John Banville’s first novel, Nightspawn, published more than fifty years ago, is set in Greece, which was then ruled by a military junta. The Irish protagonist, Benjamin White, is asked, “As a visitor, Benjamin, what do you think of the situation here, I mean the political situation?” He shrugs: “I’m not a political animal.” In The Untouchable, published more than a quarter-century later, the narrator, Victor Maskell, is a version of the English art historian and Soviet spy Sir Anthony Blunt. When Maskell is being recruited by the KGB, he pretends to believe that the artist has “a clear political duty.” He later concludes that his real act of treason was his abandonment of “aesthetic purity in favour of an overtly political stance…. I am guilty of treachery, but in an artistic, not a political, sense.”

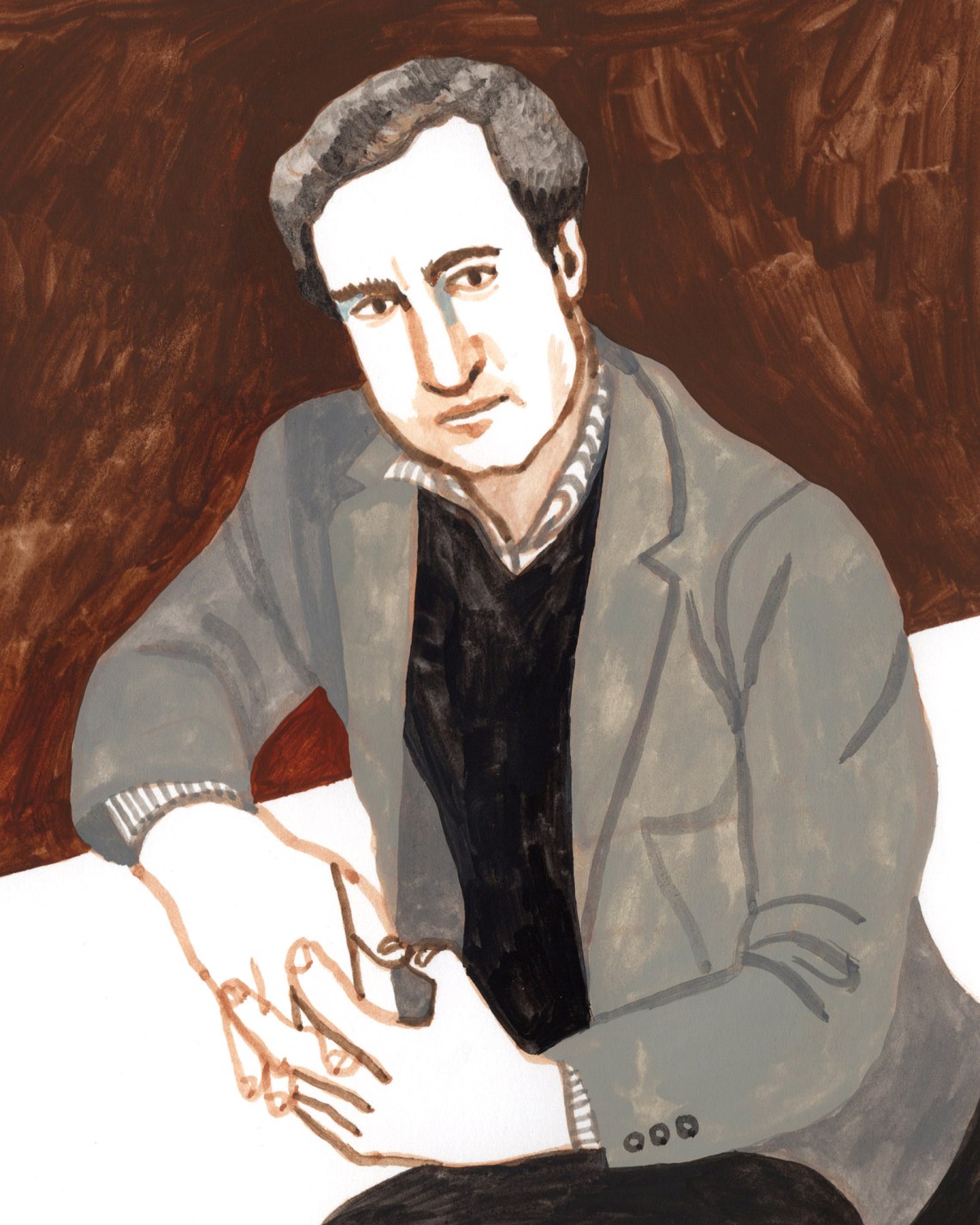

Banville’s own career has been a search for aesthetic purity, a long struggle not to betray the idea of the novel as an object in and for itself. Maskell (like Blunt) is obsessed by the paintings of Nicolas Poussin and insists that their wonder lies in their refusal to mean anything:

