In the summer of 2017, eleven FBI agents searched a small house in a run-down neighborhood in Augusta, Georgia, where a twenty-five-year-old NSA contractor named Reality Winner lived alone with a cat and a foster dog, neither of whom liked men. She’d mostly furnished the rental with exercise equipment, but she’d also hung up framed posters of the Beatles and Billy Joel, alongside pencil sketches of Gandhi and Martin Luther King Jr. When she wasn’t working out, which she did obsessively, Winner enjoyed painting. Among her favorite subjects were Nelson Mandela, Jesus Christ, and herself.

A few days after the search, during a bond hearing, a prosecutor claimed that what the agents found inside the house was “downright frightening.” Under Winner’s bed, which was draped in a Pokémon blanket, were a Glock and a shotgun. They also gathered one tablet, two laptops, and four cell phones, as well as several notebooks in which she’d scrawled the names of various Islamic extremists. On one page, among the details of her dental insurance policy, she’d written, “I want to burn the White House down.”

On her computer, the agents discovered, Winner had googled the Twitter account of a Taliban spokesperson and flights to Jordan. She’d looked up how to get a work visa in Afghanistan, how to change SIM cards, and how to download Tor, the anonymizing browser. The prosecutor highlighted that Winner had gone to Mexico more than once; more recently, she’d visited Belize, alone, for three days. “Nothing criminal about that, Your Honor,” the prosecutor said, “but it seems odd to spend the kind of money necessary for a trip all the way to Central America.”

At least one of Winner’s lawyers thought this line of reasoning was “dumb.” Surely, the judge would appreciate that his client’s pyromaniacal musings had been followed by the words “ha, ha.” That she had wanted to live in Afghanistan to work with refugees. That she had traveled to Belize to see the Mayan ruins after the death of her father. That her father had taken her to Mexico as a kid partly because it was cheaper to get her braces fixed across the border. That she might have been curious about the people her employers were determined to kill. That there was, as the prosecutor had put it, “nothing criminal” about any of that.

Winner was the latest millennial to be charged under the Espionage Act, the controversial World War I–era law, revived during the Obama administration, that punishes the unauthorized release of national security information. Yet compared with the troves of data released by Edward Snowden and Chelsea Manning, which revealed just how prodigious (and indiscriminate) the government’s data collection had become, Winner’s subterfuge was clumsy and contained. It frustrated her that the post-2016 election coverage on Fox News, which blared on the TVs at the NSA building where she worked, was belittling the idea of foreign interference. One day, while browsing her computer’s classified cache, she printed out a five-page document that detailed Russian attempts to tamper with American voting machine software, smuggled it out of the building in her pantyhose, and mailed it to the PO box of The Intercept, an online news outlet (where I’ve worked as a contributing writer).

When a reporter there asked the NSA to authenticate the document, he shared it with the agency without consulting the newsroom’s formidable security team and without removing identifying marks. He also let slip to an intelligence source that the envelope had been postmarked from Georgia. It does not excuse these sloppy missteps to note that Winner would likely have been apprehended in due time: only six other people had printed the document, according to an FBI affidavit, and only one of them had ever e-mailed the outlet from a work computer (asking for a transcript of a podcast that discussed Russia). By the time The Intercept published the scoop on June 5, 2017, its anonymous source was already behind bars.

Kerry Howley, a staff writer at New York magazine, takes up Winner’s ill-fated case in her mordant and absorbing book Bottoms Up and the Devil Laughs, which she has described as a nonfiction thriller about the surveillance state. Winner was an agent of this state before she became one of its targets. She spent her early twenties in the air force, serving as an intelligence specialist and linguist in drone operations that, as Howley writes, “swept people from the lands she oversaw.” After burning out on the targeted killing program, she used her security clearance (and fluent Farsi, Dari, and Pashto) to obtain a less stressful job as a military contractor, translating documents related to Iran’s aerospace program. (The office culture was such that one of Winner’s colleagues had time to mold Tootsie Rolls into little sculptures resembling the poop emoji, which she deposited at random desks.)

Advertisement

The Espionage Act is broadly worded: it prohibits the unauthorized possession or sharing of “information related to the national defense,” regardless of whether the information was leaked to serve the public interest. It is already difficult for defendants to fight charges brought against them under the act; it’s essentially impossible when the leaker herself has confessed to the alleged crime. As the FBI agents ransacked Winner’s home, they good-copped her into admitting, on tape, that she’d made a mistake. This left Winner’s lawyers with a limited line of defense: to prove that the secret she’d leaked was known to at least some of the millions of other Americans with security clearances, and therefore not a matter of national defense. But to make that argument they would have had to draw on information about the architecture of state secrets that was, by definition, classified.

