We are living, as we know, through a global water crisis. Climate change has brought droughts to large areas and floods to others; water scarcity has led to the privatization of this precious commodity in some countries, and with it an increased economic burden on the poor; factory runoff and aging lead pipes contaminate drinking water; regions and nations fight over the allocation of river rights, as do agricultural and urban interests. Given the complexity of land use and water politics, it seems almost a miracle that residents of New York City can rely on a dependable stream of clean, good-tasting water in their daily lives. This water comes from a network of upstate artificial lakes whose development over the past 180-odd years Lucy Sante charts in her new book, Nineteen Reservoirs.

Lest one expect a paean to American ingenuity, the author’s attitude toward this achievement is not exactly celebratory—it’s rather elegiac, in fact. “The reservoir system has been a great success,” she acknowledges, and “continue[s] collectively to supply the city with more than 1.1 billion gallons of fresh water every day.” But that success has come at a price. “From an upstate perspective,” Sante writes,

the reservoir system represents at best an imposition and at worst an imperial pillage of the landscape. Twenty-six villages and countless farms, orchards, quarries, and the like were bought for a fraction of their value, demolished, and then submerged, some of them within living memory, leaving broken hearts and fractured communities. The system has further affected a political polarization between upstate and down, city and country, that was already well underway before the first shovel of soil was removed, and which appears as a microcosm of the urban/rural polarity that continues to unbalance the nation as a whole.

Her “purpose,” she continues, “is not to condemn the reservoir system.” Without it, the city

might have faded into insignificance over the course of the twentieth century, not only squelching its vast financial powers but aborting its function as shelter for millions of people displaced from elsewhere.

What she intends is more balanced: “I would simply like to give an account of the human costs, an overview of the trade-offs, a summary of unintended consequences.”

The book proceeds chronologically through the construction of the main reservoirs: first the Croton system east of the Hudson, then the “six great reservoirs”—Ashokan, Schoharie, Rondout, Neversink, Pepacton, and Cannonsville—to the river’s west.* Most historical accounts of New York focus on the hoopla surrounding the arrival of Croton water in 1842, but Sante says little about this response, concentrating instead on what she sees as the pattern for all

water-utility projects to come: recalcitrant landowners, aggrieved landowners feeling cheated by their remuneration (some land was bought for $160 an acre and some for $565 an acre), labor disputes, ethnically based disputes among workers, outbreaks of disease, fatal blasting accidents, and innumerable delays.

Sante is a zealous researcher, as is amply demonstrated by her first book, Low Life (1991), that marvelous compendium of vice and chicanery in nineteenth-century New York City. In Nineteen Reservoirs she has once again dived deep into the archives, ferreting out intriguing nuggets and vignettes from the newspapers and court filings of the day, as well as an illuminating trove of illustrations. We learn, for instance, of the often unavailing efforts to reduce water waste by installing universal metering—a practice first proposed in the 1860s and later resisted by landlords, who feared that their tenants would maliciously overuse water in order to drive up their bills.

Progressives also fought meters, seeing them as a tax on the poor. Reform mayor William Jay Gaynor used the slogan “Water must be as free as air” in 1912, and decades later, in 1965, Mayor Robert Wagner was still insisting that free and unlimited water was “a part of the social philosophy of the people of the city” and “a mark of our social advance.” The problem was that New Yorkers seemed to be fairly profligate in their use of water, consuming nearly four times as many gallons per day per capita as Londoners.

The vast expansion of the city’s population at the turn of the twentieth century necessitated a comparable increase in the number of reservoirs—or so the logic of the times went, though rural homeowners in the path of demolition argued that the city should instead use water more frugally, or even desalinate water from the Hudson River, as many smaller municipalities were already doing for drinking purposes. But in 1950 the director of laboratories for the Bureau of Water Supply, Benjamin Nesin, said that such a plan was “‘hazardous and unreliable,’ adding, ‘The Hudson River is virtually a reservoir of infection.’” Whether this was true is beside the point, since the water would have been filtered to avoid infection, but a more subtle argument against using Hudson River water was that it never tasted as fine as New York City’s tap water issuing from the lakes, and so that superb taste was fortuitously preserved.

