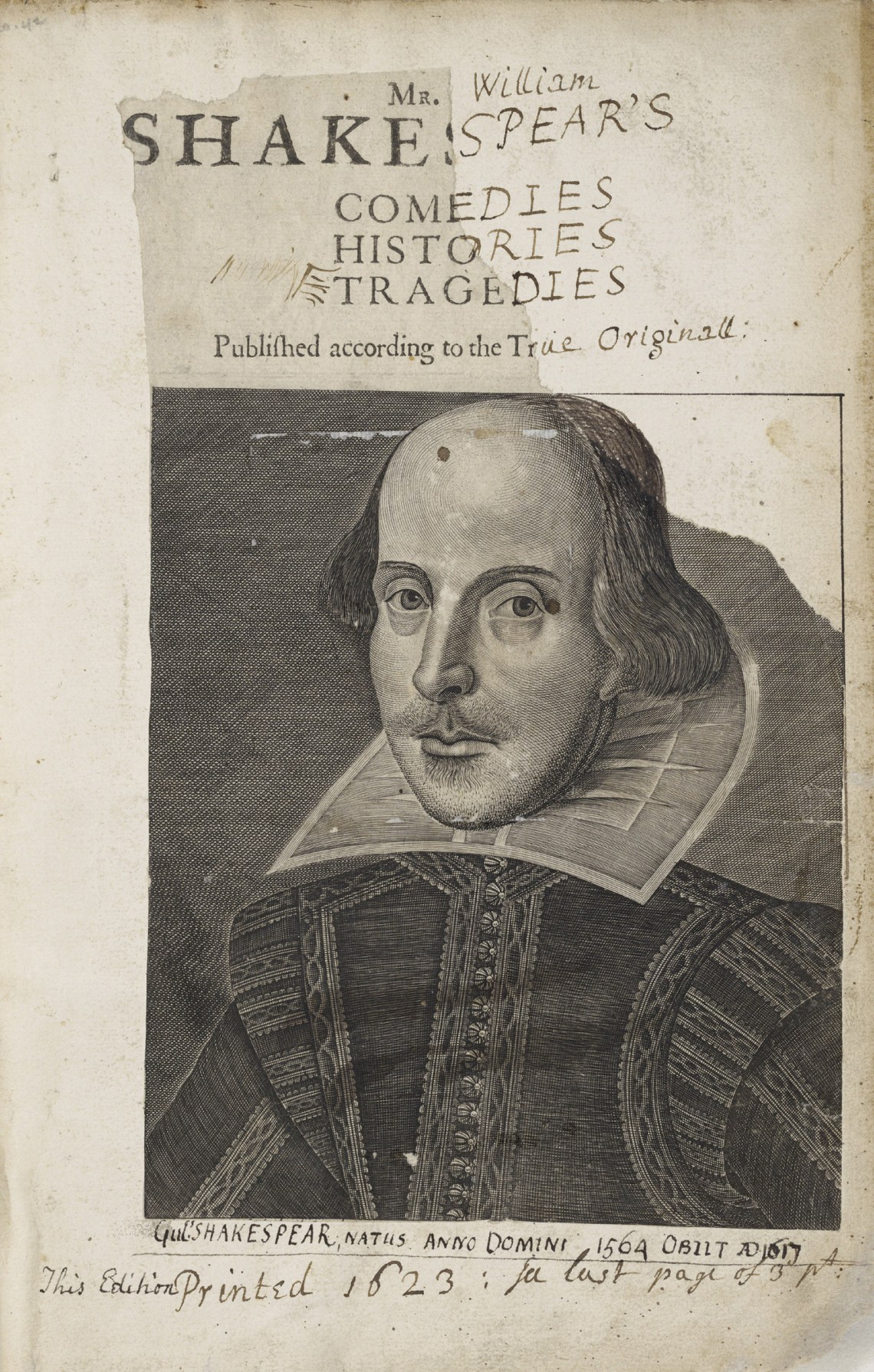

In late 1623, when the first printed copies of Mr. William Shakespeares Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies were presented to browsers in the bookstalls of St. Paul’s Churchyard, Sir Edward Dering bought two for a pound apiece—about $240 in today’s dollars, and as much as a London laborer might make in a year. (Dering also spent half a pound on a pair of stockings and bought a shilling’s worth of marmalade.) In exchange for his two pounds, Dering received a pair of thick, leather-bound volumes, printed in double columns and measuring about thirteen inches long and a bit over eight inches across. Unbound quarto editions of single plays typically sold for sixpence, a fortieth of the cost; in October 2020, when one of the 235 extant copies of the First Folio was auctioned off by Mills College, it went for nearly $10 million. The numbers are worth noting: there is no way that Dering or the publishers of the 1623 folio (a syndicate of five London printers and booksellers aided by members of Shakespeare’s former playing company, the King’s Men) could have foreseen the meteoric rise in Shakespeare’s cultural prestige or in the monetary value of their book, but the First Folio was intended from the start as a major—indeed, transformative—investment in Shakespeare as a literary and an economic property.

We call it the First Folio to distinguish it from the three subsequent folio editions of Shakespeare’s plays produced in the seventeenth century, the so-called Second, Third, and Fourth Folios. But the 1623 edition deserves the honorific in plenty of other respects. It is, to begin with, the first edition of Shakespeare in folio, a printing format typically reserved for classics or scholarly treatises. In 1616, when Shakespeare’s friend Ben Jonson arranged for his own poems and plays to be published in folio, he made a daring claim for the prestige of contemporary English literature—and for the place of stage plays in it. Shakespeare seems to have had no such ambition: the only published versions of his work with which we know he was personally involved, supplying a dedicatory epistle for each, were the quartos of two long narrative poems, Venus and Adonis (1593) and The Rape of Lucrece (1594), written when plague had shuttered the London theaters, depriving him of his regular income. Nonetheless, the 1623 edition of his plays is the first folio devoted exclusively to vernacular drama.