The fact is, of course, there is no meaning. Significance, yes; affects; authority; mystery—magic, if you wish—but no meaning. The figures in the Arcadia are not pointing to some fatuous parable about mortality and the soul and salvation; they simply are. Their meaning is that they are there. This is the fundamental fact of artistic creation, the putting in place of something where otherwise there would be nothing.

Banville’s characters are often mesmerized by paintings. The murderer Freddie Montgomery in The Book of Evidence (1989) steals a seventeenth-century Dutch portrait of a woman and lavishes on her the imaginative sympathy he withholds from his victim. In The Blue Guitar (2015) the narrator, Oliver Orme, is a sometime painter, the aim of whose art is, as he puts it, the creation of “autonomous things, things to match the world’s things.” He longs to substitute art for reality, to create on canvas “not the world itself but the world as my mind rendered it.” When he allows too much reality to enter his life, he can no longer paint.

The crisis that overtakes the narrator of Banville’s delicious little masterpiece The Newton Letter (1982) is of a similar nature. He abandons the book he has been writing for years when he loses his “faith in the primacy of text” because “real people keep getting in the way now, objects, landscapes even.” In The Sea, for which Banville won the Booker Prize in 2005, the narrator, Max Morden, is writing (or rather, typically, failing to write) a big book on Pierre Bonnard, and the novel includes a fictional painter named Vaublin, whose name is almost an anagram for “Banville.” In these mocking self-portraits, these satiric alter egos, Banville expresses a desire that is no less potent for being impossible to fulfill: a wish that the novel could aspire to the transcendent condition of certain great paintings, could be only a pattern of exquisite sentences, owing nothing to history, to politics, to reality, even to meaning.

Or, indeed, to that other great encumbrance on aesthetic purity, the matter of Ireland. Banville, from the beginning, revolted against the Irishness of Irish writing, liberating himself not just from the convolutions of its politics but from the descriptive literature that relies on the sense of locality. His debut collection of stories, Long Lankin (1970), is conspicuous for its absences: no childhood memories, no family feuds, no Dublin streets or West of Ireland fields, no Catholic guilt or Protestant decay. The tone is wry, enigmatic—instinct with barely suppressed violence. The novel that made his international reputation in 1981—Kepler, a metafictional account of the seventeenth-century astronomer—is set in Prague, a city Banville had declined to visit, so that too much reality would not intrude on his freedom to invent it.

Banville’s aim was not to convince the reader of the truth of place and character and story, but rather to play with the knowing ways we invest our faith in fictions. “It may not have been like that, any of it,” admits the narrator Gabriel Godkin almost at the end of Birchwood (1973). “The scene of the crime was Geppetto’s toyshop up a narrow lane off Saint Swithin Street,” says Orme in The Blue Guitar, adding, “yes, these names, I know, I’m making them up as I go along.” “Spring came early that year,” declares Gabriel Swan, who tells his story in Mefisto (1986), “no, I’m wrong, it came late.”

Banville’s auto-chroniclers are usually, like their creator, pure fabulists. They are anti-historians. Irish history, when it does encroach on these novels, is just another grotesque fable. Birchwood is a brilliant burlesque of the Irish Big House novel, that peculiar genre set in the grand (though usually decaying) mansions of the Protestant landlord class. It turns even the most somber episode of Irish history—the Great Famine of the 1840s—into an extravaganza of awfulness so terrible that it topples over into grotesque humor:

Advertisement

Bands of savage-fanged hermaphrodites stalked the countryside at night killing and looting. Some said they ate their victims. These preposterous stories made us laugh…. We played with exaggeration as a means of keeping reality at bay.

So, for most of his career, did Banville.

And then came Benjamin Black, by name the opposite of the Benjamin White of Nightspawn. Banville invented the pseudonym Black in 2004, ironically just before his image as a votary of aesthetic purity received the endorsement of the Booker Prize. Black debuted with a thriller, Christine Falls, set in 1950s Dublin, the first of a continuing series featuring a dour, middle-aged alcoholic pathologist, Quirke (his first name is never mentioned). For a long time, Black was someone else: as his creator told The Guardian in 2014, he and Banville “are two completely different writers who have two completely different processes.”

