The Ukraine war and global economic troubles momentarily overshadowed domestic discord in the United States earlier this year, but it didn’t go away. The groundless insistence by former president Donald Trump and his supporters that the 2020 election was stolen, Republican efforts to limit voting rights and to install state officials willing to disregard adverse election results, and the activity of far-right militias that orchestrated the insurrection in Washington on January 6, 2021, have all continued. Trump is bent on vengeance, and he intends a sweeping replacement of federal civil servants with loyalists if he is reelected president in 2024.1

In June the Supreme Court handed down a series of grossly retrogressive decisions on guns, abortion, and environmental regulation that have threatened America with fragmentation to a degree not seen since the Civil War.2 The midterm elections in November may well make political conflict more likely. If, as could happen, control of the House and Senate flips to the Republican Party, legislative gridlock in Congress is practically guaranteed, as is a slew of partisan congressional investigations into President Joe Biden and his administration. These could lead to his impeachment despite the absence of any plausible “high crimes and misdemeanors.” Democrats will be outraged, while Senate Republicans will be unlikely to have the votes to convict him.

Several commentators have suggested that, historically, radical swings in domestic politics and virulent strains of racism and fascism have in fact been normal in the United States, and that talk of prospective large-scale political violence is therefore overblown. But the breadth and depth of the present threat to the country seems unprecedented in post–Civil War America.3 Among other things, the conflation of Christianity and Republican politics fostered by political elites and powerfully felt at the grassroots level is encouraging absolutism on the right. Political rallies for Republican candidates and causes, especially those anticipating Trump’s second coming, are increasingly infused with religious language and symbols, and feel akin to evangelical revival meetings.4 Studies of militant Islamist movements have highlighted the dangers inherent in sacralizing political grievances. Once secular policies are interpreted by their opponents as impious challenges to God’s rule, compromise becomes apostasy.

Emancipation of the enslaved in 1863, the defeat of the Confederate states in 1865, and postwar Reconstruction did not prevent the reestablishment of an informal confederacy. The imperative of reincorporating the South into the Union led northern elites to tolerate and eventually internalize the gauzy southern myth of the Lost Cause: a gracious agrarian culture, guided by an honor code and a noble aristocracy, that was defeated by a soulless industrial society. Contemporary Republicans have refashioned that myth into one of a predominantly white, Christian America that other races and cultures have compromised and that is bound to perish unless prompt and decisive action is taken; that is the fundamental if unspoken meaning of Trump’s “Make America Great Again.”

The US now appears to be in a state of “unstable equilibrium”—a term originating in physics to describe a body whose slight displacement will cause other forces to move it even further away from its original position. Political analysts have applied the term to countries on the brink of civil war, like Lebanon and Syria. But could the US really descend into political violence and perhaps even civil war, as commentators such as Stephen Marche and, less breathlessly and more systematically, Barbara F. Walter have suggested?5