It is also the first full-scale collection of those plays, containing thirty-six of the thirty-eight (or, depending on whom you ask, thirty-nine) now generally accepted as Shakespeare’s, ten of them apparently revised or corrected from their earlier editions and eighteen—including The Comedy of Errors, As You Like It, Julius Caesar, The Winter’s Tale, and Macbeth—that had never appeared in print at all. They are, the title page vows, “Published according to the True Original Copies.” A prefatory epistle by John Heminges and Henry Condell, two of the players in the King’s Men, echoes that assurance, informing prospective buyers that “as where (before) you were abused with diverse stolne, and surreptitious copies, maimed, and deformed by the frauds and stealthes of injurious impostors,” Shakespeare’s plays “are now offer’d to your view cur’d, and perfect of their limbes; and all the rest, absolute in their numbers, as he conceived them.”

The First Folio wasn’t simply a fuller and ostensibly more faithful rendering of Shakespeare’s life’s work; it was a reframing of that work in overtly literary terms. The organization of the book makes its own argument for the value of its contents: the plays are arranged not chronologically (in order of composition, first performance, or initial publication) but formally, grouped into the ancient genres of comedy and tragedy and a third genre Shakespeare helped to pioneer, the English history play.* As the table of contents or “Catalogue” reveals, that scheme can be used to divide the playwright’s oeuvre into slightly lopsided thirds: fourteen comedies, ten histories, and eleven tragedies, in that order. (One play, Troilus and Cressida, isn’t listed in the Catalogue and seems to have been added late, wedged in between the last of the history plays and the first of the tragedies.) The result is a subtly but importantly different sense of what Shakespeare had fashioned: not simply a brilliant career in the theater, but a canon of vernacular drama.

The creation of that canon was Shakespeare’s achievement, but it was also the folio’s own. The makers of the 1623 volume supplied bibliographical coherence to what Margreta de Grazia has described in Shakespeare Verbatim (1991) as “a scattered and heterogeneous lot”: previously published quartos, unpublished manuscript sheets, actors’ parts, and theatrical promptbooks. Presiding over the newly assembled whole was another projected unity: the figure Ben Jonson hails in a long prefatory poem as “The AUTHOR, Mr. William Shakespeare.” Shakespeare’s name had only sometimes appeared on the quarto editions published while he was alive, and often in a smaller typeface than the name of the playing company or the publisher. The 1623 folio belongs unmistakably to him, and he to it: the title page features the now familiar engraving by Martin Droeshout, with its hooded eyes and sharply receding hairline, but a verse on the facing page, also by Jonson, urges the reader to look “Not on his Picture, but his Book.” For years theatergoers had enjoyed Shakespeare’s plays in performance and book buyers had consumed them in cheap print, but the 1623 folio imagines a new audience and a new readership for those plays, one for whom Shakespeare himself is the ultimate guarantor of literary value.

