Kafka wrote bedtime stories in the sense that he wrote about the terrifying things that might happen in bed. No sooner has the father in “The Judgment” pulled the covers high over his shoulders than he condemns his son to death by drowning; the doctor in “A Country Doctor” is tucked in by the villagers beside a patient with a worm-ridden wound in his side; the huge stoker in “The Stoker” suggests to Karl, lost in the bowels of the ship, that he stretch himself out on the bunk because “you’ll have more room there.” K. in The Trial is in bed when they come to arrest him, and Gregor Samsa in “The Metamorphosis” is transformed overnight into a “monstrous vermin,” first discovering his new shape when he wakes up in bed. As for the intimacies of married life, Kafka’s horror is summed up in his diaries by his mention of “the sight of the nightshirts on my parents’ beds.”

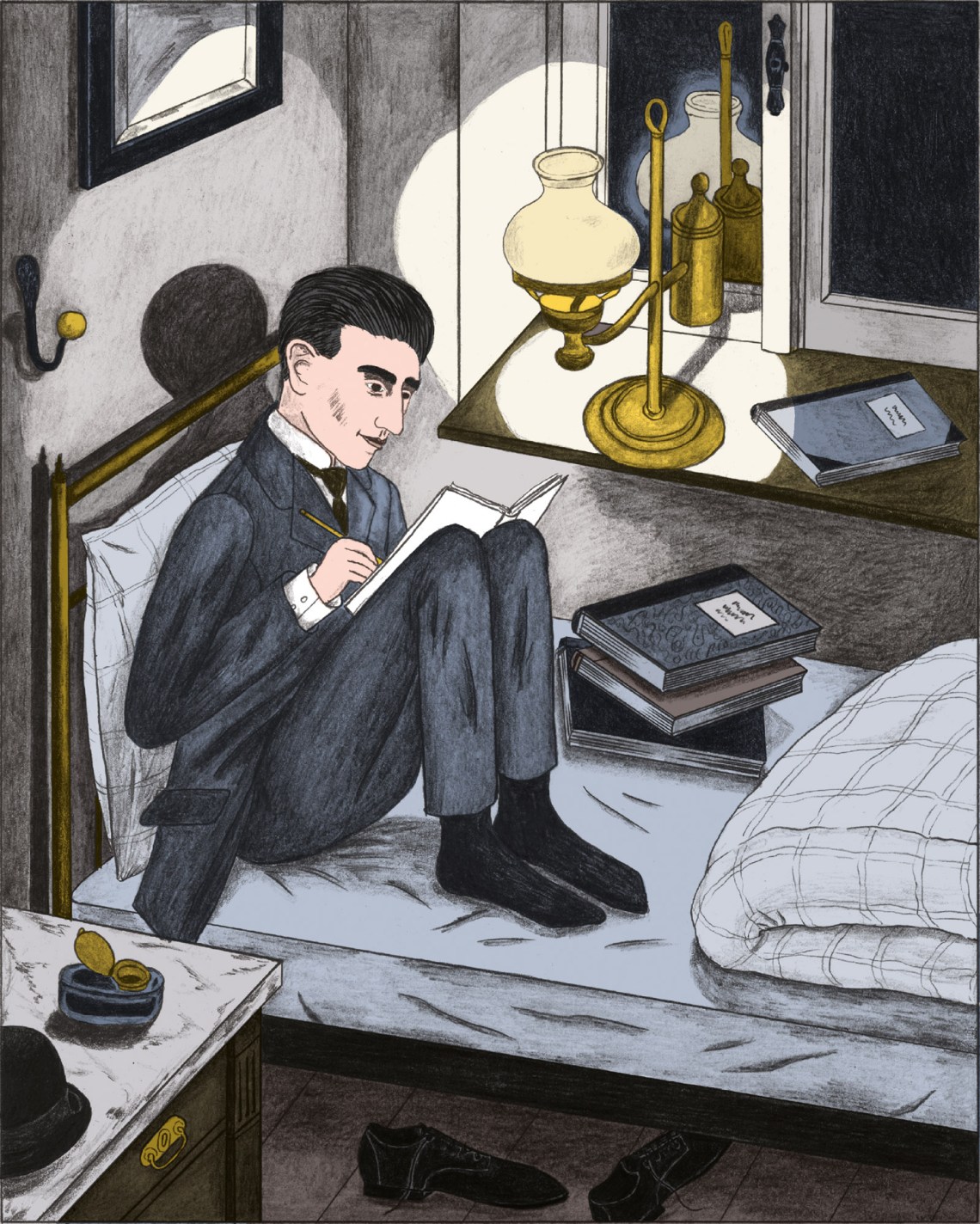

He also wrote his stories at bedtime. This is because he had difficulty sleeping—but he had difficulty sleeping, he realized, because he wrote, which made him susceptible to the kind of states “that would tear me open and could make me capable of anything.” Writing involved a fight that Kafka rarely won. In his diaries’ opening pages he describes writing as having to be “wrested from me, from this heap of straw that I have been for five months and whose fate, it seems, is to be set alight in the summer and to burn away before the spectator can blink.” Sitting at the desk in his bedroom at 10:00 PM on November 15, 1910, he reported on his attempts to write a second version of “Description of a Struggle”: “I won’t let myself get tired. I will jump into my novella even if it should cut up my face.”

