When fire broke out in the royal palace in Munich in 1729, it destroyed a painting of the Assumption and Coronation of the Virgin made by Albrecht Dürer between 1507 and 1509. This is the “lost masterpiece” of Ulinka Rublack’s title. It was the central panel of the Heller altarpiece, commissioned for the Dominican church in Frankfurt by the merchant Jakob Heller, and the acrimonious exchange over it between Dürer and his patron serves, Rublack explains, as “a lens through which to view the new relationship developing between art, collecting, and commerce in Europe” in the sixteenth and first half of the seventeenth centuries. To illustrate this relationship, she structures her exhaustive study around three figures: Heller, the banker Hans Fugger, and the international art agent—and probable spy—Philipp Hainhofer. Her account raises questions about the meaning of “value” in relation to works of art and artifacts, considering not only money and materials but also the power of such works to embody philosophical ideas, cultural movements, and changing fashions.

Duke Maximilian I of Bavaria had whisked Dürer’s panel off to his private collection in Munich in 1614, just over a century after it was completed, arranging with the Dominicans for a copy to replace it. This copy is now in the Historisches Museum in Frankfurt, and although it lacks Dürer’s skilled brushwork and glorious colors, it allows us to see his design and in particular one daring, even shocking, detail. Just to the left of center Dürer painted his own portrait: an isolated figure in a recognizably German landscape, poised between the apostles looking up in awe and the Madonna floating above. He holds a board with “credits larger than a shop sign” declaring that he, Albrecht Dürer, had created this picture, ending with a large version of his monogram, “AD.”

Dürer was known for his self-portraits, which asserted his status as an artist—most famously for the portrait of 1500, in which he adopts the traditional full-frontal pose used in paintings of Christ, with the blond highlights of his long, curled hair reflecting the gold of his monogram. Dürer is present in countless engravings and drawings, but in more prestigious commissions he usually appears on a side panel, in the background or as part of a group, not isolated and eye-catching as in the altarpiece. Furthermore, in it he is dressed not as an artist but as a fashionable man of rank, with a startling blue coat the color of the Virgin’s robe. His black bonnet, long sword, rings, and bracelet all make him “stand out aesthetically and bolster his claim that he and his fellow artists were superior to common folk and craftsmen.”

Rublack describes this blatant intervention as “Dürer’s Revenge,” the last gesture in the fierce dispute between artist and patron. The nub of the argument was money: Dürer pushed his fee up; Heller refused to pay; Dürer argued that the demands of time and the cost of pigments justified the price; Heller objected furiously to the delay while still insisting on “good oil colours, that stay fast and clear to delight those who will admire my altar.”

To Dürer, it was “my” altar as much as Heller’s. The son of a master goldsmith in Nuremberg, he had been apprenticed at fifteen to the artist Michael Wolgemut. In 1495, having just returned from his first trip to Italy, he opened his own workshop and was soon acclaimed for his woodcuts, notably the Apocalypse series of 1498; for elaborate and fantastical engravings such as The Sea Monster (1498) and Nemesis (1501–1502); and for his atmospheric landscapes and paintings of Madonnas. Inspired by his time in Venice, he was determined to show himself supreme as a painter, to become the “German Apelles.” Proudly he told Heller, “What I agreed to was to paint for you something that not many men can.” It would, he claimed, enthrall people five hundred years hence.

Dürer managed to increase the fee slightly, but as far as monetary value was concerned, Heller won. Bruised and angry, Dürer painted no more altarpieces, returning to more commercially viable work. But in the course of the dispute, Rublack argues, he fought a historic battle that proposed a new way of bargaining and asserting the worth of artistic work, one that requested “fair compensation for the rarity of what he produced through a great investment of time, diligence, material worth, knowledge, experiment, and emotion.”