But in 2020, when he published Snow, a thriller populated by some of the recurring figures from the Quirke novels, an even stranger thing happened: Black’s name on the cover was replaced by Banville’s own. With that novel, and then with the recent April in Spain, the “two completely different writers” agreed on a merger. Those opposites—the upholder of aesthetic purity and the purveyor of engrossing crime stories—have become, if not quite one and the same, then two sides of the same artistic persona. What has happened in this process is fascinating: Irish reality, which Banville kept at bay for so long and with such relentless energy of creation, has flooded through the dikes. Politics, history, place, and time will not be denied after all.

The divide between cerebral fable and thriller was never, in Banville’s work or in that of the writers who preceded him, absolute. Jorge Luis Borges played with the detective story. Franz Kafka’s The Trial and Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita are, in their own ways, crime novels. The second half of Samuel Beckett’s Molloy is narrated by a private eye, Moran. (“What was his name?” wonders one character about another in April in Spain, “Murphy? Molloy? Moran? He couldn’t remember.”) The protagonists of Banville’s non–Benjamin Black novels are often criminals: Maskell a traitor, Montgomery a murderer, Orme a kleptomaniac. All are, in some sense, also detectives seeking to unlock the mysteries of their own selves. The writer in The Newton Letter thinks of the scraps of memory that come to him as “at once commonplace and unique, like clues at the scene of a crime.”

Conversely, the Black/Banville thrillers don’t leave metafiction completely behind. “They always ended in gunplay, these plots, with bodies, much too neat and unrumpled, all over the place,” we read in the second of the Quirke novels, The Silver Swan (2008). The first full chapter of Snow begins with the almost parodic words “The body is in the library,” and the skeptical daughter of the house asks Strafford, the detective who has arrived to investigate, “Will you be calling us all together at dinnertime to explain the plot and reveal the killer’s name?” Strafford is well aware that the Agatha Christie mystery in which he finds himself is a thin cover for the absurd: “There was always the danger, in his job, of seeing things that weren’t there, of making a pattern where there wasn’t one. The policeman insists that there be a plot. However, life itself is plotless.”

Most importantly, the crime novels have their share of Banville’s distinctive inventiveness, his magical ability to forge similes that are at once startling and apt. In The Untouchable, for example, “Sodden sycamore leaves lolloped about the road like injured toads.” In The Sea, waves break on the shore “like a hem being turned endlessly by a sleepy seamstress.” In The Blue Guitar, the vapor rising from a teapot is “like a half-hearted genie trying and failing to materialise.” Raindrops fall on the road “like a corps of tiny ballet dancers.” This inability to stop considering how “everything is always like something else” is what Orme in that novel refers to as “this shiftingness I see in all things.”

The shiftingness of things recurs in the thrillers, like Banville’s artistic fingerprints left at the scene of the crime. Especially in the two most recent books, the voltage of the imagery is just as high as it is in the literary novels. In April in Spain, a prim character makes love “like a doctor searching for the source of an obscure malady.” In Snow, the molten wax spilled over the side of a candlestick is “like a frozen cascade of champagne.” The toe caps of a man’s highly polished brown shoes “gleamed in the firelight like chestnuts fresh out of their husks.” For the detective Strafford, as for Banville’s earlier narrators, “the dullest object could…flare into sudden significance, could throb in the sudden awareness of itself.” The policeman and the novelist share this wildly associative habit of mind in which everything is also something else, the ordinary perpetually on the brink of becoming numinous, the real tipping over into the surreal.

Advertisement

Yet these crime novels are also very different from Banville’s earlier work. They move more quickly. There is less pressure on the sentences. The solipsistic unreliable narrators are replaced by the cool omniscience of the invisible but authoritative author. Plot, however cleverly it is acknowledged to follow a set of well-known conventions, matters much more. Above all, the murder mystery posits at least one irreducible reality that must be accepted by both the characters and the reader: the dead body. Life may be plotless, but as Strafford has to remind himself in Snow, “a man had been murdered, and someone had murdered him. That much had happened.” The thriller must admit the actual. The mystery of things must be at least momentarily soluble.

