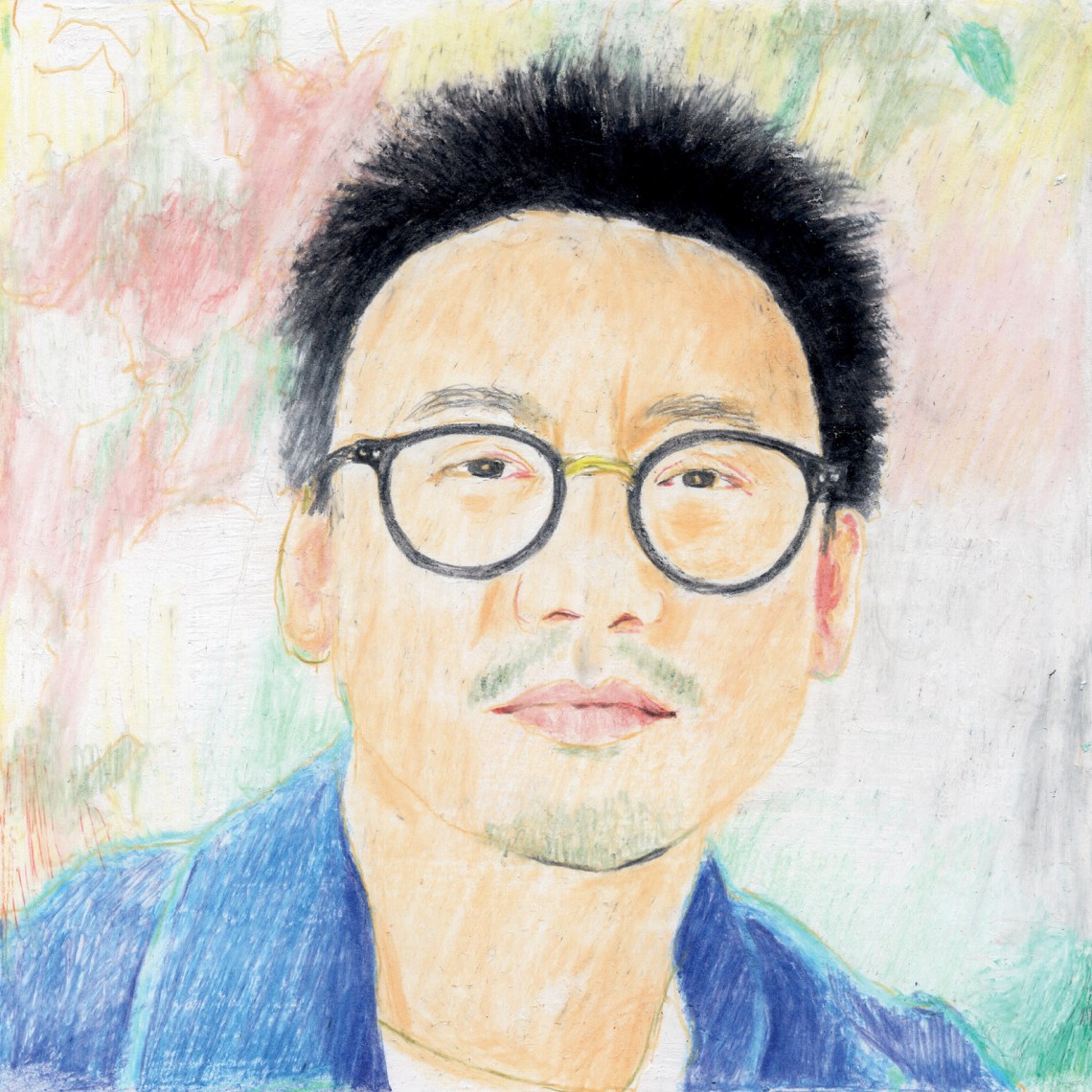

When they were undergraduates at Berkeley in the 1990s, Hua Hsu’s friend Ken was murdered, randomly and wantonly, in a carjacking. That is the precipitating cause of Hsu’s memoir, Stay True. The killing occurs a bit past the middle of the book and governs its trajectory: an edenic preamble followed by a long fall. Ken’s murder is not the subject, though, but more like the volcanic eruption that preserves in its gradually cooling ash the life that once went on. The real subject is friendship. Also youth. Also Asian identity. And incidentally zines, time, education, California, history, partygoing, menswear, mixtapes, and a dozen other matters. Hsu is never going to be the kind of writer whose books have just one subject.

Berkeley was a short hop for teenage Hsu. His parents were Taiwanese immigrants who settled in Cupertino in the early days of Silicon Valley. They met in the United States as students in the early 1970s and still retain some of that era’s political ideals, and its records. His father’s listening habits—Bob Dylan, Thriller, Guns N’ Roses, MTV—make Hsu think that music is an uncool adult thing. At some point in his teen years, his parents decide that his father will move back to Taiwan, a much more liberal country than the one he left in 1965. In Silicon Valley he had ascended to middle management but was seemingly stuck there forever, lacking the profile, racial and otherwise, to move up. In Taiwan he would have an executive position: “Never again would he have to dye his hair or touch his golf clubs.” Father and son begin communicating by fax—with voluminous faxes from Dad, patiently explaining the principles of geometry or delivering encouraging homilies.