Kafka wrote at bedtime because his stories were “a kind of closing one’s eyes,” and he needed to reach a semiconscious state in order to draw from the depths. He therefore observed himself like a watchman (“Someone must watch…. Someone must be there”) even as he slept. “I am practically sleeping next to myself,” he wrote on October 2, 1911, and he felt he was writing into the darkness as though into a tunnel. “When I can’t chase the stories through the nights,” he recorded on January 4, 1915, “they escape and get lost.” When his fiancée, Felice Bauer, suggests in a letter that she keep Kafka company, he sends her a panicked reply: “One can never be alone enough when one writes…there can never be enough silence around one when one writes…even night is not night enough.”

He had other reasons for writing at night, such as his day job at the Workers’ Accident Insurance Institute, where he handled appeals and processed compensation claims. It was a job he loathed but was afraid to leave because he doubted his ability to support himself by literature alone, although he lived for almost all of his forty years with his middle-class parents (a further reason for confining himself to his bedroom) in central Prague. Despite his aversion to his bullying father and the dullness and claustrophobia of family life, Kafka couldn’t risk leaving home because of his health, which he believed, long before he became tubercular in his mid-thirties, to be fragile. (“With such a body nothing can be achieved,” he wrote in November 1911.)

These were the Promethean conditions he chose for himself because daily anguish, entrapment, and unresolvable obstacles were essential to the special nature of his work, whose central comedy, or tragedy, is that being bound to a rock is unbearable but being unbound is even worse. His writing therefore kept alive the hatreds of his father, his job, and his goldfish-bowl existence. “I’m living as unreasonably as possible,” Kafka wrote on August 15, 1912, which might serve as the diaries’ epigraph.

Diary writing is itself, habitually, a nocturnal activity, and Kafka’s Tagebücher, as he called the twelve quarto notebooks and two bundles of loose pages in which he observed “this creature on the ground which is me,” follow the logic of his night-watching.