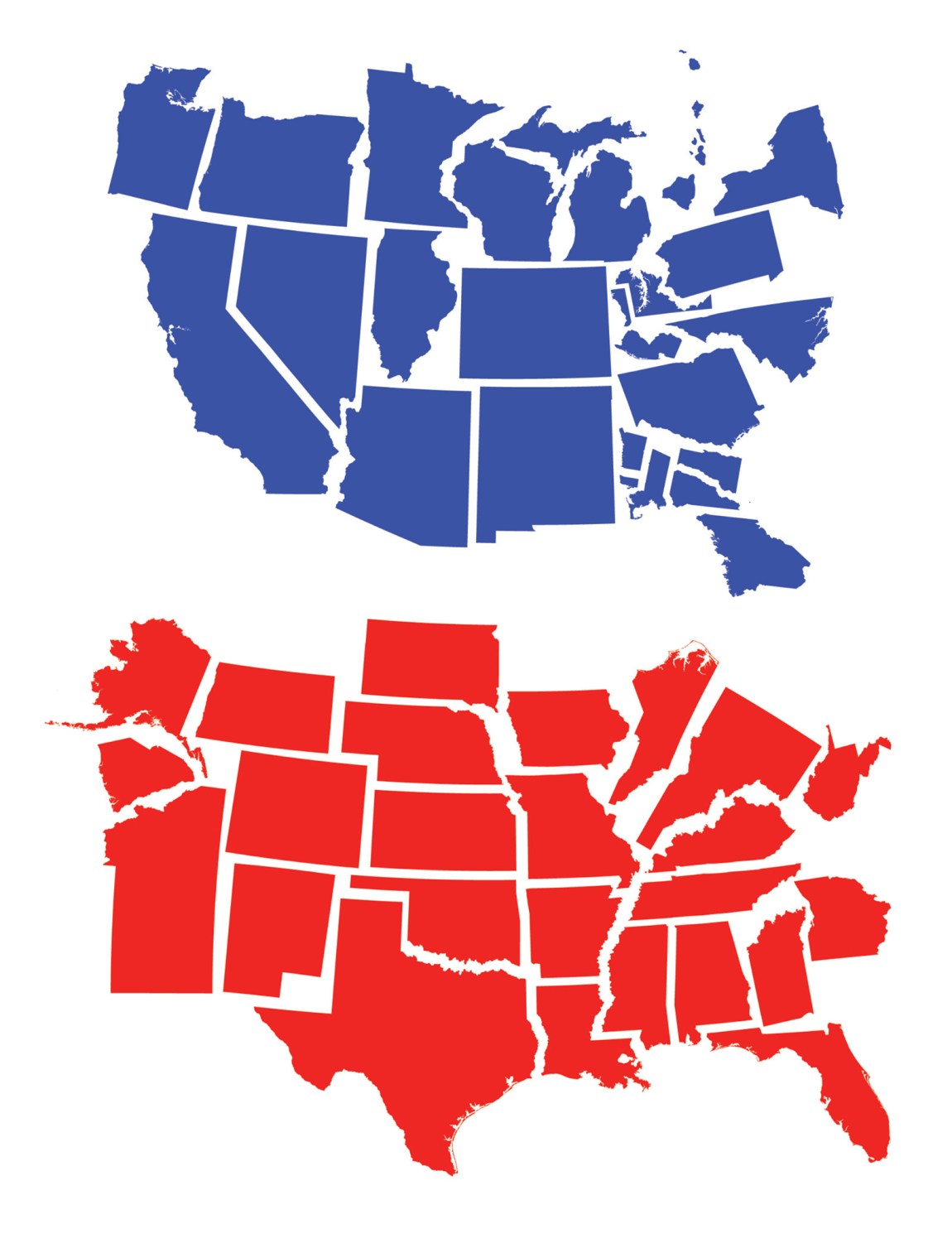

America is already virtually a binational state, with two sharply opposed national communities comparable in size and political strength that effectively operate as confederations under a single federal government. The Republican Party is mostly white and marginally increasing its Latino membership, the Democratic Party an ethnic and racial mix. Although Democrats occasionally reveal impulses toward reconciliation, Republicans largely do not. Most have put up implacable resistance to Biden’s efforts to bolster the middle class and combat climate change, and, reaching back at least a decade, to Democratic nominations of eminently qualified federal district and appeals court judges as well as Supreme Court justices.

At the core of the US binational character is a deep and durable tension between a Christian white-supremacist ideology that evolved to justify slavery and a broad-based multiethnic resistance to it. Reinforcing this tension are cultural divisions between the rural and urban populations, including divergent values on education and immigration. The splits between the two halves of the nation—red and blue, right and left—increasingly appear irreconcilable. Today, new state legislation on abortion, LGBTQ rights, gun rights, free speech, and public health is making red and blue states radically different.6 Many Americans have relegated their political adversaries to the category of “the other,” an ominous prelude to the dehumanization that facilitates violence in civil conflict.