Meanwhile young Hua is exploring the culture on offer to his generation, and before long he is absorbed in it. On the radio late one night in 1991, at the age of thirteen, he hears Nirvana’s “Smells Like Teen Spirit.” When the other kids at school don’t know what he’s talking about the next day, his having heard the song first feels like a benediction. He begins putting out a zine, writing passionate defenses of Pavement and Polvo and decrying “Beverly Hills, 90210, hippies, private school, George Bush, braided leather belts, the police state, and, after they became trendy, Pearl Jam.” “I explored the less trafficked aisles of the comic shop, rummaged through my grandparents’ apartment for old flannels, mohair ties, factory lab coats,” he writes. He has joined the ancient lineage, the seekers of the secret handshake.

So when he gets to Berkeley and starts making friends, it is not at all obvious that he will find anything in common with Ken, the tall, handsome, athletic scion of a Japanese American family from El Cajon, a suburb of San Diego, in the country for generations and correspondingly secure. Ken is loud, a frat bro who wears Abercrombie & Fitch and listens to the Dave Matthews Band: “He projected confidence. I found confident people suspicious.” On Ken’s wall is a “photo of his girlfriend back home, white and blond and conventionally pretty.”

Ken also has enormous charm and many practical skills: “He could treat a hangover, and he opened the door for others. He knew how to order at restaurants. He seemed eager for adult life.” It’s galling to Hua that Ken is from an Asian background but doesn’t act like it. “The children of recent immigrants feel discomfort at a molecular level, especially when doing typical things, like going to the pizza parlor on a Friday night, playacting as Americans,” Hsu writes. “We are certain you’ve forgotten our names…. We all look alike, until you realize we don’t, and then you begin feeling that nobody could possibly seem more different.”

The friendship persists because Ken insists on it. He knows he has a lot to learn from our narrator; he immediately senses Hsu’s proclivities for cultural exploration, his firm and sometimes eccentric tastes, his prodigious memory. Noticing Hua’s thrift-shop couture, for example, Ken asks for help shopping for what turns out to be a 1970s-themed costume party. “He was a young man, I was an old one,” Hsu writes, “and now we were sorting through secondhand polyester shirts, blazers of the deceased, dust everywhere as we shook open every new marvel.”

Hua doesn’t trust Ken at first, expecting ridicule. But although he may think Ken is condescending to him, he is himself at first very condescending to Ken, who is a great deal more perceptive and subtle than his tastes might indicate. He appreciates Hua’s labyrinthine self-protections:

Ken noticed that I never really went out. More important, he noticed that I hoped to be noticed for this. I’d never touched alcohol, but it was mostly because I was a snob, not a straight-edge ideologue. I couldn’t imagine letting down my inhibitions around people I’d be silently judging the whole time.

And Ken is no slouch on the intellectual front, either:

Advertisement

He recommended a book on hegemony and socialism by Ernesto Laclau and Chantal Mouffe. I scoffed, as if he had just praised the Pearl Jam of post-Marxist thought—Oh yeah, I’ve heard of them—and then I committed their names to memory.

Hsu seems to have total recall, and apparently some very thoroughgoing journals. He is adept at evoking the flavor of specific times and places through a pointillist buildup of small details. He conveys the quality of passing time at an age when every day brings a new lesson with lifelong reverberations: “I was actually happy today, I wrote in my journal that spring. I mean bullshit happy, that lighthearted feeling of carefree dizziness.”

New currents blow through—new people, new records, new thoughts—while to the overexcited postadolescent it all might feel like a mundane slog, just waiting for life to start for real. There is the comfort of the group, the mild adventure of driving to far-flung strip malls with his friends, the reassuring annoyance of their singing off-key over his meticulously constructed mixtapes. Throughout, Hsu is making connections between what he reads and what he is living. He decides to become a poli sci major, maybe because an observation he made in an English class was quickly dismissed, also because the school paper hasn’t published his writing.

He begins to think of race in new ways; he is, after all, in the home of the Black Panthers. While Ken, having failed an audition for MTV’s The Real World, says, “I am a man without a culture,” Hsu volunteers at a community center to work with predominantly Southeast Asian middle-school kids. Most of his charges are Mien, a repeatedly displaced people from the Laotian highlands. “The fact that we were all Asian mattered more to me than to my mentees,” Hsu writes.

As a Taiwanese American whose parents came decades earlier for grad school, I might as well have been from Mars. The boys borrowed a lot from their Black classmates, and they probably had more in common with them than with people like me.