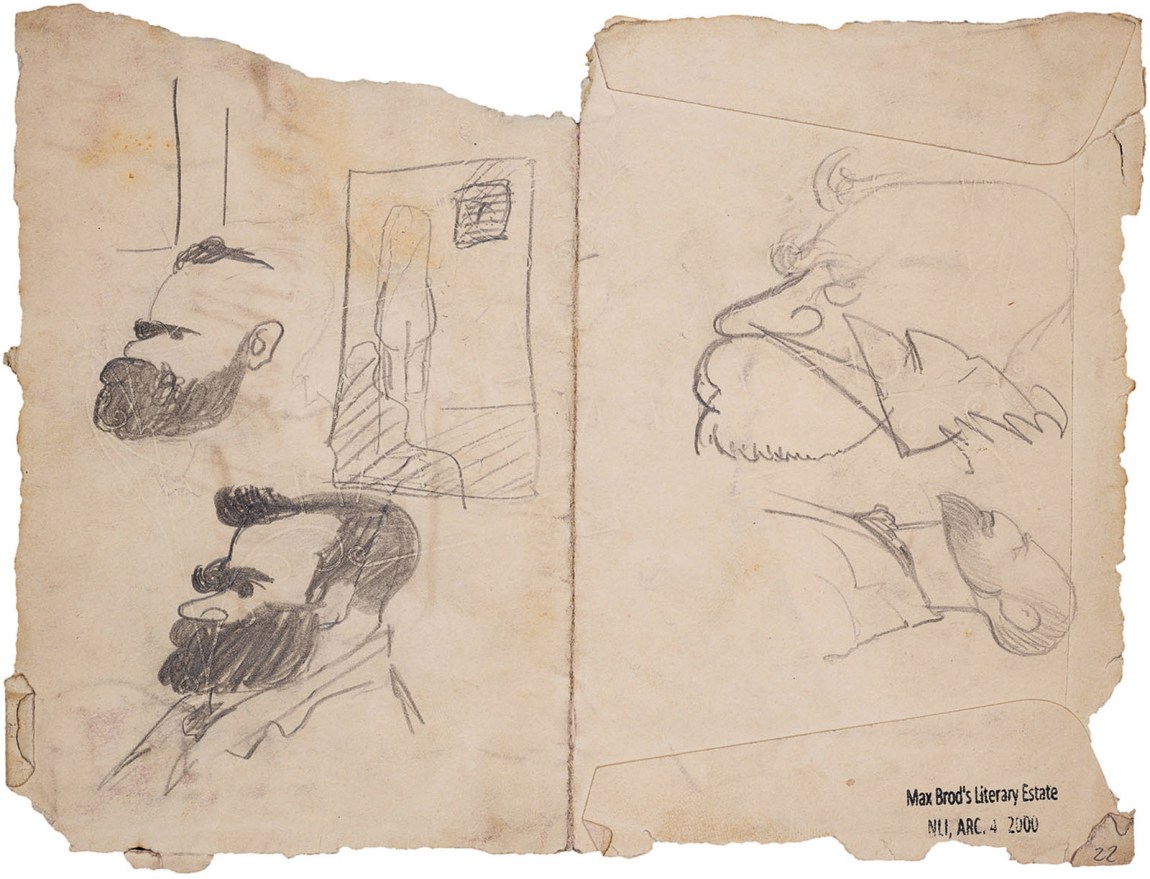

Beginning in 1909 when he was twenty-five and ending in 1923, the year before his death from tuberculosis, the diaries are made up of false starts, stray thoughts, self-doubts, internal dialogues, dreams, doodles, insertions, marginalia, aphorisms, drafts of letters, drafts of stories, self-reflections, reconstructions, character sketches, and scenes from family life that, like this entry from December 10, 1911, are often very funny:

When my mother returned from my sister the day before yesterday at 1 o’clock at night with the news of the boy’s birth, my father moved through the apartment in his nightshirt, opened all the doors, woke me the maid and my sisters and announced the birth in such a way as if the baby had not only been born but had also already led an honorable life and had its funeral.

It was Max Brod, a fellow student at Prague’s Charles University, where Kafka studied law between 1901 and 1906, who encouraged him to keep the diaries. Kafka was shy and diffident and Brod, his closest friend, first reader, and, later, literary executor, was fluid and confident; before his name was attached in small print to Kafka’s own, Brod was the celebrated writer and Kafka the acolyte. The seriousness with which Kafka treated his task can be seen by his close reading of other diaries, such as Goethe’s, which he particularly admired. “Read Goethe’s diaries a little,” he wrote on December 19, 1910. “The distance captures this life already calmed, these diaries set fire to it. The clarity of all the events makes them mysterious, just as a park fence gives the eye rest in contemplation of vast fields of grass and yet inspires our inferior respect.” Dorothy Wordsworth kept her modest journals of life in Grasmere in order to give her brother William “pleasure,” and Kafka’s diaries were written, at least in part, to give pleasure to Brod. “New Year’s Eve,” Kafka wrote at the close of 1912:

Advertisement

I had planned to read to Max from the diaries in the afternoon I had been looking forward to it and didn’t manage to do it. We didn’t feel in harmony, I sensed in him that afternoon a calculating pettiness and haste, he was almost not my friend, but still dominated me to the extent that I saw myself through his eyes leafing uselessly through the notebooks again and again and found this leafing back and forth, which showed the same pages flying by again and again, abhorrent.