It is telling that the dominant figure in these stories, Quirke, is a pathologist, first introduced in Christine Falls as a familiar of corpses: “It was not the dead that seemed to Quirke uncanny but the living.” For Banville’s thrillers are an autopsy on a dead society. Laid out on his dissecting table is Holy Catholic Ireland, a body politic very much alive for most of Banville’s life but now definitively deceased. The cause of death, as it’s traced in these stories, is a cruel incestuousness, both metaphorical and literal. In this anatomy of the Republic of Ireland in the 1950s, Church and State are in bed together, locked in illicit embrace. Physical incest itself is a recurrent driver of the plots. April in Spain and the novel to which it is a sequel, Elegy for April (2010), cut deep into a powerful political family, the Latimers, whose patriarch has abused his son before moving on to the title character, his daughter. And institutionalized terrorization of women and children weighs heavily on these novels. Banville, in opening up the matter of Ireland, has let in some very dark matter indeed.

Strafford reminds himself that “that much had happened,” and the same can be said of the real events that frame these plots. In both Christine Falls and Even the Dead (2015), Quirke and his collaborator, Inspector Hackett, trace killings back to a Catholic network that is selling to rich Americans, with the collusion of state authorities, babies born out of wedlock in Church-controlled institutions. The killings may be fictional, but there really was a large-scale trade in Irish babies (attractive to prospective American adoptive parents because they were white) run by Catholic organizations and silently supported by the government. It briefly became an international story in 1951 when the Hollywood star Jane Russell announced her intention “to fly to Dublin…to pick out a child.” But this did nothing to stop the practice, which continued for another twenty years.

Thrillers invariably unfold in a universe governed by hidden forces, where authority is corrupt and connected people conspire to suppress truths and make inquisitive individuals disappear. In this sense, the thriller is Platonic: there are mere appearances, but behind them are the eternal forms of pure power. Banville’s crime stories revel in this doubleness. In A Death in Summer (2011), a recurring character, Costigan, the fixer for a sinister Catholic outfit called the Knights of Saint Patrick, warns Quirke:

There are two distinct worlds, the world where everything seems grand and straightforward and simple—that’s the world that the majority of people live in, or at least imagine they live in—and then there’s the real world, where the real things go on.

In this crooked theocracy, the transcendent is just another form of thuggery.

What is most striking, however, is how little of this Banville needs to invent. There are, certainly, the usual exaggerations of the genre. In April in Spain, a government minister gets the most senior civil servant to hire a hit man to do away with the overly curious Quirke. Such things did not happen. But the system of watchfulness and control that Banville evokes so well, with its ability to make awkward facts vanish into obscurity—and awkward women and children vanish into hellish institutions—is no exaggeration. Hovering over everything in these novels is a figure who is given his real name, John Charles McQuaid, the Catholic archbishop of Dublin, who was one of the most powerful figures in the country between the 1930s and his retirement in 1972.

McQuaid most certainly existed—I once served as an altar boy for a solemn requiem Latin Mass he performed, and it was like being a peasant in the presence of a medieval monarch. He has been much written about by historians, but in Snow Banville, through a mesmerizing feat of imaginative necromancy, conjures him from the dead in all the understated glory of his unquestionable power. Because Strafford is investigating the murder of a priest, he is summoned by McQuaid. The encounter is superbly handled. Banville captures the way real authority is projected not by overt bullying but through a quiet assumption of obedience. McQuaid does not issue instructions to Strafford to cover up the true circumstances of the crime. He speaks softly:

The duty falls to some of us to calculate what is best for the congregation—forgive me, for the population, at large. As Mr. Eliot says—I’m sure you’re acquainted with his work?—“humankind cannot bear very much reality.” The social contract is a fragile document. Do you take my point, at all?

McQuaid is thus a character from an old Banville novel, trying to keep reality at bay.

The truth that must not be uttered is that the murdered priest, Father Tom Lawless, was not merely stabbed but castrated. Understanding why someone would have been driven to do that would open a door into the Church-run system of so-called industrial schools, where children whose parents could not care for them or who were deemed delinquent were incarcerated under the control of religious orders, notably the Christian Brothers. Father Tom, we learn, had been chaplain to one of those schools, which Banville calls Carricklea.