Howley pays particular attention to how the Department of Justice used this catch-22 to its advantage as it picked the most incriminating fragments of Winner’s biography to serve its story. At the bond hearing it was suggested that Winner had “a fractured life or a fractured personality.” Winner’s friends and family knew the side of her that “teaches yoga and loves dogs and is nice to be around,” the prosecutor told the judge, “but as they’ve admitted, they have no insight into her work life, into her interest as it pertains to travel to the Middle East.” The prosecutor did not acknowledge that if Winner had shared her work life with them, she would have been breaking the law.

Deemed a flight risk (her holiday in Belize was considered a red flag), Winner was denied bond. On one of the many calls she made to her sister, Brittany, from jail in Georgia, she lamented not thinking about the consequences of a “stupid decision.” When Brittany joked that being pretty, white, and blond should earn her some sympathy, Winner replied that she would keep her voice small and her hair in braids. A tape of this conversation was obtained by the prosecutor, who, ignoring its droll tone, submitted it as further evidence of the defendant’s “character.”

The Department of Justice sent Winner to prison for five years, the longest sentence ever imposed in federal court for leaking to the press. (Meanwhile, David Petraeus, the former CIA director who shared eight notebooks replete with the “identities of covert officers, war strategy, intelligence capabilities and mechanisms” with his lover-cum-biographer, got two years of probation and was fined $40,000—an amount that was later raised to $100,000 to “reflect the seriousness of the offense.”) In June 2021, Winner was released to a halfway house with an ankle monitor. She now works as a CrossFit coach and will, on commission, paint a portrait of your pet. The hardest part, she once said, was not the punishment but knowing that nothing changed and nobody cared.

Howley is refreshingly indifferent to the dreary imperatives of contemporary reportage, with its condescending assumptions about a reader’s attention span (short) and its dogma against “difficulty.” Her previous book, Thrown (2014), was narrated by a fictional persona, Kit (a philosophy grad student high on Husserl), but recounts the years Howley actually spent shadowing two mixed martial arts fighters on the make. Her feature for New York on the January 6 insurrection, a deeply humane portrait of three rioters, replaced quotation marks with italics and dispensed with self-justifying topic paragraphs.

It would be misleading to say that Bottoms Up and the Devil Laughs is a book “about” Reality Winner, whom Howley profiled for New York in 2017. Not unlike an NSA agent building out a “contact chain” for a target, Howley situates Winner within an idiosyncratic cast of whistleblowers and whistleblower-adjacent figures. Many of the book’s most memorable set pieces, drawn from archival news footage and public documents, have nothing to do with Winner at all, except insofar as they belong to the same post–September 11 American berserk that we’ve come to call the war on terror. Howley’s montage includes reconstructions of the CIA’s torture of Abu Zubaydah, the news show sound bites of the former CIA agent John Kiriakou (who’d improbably claimed for himself the mantle of torture truth-teller), and Lady Gaga’s interview with Julian Assange at the Ecuadorian embassy in London. (“It’s like you’re in college!” the pop star exclaims.)

Though Winner certainly gives good tape (the transcript of the FBI interrogation at her Augusta house was eventually staged on Broadway),* I was less convinced than Howley that the particulars of her situation, despite their heartrending absurdity, yielded new insights into the deep state or its surveillance powers. No doubt our behavior is tracked by a host of increasingly omniscient corporations. Nor is it a secret that when the government builds a case against any defendant, it does so by drawing selectively on evidence like Web browsing and diary entries, and it does so to win.

Advertisement

But Howley’s project is not to break news so much as it is to make these dismal facts felt and strange again. Thus she shows how Winner, before she was stripped of context by the media and the criminal justice system, was a prickly, idealistic teenager who’d fantasized about preventing another September 11, “a teetotaling liberal scold who spent her free time pushing wheelchair-bound children through marathons.” The building where Winner worked in Georgia—“more concert hall than facility, gleaming and white and gently, expensively curved”—is compared to “a giant piece of consumer technology newly unwrapped.” Drones are

cheap, flimsy, light little wisps of things, vulnerable to lost signals and sleepy pilots; vulnerable to gusts of wind and hard rain, lightning, ice; vulnerable even to themselves, as dropping a missile creates a thrust that threatens to spin a drone to the ground.