Advertisement

In spite of the occasional curious detail, there is little to differentiate the various chapters from one another. Sante plods dutifully through the statistics of each construction job—so many feet of concrete, types of bedrock, numbers of workers—and mentions the high points (“eighteen miles long, this would be the longest continuous tunnel in the world”), but she has little feeling for the romance of engineering. In an apologetic, self-mocking aside, she even expresses boredom and skepticism about the effect of these quoted statistics:

The grandeur of the project—and those that would follow it—was invariably expressed in figures. That was the poetic language of enterprise in the twentieth century. Nothing else conveyed so well the immensity of every new undertaking and its dwarfing of whatever had preceded it, and it could be appreciated by the average piker with a fourth-grade education. Nowadays numbers have become so large they usually dissolve into abstraction.

In fact, there is an air of abstraction about this slender book, which may issue from its being strangely unpeopled. Especially compared with Low Life, so filled with juicy portraits of con artists, corrupt politicians, master thieves, and scoundrels, the prose here is less dramatic and energetic. There are no heroic visionaries like the Brooklyn Bridge’s Washington Roebling or the Suez Canal’s Ferdinand de Lesseps. No one is seen to be in charge; rather, the projects are put on the planning board and accomplished in the course of time, almost like an inexorable, impersonal tsunami washing over the countryside. The only human voices we hear at length are occasional quotes from the rural victims whose way of life is being swept away, such as the unidentified woman who told a reporter, “When they wipe out a whole community—your friends, neighbors, stores, merchants—there’s no amount of money that can replace it.” But even they are not fully individualized.