Advertisement

Without the First Folio, then, the surviving corpus of Shakespeare’s plays would be significantly smaller and distinctly less Shakespearean. A great deal would remain: we would still have Romeo and Juliet, Richard III, both parts of Henry IV, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, The Merchant of Venice, two distinct versions of Hamlet, and one (slightly altered) text of King Lear. We would almost certainly recognize Shakespeare as a, perhaps the, leading playwright of the early modern English stage. But our sense of his singular preeminence, universal scope, and undying relevance—our confidence that he, in Jonson’s famous formulation, “was not of an age but for all time!”—would likely be changed. The obviousness and ease with which Shakespeare sits at the pinnacle of literary culture owe a good deal to the collection, arrangement, and preservation of his brilliant plays in this book.

And yet, as Emma Smith argues in Shakespeare’s First Folio: Four Centuries of an Iconic Book, first published in 2016 and now reissued with a fresh preface, it is possible to overstate both the value and the significance of the 1623 Shakespeare folio. Indeed, Smith suggests, that is what we continually do, exaggerating its rarity, inflating its price, overlooking its textual and bibliographic weaknesses, fantasizing about its relation to Shakespeare himself, and forgetting or willfully obscuring the million accidents and historical contingencies that have facilitated its rise. Smith’s study is a trove of such accidents and contingencies, many belonging to the decades—indeed, more than a century—before the First Folio became an importantly old book, when it was simply an aging one.

In the most immediate and practical sense, as a commodity for those wishing to read Shakespeare’s plays, the First Folio was obsolete less than a decade after it was produced, supplanted by the Second Folio in 1632, the Third Folio in 1663–1664, and the Fourth Folio in 1685, each promising readers a corrected text, updated prefatory material, and—in the case of the Third Folio’s second issue, in 1664—seven additional plays, “never before Printed in Folio.” (Only one of those seven, Pericles, Prince of Tyre, is now regarded as “at least partly” Shakespearean.) For roughly a hundred years after its making, then, the First Folio steadily declined in value: the book for which Sir Edward Dering paid a pound in 1623 sold secondhand in the early seventeenth century for considerably less. Those who could afford to buy newer, better, and more comprehensive versions of Shakespeare mostly did.

The situation changed in the eighteenth century, as an emerging professional class of scholars, editors, and critics looked back to the early printed editions in search of an authentic Shakespearean text. The rise of textual editing restored the First Folio to prominence as a scholarly resource, being, in the editor Edward Capell’s words, “by far the most faultless of the editions in that form.” But the more closely eighteenth-century readers peered at the 1623 text, the more clearly its irregularities came into view: what Alexander Pope called its “arbitrary Additions, Expunctions, Transposition of scenes and lines, confusion of Characters and Persons, wrong application of Speeches, [and] corruptions of innumerable Passages.” Why were some plays divided into acts and scenes and others not? Why did the sequence of plays not conform to the order laid out in the table of contents? Why was the folio text of King Lear some two hundred lines (and an entire scene) shorter than the 1608 quarto? What, for that matter, was to be done about any of the thousands of instances in which the folio text differed from an earlier printed edition, in a word, a line, or an entire speech?

For his part, Capell deplored the First Folio’s textual and typographical flaws, saying, “What difference there is” between folio and quartos “is generally for the worse.” The great Shakespeare scholar Edmond Malone felt similarly, regarding the folio as—of necessity—“the only authentick edition” of the eighteen plays first printed in it but a decidedly second-rate source for the rest. Unsurprisingly, given these doubts, Capell and Malone both took a free hand with the folio text, emending whatever they deemed accidental, inaccurate, or nonauthorial in it.

Advertisement

But while editors like Capell and Malone worked to compensate for the First Folio’s textual defects, a new sense of its value emerged: not as a text to annotate, edit, or emend, or even as a book to read, but as an object to possess. By 1793 the Shakespeare scholar George Steevens called the 1623 folio “the most expensive single book in our language”; in the century that followed, the appetite for First Folios grew into what the self-described “Literary Man” and “Book Fancier” Percy Fitzgerald termed an “amiable mania.”