Rublack, a professor of history at the University of Cambridge recognized internationally for her studies of early modern Europe and Reformation Germany, places Dürer’s Lost Masterpiece firmly in the strand of scholarship focused on the history of material culture. Her aim, she writes, is to recover “practices, personal relationships, political networks, market relations and the demands and potential of different kinds of matter and objects themselves” and to demonstrate how commerce acts as a “cultural force.” This approach has given rise to rich studies over the past thirty years or so, from Lisa Jardine’s Worldly Goods: A New History of the Renaissance (1996) to Anne Goldgar’s Tulipmania (2008) and James Delbourgo’s Collecting the World (2017). In addition to an award-winning study of Johannes Kepler’s efforts to exonerate his mother while she was on trial for witchcraft, Rublack’s books have often investigated cultural identity in Renaissance Europe, and she coedited Materialized Identities in Early Modern Culture, 1450–1750 (2021).*

Advertisement

She relates Dürer’s time in Italy, for example, and his exchanges with his friends Willibald Pirckheimer and canon Lorenz Behaim, not only to their interest in humanism and classical learning but to contemporary ideas of sensual and sexual responses as part of a vivid physical response to the natural world. This connects with the physicality of Dürer’s painting, his use of fingers for stippling and the balls of his hands to achieve atmospheric effects. But Dürer also wished to convert time itself into the money due to him: the time it takes to make preparatory drawings, to apply layers of underpainting, to wait for different colors to dry at different rates. Color, too, has different forms of value. “Colours derived from minerals, earths, shells, or residues of fabric dye,” writes Rublack.

Much knowledge lay in choosing and processing these judiciously to unlock the beauty and secrets which lay hidden inside these types of matter. Dürer needs to be rematerialized, and the Heller correspondence enables us to do this.

A brilliant discussion of pigments and color links artistic endeavor both to the growing global trade routes—sourcing ochre from Armenia and ultramarine from Afghanistan—and to contemporary interests in chemistry, metallurgy, and alchemy. The discussion of alchemy leads in turn to a consideration of beliefs that endow matter with transcendent meaning, such as the Neoplatonist Marsilio Ficino’s conviction that color, including wearing clothes of “blazing yellows, pure golds, and lighter purple,” could have a transformative power, helping a man’s spirit to become Apollonian, or “solar.” The dazzling colors of Dürer’s Madonna could thus enable the artist to become “a healer of souls” and perhaps, Rublack suggests, to offer a personal solace, too. Both Dürer and Heller were preoccupied with the status of their family, yet both their marriages were childless.

It is disconcerting, given the title and the engrossing opening chapters, to find that Dürer is completely absent from the central section of the book. Here Rublack turns to the merchant and banker Hans Fugger, whose thousands of letters contain only one mention of the artist. In the vogue for collecting in the decades after Dürer’s death, painting was of minor importance. The criteria of value changed; the sense of mystery inherent in matter gave way to a hunt for the “curious”—the rare and strange. Dürer understood the allure of this pursuit. When he was in Venice, his friend Pirckheimer sent him constant requests for books, rings, Turkish carpets, and “crane feathers to fashionably decorate his bonnet.”

A decade or so later, in Brussels and Antwerp, Dürer marveled at the astonishing feathers from the New World and the Chinese porcelain, coconuts, and coral given him by Portuguese traders. This was only the start of the passion for collecting. While it was conceived as a way to gain knowledge of the natural world, other cultures, and new technological developments and medicines, the deeper significance for patrons was the way that collections and museums of “Useful Wonder” magnified their status and power. The atmosphere was altogether more worldly.

As the craze grew, cabinets of curiosities ranged from elaborately made chests to entire suites of rooms and specially built galleries. In the quest for “curious” objects merchants forged bonds with aristocratic courts, and the mounting debts of nobles like the Wittelsbach dukes of Bavaria and the Habsburg Holy Roman Emperors tightened those bonds still further. For their part, knowing the debts were unlikely to be repaid, merchants built hopes of reward on ennoblement or aristocratic marriages and on their own reputation as patrons of culture.

The situation was complicated still further for Fugger because of a bitter split within his family. The Fuggers had made their fortune initially from mining and textiles in Augsburg, and then from loans to local rulers, the papacy, and the Habsburgs. But by 1560 the firm was almost crippled by the Habsburgs’ outstanding debts, and after the leading member, Hans Jakob, filed for bankruptcy and left to work for Albrecht V of Bavaria in Munich, the firm was run by his cousins, the scholarly Marx and the practical Hans—Rublack’s focus of interest. Hans shrewdly married into the imperial nobility and built on the connections of his wife, Elisabeth. His tireless work for Albrecht’s son Prince Wilhelm was partly insurance, as Wilhelm’s mounting indebtedness ensured his future protection against the threat of paying their hated cousin’s debts.