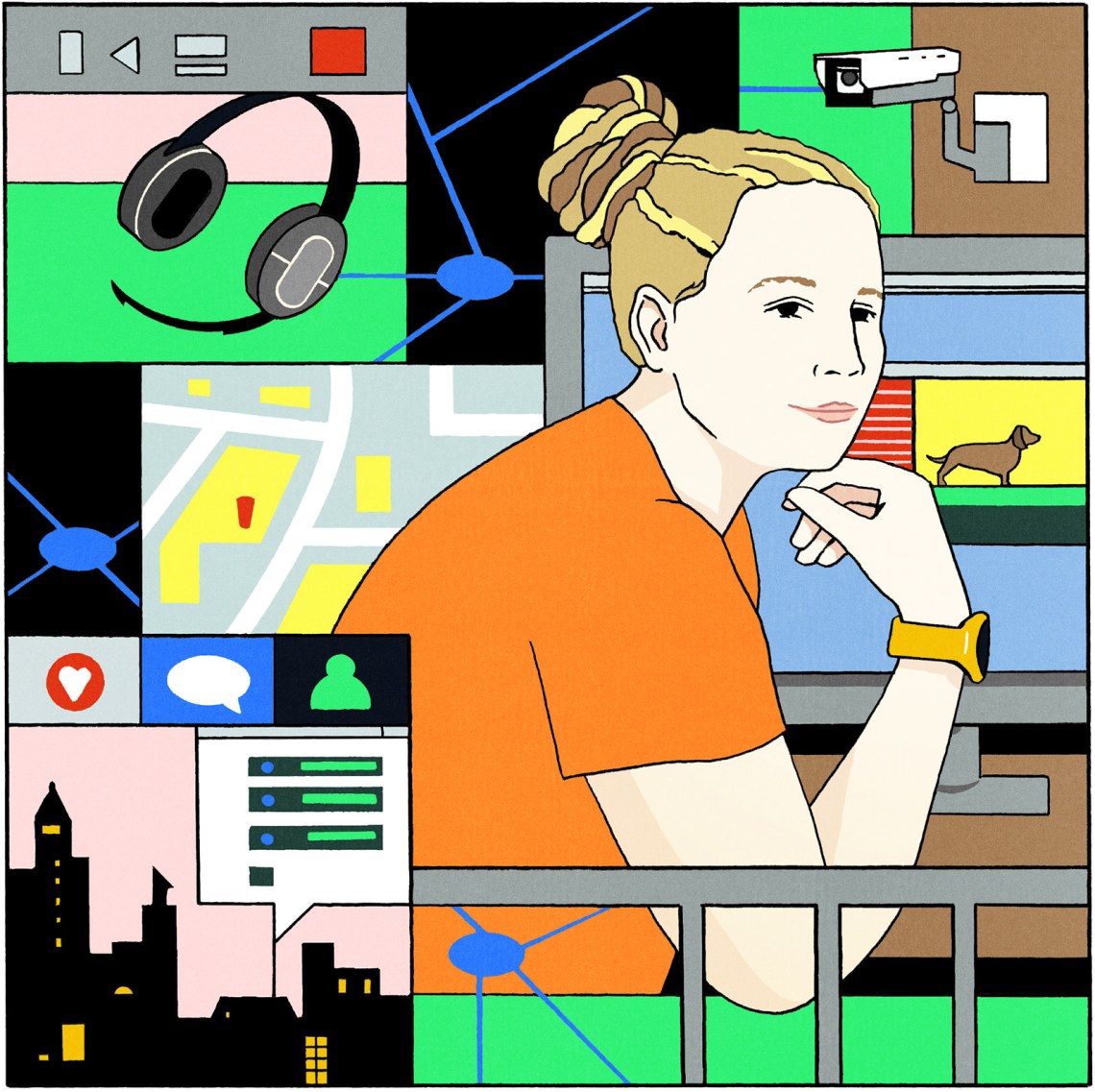

The book’s twitchy, antichronological form, meanwhile, mirrors the digital surveillance infrastructure that it describes, fusing “bits of information that, taken together, form a sclerotic social identity with a strange relation to the real.” The Internet condemns us to an eternal present tense, where old tweets can resurface with the same potency as those posted minutes ago. As surveillance becomes a way of being, we censure those who ghost, while celebrating the keepers of receipts. Privacy is no longer a matter of spatial arrangements, of walls and property; it is also a function of time. “We tend to think of privacy as the freedom to keep intentional secrets separate from public knowledge,” Howley observes, “but privacy has been the freedom to live as if most of what passes for experience will not endure.” Who owns the memories and histories you’ve docked at myriad social networks? Do you have a right to forget? To be forgotten?