Fitzgerald wasn’t immune to the phenomenon, but he found it slightly baffling. “It is difficult to account for this craze, or indeed to define the element that is priced so highly,” he wrote in 1886. “It is not the text, for that is accessible in facsimile reprints; nor is it the scarcity, for there are other works far more rare, yet not so costly.” It could only, he concluded, be Shakespeare himself: “It seems really a compliment to the surpassing merit of the bard.” (This continues to be true, Smith shows: estimations of the folio’s rarity, desirability, and value outrun any rational accounting of how difficult it is to acquire.)

As Shakespeare’s cultural stature grew, so did the consequences of buying or selling a First Folio, which became an emblem of English identity and a bellwether of the nation’s fortunes. Sales of the First Folio at auction for fabulous sums made headlines in British newspapers throughout the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, but they also prompted grumbling about the encroaching ways of upstart Americans. As Sidney Lee noted when announcing the results of his 1902 Shakespeare census, which identified more than 150 First Folios, “The popular estimate of the volume’s rarity” was at considerable odds with “the precise testimony to its existing plenitude.” Nonetheless, Lee couldn’t help worrying about the folios’ westward drift:

Unlike our rich men the American millionaire is usually fired, when his bank balance grows substantial, with a holy zeal to acquire a copy of the First Folio. I honour this aspiration on the part of America’s plutocrats, although it is having the effect of draining this country of original copies of the volume.

“Folios follow money,” Smith writes, and as the market inflated over time, British owners frequently found themselves burdened by copies they couldn’t afford to keep and hated to be caught selling.

As Smith shows, the provenance of particular copies often maps suggestively onto the rise and fall and rise elsewhere of global wealth and power: from the libraries of aristocratic estates swollen by the profits of colonization, empire, and the Atlantic slave trade to the collections of robber barons and industrial magnates to the archives of universities and scholarly foundations. But Smith also tracks the paths of individual folios to some less predictable locales: to the home of an exceptionally diligent and probably Scottish seventeenth-century man named William Johnstoune, who seems to have set himself the task of reading and annotating every single play in it (his edition is now at Meisei University in Tokyo); to a pair of collections established by the British colonialist George Grey in New Zealand and South Africa; to the library of the actor-impresario David Garrick, whose organization of the 1769 Shakespeare Jubilee in Stratford-upon-Avon marks the birth of modern Bardolatry; and, in 1964, to the Vatican itself, where a First Folio once belonging to Charles Edward Flower, heir to a Stratford brewing fortune and founder of the town’s Shakespeare Memorial Theatre, was presented for a blessing from Pope John XXIII, then overseeing the Second Vatican Council, by an entourage of actors from the recently created Royal Shakespeare Company. (According to The New York Times, the pope initially thought the folio was a gift and had to be informed otherwise by the archbishop of Westminster.)

Some of the 235 First Folios that are known to have survived remain in private hands, but most are held by research institutions, and nearly a third (eighty-two in all) reside in a single place: the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, D.C., built to house the rare book collection of Henry Folger, early-twentieth-century chairman of Standard Oil. Such environments—tightly guarded, climate-controlled, and lavishly endowed—exert a powerfully determinative force on how, and by whom, the 1623 folio is studied and read. Or, rather, not read: for the overwhelming balance of interest in the folio today is invested not in the plays it contains (which are, after all, widely available to readers in cheaper, more accessible, more legible, better annotated, altogether more functional, and arguably more accurate versions, both in print and online) but in the book itself: its typography and page layout; its prefaces and paratexts; the paper, ink, thread, and leather from which it is made; and the wooden structures, human laborers, and tiny pieces of metal type that collaborated in its making.

These alignments, of Shakespeare’s plays with specialized academic environments and of the First Folio with the material circumstances of its production, were by no means inevitable. One of the most revealing stories Smith tells—a favorite among book historians—is that of the first First Folio ever to enter academic precincts: the copy sent to Oxford’s Bodleian Library in early 1624 from the London shop of Edward Blount, one of the five publishers who coproduced the book, as part of a standing arrangement between the Bodleian and the London Stationers’ Company to supply the university with certain kinds of newly published books.