Despite his deathbed instruction that the diaries, which he considered worthless, be burned along with his other unpublished material (effectively his entire oeuvre), Brod preserved all Kafka’s manuscripts, taking them with him to Palestine in a suitcase when the Nazis occupied Prague in March 1939. Having first ensured Kafka’s fame through the publication of the novels and stories, Brod then prepared the diaries for press, bowdlerizing them in the process. They appeared in English in two volumes in 1948–1949, the first translated by Joseph Kresh and the second by Martin Greenberg and Hannah Arendt. In homage to his friend, Brod replaced the comic self-portrait of the anxious author leafing uselessly through his notebooks with a more streamlined, serious, and altogether less vital figure.

Kafka saw his work as broken, unfinished, and fragmented. The diary entry for November 5, 1911, describes the “bitterness” he felt hearing one of his stories read aloud by Brod:

The disordered sentences…with gaps through which one could stick both hands; one sentence sounds high, one sentence sounds low as the case may be; one sentence rubs against the next like the tongue against a hollow or false tooth; one sentence comes marching up with so rough a beginning that the whole story falls into morose astonishment.

In the diaries such rough, atonal, and potholed sentences were smoothed by Brod into a coherent narrative; he cut passages, constructed paragraphs, erased the lines Kafka had drawn between various entries, added dashes at the ends of sentences Kafka had left without periods (suggesting, therefore, a suspended rather than a discarded thought), altered real names to protect identities, censored sexually explicit content as well as content that might reflect unfavorably on Brod himself. He ironed out the Austrian, Jewish, Czech, and Prague-German inflections (Kafka, like Brod, was a German-speaking Jew in a principally Czech-speaking Catholic city; he was fluent in Czech and he spoke Yiddish) in order to present his voice in High German. He organized the textual chaos of the notebooks into chronological chapters titled “Diaries 1910,” “Diaries 1911,” and so forth, adding subtitles that referred to subject matter (“The Dancer Eduardova,” “My education has done me great harm”). He cut words that seemed to him nonsensical, such as Notstich (translated here as “emergency puncture”), which Kafka used on February 15, 1914, in a sentence that would otherwise read: “Met Krätzig in the tram ‘emergency puncture.’”

Brod rationalized the entries’ elliptical and cryptic system of dating—Kafka often wrote the day and the year in Arabic digits and the month in Roman numerals (his “19 II 11” becomes Brod’s “19 February” in the section “Diaries 1911”)—and silently corrected the days and months that Kafka, in his haste and exhaustion, got wrong. “The text of the diaries,” Brod explained with breathtaking disingenuity, “is as complete as it was possible to make it.” Not only did he harmonize what Kafka called “the general noise that is in me,” he got rid of the textual cacophony that reminds us that the diary is the work of a living hand.

Advertisement

Brod’s editorial interference is exasperating, and Ross Benjamin, whose translation is the first complete and uncensored edition of the Diaries to be made available to an English readership, is duly exasperated. Basing this new version on the German critical edition published by S. Fischer Verlag and edited by Hans-Gerd Koch (1990), with 1,403 abridged and adapted endnotes, Benjamin begins from scratch the whole business of restoring to the notebooks their “provisionality, materiality, and mutability,” including the impossible-to-follow dates. His loose-limbed translation gets off on exactly the right note with the first entry, which replaces Kresh’s “The onlookers go rigid when the train goes past” with “The spectators stiffen when the train passes.” Kafka always had devastating opening lines.

