up to the thirteenth. As in “Movement,” Yi Sang takes the reader through every step; here, the effect is menacing. The relentless classification continues: “Among 13 children there are scary children and scared children and they are all they are.” The number 13 isn’t unlucky in Korean culture, but it might as well be after this poem.

The next day two more installments were published—a pair of verbal vortices. The first starts, “When my father dozes off beside me I become my father and I become my father’s/father and even then my father is my father”; the other, “The one who fights is thus the one who hasn’t fought and the one who fights has also been the one who doesn’t fight.” Each set of five lines ends with a dash, multiplying to infinity, as if the poet has put a mirror before a mirror—twice.

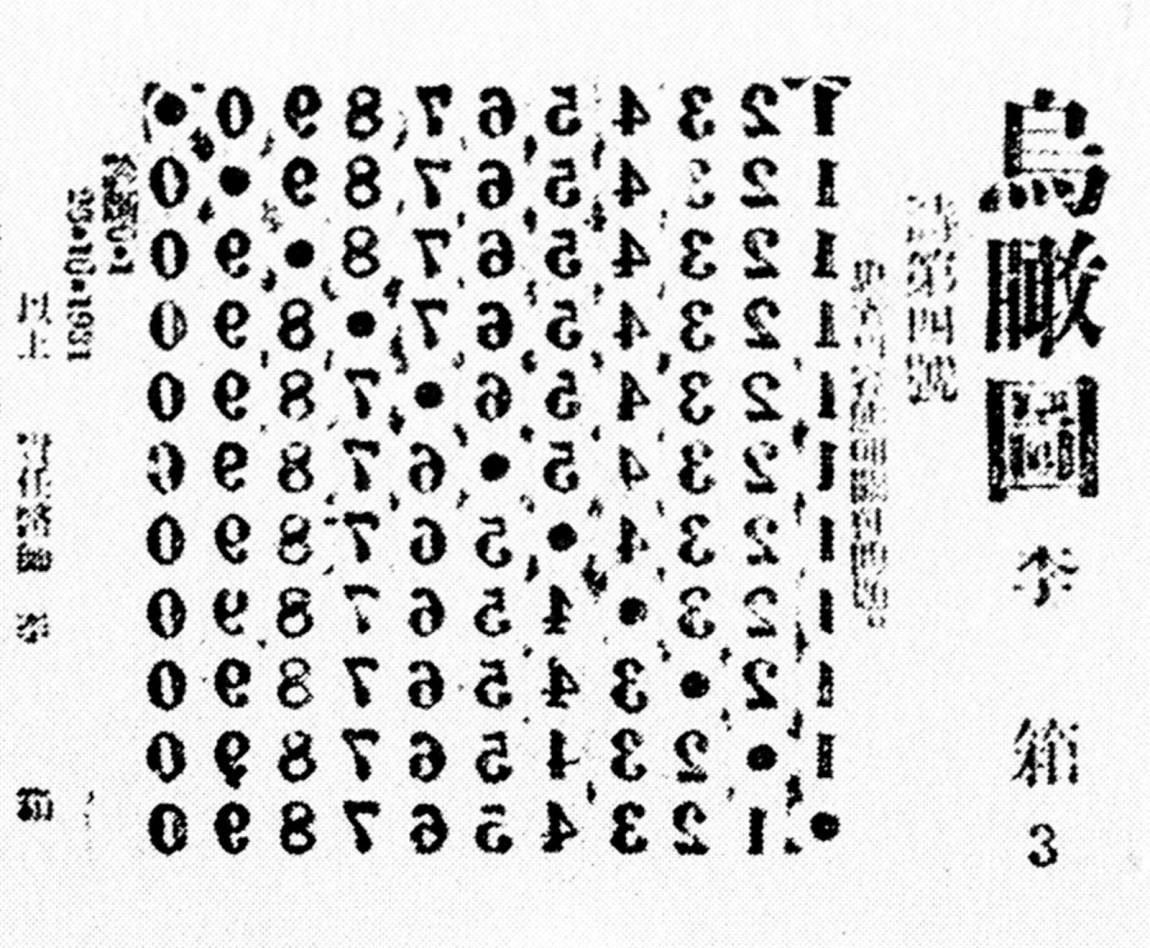

Readers waited three days (July 28) for the next weird set. “Poem No. 4” announces that there’s a “Problem concerning the patient’s face,” and then presents eleven rows of digits, 0987654321, cut diagonally by a string of dots and printed backward.5 A diagnosis sits at the bottom (“0:1”), given by “primary doctor Yi Sang.” “Poem No. 5” is also graphically bizarre. Immediately below the line “This is an old tale of a man collapsing before a short, fat god” is a rectilinear drawing, its left side imploding, the two stubs resolving into arrows.