It was something of a fluke that the Shakespeare folio made the cut. For when he founded the library at the start of the seventeenth century, Thomas Bodley had explicitly excluded playbooks from his plans, telling his librarian that “hardly one in forty” was worth the cost of keeping, and that even in that hypothetical one case, “the benefit thereof will nothing near countervail the harm that the scandal will bring unto the library, when it shall be given out that we stuff it full of baggage books.” “Baggage books” were small ones: relatively inexpensive volumes sold in pocket-size formats like quartos, octavos, and duodecimos. As Smith notes, it was thus likely the First Folio’s physical dimensions that made it acceptable to the Bodleian in 1624: “The size of the book was more important than its Shakespearean contents.”

Of course, the size of the 1623 folio was itself a mark of the publishers’ confidence in its value—why else invest in all that paper?—but that value was not yet in any way tethered to a sense of its particular or lasting importance. The 1623 edition of Shakespeare’s plays was a folio, which mattered, but it wasn’t yet a First Folio. And when it became one, the Bodleian lost any interest in keeping it: at some point before 1674, library records show, the 1623 folio was replaced by a copy of the 1664 Third Folio, with its seven additional plays. Why keep the outdated original instead of the upgraded new release?

Some 240 years later, in January 1905, the Bodleian First Folio resurfaced in the family library of an Oxford undergraduate, Gladwyn Turbutt, who brought it for authentication to the Bodleian staff. A power struggle ensued between the budget-minded head librarian Edward Nicholson, a scholarly sub-librarian named Falconer Madan, and the cash-strapped Turbutt family, who had received an offer of a staggering £3,000 for the book from an anonymous foreign collector—none other than Henry Folger. (At the time, the average price of a First Folio at auction was closer to £1,000.) In desperation, Nicholson embarked on a fund-raising campaign to make a counteroffer and, just before the deadline on March 31, 1906, with a last-minute assist of £200 from the Turbutts themselves, the target was reached. As Nicholson announced in the London Times, “The Shakespeare is saved.” The printed list of subscribers to the First Folio fund contains more than eight hundred names, with an average donation of three pounds each. Madan kept his own, splendidly petty handwritten list of “Persons who did not subscribe,” including the chancellor and vice-chancellor of the university, three regius professors, and various heads of college.

It’s a fun story, but the moral is hard to parse. For one thing, as Smith emphasizes, there was nothing illogical or irresponsible about the Bodleian’s decision to replace its 1623 folio with a copy of the 1664 folio: shelf space and money were in short supply, and the library routinely deaccessioned books and sold them to secondhand dealers. Indeed, the market for second and third editions, less risky and often more lucrative than the market for first editions, depended on buyers’ inclination to see later editions as both new and improved—as the Third Folio evidently was.

Similarly, the success of the collective effort to rescue the Bodleian First Folio from the clutches of that anonymous foreign collector in 1906 wasn’t a straightforwardly happy ending for the book. As Smith acknowledges, the Bodleian folio might have done better in the hands of someone like Folger. Lacking his bottomless reserves of cash, the Bodleian struggled to keep its recovered folio from deteriorating; by the end of the twentieth century, access to the book was barred even to scholars, and in 2012 a new fund-raising initiative was launched to create a digital facsimile. Like its twentieth-century forerunner, the 2012 campaign to rescue the Bodleian folio was couched in a rhetoric of urgency that both exaggerated the book’s emblematic importance—even within the Bodleian itself, which in 1821 had acquired another copy of the First Folio from the estate of Edmond Malone—and belied its relatively robust rate of preservation. High-quality digital facsimiles are no rarity, either: in 2012 there were already a dozen available online.

The conviction that the First Folio, which matters so greatly to us, must have mattered in the same way all along can make it hard to see the book for what it is and was. The distortions of Bardolatry are, unfortunately, everywhere apparent in Chris Laoutaris’s Shakespeare’s Book: The Story Behind the First Folio and the Making of Shakespeare—starting with the title, which implies a personal, possessive relation between Shakespeare and the 1623 folio that is, on the basis of the surviving evidence and the fact that Shakespeare was dead seven years before it was made, nearly impossible to sustain.