Advertisement

Hans Fugger’s interest was in building, decoration, and display. The huge frescoes for the vast reception rooms, designed to hold his collections, were his only commitment to innovative painting. For these he employed the artist Friedrich Sustris, who had trained under Giorgio Vasari while decorating the Medicis’ Palazzo Vecchio in Florence—the Medicis were clients of the Fuggers, building up huge debts, but also an inspiration as models of Italian taste. The discussion of taste leads to Rublack’ s emphasis on personal display, from top to toe. Fashionable shoes and hosiery, she writes, constitute a “visual act which displayed new materials and technologies.” In one instance, demand surged for colored stockings woven from fine wool or silk, with new dye tones and intricate, superfine stitching.

Children as well as adults sweated in workshops across Italy to produce them. Cosimo de’ Medici owned fifty pairs of silk stockings, black and colored, and his son Francesco sixty-eight. Like a Renaissance Imelda Marcos, Cosimo also owned at least sixty pairs of boots. And while German courts and merchants were determined to equal the Italians, purchase was not easy: indeed, it sounds worse than buying clothes online. Sometimes the eagerly awaited stockings or shoes simply did not fit or look elegant enough. Fugger, minutely concerned with new patterns, the suppleness of the leather, and the skill of the workers, often had to send his orders all over again.

Fugger’s purchases derived added meaning: his Italian- and Spanish-style footwear proclaimed his ties to the Catholic imperial nobility as well as his wide trade links. At all levels of acquisition, political allegiances and collecting overlapped. Gifts between rulers were significant, and they sometimes came with instructions. In 1573 Philip II of Spain, viewing the Wittelsbachs as potential allies in Habsburg Germany, sent boxes filled with perfumed gloves and silks, as well as pâtisseries for Albrecht and Wilhelm (but not, it was stated, for the ladies):

The scene of a Bavarian duke and his son unpacking a box filled with gloves and sweets encapsulates a German Renaissance we have lost sight of—a cultural movement filled with excitement about subtlety in food and decorative arts in which items of dress, sugary concoctions, or materials such as the finest fibres and leather played a key part.

We may marvel, but there is something repellent about this greedy, eager, and determinedly conspicuous consumption. Grand collecting came at the cost of unpaid craftspeople and overburdened local taxpayers. Throughout the century unease at inequity mingled with Protestant unrest. In the early 1520s manifestos called “for an equal society based on common property and and brotherly love.” Sixty years later, in an inquiry into the Protestant uprising in Augsburg in 1584, the entire Fugger family was attacked for evasion of taxes and for buying up and demolishing houses to create pleasure gardens, which made it harder for the poor to find places to live.

The degree of exploitation in the celebrated global trade and the horrors of colonial expansion to come also surface in passing glimpses: in Dürer’s fascination with the “proportions and beauty” of African slaves who served him at an Antwerp dinner, and in Fugger’s lavish wall coverings. Production of these stylish decorations was aided by the influx of “Spanish” leather from the Hispanic Caribbean “where the decimation of the local population provided colonists with large pastures on which to graze the cattle.”

Fugger’s work for Wilhelm and his wife, Renata of Lorraine, proved exhausting and extremely costly. He was responsible for sourcing and paying for everything from rare rabbits, women’s hats adorned with gold and pearls, and “Italian armour, diamonds and meercats” carried over the Alps to plants for her gardens. The culmination of fifteen avid years of purchasing was the Munich cabinet of curiosities, a grand Renaissance building that was almost completed when Wilhelm became duke in 1579. It contained artifacts and natural objects from every continent. While demonstrating Wilhelm’s power and learning, it was also, Rublack says, designed “to stimulate entrepreneurial interests in global trade.” Yet while Wilhelm continued to accumulate new treasures, his debts finally drove him to near bankruptcy, and in 1594—the year of Fugger’s death—he appointed his son Maximilian, then aged nineteen, as coruler, then handed power over to him completely in 1598.