The language used by the two sides to describe each other reflects a mutual loathing. Trump’s base harbors an imaginary view of blue states as submerged in a vortex of violence, crushing poverty, and ghastly cults presided over by Communists, antifascist (“antifa”) militants, and child abusers. In his speech in July at the America First Agenda Summit in Washington—widely seen as a soft launch of his campaign for the presidency in 2024—the former president amped up the “American carnage” theme he first articulated in his 2017 inaugural address. Trump called the US a “cesspool of crime” and American cities “war zones” stalked by “drugged-out lunatic[s]”; he praised Chinese president Xi Jinping’s quick trials and executions of drug dealers and indicated that he too would rule like a dictator, enabled by a compliant Congress. While violent crime has increased only marginally and sporadically and rural mayhem is outpacing urban crime, his rhetoric was plainly exclusionary, reminiscent of the post–Civil War demonization of African Americans.

Advertisement

Democrats oppose a host of intransigent Republican positions. They believe, correctly, that Republicans have entrenched a kind of minority rule, primarily through their deftly obstructionist use of Senate rules and procedures, and more broadly through gerrymandering, voter suppression, and the manipulation of the judicial appointment process. A majority of Republicans say they believe that the 2020 presidential election was fraudulent, and they are likely to consider future Democratic victories similarly bogus and therefore subject to challenge, potentially with force.7 Each party thinks that the other poses a mortal threat to the future of the country. The fear is especially acute among a large percentage of Republicans and white Americans who see themselves in a Manichaean struggle against nonwhites, illegal aliens, secularists, purveyors of critical race theory, a mendacious liberal media, and a cabal of treasonous elites and socialists bent on destroying the “real” America.

Right-wing political violence has become more prevalent, from the Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, in August 2017 to vigilante actions against largely nonviolent Black Lives Matter demonstrations and the January 6 insurrection. According to a survey last fall by the Public Religion Research Institute, some 30 percent of Republicans today believe that “true American patriots may have to resort to violence in order to save our country.” Republican elected officials have made explicit threats of violence in response to alleged election fraud and to vaccine and mask mandates.8 Last year Representative Paul Gosar, a Republican from Arizona, tweeted a cartoon of himself murdering progressive Democratic representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez of New York and menacing Biden with swords. The House voted to censure him, but just barely and along party lines.

It is little consolation that such behavior is not unique in American politics: the brawls and duels that were frequent in Congress between 1830 and 1860 were often over disagreements that led to the Civil War.9 And Trump’s popularity has waned only marginally despite evidence presented by the House Select Committee that he incited an insurrection by a broad-based group of armed insurgents and refused to call them off even when it appeared that they intended to murder the vice-president to prevent an orderly transition of power.

A far-right effort is underway to introduce violent intimidation into conventional politics, not unlike the fascist campaign to undermine the Weimar Republic a century ago. According to the FBI, most domestic terrorist attacks are carried out by antigovernment and white supremacist militants on the right. Their leaders may judge their target rather soft. The unpreparedness of the authorities as the January 6 insurrection unfolded can only encourage them. But even under Biden, federal agencies have hesitated to undertake major enforcement action against militias for fear of situations like those that occurred at Waco and Ruby Ridge in the early 1990s; they now appear afraid that one stray bullet could ignite escalating violence. Similar thinking may inform Attorney General Merrick Garland’s apparent reluctance to indict Trump and those in his inner circle over January 6. The incitements and threats of violence provoked by the FBI’s recent execution of a search warrant at Mar-a-Lago, Trump’s Florida residence, are liable to reinforce these worries. Local elected law enforcement officials in Republican-controlled jurisdictions, for their part, are inclined to refrain from prosecuting those in their increasingly radicalized “base.”