The resulting argument is both monomaniacal—everything comes back to Shakespeare in the end—and scattered. For it isn’t one story Laoutaris has to tell but a handful of them, each championing a slightly different, sometimes conflicting set of theories about how the First Folio was made and what it was meant to be. Was it, for instance, a heartfelt if slightly belated expression of grief and affection on the part of Shakespeare’s theatrical fellows, “devote[d]…to the commemoration of their late friend”? Or was it, perhaps, a calculated attempt to head off a “devilish scheme” by a dodgy publisher and a father–son pair of printers to produce a fraudulent and unauthorized collection of Shakespearean plays—a so-called False Folio? Or a cautious, densely coded effort to play both sides of an unfolding political uproar over Anglo-Spanish relations and the line of royal succession? Or an extension of Shakespeare’s own alleged efforts to affiliate himself with a network of Oxford-educated poets, wits, and men-about-town—even, perhaps, to secure for himself “his legacy in print”?

The evidence for some of these narratives is distinctly more robust than for others, and Laoutaris is not good at helping readers tell the difference—or at flagging the moments when his scholarly sources and archival evidence give way to fabulation. (He has a habit of using “must” and “would” where a more responsible writer would put “might” and “could.”) More careful, coherent, and convincing by far is Ben Higgins’s excellent Shakespeare’s Syndicate: The First Folio, Its Publishers, and the Early Modern Book Trade, which suggests how much the Shakespeare folio might have to teach us if we don’t think of it as Shakespeare’s alone.

Shakespeare’s Syndicate is, as Higgins puts it, “an extended close reading” of what may be the least-read lines in the First Folio: the publisher’s imprint at the bottom of the title page—“Printed by Isaac Jaggard, and Ed. Blount. 1623”—and the colophon at the very end—“Printed at the Charges of W. Jaggard, Ed. Blount, J. Smithweeke, and W. Aspley, 1623.” William and Isaac Jaggard were the printers of the 1623 folio; Edward Blount was the lead publisher and primary investor; John Smethwick and William Aspley were secondary publishers and investors, likely brought into the syndicate to secure the rights to the six Shakespeare plays they owned between them. Like Laoutaris, Higgins has more than one story to tell, but in his book multiplicity is a virtue: focusing each chapter on a different member of the folio syndicate, Higgins reveals how many possible motives and rationales for the enterprise might have coexisted, without necessarily needing to cohere around the memory or intentions of Shakespeare himself.

For Blount, the folio was part of an ongoing effort to create both a market and a taste for vernacular literature. Over the course of his lengthy career he published poems and plays by Christopher Marlowe, John Lyly, Samuel Daniel, and Ben Jonson, along with the first English translations of Montaigne and Cervantes; as Higgins argues, it’s less accurate to say that the folio establishes Blount as a literary publisher than that Blount made Shakespeare a literary author. The father–son printers William and Isaac Jaggard share a crucial chapter between them: the story of their relationship to the First Folio has long been the most vexed and vexing piece of the history of its making, thanks to their near-simultaneous involvement with an apparently unauthorized rival production, a collection of ten quartos (eight by Shakespeare and the other two evidently attributed to him) assembled in 1619 in collaboration with the publisher Thomas Pavier.

The discovery of the Jaggard-Pavier quartos in the early part of the twentieth century by the scholar W.W. Greg galvanized the emerging field of textual bibliography: as Greg revealed, the dates on a number of the title pages had been faked, so what looked like a bound collection of remaindered plays was in fact a fraudulent collection of newly printed plays. And as Zachary Lesser has shown in his 2021 book Ghosts, Holes, Rips and Scrapes: Shakespeare in 1619, Bibliography in the Longue Durée—a tour de force of revisionary sleuthing that also manages to mount a thoughtful critique of our appetite for revisionary sleuthing—that discovery infected the field with a heady, often misleading atmosphere of conspiracy, with the Jaggards cast as conspirators in chief. Higgins takes a less censorious view, arguing that their involvement in both the 1619 quartos and the 1623 folio testifies mainly to their persistent—and, in retrospect, prescient—faith in Shakespeare’s marketability: if we seek a seventeenth-century precursor to the idea of Shakespeare as a sound financial investment, the Jaggard printshop is the place to look.

William Aspley’s interest in Shakespeare was, by contrast, distinctly minor: though he published two of his plays in quarto, Higgins argues that Aspley’s chief interest, financially and otherwise, was in the larger and more profitable market for religious books. That the 1623 folio of Shakespeare’s Comedies, Histories, & Tragedies would, in the long run, come to seem vastly more important than Aspley’s 1622 folio of The Workes of John Boys Doctor in Divinitie would have struck Aspley as unlikely in the extreme.