Weaving through the story is a meditative essay on the meaning of friendship. Hsu pursues the theme from Aristotle to Derrida but finds the most useful insights in Marcel Mauss’s “Essay on the Gift.” “Mauss introduced the idea of delayed reciprocity,” he writes. “We often give and receive according to intermittent, sometimes random intervals. That time lag is where a relationship emerges.” The essay was originally published in 1923, Hsu notes, in the first postwar issue of L’Année sociologique, which begins with a lengthy memorial to the scholars killed in the war, name after name of young men with glorious ambitions, whose promise was evident to all, who might have become our greatest philologist, but who died in the trenches.

Hsu’s first book, A Floating Chinaman (2016), tells the story of H.T. Tsiang, a Chinese immigrant writer whose life story was as bitterly ironic a parable as any of his books. His novels were continually rejected by publishers, driving him to self-publication again and again, while China as a subject was thriving, selling big, as long as it came from the pen of Pearl S. Buck, whose viewpoint was missionary. Tsiang ended up as a minor Hollywood actor. Since 2014 Hsu has been a regular contributor to The New Yorker, where he covers a wide beat, centering on music and often racial matters and sometimes branching off into sports or academia. He is that rare thing: a chronicler and critic who files nearly every week while engaging fully, emotionally as well as intellectually, with every subject.

Maybe his most heartbreaking piece to date is his account of the fire that destroyed a large portion of the holdings of the Museum of Chinese in America at the beginning of 2020. These were humble items, many of them gathered through literal trashpicking:

…film reels and lobby posters from legendary Chinatown theatres; irons, washboards, spool holders, and laundry tickets; wooden dolls, a plastic toy of a man being pulled in a rickshaw, opera costumes, silk jackets, embroidered slippers; a hand-painted T-shirt from a comedy troupe that only ever performed once.

Hsu understands in his bones the importance of these objects—once everyday and now rare because it never occurred to anyone to save them—and the tragedy of their loss. “There were hand-painted signs that weren’t created as art, suitcases that were only meant for a one-way passage across the ocean, tiny mementos that outlived the reasons for their aura.” Stay True is likewise concerned with the preservation of memory, the material constituents of which turn out to be matchbooks, ticket stubs, snapshots, mixtapes, zines.

Advertisement

The night Ken died, he was having a party in his new apartment off campus—a housewarming, he called it, in very adult fashion. Hsu, who by then regarded him as an experienced elder, tried to get him aside to ask earnest questions about losing his virginity, but they were interrupted and the opportunity was lost. Ken proposed they might all go swing dancing, a pursuit of his since seeing Swingers. Hsu, embarrassed by the very idea, begged off and went with some friends to a rave in a warehouse. Driving home afterward they saw Ken’s light still on, but thought nothing of it.

When they learn about the murder, Ken’s friends all cling to one another, overwhelmed by grief, eating and sleeping and traveling as a group: “moving as a pack felt essential,” Hsu writes. They fly to San Diego for Ken’s funeral, where they are comforted by Ken’s parents. They collectively write the eulogy that Hsu delivers. He is consumed by the thought that had he swept aside his snobbery and gone swing dancing with Ken, the story might have turned out differently—not that he has any specific reason to think so besides survivor guilt. He begins wearing a hat Ken left behind, drinking the English ale he preferred. He writes to Ken, filling him in and confessing to him. By slow degrees he absorbs Ken into himself.

Anyone who has known grief knows that after the unbearable initial period of relentless sorrow, it very gradually subsides into waves that arrive further and further apart until a sort of peace settles in. That is the exact shape of the second half of Hsu’s book, as he gets his BA, has one relationship and then another, sees Ken’s killers arraigned, teaches people imprisoned at San Quentin, goes to Harvard for graduate school, spends his time rooting through new records and old books.

Hsu remembers how he and Ken were enthralled by E.H. Carr’s What Is History?, in particular this sentence: “Nothing in history is inevitable except in the formal sense that, for it to have happened otherwise, the antecedent causes would have had to be different.” During his second year of grad school he finally takes up the offer of a free semester of psychotherapy, somewhat defensively at first, until he realizes of his therapist, “She was asking, what is history? Do you see yourself in it? Where did you find your models for being in the world?”

In Stay True Hsu makes us see how his and Ken’s and their friends’ stories are tossed on the sea of history, how identity takes shape from a thousand factors, how personalities flow into one another, how chance and destiny can be hard to tell apart. He had to write the book to perpetuate Ken and bring him to the attention of the world. To do so, he discovers, he had to

figure out how to describe the smell of secondhand smoke on flannel, the taste of pancakes with fresh strawberries and powdered sugar the morning after, sun hitting a specific shade of golden brown, the deep ambivalence you once felt toward a song that now devastated you, the threshold when a pair of old boots go from new to worn, the sound of our finals week mixtape wheezing to the end of its spool.

This Issue

November 24, 2022

Khamenei’s Dilemma

Georgia’s Battle Over the Ballot