In light of federal timidity and state and local support, what National Defense University professor David Ucko has called “infiltrative insurgency” appears to be a crucial element of the right’s strategy for 2024: militia members leave their guns in their trucks, run as Republicans in local and state elections, and discreetly serve on congressional staffs.10 As elected officials, even if pending federal legislation curtails their ability to manipulate the tally of electoral votes, they will be better able to push for more zealous policing of the voting process and to deny the certification of ballots on a countywide basis, which could disrupt national elections.11

Advertisement

Meanwhile, Republican activists are working to enlist local law enforcement officials—many of whom are already sympathetic to militias and a few of whom are members—to carry out such stratagems.12 In extreme cases, a strong local insurgency could infiltrate state government sufficiently to at least de facto withdraw it from federal control. The radical Republican factions and militia movements in Idaho and parts of Northern California are angling in this direction.13 Guiding their effort is the book Confrontational Politics (2009) by the former California state senator and gun rights fundamentalist H.L. Richardson, which is becoming as important to the far-right cause as The Turner Diaries and tracts on “replacement theory.”

A poll in July and August 2021 indicated that many Republicans and a large plurality of Democrats support a formal separation of red or blue states. Other polls have yielded similar results.14 In June the Texas Republican Party approved platform planks declaring Biden’s 2020 election victory illegitimate and calling for a vote “for the people of Texas to determine whether or not the State of Texas should reassert its status as an independent nation.”

Regardless of who wins, the 2024 presidential election could be a turning point in American politics. One party could emerge with control of both the executive and the legislative branches of the federal government. If the Republicans are in this position, they will undoubtedly seek to further skew the electoral process in their favor and to criminalize political activities such as peaceful mass demonstrations, reducing Democrats’ ability to resist nonviolently. Democrats’ tendency to play by the rules and their disdain for organized violence would probably delay civil conflict. But a Republican president would likely deploy federal agencies to suppress nonviolent demonstrations, as Trump did in 2020.15 Intolerance and violence would increase, incrementally and then exponentially.

Alternatively, and perhaps most likely, one party might gain decisive control of the legislative branch while control of the executive branch was contested. In this situation, the Supreme Court would become critical in deciding which of two claimants to the presidency, both with strong popular support, would occupy the White House. Given its pronounced rightward tilt and virtually inevitable Republican threats of open rebellion with an eye to a “successful” January 6, the Court would probably favor the Republican claimant. Assuming Democrats controlled Congress, the immediate effect would be political and governmental paralysis at the federal level. Governance would gradually devolve to the state level. If Republicans controlled Congress, the process of devolution would presumably be faster. 16

The lives and business activities of Americans are mostly regulated by state laws. States and localities have their own judicial systems, law enforcement and public safety agencies, educational systems, social services, and health care systems. Nevertheless, individual states would probably see significant advantages to joining with others that share their political leanings. If this led to secession, it would cause greater geographic and demographic trauma than the secession of the southern states did in the 1860s because American political geography is much more variegated now. Noncontiguous southern and western interior red states and even more distantly separated northern and far-western blue states would be angling for separation.

Large numbers of inhabitants of a prospective blue nation might well want to live in a red one, and vice versa. For example, there are clusters of Democratic voters in the South and lower Texas, and clusters of Republican voters in California and some mid-Atlantic and New England states. Thus, there would likely be substantial internal migration and displacement before, during, and after the creation of the new entities, while many others made their peace with the new dispensation and stayed put.17

Not everyone, of course, would abandon their homes quietly. In the early stages of a civil conflict, political demands and preferences would likely be evolving and fluid. Some participants would favor simply taking control of the national government and suppressing dissent. Citizens of individual states might tentatively advocate de facto secession, expecting accommodation from the federal government. If those of other states followed suit and secessionists coalesced into one or more multistate blocs, de jure secession could gain momentum. Internecine unrest—including street violence, assassinations of prominent figures, kidnappings and bombings—might arise and insidiously intensify.

In the grip of a full-blown crisis, local, state, and even federal law enforcement—and courts—could become susceptible to sectarian impulses and allow violence to escalate to the point of forced population displacement. This is how political disarray becomes civil war. There was Bloody Kansas before there was Fort Sumter. Were matters to reach that point, war would become “a self-righteous fact, no questions asked.”18 Tribalism would harden the combatants’ commitment, and their sacrifice would perpetuate it.