Maximilian I and his peers had new priorities. In the decades before the 1580s rulers and merchants—in the Dutch Republic, Hungary, and Germany—had begun to seek out old master paintings again and to commission copies of altarpieces, so recently the target of iconoclasts. Art lovers began to negotiate directly with convents, monasteries, and churches, offering copies in exchange for originals. Northern artists were particularly in demand, and when the Habsburg emperor Rudolf II planned a separate gallery to stand alongside his cabinet of curiosities in Prague, Dürer was at the top of his list. In 1585 he bought Dürer’s Landauer Altarpiece from Nuremberg, turning it, Rublack comments, from a functioning altar “into a piece of art devoid of any religious context.” In the same spirit, he acquired a second Dürer altarpiece, Feast of the Rose Garlands, from Venice. The publication of Karel van Mander’s Schilder-Boeck (Lives of the Northern Painters) in 1604 intensified the interest in Flemish, Dutch, and German painters, which was not, Rublack points out, a divergence from the hunt for luxuries but part of the same movement.

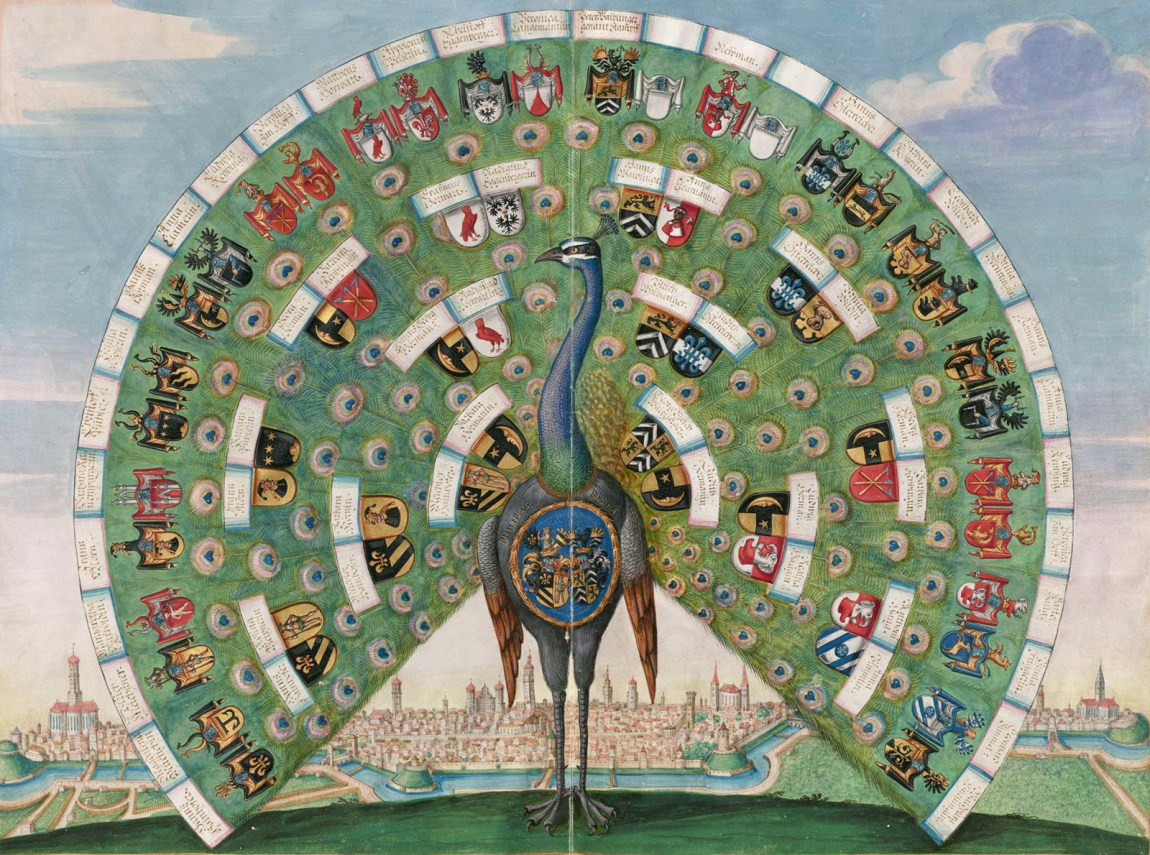

The star broker in this new age was Philipp Hainhofer, from a family of textile and copper merchants from Augsburg. Educated in Padua and Siena, well traveled, speaking several languages, and building profitable connections at the annual Frankfurt fairs, Hainhofer worked with teams of craftsmen to supply superb cabinets of curiosities to patrons from Poland to Italy and Britain, driving up prices through their rivalry for precious items. Networking was essential, as demonstrated by Hainhofer’s Album Amicorum. This lavish “friendship book” contained the autographs of rulers and patrons, including the Emperor Rudolf, Christian IV of Denmark, Cosimo de’ Medici, and many more, their entries illustrated by leading artists. It became a must-see treasure for potential customers, who negotiated keenly for their own page.