Benjamin’s aim is to give us the writer in his “workshop,” blotting the page, changing his mind, running at a sentence a dozen times and still not getting it right. He therefore maintains the hasty punctuation, garbled syntax, indecipherable ideas, and slips of the pen, keeping the various spellings of New York (“Newyork,” “Newyorck,” “Newyort”). Replacing Brod’s chronological reordering with sections titled “First Notebook,” “Second Notebook,” and so forth, Benjamin restores Kafka’s not inconsiderable textual confusions together with the passages Brod chose to cut. “First Notebook,” for example, contains entries written between May 1910 and October 24, 1911, while “Second Notebook” begins with a draft of “Unhappiness” (published in Kafka’s first collection of stories, Betrachtung, translated by Benjamin as Contemplation and by Malcolm Pasley as Meditation), followed by entries written between November 6, 1910, and March 1911, after which there is the continuation of “The Stoker” (the first chapter of Kafka’s unfinished novel Der Verschollene, translated by Benjamin as The Missing Person as against Pasley’s superior, to my ear, The Man Who Disappeared, and renamed Amerika by Brod).

Der Verschollene was begun in late September 1912 in the sixth notebook before Kafka ran out of space, continuing it in the blank pages at the end of the second notebook. The third notebook then starts on October 26, 1911. Brod, who deals with the muddle by getting rid of the second notebook altogether and then stitching the October 26, 1911, entry immediately after the October 24 entry (at the end of the first notebook), can be forgiven for cutting and pasting the text into a sequence that makes sense to the reader. Benjamin’s edition, effectively a facsimile of the notebooks themselves, offers us another order of experience entirely; it is less like peeking into a messy bedroom than finding yourself in one of Piranesi’s imaginary prisons, a torture chamber without entrance or exit, walls or ceilings, with flights of stairs going everywhere and nowhere. The difference between the Benjamin and Brod editions is like night and day.

The theme of Kafka’s diaries, because diaries have themes, is the fear of writing and, necessarily, of not writing. “Wrote nothing,” he records on August 10, 1912. “Nothing, nothing,” he repeats on August 11. On August 13 he meets for the first time Felice Bauer, to whom he will twice become engaged, but the encounter is not recorded until August 20, when he describes her appearance: “Bony empty face, which wore its emptiness openly…. Almost broken nose. Blond, somewhat stiff charmless hair, strong chin.”

On September 18 Kafka notes down what he hears in the office about how to eat a live frog and the best way to kill a cat (“One squeezes the neck between a closed door and pulls on the tail”). On September 19 he gives a detailed account of two boys who drink congealed goose blood in coffee. And then, during the night of September 22–23, he writes “The Judgment”:

It was on a Sunday morning at the height of spring. Georg Bendemann, a young businessman, was sitting in his private room on the second floor of one of the low lightly built houses that extended along the river.

Georg has finished a letter to his friend who now lives in St. Petersburg; he needed to tell him that he has become engaged to a young woman named Frieda Brandenfeld from a well-to-do family. With the letter in his pocket, he checks on his elderly father in the next room. His father, sitting in the dark like “a giant,” refuses to believe in the existence of Georg’s friend and accuses his son of other deceptions besides. Concerned that the old man is getting overwrought, Georg carries him in his arms and places him in bed. Getting into bed transforms us—“No sooner was he in the bed than everything seemed good”—but it is now that the father utters his terrible curse: “I sentence you…to death by drowning!” Propelled by an extraordinary force, Georg leaves the apartment and crosses the road to the water where he swings himself over the railing and “let[s] himself fall.” “At that moment,” Kafka wrote in the story’s final sentence, “a positively endless stream of traffic was going over the bridge.”

Brod cut from his edition of the diaries this word-perfect first draft of the “The Judgment,” presumably because it had been published already in the June 1913 issue of the journal Arkadia, which he also edited. The omission (repeated with “The Stoker,” a story Kafka began two days after “The Judgment”) is like removing a nose from a face. The stories grew spontaneously out of the notebooks, and the restoration of “The Judgment” allows us to be present at what Kafka described on February 11, 1913, as a “veritable birth covered with filth and slime.” We witness not only the birth of his story, but the birth of Franz Kafka himself. The night of September 22–23, 1912, was Kafka’s own metamorphosis, when he drew from the depths the full possibilities of his writing.