“Poem No. 6,” a fractured fairy tale with a “birdie parrot” and “2 horsies,” appeared on the last day of July. “Is this little girl gentleman Yi Sang’s bride?” the parrot (I think) asks. Yi Sang is banished, his frail body knocked off its “axis.” The word “sCANDAL” appears, in strangely capitalized English, as though lit from within. “Poem No. 7” (August 1) appears relatively straightforward, albeit with dots separating the high-Symbolist sentences. But Yi Sang was back to being yisang in “Poem No. 8,” literally an experimental poem, complete with a table of instruments and variables (“Silver mirror [=] 1,” “Temperature [=] Nonexistent”). The narrator of “Poem No. 9” (“Muzzle”) feels sweat pool in “the ecstatic valley of my fingerprints” as the barrels of two guns enter his body, one in each end.6

Six more poems followed, with more mirrors and broken bodies and bullets. After “Poem No. 15,” the newspaper halted publication of “Crow’s Eye View,” heeding its outraged readers. “Stop this madman’s ravings!” one demanded. Another threatened to burn the poems in front of the office. Yi Sang drafted a scathing letter that never ran: “Why do you all say I’m crazy? We are decades behind others, and you think it’s okay to be complacent?… I pity this wasteland where I can hear no echo for my howl!” He’s the bringer of light, castigating his ungrateful audience. “I won’t ever try something like this again,” he sighs, adding ironically, “I will study quietly for a while, and in my spare time try to cure my insanity.”

In Korean lore, the crow has prophetic powers, and a three-legged version (samjogo) appears in ancient symbology. But it’s conceivable that Yi Sang was looking outside Korea for a title. The scholar Yoon Jeong Oh notes that the visionary Swiss-born architect Le Corbusier was featured in a 1929 issue of the architecture magazine for which Yi Sang designed a cover that same year—which went on to publish his first poems.7 Born Charles-Édouard Jeanneret, Le Corbusier took his professional name from the French word for crow or raven—an all-seeing creature for a new age.

When Yi Sang titled this series of poems “Crow’s Eye View,” he might have meant to align himself with Le Corbusier, able to take in and reconfigure the literary landscape just as the architect could transform a city. His “madman’s ravings” could be sketches for a new mode of consciousness. The strange lines of his aborted project resonate with the declarations Le Corbusier set down soon after in Aircraft (1935): “THE EYE NOW SEES IN SUBSTANCE WHAT THE MIND FORMERLY COULD ONLY SUBJECTIVELY CONCEIVE…. MAN WILL MAKE USE OF IT TO CONCEIVE NEW AIMS. CITIES WILL ARISE OUT OF THEIR ASHES.”

As public furor mounted over “Crow’s Eye View” in the summer of 1934, Yi Sang’s skill as a visual artist was on display in a different newspaper. Pak T’ae-wŏn’s A Day in the Life of Kubo the Novelist was serialized in the Chosun Chungang Daily from August 1 to September 15, accompanied by twenty-eight striking illustrations by Yi Sang under the pseudonym Hayung.8 At first blush, they resemble movie storyboards. Bits of Korean, Chinese, and English lettering (“COME HERE”) ornament some panels. Yi Sang found ways to render the pleasures and cacophony of the city, and also make heroic the main character’s mission—at once everyday and grandiose—to write something. The first image depicts a hand holding a pen, in between a woman’s face and a pair of shoes, all of it floating above sheets of paper that resemble building façades, or façades that resemble paper.

Pak was born in Seoul in 1909 to a “significantly Westernized family,” according to his son, and was apprenticed to Yi Kwang-su, Korea’s first major modernist writer. (Yi helped draft the Korean declaration of independence, which was read aloud at mass demonstrations on March 1, 1919.) While still in high school, Pak translated Ernest Hemingway and Katherine Mansfield. Like his mentor, he went to Tokyo to further his education and immerse himself in the city’s cultural life, but returned to Korea after a year and a half.