Silicon Valley’s thick fog of euphemism has obscured the speed with which we’ve handed over our digital traces. To start-up founders and their epigones, there is no rapacious data harvesting, only personalization. No addiction, only engagement. No strangers, only friends. These companies care about the naked selfies and unhinged queries we’ve handed over to their air-conditioned servers insofar as that information can be used to sell us things. But the government, which can gain access to the materials, is a different beast. It consolidates our digital flotsam into a “sticky fiction,” and that fiction is backed by force:

There will never be a state from which there is no good reason to hide. The radical transparency we have accepted, step by step, these past years, is a bet we have made: that we and the people with the guns and cages will stay on good terms.

Reality and the state were not on good terms and so the state turned time backward and read the indelible history that she, like most of us, had offered into the ether.

In the course of preparing to write this review, I consumed a substantial, albeit incomplete, serving of Howley’s digitized output, assuring myself that such “research” would help me better account for her formation as a stylist. I learned that after graduating from Georgetown University, Howley worked at an English-language newspaper in Myanmar that was censored by the government, and that during her time there she traveled to Bangkok with two friends, one of whom she watched being pleasured by a local sex worker. After she was blacklisted by the Myanmar government, she returned to D.C., where she edited and wrote at Reason, the libertarian magazine. (Her interest in whistleblowers and the deep state seems to have emerged from this milieu, though her work never trades in stale, rightist, or paranoid critiques of the state as such.) On one particularly productive afternoon, I trawled through clips from the 2000s of her appearances on Red Eye, a late-night talk show on Fox, where she offered occasional deadpan commentary, parts of which have aged better than others, on buzzy stories like Paris Hilton’s arrest on suspicion of drunk driving.

I work as an investigative journalist, and it would have been easy, if I’d been so inclined, to use sophisticated subscription databases to supercharge my desultory browsing into Howley’s biography. With a few clicks, I could have gleaned her previous addresses, any criminal records, tax liens, bankruptcies, or registrations for hunting or fishing permits. With a little more effort, I might have been able to, say, tour the house she’d grown up in using Google Street View, dig up student evaluations from her time as a writing professor in Iowa and Tennessee, or see her selection of an extravagant gift on some accidentally public wedding registry. Plus, I’d clocked somewhere that she’d been her high school’s valedictorian—perhaps that speech was videotaped and posted online? It did not escape me that Howley, who presumably has log-ins to similar databases through her employer, could run the same searches on me (if she had nothing better to do).

Had I, or she, undertaken such activities, I would have defended them as reporting, not Internet stalking, though some outside the profession might argue that this is an unconvincing distinction. After all, one definition of journalism is the invasion of privacy in the public interest. Those hard-won findings—that paragraph where the ex-wife is revealed as an ex-con—are often made possible by the granular intel gathered by data brokerage firms whose products are but lame imitations of the programs deployed by the NSA. Yet the closest Howley gets to remarking on the discomfiting parallels between the journalist and the intelligence agent is when, in a rare lapse into koan-like syntax, she calls her book “a polemic against memory cast into print”—a provocation ambiguous enough to allow for the possibility that she is talking not just about a Facebook post but about the act of writing itself.

Listen closely to any journalistic critic of mass surveillance and you might hear not just rightful denunciation but hints of covetousness, too. Who among us conducting an investigation would refuse access to the Dropbox account or AT&T call logs of one of our so-called targets? (Some of the best magazine stories are, at bottom, prettified recaps of the revelatory documents that prosecutors can subpoena.) The slapdash dossier I’ve assembled on Howley is simple and unsinister. But it recalls her warning that once our data has been collected, it can be obtained—whether by an amateur snoop, a well-meaning journalist, or a government lawyer—and spun. Perhaps this is why Winner has written a memoir, set to be published by Spiegel and Grau. The NSA will be reviewing the text.

-

*

The play—called Is This a Room—is one of several recent popular representations of the Winner saga. A documentary, a dramatic adaptation of her interrogation for HBO (starring Sydney Sweeney), and a Hollywood biopic with a screenplay cowritten by Howley herself—titled Reality Winner, Reality, and Winner, respectively—have been or are about to be released. Winner has voiced support for the projects, but they make her uneasy. “There is this residual trauma of being in a jail cell and watching things about you on a TV screen that I physically can’t recover from,” she told Vanity Fair. “If I see or hear myself on any screen, I start shaking really bad because of that first year of seeing myself on the local news.” ↩