Even if a civil war devolved to a relatively small number of true believers fighting on with little outside support, they could still wreak havoc, as the Provisional Irish Republican Army did for twenty-five years and armed militias like the Ku Klux Klan did in the Deep South following the Civil War, making it difficult to bring the war to an end in the absence of tacit political concessions. One such concession after the Civil War was acquiescence to the Black Codes and subsequently Jim Crow, which left the country ideologically bedeviled and potentially unstable, and a large segment of the population victimized and humiliated. History might not repeat itself, but it could ominously rhyme. Such dismal prospects are reasons to anticipate civil war and secession and to devise realistic, if inevitably painful, measures for forestalling them.

It is tempting to respond that there is time to reunite the United States and reasonable hope for doing so. There seems to be a broad political middle that can restore national political equilibrium. Despite the emerging divisions, an increasing number of Americans now reject both main political parties. A recent Gallup poll indicates that 28 percent are registered as Republicans, 29 percent as Democrats, and 41 percent as independents. Optimists observe that there is a “representation gap”—that is, the parties are more extreme than most voters—which suggests that a silent moderate majority can be counted on to keep the country politically stable. Yet independent voters tend to have low interest in and knowledge of politics and to include some holding an idiosyncratic mix of extreme views.

Thus, given today’s populism-stoked politics, moderates on both sides may come to see their own party’s program as indivisible and be prepared to take the bad with the good. The reciprocal demonization of the two parties reflects and drives this dynamic. Future cross-party coalitions may become impossible to imagine, let alone construct.

The trend toward expansive gun rights and a broad legal definition of self-defense, facilitated by state-level “stand your ground” and citizen’s-arrest statutes, are bound to increase vigilantism and right-wing militia recruitment. Vivid and disturbing illustrations include Kyle Rittenhouse’s acquittal in Wisconsin last November for shooting a left-wing protester dead and his subsequent valorization by the far right. Especially concerning is the distillation of extreme right-wing views into the platforms of state Republican parties, as has occurred in Texas. This indicates that extremism is being normalized in mainstream right-of-center politics and entrenched through an infiltrative insurgency, and hence will be more difficult to purge or circumvent.

Before civil strife acquires critical momentum, Democrats need to embrace a more radical political solution to stave it off. Purposeful defederalization is one possibility. There is a case to be made that the raison d’être for federalism has passed. The primary reasons for a strong federal government in 1789, after the Revolutionary War, was the lingering threat from Great Britain and the hunger for more territory, which required national power to acquire. Other comparable threats—from Wilhelmine Germany, Nazi Germany, imperial Japan, and the Soviet Union—have come and gone, and there is no more land to take.

When the federal system works democratically, it delivers median results. There are winners and losers, but the broad middle is satisfied. Under such federalism, if Congress were to take up abortion rights, for example, some states would want to ban the procedure entirely and others to allow it far into the term of pregnancy. A bill that ultimately reaches the president’s desk for signature might ban it after twelve weeks or twenty-four. In the current political environment, such a broad national acceptance of compromise is improbable. Biden’s insistence on bipartisanship and moderation, and faith in a return to political business as usual, admirable though they are, therefore seem unrealistic.

Of course, if this were the only problem, the benefits of federalization might still outweigh its costs. But an effective Republican supermajority in Congress reinforced by an antidemocratic president, a federal government consisting entirely of personnel selected for their kindred views and loyalty, and the current far-right Supreme Court would displace the normal democratic politics of median results with something more sinister and coercive: populist authoritarianism. This, we stress, is a plausible forecast, not an outright prediction. But the stakes and probabilities are so high that it is only prudent to consider formalizing a defederalization arrangement to preempt that grim prospect.

Defederalization might begin with the devolution of federal authority over many areas to states. Such an approach would be implemented in an ad hoc, uncoordinated way within existing political institutions. This is already happening with respect to gun-carry laws, abortion access, and federal funding for religious schools, and Supreme Court decisions make it possible.