Pak’s novella has a sunny plotlessness that’s a joy to read: Mr. Kubo, a twenty-six-year-old still living with his mother, sets out one morning to wander the city. He runs into friends, falls into reveries, engages with dogs that don’t like him. He’s a highly relatable modern type: artistic and self-doubting, torn between tradition and his individual needs, outwardly pleasant and inwardly judgmental (“Kubo feels a strong impulse to regard all people as mental patients”). He grows neurotic about his lackluster love life and his health: “Of course, the problem wasn’t just Kubo’s left ear. He hadn’t much confidence in his right ear either.” We get a crow’s-eye view of his stream of consciousness, the comedy occurring at a slight elevation.

The state of being a writer and not writing weighs on Kubo. He justifies talking to a painter because “a novelist requires all kinds of knowledge”; though he has no set destination, he’s moved to “go somewhere…for the sake of my writing.” At one point, a friend praises Joyce’s Ulysses, and though our hero sniffs that “novelty alone is not a just cause for praise,” A Day in the Life itself is an underappreciated Eastern response to that colossal novel—the floating life compressed into a single day.

In Yi Sang’s “True Story—Lost Flower,” a nine-part suite that pays homage to his Circle of Nine pals, he winks at Pak: “Mr. Kubo the writer says—add cream to coffee and it smells like rat piss.” Yi Sang himself is captured movingly in Pak’s pages. Kubo stops by the poet’s teahouse and the two dine on oxtail soup despite the heat. He wanders solo and returns hours later, at which time he’s accosted by a former classmate (now in insurance), who grills him on how much money novelists make. To Kubo’s relief, his poet friend appears. The “poor novelist” Kubo considers their poverty: “In times like these, even running a small teahouse isn’t easy. Three months unpaid rent.” They have a night on the town with some barmaids, but Kubo is overcome with sadness, fretting over his mother and his writing. He departs with every author’s famous last words: “Tomorrow…from tomorrow, I’ll stay home, I’ll write…” “Write a good novel,” his friend says, “with real sincerity,” and the book ends on a hopeful note.

“Encounters and Departures” describes a final brief reunion between Yi Sang and Kŭm-hong, as the writer and the kisaeng drink and sing songs from the northwest and southwest—areas that, less than twenty years later, were separated by the DMZ across the 38th Parallel. (To be precise, the songs are from Yongbyon, the area today known to house North Korea’s nuclear facility.) Is it too much to see this north/south medley, or the demarcated prostitute’s room in “Wings,” as harbingers of the country’s division? “Encounters and Departures” ends with exhilarating abruptness, as Kŭm-hong launches into an unfamiliar tune: “It is but a dream to deceive…/Set fire to your shadowy heart—”

In 1936 Yi Sang’s sister eloped with her lover to China; in “A Letter to My Sister,” never sent but published as a magazine article, he admires her bravery in leaving without seeking parental approval. Shortly after, he married Pyŏn Tong-rim, the sister of a friend. But by year’s end he had impulsively moved from Seoul to Tokyo alone—the only time he ever went abroad. In a scabrous essay on the Japanese capital, he vents about the rackety spirit and bad smells of his surroundings, complaining that “people with barely functioning lungs like myself have no right to live in this city.” To punctuate his disappointment, he defecates in a public toilet while reciting the names of Korean friends who boasted about visiting Tokyo.

Though the essay didn’t appear in his lifetime, one can imagine Yi Sang broadcasting such sentiments in conversation, attracting police attention. In February he was jailed on the vague charge of “thought crime,” and his tuberculosis worsened behind bars. Released after a month, he died on April 17, 1937, a day after both his father and grandmother passed away. His wife brought his ashes back to Korea, but their whereabouts are unknown.

The shape of Yi Sang’s brief life feels fated: an architect leaves home and dies in a foreign land. A product of Japan as well as Korea—someone who could make his Japanese classmates laugh—he is martyred for his ethnicity. In his essay “After Sickbed,” he writes in the third person about intimations of immortality upon first coming down with TB:

As he was getting nearer to his biological death, his heart filled with burning hope and ambition. His consciousness recovered. He felt throttled by an energy that he hadn’t tasted in a long time…. Though his body became more and more emaciated, he was sure that his body was made of iron. It could never die.9

Improbably but inevitably, his legacy lives on. Like Keats in the previous century, Yi Sang died of tuberculosis in his mid-twenties with a lifetime of promise cut short. Like the American horror writer H.P. Lovecraft (who died just a month before Yi Sang), he was a writer of such charisma that although he never published a book of his own, his loyal friends burnished his legacy. The Circle of Nine resolved to “gather his blood-stained manuscripts and present them to the new generation the poet wanted so desperately to be friends with,” in the words of Kim Kirim, whose book of poems Yi Sang had edited and designed.