Rublack gives an unparalleled account of Hainhofer’s career, drawn from his extensive unpublished papers and tracing his varied and intricate dealings as a self-styled liefhebber, or art lover—a term widely adopted in the Netherlands. The art lovers’ shared mission, in theory, was “to spread civilization and concord in an age of confessional tension.” In practice, despite the rhetoric of openness and connection, it was less a movement connecting aesthetes across distances and religious divides than a drive by merchants to exploit the competition between patrons. To Wilhelm, Hainhofer offered a vast array of goods, from Jodocus Hondius’s beautifully illustrated and expanded edition of Mercator’s Atlas—a guide to where treasured rarities came from—to “Indian” feathers, skirts, rings, and bowls from the East Indies and “a stuffed rat from Lithuania that warded off insects from damaging clothes.”

Suavely, Hainhofer managed to please both Catholic and Protestant patrons. As well as cleverly balancing the demands of, and mediating between, the Catholic Wilhelm and his other principal patron, the Lutheran Philipp II of Pomerania, he won the trust of Maximilian I, who was ruthlessly determined to recatholicize his region. Exchanging sensitive political information as well as sourcing goods, Hainhofer gradually acquired diplomatic status and in the process became a secret informant to different courts, including that of France.

In the hunt for works by Dürer, Hainhofer had no qualms about playing one patron against the other. He was not, however, involved in the hard negotiations that led to Maximilian I’s obtaining the Heller altarpiece panel in 1614. Maximilian sought Dürer’s works principally for their rarity but also because of the artist’s “industriousness,” a virtue he prized greatly. He hung the painting in the gallery connected to his bedchamber, and he might, it is suggested, have valued it also for its content, as “worship of the Virgin Mary nearly equalled a ‘state cult’ under his rule.” The criteria of value had shifted again. In a time of religious tension and growing hostilities an altarpiece could be freighted with confessional significance: paintings could become the flags of the Counter-Reformation.

Collecting luxuries continued during the Thirty Years’ War, which began in 1618. Opposing states “enrich[ed] their collections through plunder,” and profiteers moved in to scoop up the luxuries that impoverished owners were forced to sell. These included the Earl of Arundel, who descended on war-torn Germany in 1636, seeking out agents and collectors. Arundel had a Catholic upbringing and sympathies that would have made him revere a painting of the Virgin (and he did acquire one by Dürer), but his interest in German art was wider; he returned to England laden with Holbeins and two other paintings by Dürer. As Rublack notes pertinently:

The way in which art was obtained, through theft, looting, imperial scramble, or bargains, left no mark once objects had entered collections. Owners of these collections obliterated these histories by providing a refined setting in a new location.

Arundel’s methods were unscrupulous. He moved swiftly, for example, after the Amsterdam market crashed when the price of tulip bulbs collapsed, leaving connoisseurs ruined and paintings and prints going cheap. In Germany, it was the religious wars, rather than any financial crash, that took their toll on lives and fortunes. Hainhofer’s international art agency was reduced to the verge of bankruptcy. In 1645 he wrote, “The vicissitudes of the times have sadly robbed me of all my things and rarities, and what I have left is pawned.” By the time he died two years later, a year before the Peace of Westphalia, the wealth of Augsburg’s merchants was reduced to roughly a sixth of pre-war levels, and its population to less than half. The great phase of merchants’ involvement with collecting was over.

Dürer’s Lost Masterpiece, which analyzes that era minutely, is the product of over fifteen years of research in archives and collections. Reading it, I sometimes wanted to get my head above the dense accumulation of detail and to find places where Rublack might have set her account against a broader picture of society or clarified exactly how her argument applied. Yet it is precisely that amassing and marshaling of detail that makes her book such an outstanding portrayal of the merchant as a creative agent and a remarkable contribution to the history of the European art market as a whole. Perhaps, too, it might jolt us into a keener interrogation of collecting and the art market today, and a questioning of our own attitudes toward the vexed value of art.

-

*

Dressing Up: Cultural Identity in Renaissance Europe (Oxford University Press, 2010); The Astronomer and the Witch: Johannes Kepler’s Fight for His Mother (Oxford University Press, 2015). ↩