An improvised system, however, would leave many Americans unprotected and perpetuate potentially violent disputes. In a more deliberate, orderly process, there are two broad structural possibilities. One would be a partial defederalization, in which a national legislature would pass laws relating to the funding and maintenance of the armed forces and other national assets, mainly infrastructure, and otherwise leave the states to govern themselves. This would bear a passing resemblance to the EU. The other would entail complete separation into two successor states, each of which would federate internally to the degree necessary.

Achieving this kind of defederalization would not be easy. Polls suggest that most Democrats continue to value America’s economic and strategic power as a strong, centralized state, as well its capacity to protect the rights of marginalized and historically abused classes of people in potentially hostile states. But from an economic standpoint, blue states might welcome more systemic separation from red states. Because red states benefit more from the federal distribution of tax dollars, it would be to their advantage to maintain the status quo and retain the essentially parasitic economic arrangement and minority rule that have served them well, while building a repressive apparatus to tamp down dissent.19

Presumably defederalization would require the consent of all fifty states via referendums. This process would be complicated, with “leave” and “stay” groups in each state working aggressively to shape the voters’ views. Such radical changes in the structure of the federal government would require multiple constitutional amendments and, practically speaking, a constitutional convention.

Beyond the conscience of the left and the antidemocratic tendencies of the right, the organizational challenges to defederalization are daunting. A major one is that of continental defense and the need for armed forces capable of securing the borders and a broader security perimeter. A crucial subsidiary question is how the US military establishment would react to the sharpened political divisions that defederalization would imply.

There is significant support for right-wing extremism among serving and retired military members, as indicated by their disproportionate influence in right-wing militias.20 The odd senior officer—former three-star general Michael Flynn is an egregious example—might also lean in that direction.21 If the military leadership were to decisively split along political lines such that each side had its own headquarters, recruitment system, staff, and force structure, then questions would arise as to who gets which assets and what they would do with them. It is conceivable, for example, that a red faction would control a powerful and expensive force—commandeering military bases, weapons, armored assets, or other hardware, most of which are located in red states—while a blue faction might field a relatively weak rump contingent.

The military, however, is a highly professionalized organization. Senior officers generally resisted Trump’s attempts to manipulate it into undertaking extraconstitutional duties, such as suppressing domestic political protest. So it seems likely that the military leadership would spurn partisan attempts at co-optation by rogue officers, militias, or state-level armed forces upon defederalization. In that case, and if the two political blocs could agree on a budget, including pensions and disability benefits, and a formula for allocating it, as well as ways of serving red and blue security interests equitably, national security would be manageable. The military would remain institutionally unified and apolitical, although constrained by the increased difficulty of forging national consensus about projecting American power or participating in overseas military conflicts. Another vexing question is who would inherit US treaty obligations and how they would serve them.

Domestic conundrums would abound. Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid would need to be sustained by states that want to preserve them. Decisions would be required about currency and monetary policy and the nature of the federal reserve system. The energy transmission grid, communications networks, pipelines, and transportation infrastructure straddle red and blue states. Political migrants might be quite numerous and would need to be resettled at substantial cost. Some states—Maine, for example—are divided geographically between a relatively liberal blue coast and a red interior. Would such states split? Would coastal Maine join Massachusetts in an ironic comment on the Missouri Compromise, which split the state from Massachusetts to balance Missouri’s entry into the Union as a slave state? To be workable, any revision of interior borders would have to build in prohibitions against attempts to revert to original borders. The dilemmas of Brexit were comparatively straightforward and still, six years on, have not been sorted out. But the knottiness of the problem is no reason to avoid it; it is the reason to confront it.

The reality is that the states are no longer united—if, other than during the world wars and the cold war, they ever really were. The sooner some process of matching political form to political substance gets underway, the less likely the transition is to be violent. Many Americans—conservative as well as liberal—would see defederalization as tantamount to an admission that the US can no longer boast of an enlightened and ideologically cohesive citizenry, and is no longer a large and powerful unitary democracy, a political exemplar to the world, and a potential global force for good. Sadly, it may come to that.