According to Myong-Hee Kim, there was once a rumor that Yi Sang’s brother-in-law, Pyŏn Tong-uk, fled to North Korea with a trove of unpublished poetry—perhaps the two thousand verses from which Yi Sang selected “Crow’s Eye View.” Yi Sang’s widow flatly denied this: “My brother could not have possessed any poems unknown to me.” The fantasy that hundreds of heretofore unseen poems might emerge in North Korea is irresistible: the poet attaining an afterlife, like the secret existence he sometimes pictured on the other side of the mirror.

Or perhaps his story was being conflated with the fate of his artistic brother-in-arms, Pak (or Park) T’ae-wŏn. Thirteen years after Yi Sang’s death, just before the Korean War erupted in June 1950, Pak traveled north with a literary delegation. The war prevented his return. Did he mean to defect all along? According to his son, Daniel, the invading North Korean army forced Pak’s wife, still in the South, to work for a Communist organization, which landed her in jail after the war. Pak T’ae-wŏn continued his literary career in the North, writing historical novels. He never returned to the South, where his books were banned into the 1980s, and died in 1986. His wife in Seoul—Daniel’s mother—was released from her life sentence after five years, a shell of her former self.

“Is the ending to the story good enough as it stands?” Mr. Kubo once asked himself. If you believe in the transmission of genius, Pak T’ae-wŏn’s legacy has a modern-day finale, just as a cutting from Yi Sang’s notebook reached out across the decades and found flower in Han Kang’s The Vegetarian. Because what happens next is that Daniel’s sister, Pak So-young, marries a man named Bong Sang-gyun, a graphic designer. They have four children, the youngest of whom goes on to direct the first foreign-language film to win the Oscar for Best Picture, seventy years after his grandfather disappeared in the North—a haunted-house story called Parasite, about an architect who has left the country.

This Issue

October 21, 2021

The Storyteller

‘Who Designs Your Race?’

Are the Kids All Right?

-

1

For example, Ma Kwang Soo decodes the numerals 1 and 3 (in the 1934 Yi Sang poem beginning “Thirteen kids make a mad dash down the street”) as a penis and a “female’s breasts and buttocks.” The digits’ presence in an earlier poem, which repeats the equation “1+3,” therefore represents sexual congress. ↩

-

2

The omission of “Wings” and “Encounters and Departures” is curious. Perhaps their first-person depictions of men married to prostitutes make them harder to classify as colonial fairy tales—though the exploitation is less clear-cut than it first appears. (Henry H. Em, in Muae, sees “Wings” as an “anti-colonial allegory.”) ↩

-

3

For more on Yi Sang and architecture, see Yoon Jeong Oh, “Yi Sang à Paris: Art of Repetition and Improvisation in 2010 Paris/Seoul,” Journal of Korean and Asian Arts, Vol. 1 (Spring 2020). ↩

-

4

Both sets of poems also contain complex Chinese characters, which were commonly used in Korean works; they would have been “legible, but different” to Japanese readers, according to the translator Sawako Nakayasu. ↩

-

5

Before the signoff is a short phrase (two Chinese characters: 以上), left untranslated by Jung but which Lew renders “As above.” My father translates it as “That’s all,” and notes that in Korean, the characters are pronounced “yi sang”—a homophonic mirroring to mirror the square of reversed numerals. ↩

-

6

In Muae Lew reads this as a homosexual threesome, and locates a strand of queerness running through Yi Sang’s writings, including “Poem No. 15,” which chillingly ends (in Jung’s translation), “It is a great crime to seal up two humans who cannot even shake hands.” ↩

-

7

See Yoon Jeong Oh, “Yi Sang à Paris.” ↩

-

8

Sunyoung Park’s translation of Pak’s book (Asia Publishers, 2015) doesn’t include Yi Sang’s drawings, but they can be seen in Muae. ↩

-

9

It occurs to me now, having read and learned about Yi Sang for many years, that his illness and his profession are not irrelevant to my fascination. My paternal grandmother died of TB the year after Yi Sang did, when my father was only two, and my paternal grandfather worked in the construction business in the 1930s. I dedicate this essay to their memory. ↩