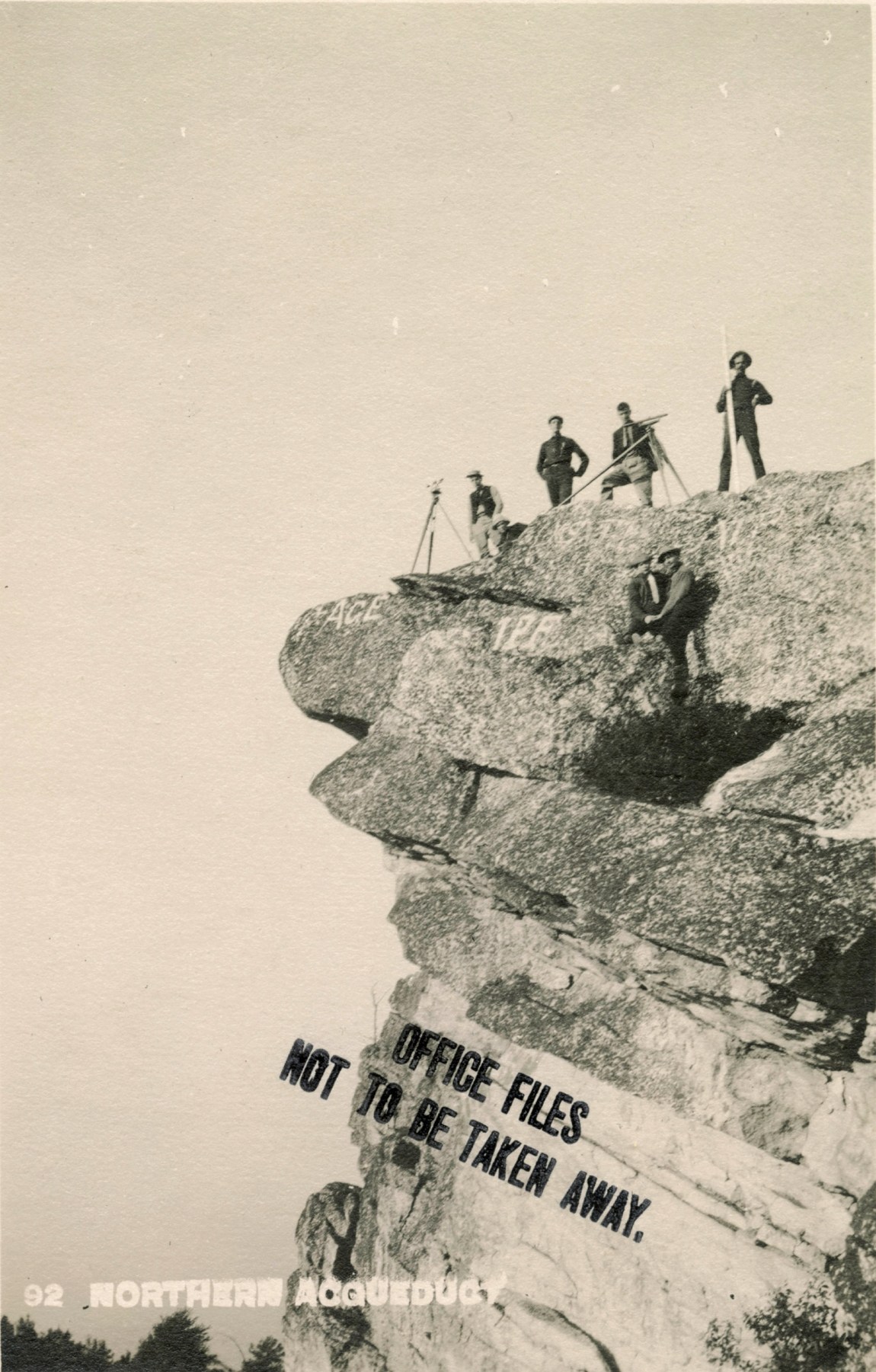

It is perhaps inevitable that Sante’s efforts to reimagine the way of life that once obtained in these small, effaced villages would be undernourished, given the scarcity of the archives left behind. Indeed, the image record she found in local newspapers and construction companies’ files seems to be a lot more robust than any verbal accounts that survived. Sante has located a prodigious vein of apt reproductions and salted them into the pages of the book. There are panoramic views of mountain valleys before the flood, postcards, tunnel interiors, pipelines, cranes, bridges, engravings, maps, placards, main streets, grocery stores, dams, waterfalls, group portraits of workers at company picnics, sandhog teams, surveyors, groundbreaking ceremonies, pumping stations, cemeteries—mostly in black and white. Added to these historic images is a set of handsome color photographs by Tim Davis, commissioned for the book, which display craggy landscapes and recreational campsites and town meetings, among other contemporary scenes.

The book’s one dominant character, you might say, is New York City, a villainous, shadowy presence pulling the strings, its attitude toward the upstate locals summarized by the author as “imperious, exploitative, cold.” In the preface to Low Life, Sante said her book was “an expression of love and hate, as is appropriate for a work about New York.” In Nineteen Reservoirs, one can no longer detect any love for the city—or hate, for that matter—only a kind of weary reproach.

What drew Sante, such a brilliant, cosmopolitan cultural critic, to write this particular study? Granted, the subject is important and has never been given fair treatment, but what do New York’s water projects actually signify for her—why does she care so much about these reservoirs? It is not until halfway through the text that we get our first partial answer, with the introduction of that first-person figure, the author:

In the 1990s, I lived not far from the Pepacton Reservoir, the existence of which I barely knew before I got there, despite having spent the previous twenty-five years as its beneficiary in New York City. Within a month or so of taking up residence in Delaware County, I was struck by the local attitude toward the reservoir. Its construction was spoken of as if it were a disaster—a volcanic eruption, say—that might have occurred decades previously but whose consequences resonated into the present day….

For the past twenty years, I’ve been living close to the Ashokan Reservoir, where the upheaval of construction occurred more than a century ago. Immediate passions may have died out with the generation that experienced the building of Ashokan, but the city is still regarded as an occupying power—like the United States military in Japan, say—that profits from the region while offering little in return and definitely not keeping the best interests of the locality in mind.

Sante tries to imagine what village life was like—the dairy farms, the churches, the scenic views drawing tourists—before these hamlets were flooded. She cites with outrage an 1886 paper by one R.D.A. Parrott, “The Water Supply for New York City,” which argued that it was all right to seize the land by eminent domain because “the Catskill territory in question suffered from ‘backwardness’ with regard to population increase.” And she notes how violent those seizures could be. In Gilboa, she writes, residents

Advertisement

put up fierce if ineffectual resistance, relying on the fact that city employees could not legally enter their houses to turn them out. When people refused to move, however, workers tore off their roofs. Even then some hung on, in empty houses, having prudently removed their furniture. Mary Brooks stood firm until she had to leave for a minute to confer with a neighbor, whereupon workers set her house on fire.

But Sante also admits that some of these villages might have disappeared even without reservoirs being constructed: their economy was frequently tied to timber, which, once depleted, gave way to farming, but the soil was too stony and the topography too variegated to be well suited for agricultural use. So the larger underlying subject, typical of this author, has less to do with the intrusion of a quasi-military bully than with the way the more or less effaced past continues to haunt the oblivious march of progress. “I’ve always been a sucker for tales of lost civilizations, pockets in time, suppressed documents,” Sante admits in her beautifully written memoir The Factory of Facts (1998).