As for John Smethwick, although he owned more of the playwright’s titles than anyone else in the syndicate, having the rights to four plays in quarto, Higgins argues that his real value to the group was geographic: because his shop was in St. Dunstan’s Courtyard, west of St. Paul’s, he helped tap an audience for the First Folio among the university students and young lawyers at the Inns of Court—an audience that seems to have kept the Shakespeare brand afloat after 1623, when St. Paul’s book buyers appear to have lost interest. Indeed, Smethwick went on to publish seven additional single-play editions of Shakespeare and took the lead in the production of the 1632 Second Folio; St. Dunstan’s became the center of a decade-long Shakespeare revival. But the revival didn’t last. Far from inciting a sustained appreciation for Shakespeare’s art, the flurry of single-play quartos that appeared alongside the First and Second Folios in the 1620s and 1630s “heralded a difficult phase of their author’s literary life: after the initial flush of popularity had faded but before the redemption of posterity and canonicity.”

What would Shakespeare have made of his life-beyond-life in print? In the final chapter of Shakespeare’s Book, Laoutaris sketches a dizzying web of connections between the playwright and a publisher named John Robinson, who might—though we have no evidence of this—be the same John Robinson who rented a London flat from Shakespeare in 1616, a possibility Laoutaris takes as a sign that Shakespeare might have been planning a collected edition of his works before he died. Maybe he was. But if we want a glimpse of what he thought about the power (and the perils) of bibliolatry, we’d do better to read the First Folio itself.

The Tempest is likely one of the last plays Shakespeare wrote, but it appears first—and for the first time—in the 1623 folio. At the center of the play is a book (or a small collection of books; it isn’t clear which) belonging to the magician Prospero. Caliban’s plot to strip Prospero of his occult powers and seize control of the unnamed island where he has established his rule runs aground on a single unheeded piece of advice, the enslaved creature’s counsel to the pair of shipwrecked servingmen he enlists in his conspiracy: “Remember/First to possess his books, for without them/He’s but a sot, as I am.”

Unfortunately for Caliban, the servingmen are drunk and easily distracted: arriving in Prospero’s cell, they make a beeline for his royal robes and are swiftly overcome by an army of invisible spirits. Prospero’s books—the cherished remains of a once grand library, amassed when he was Duke of Milan, before his treacherous younger brother, Antonio, deposed and banished him—remain in the magician’s possession until the play’s final act, when he voluntarily relinquishes them.

Or, rather, voluntarily relinquishes it, for the magical library now seems to have dwindled to a single, irreplaceable book. Having brought his brother to justice, reclaimed his dukedom, matched his teenage daughter, Miranda, with the son of the King of Naples, and foiled Caliban’s plotting, Prospero declares:

But this rough magic

I here abjure, and when I have required

Some heavenly music, which even now I do,

To work mine end upon their senses that

This airy charm is for, I’ll break my staff,

Bury it certain fathoms in the earth,

And deeper than did ever plummet sound

I’ll drown my book.

It’s a famous speech, culminating in what looks like a gesture of wise self-limitation, a willing descent from magical omnipotence to the merely human world. (Nineteenth-century Shakespeareans eager to construct a biography for the bard read it as his farewell to the London theater, though in fact Shakespeare collaborated on at least two additional plays before his retirement to Stratford-upon-Avon.)

From another vantage point, however, the drowning of Prospero’s book isn’t a constraint on his power but a necessary step to regaining it. As he admits to Miranda in the play’s opening act, the loss of his dukedom to Antonio was a direct consequence of his absorption in books:

Those being all my study,

The government I cast upon my brother

And to my state grew stranger, being transported

And rapt in secret studies.

Over time, unsurprisingly, Antonio comes to resent the arrangement—having assumed all the responsibilities of the role, “he did believe/He was indeed the Duke”—while Prospero seems almost to crave his own deposition: “Me, poor man, my library/Was dukedom large enough.” In this version of events, he is not the possessor of a magical library but a man dangerously possessed by one; the hard lesson of his life—and the deep irony of Caliban’s planned revenge—is that books can be distractions, too. What is the right amount, and the right kind, of attention to pay to a book? It’s a hard question to answer in The Tempest, and a hard question to ask of the volume to which we owe our acquaintance with that play, and so much more.

-

*

A fourth category, “romances,” now applied to a handful of tragicomic late plays, emerged in the late nineteenth century. ↩