Here Banville achieves something that could only be done in fiction—telling the story of what went on in such places from the point of view of an unrepentant abuser. Without warning, Snow shifts back ten years to an interlude written in the voice of the now dead priest. Father Tom becomes one of Banville’s solipsistic first-person narrators, stylistically a version of Maskell or Orme or Montgomery. But the story he spins is no fable. It is a proud retailing of his systematic crimes against a boy. That boy is now a young man who works on the estate where the priest has been murdered. There is no great mystery about the connection between them and its place in the plot. What is remarkable, rather, is the way this passage takes us into the heart of a darkness that these thrillers have long been circling. Carricklea looms over the whole sequence of Quirke stories. Collectively, they form a kind of Big House novel, but the Big House in question is this nightmarish edifice where the Church’s absolute power was exercised in the physical and sexual abuse of defenseless children.

Carricklea is not an invention. Most Irish readers would recognize it as Letterfrack, the most notorious of the industrial schools, situated in the remote west of Ireland. Even as a child in Dublin, I knew that name. It was the place you could be sent if you were not good. It could not have functioned as such a warning if it were not known, at some level, to be a house of horrors. But this was never stated or specified. What went on there—a perpetual open season on the minds and bodies of children—was not fully acknowledged by the Irish state until well into this century. Arguably it has not yet been fully accepted imaginatively, in the sense of being absorbed into the general consciousness of contemporary Irish culture. Banville, whether or not he fully knew it at the beginning of his second life as a thriller writer, invented Benjamin Black—and Black invented Quirke—in order finally to be able to do precisely this.

The real twist in the Quirke books is not the whodunit revelations at the end. Carricklea is not an undiscovered country that the pathologist will be forced to enter if he is to understand the crimes he is investigating. It is already there, inside his head. For we learn early on, fifty pages into Christine Falls, that Quirke himself spent his early childhood in industrial schools, most of it in Carricklea. At first, this is peripheral biographical detail. But over the course of the novels, Carricklea pushes its way more and more insistently into the center.

Banville is writing, through Quirke, the kind of history that is the novelist’s proper concern—the history of a trauma that’s fully contained within the character he has invented. “As a child,” we are told in Holy Orders (2013), “Quirke had been abused, body and soul, by priests and brothers, at Carricklea, and other places before that.” It is not explicitly stated in the novels that this included sexual abuse, but it does not have to be. In A Death in Summer, Quirke visits an orphanage where the boys are being subjected to the depredations of a ring of well-connected pedophiles, and is struck by recognition:

He recalled too the boys sidling past in the corridors, their downcast eyes. How could he have missed what was plain to see, what his own experiences as a child in places like this should have taught him never to forget?

Where Banville’s artistry most reveals itself is in the reversal of his usual exuberance of association. Both for his characters and in the imagery of his novels, “everything is always like something else.” But for Quirke, and Quirke alone, everything is always like Carricklea. Morden in The Sea says, “The past beats inside me like a second heart,” and Quirke could say the same. He harbors “another version of him, a personality within a personality, malcontent, vindictive, ever ready to provoke, to which he gave the name ‘Carricklea.’” This second self can be awoken by anything and everything. In April in Spain, he becomes agitated when his wife is knitting:

“There was an old Christian Brother, in the place where I was,” Quirke said—he never spoke the name of Carricklea if he could avoid it. “His dentures were loose.”

“Oh, yes?”

“They used to make a sound just like that, just like you knitting.” The needles went still. She looked at him. He turned his eyes away from hers.

He is, in Holy Orders, even afraid of raindrops, because the odor of wet woolen clothing brings to mind “the smell of sheep his clothes gave off, which always reminded him of being at Sunday evening devotions in the chapel at Carricklea.” Merely descending the stairs at the hospital where he works ignites flashbacks:

He went down the big curving marble staircase, and as he did so he had, as always, the panicky yet not entirely unpleasant sensation of slowly submerging into some dim, soft, intangible element. He thought again of being a child at Carricklea and how when he was having his weekly bath and if there was no Christian Brother around to stop him he would let himself slide underneath the water until he was entirely submerged.

Clocks, dusty documents, woodchips, pencil shavings—there is nothing that cannot suck Quirke back into the secret history Ireland hid from itself for so long. He is, wherever he happens to be, always at a crime scene in which the most innocent objects are radioactive with the memory of violence and terror. The crime scene is the entire country. These thrillers have become not just an autopsy but an inquest into the abuse of the untrammeled power the country gave to the Church. It seems quite right that one of Ireland’s best writers has now given his own name to it. On the title pages of these books, Banville is saying, as Ireland as a whole must say: This thing of darkness I acknowledge mine.

This Issue

February 24, 2022

Liberation Psychology

‘Invitations to Dig Deeper’

Riffraff