—August 24, 2022

-

1

See Jonathan Swan, “A Radical Plan for Trump’s Second Term,” Axios, July 22, 2022; and “Trump’s Revenge,” Axios, July 23, 2022. ↩

-

2

See our “We Need to Think the Unthinkable About Our Country,” The New York Times, January 13, 2022. ↩

-

3

See Nikhil Pal Singh, “America’s Crisis-Industrial Complex,” New Statesman, June 2022. ↩

-

4

See Elizabeth Dias and Ruth Graham, “The Growing Religious Fervor in the American Right: ‘This Is a Jesus Movement,’” The New York Times, April 6, 2022. ↩

-

5

See Stephen Marche, The Next Civil War: Dispatches from the American Future (Avid Reader, 2022); and Barbara F. Walter, How Civil Wars Start: And How to Stop Them (Crown, 2022). ↩

-

6

See Shawn Hubler and Jill Cowan, “Flurry of New Laws Move Blue and Red States Further Apart,” The New York Times, April 3, 2022. ↩

-

7

Recent polling on this question indicates that 58 percent of Republicans believe that Biden stole the election, and just 37 percent are confident the next presidential election will be open and fair. See Mallory Newall, James Diamond, and Neil Lloyd, “Election Fairness, Confidence in Democracy Remain a Partisan Issue,” Ipsos, November 20, 2021. ↩

-

8

See Lisa Lerer and Astead W. Herndon, “Menace Enters the Republican Mainstream,” The New York Times, November 12, 2021. ↩

-

9

See Joanne B. Freeman, The Field of Blood: Violence in Congress and the Road to Civil War (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2018). ↩

-

10

See David H. Ucko, The Insurgent’s Dilemma: A Struggle to Prevail (Oxford University Press, 2022). ↩

-

11

See Blake Hounshell and Nick Corasaniti, “A Hidden New Threat to US Elections,” The New York Times, July 22, 2022. ↩

-

12

See Alexandra Berzon and Nick Corasaniti, “2020 Election Deniers Seek Out Powerful Allies: County Sheriffs,” The New York Times, July 25, 2022. ↩

-

13

See Christopher Mathias, “Living with the Far-Right Insurgency in Idaho,” HuffPost, May 17, 2022. ↩

-

14

See “New Initiative Explores Deep, Persistent Divides Between Biden and Trump Voters,” University of Virginia Center for Politics, September 30, 2021; and Adam Barnes, “Shocking Poll Finds Many Americans Now Want to Secede from the United States,” The Hill, July 15, 2021. ↩

-

15

See Jonathan Stevenson, “Trump’s Praetorian Guard,” The New York Review, October 22, 2020. ↩

-

16

A third scenario, in which Democrats decisively gain national power, the right rejects their authority, and the Democratic national government resists, is arguably playing out right now. See Barton Gellman, “January 6 Was Practice,” The Atlantic, January–February 2022. ↩

-

17

For a fluent discussion of comparative cases, see Max Hastings, “An American Secession? It’s Not That Far-fetched,” Bloomberg Opinion, November 28, 2021. ↩

-

18

Jonathan (Yoni) Shimshoni, “Swords and Emotions: The American Civil War and Society-Centric Strategy,” Survival, Vol. 64, No. 2 (April–May 2022). ↩

-

19

For example, residents of Kentucky—a Republican state—received an average of $14,000 more from Washington than they paid in taxes in 2019. See Paul Krugman, “Kentucky on My Mind,” The New York Times, December 14, 2021. ↩

-

20

See our “How Can We Neutralize the Militias?,” The New York Review, August 19, 2021. ↩

-

21

See, for instance, Heather Digby Parton, “Trump’s Troops: The Far-Right Has a Tight Grip on Too Many in Uniform,” Salon, January 10, 2022. Two US Army generals appear to have delayed the National Guard’s response to the January 6 insurrection. See Betsy Woodruff Swan and Meridith McGraw, “‘Absolute Liars’: Ex-D.C. Guard Official Says Generals Lied to Congress About Jan. 6,” Politico, December 6, 2021. ↩