The following day’s diary entry describes, in what is effectively another story, the labor pains (“Only I have the hand that can penetrate to the body and has the desire to do so”):

This story “The Judgment” I wrote at one stretch [in einem zug—literally: “on one train”] on the night of the 22 to 23 from 10 o’clock in the evening until 6 o’clock in the morning. My legs had grown so stiff from sitting that I could hardly pull them out from under the desk. The terrible strain and joy, how the story unfolded itself before me how I moved forward in an expanse of water. Several times last night I bore my weight on my back. How everything can be risked, how for all, for the strangest ideas a great fire is prepared, in which they die away and rise again. How it turned blue outside the window…. The appearance of the untouched bed, as if it had just been carried in…. Only in this way can writing be done, only with such cohesion, with such complete opening of the body and the soul. Morning in bed…thoughts of Freud naturally…

His thoughts of Freud continued on February 11, 1913, when Kafka, correcting “The Judgment” for publication, probed his unconscious as though analyzing a dream:

The friend is the connection between father and son, he is their greatest commonality. Sitting alone by his window Georg rummages voluptuously in this commonality, believes he has his father in himself and regards everything as peaceful but for a fleeting sad reflectiveness. The development of the story now shows how from the commonality, the friend, the father rises forth and sets himself up in opposition to Georg.

Apologizing in the postscript to his own edition for the darkness of the diaries, Brod reassures us that gloom was not Kafka’s only mood. His “good humour,” says Brod, can be seen in the travel journals (included in Benjamin’s edition) and the letters to Felice. Diaries, Brod reminds us, can give a “false impression” because we tend to record what is “oppressive or irritating”; they therefore “resemble a kind of defective barometric curve” that registers the lows but not the highs.

The blackest band of the barometric spectrum has never been my experience of Kafka’s diaries, which I have always found elevating, energizing, and utterly joyful, with Benjamin’s wild edition increasing my pleasure tenfold because he allows us to encounter them in their complete heroic excess. Kafka’s diaries—in which it is often unclear whether what we are reading is a factual account or fictitious reverie—contain too much, they go too far, they break the sound barrier of self-reflection and allow a glimpse of what writing can be. Like The Thousand and One Nights, they are a potentially infinite book, and it only ends because Kafka reaches, in 1924, the zenith of his life.

His diaries make me laugh, and I believe I am laughing with him. His style reminds me of something Anthony Powell once said: “Any piece of human behaviour will seem absurd if described precisely enough.” Kafka’s “inescapable duty of self-observation,” as he called it in one of his final entries (November 7, 1921), frequently seems absurd. Take the entry for December 11, 1913:

When I imagined today that I would definitely be calm during the presentation, I asked myself what sort of calm it would be, on what it would be based, and I could say only that it would merely be a calm for its own sake, an incomprehensible mercy, nothing else.

The self here is studiedly performative. Kafka was fascinated by theater; the second notebook is taken up with his visits to a Yiddish theater troupe from Lemberg, in Prague between September 1911 and January 1912, with whom he became friends. The entry describing the formal dissolution of his first engagement to Felice on July 23, 1914, is set out as stage directions:

The tribunal in the hotel. The ride in the carriage. F.’s face. She runs her hands through her hair, wipes her nose with her hand, yawns. Suddenly gathers herself together and says well-thought-through, long-saved-up, hostile things.

Entries such as “Sunday, 19 June [19]10 slept woke up, slept, woke up, miserable life” are the sort to be found in Sue Townsend’s The Secret Diary of Adrian Mole, Aged 13¾—a novel that, in its fond parody of an angst-ridden teenager with intellectual pretensions, might have been inspired by Kafka, who identified with moles. His final story, “The Burrow,” written six months before his death, is the monologue of a mole-like creature with excessive reasoning powers (“You do not know me if you think I am afraid, or that I built my burrow simply out of fear”). Kafka’s animal alter egos are always wittily done. “Was together with Blei, his wife & his child, at times heard myself in myself,” he notes on May 18–19, 1910, “roughly like the whimpering of a young cat.” “I’m really like a lost sheep in the night,” he writes on November 19, 1913, “or like a sheep that is running after this sheep.”