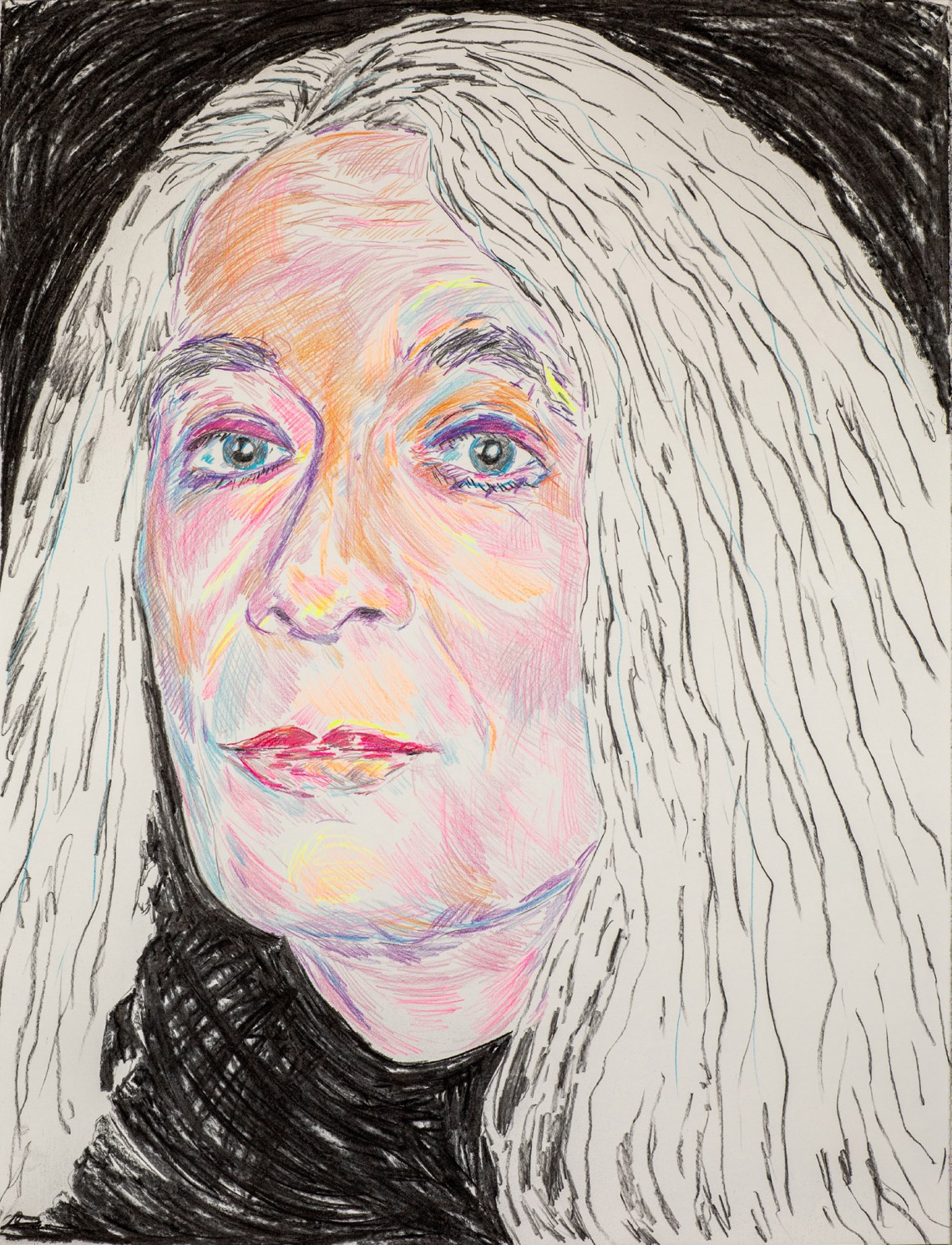

“Every human being,” she writes elsewhere in that book, “is an archeological site.” Born in 1954 in Verviers, Belgium, Sante, who came out as trans in 2021, sets out in The Factory of Facts to uncover her family’s roots in the old country and the unsettling discontinuities in their identities while restlessly migrating between Belgium and the United States. Is she European or American? “I went from being the little Belgian boy, polite and diffident and possessed of a charming accent, to a loutish American adolescent.” But the past kept drawing her back. Living as a bohemian, Beat-inspired writer in the 1980s,

I developed a consuming interest in the turn of the last century, prompted in part by the place where I was living, the Lower East Side of New York City, where every hundred-year-old tenement shell, with its scalloped cornice and ornately detailed window frames ornamenting vacancy and rot, appeared on my retina accompanied by a grimly ironic caption: the nineteenth century. I was haunted by those ruins.