Describing himself both as others see him (“leafing uselessly through the notebooks again and again”) and also as his own double, Kafka created self-perspectives that, like his cartoon-style doodles, are elongated, foreshortened, and frequently surreal—these are now, for the first time, collected in their entirety in the magnificent Franz Kafka: The Drawings, edited by Andreas Kilcher.* “Yesterday evening on Mariengasse I held out both my hands to both my sisters-in-law at the same time with an adroitness as if they were two right hands and I a double person.” Then there are the Jewish jokes: “What do I have in common with Jews? I have scarcely anything in common with myself.” It is easy here to imagine the laughter of Kafka’s friends. Equally comic are the arguments for and against marriage to Felice. Number one on the list, “Inability to endure life alone”—Kafka’s only argument in favor of the marriage—is followed in the next six entries by his fear of never being alone again.

His account, in late March 1911, of an audience with Rudolf Steiner in his hotel room after hearing him lecture on the occult, is written as a one-man show. Kafka consults the theosophist as though, like Sigmund Freud or Sherlock Holmes, he held the key to unlocking an otherwise unsolvable problem. To show “humility” on arrival, Kafka looks for a “ridiculous place” to put his hat, which he finds on “a small wooden stand for lacing boots.” He then, “facing the window,” “press[es] forward” with a long and convoluted “prepared speech” that he frames as a question. The gist of it is that he feels attracted to theosophy but at the same time afraid of it:

I’m afraid, namely, that it will bring about a new confusion, which would be very bad for me since my present unhappiness itself consists of nothing but confusion. This confusion lies in the following: My happiness, my abilities and any possibility of being in some way useful have always resided in the literary realm.

What follows is a tangled account of the dreariness of his day job and the requirements of his night job, together with the well-rehearsed reasons why he can’t leave the insurance office and devote himself to writing. Kafka’s question, tagged onto the end of the monologue, is whether Steiner thinks it wise to add theosophy as a third problem to “these two never-to-be-balanced endeavors…. Will I, already at present such an unhappy person be able to bring the 3 to a conclusion?” All the while, not looking at the anxious young man, Steiner works his handkerchief “deep into his nose, one finger at each nostril.” Kafka’s attention to noses is a rich vein in his comedy.

Nothing more is said in the diary about either Steiner or theosophy, but a similar encounter can be found in “A Report to an Academy: Two Fragments,” a story Kafka drafted in April 1917. Having seen the world-famous Rotpeter onstage, the narrator meets him in his hotel room the next day: “When I sit opposite you like this, Rotpeter, listening to you talk, drinking your health, I really and truly forget—whether you take it as a compliment or not, it’s the truth—that you are a chimpanzee.”

I am not alone in thinking Kafka a comic genius. He was “known,” he told Felice, “as a great laugher.” He worked himself “into a frenzy” when he read “The Metamorphosis” to Brod and his circle, an occasion when everyone let themselves go “and laughed a lot.” Brod describes, in his Biography of Franz Kafka, being part of a group that “laughed quite immoderately” when Kafka read aloud the first two chapters of The Trial; Kafka himself was laughing so much that he had to stop reading altogether.

In a 1998 speech called “Some Remarks on Kafka’s Funniness from Which Probably Not Enough Has Been Removed,” David Foster Wallace said that he gave up teaching Kafka because his students didn’t get the central joke, “that the horrific struggle to establish a human self results in a self whose humanity is inseparable from that horrific struggle.” But even if we do understand the joke, laughing at Kafka’s diaries has, until now, felt like a misreading because Brod projected his own seriousness onto his friend. Ross Benjamin’s carnivalesque translation licenses our laughter by confirming, as Kafka put it in The Trial, that “the right perception of any matter and a misunderstanding of the same matter do not wholly exclude each other.”

This Issue

April 6, 2023

Becoming Enid Coleslaw

Putin’s Folly

-

*

Yale University Press, 2022. ↩