Out of that fascination and research came Low Life, a book that resisted New York City’s “bulldozing of what has faded to make way for the next thing, the thing after that, the future.” She was interested in the city’s ghosts: “New York’s ghosts are the unresting souls of the poor, the marginal, the dispossessed, the depraved, the defective, the recalcitrant.” Having resurrected those ghosts to her satisfaction, Sante went on to explore the Belgian dead:

I already had a history, intriguingly buried. It might even be an interesting one. Eventually I came to the conclusion that if I did nothing else, I at least needed to uncover it. Maybe some of what I thought I had lost was merely hidden.

Digging into her mother’s ancestry of poor farmers, Sante came to a conclusion: “I am three-quarters peasant.” Here we may glimpse the source of her identification with the rural folk who lost their land to the city slickers. Though in The Factory of Facts she admits that at first “it’s much harder to insert my imagination into that world of fields and forests” than into the streets of New York, she goes on to say that Belgium isn’t so far away:

I can just drive three hours to the western foothills of the Catskills and there I can see the Ardennes, if I take the trouble to place a steeple every few feet along the horizon. To further the verisimilitude, I go on: I triple the population, dispense with isolated farms and put villages in their stead, reduce each herd of livestock by two-thirds or more but multiply the number of herds, remove most of the deciduous trees—nearly eliminated by invading Germans—and replace them with conifers, add various single-lane roads and unpave many of the ones existing, turn wooden houses to stone and convert trailers into either shacks or pre-fab units depending on which historical era I’m aiming for. But I don’t have to alter the hills, which are old and low, and the valleys steep, and the rain and fog plentiful.

What I find most intriguing, in searching for ways to link this new book with Sante’s oeuvre, is that she has found a way to elaborate on her major theme, her genuine conflict between two allegiances: Belgium and the US, the ruined, forgotten past and the modern present. Then there is the question of gender, about which Sante wrote so movingly in an essay for Vanity Fair after she started transitioning:

I once described myself as a creature made entirely of doubt, much of it self-doubt, but as soon as I made up my mind to come out, last February, I ceased doubting. That is to say, I experienced regular bouts of dysphoria, which in this context means intense recurring periods of self-doubt, self-hatred, and despair, which happen irregularly for varying lengths of time, typically (for me, by now) about two or three days a week. Yet paradoxically I had never before experienced such wholehearted conviction. Even in the throes of those bouts I felt an unaccountable bedrock of certainty.

In Nineteen Reservoirs, the primary tension is between her identities as a city dweller and a country person. Sante has seemingly channeled her three-fourths peasant self in identifying with the disenchanted viewpoint of her Catskills neighbors. She sympathizes with their frustration at the limits imposed on them in their own domain—no boating or swimming in these artificial lakes—without acknowledging the valid reasons for trying to keep the reservoirs pollution-free.

I must admit that, as a lifelong resident and celebrant of New York City, I feel guiltlessly happy enjoying the plentiful, tasty water provided by the state’s reservoir system. I am probably one of those people Sante speaks of with such disdain:

New York City continues to take its drinking water from those artificial lakes in mountain valleys, so inviting on a hot day in a region with no real lakes, albeit as taboo for swimming or boating as if they were meant for the gods alone. The ghosts of the drowned villages continue to haunt the popular imagination via roadside markers and twice-told tales…. Farms continue to fail, and farmers continue to die, and land and houses continue to be bought by city people who wouldn’t know their sheep-dip from their cream separator. New York, like other cities, is filled with people who have no idea where their water comes from and are only occasionally made aware that it is a precious and very finite resource that will become scarce again one day—perhaps quite soon. By then there will be no untapped mountain valleys to draw from.

Perhaps I should start to worry more. As Sante points out, every time the reservoirs have dipped below acceptable levels, as recently as last year, a hue and cry rises up to do something about conserving water; then the rains come and people forget about the threat. The reservoir system has held its ground, for the time being, and there are no predictions for when it might collapse. But Sante has performed a valuable service in raising hard questions about its mixed legacy.

This Issue

April 6, 2023

Becoming Enid Coleslaw

Putin’s Folly

Descriptions of a Struggle

-

*

A pity that Sante does not devote more space to Water Tunnels 1, 2, and 3, which connect the city to its upstate water supply. The first two were completed in 1917 and 1936; the third, begun in 1970 and still under construction, is the city’s largest infrastructure project in our time, and it gobbles up huge amounts of the municipal budget. But strictly speaking, these tunnels are not reservoirs. ↩