The fate of Raoul Wallenberg, the heroic young Swedish diplomat who saved the lives of thousands of Hungarian Jews before he was arrested by the Soviets in Budapest in early 1945, is one of the great unresolved mysteries of World War II. For decades, the official story from Moscow has been that Wallenberg died in Moscow’s Lubyanka Prison on July 17, 1947—two and a half years after he was captured. But many questions have surrounded that story, and now the Russians themselves have come up with startling new information suggesting that Wallenberg did not die on that date.

The new information appears in an 8-page letter from FSB (Federal Security Service) archivists to a pair of U.S.-based researchers, Susanne Berger and Vadim Birstein, who have been working on the case for years. In the letter, the FSB reveals that Wallenberg was “in all likelihood” the “prisoner number 7” who was interrogated in Lubyanka for sixteen hours on July 23, 1947, along with his driver in Budapest, Vilmos Langfelder, and Langfelder’s cellmate, Sandor Katona (both Hungarians). If the FSB is right, this is, first of all, a chilling admission that Wallenberg was subject to far more abuse than previously thought: it was known that he had been interrogated by the Soviets, but not in this extreme way; we can only imagine what he must have suffered at the hands of his brutal NKGB interrogators—and they were notoriously brutal—during that sixteen-hour session. More importantly, it also means that Wallenberg was still alive six days after July 17.

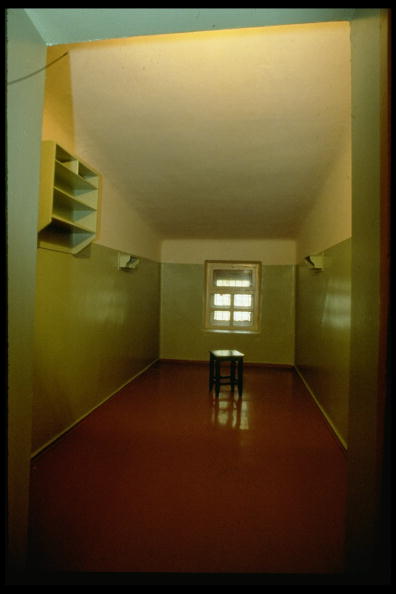

Why does this matter? Above all, as Susanne Berger told me, it re-opens the Wallenberg case by raising new possibilities about his fate. Wallenberg could have been killed immediately after (or during) his July 23 interrogation or he could have been kept in severe isolation in Lubyanka for several months and then executed. Another possibility is that he was sentenced and transferred to a distant prison, such as Vladimir, 250 kilometers east of Moscow, where quite a few witnesses said they met or heard of Raoul Wallenberg after 1947. Also, the new FSB evidence strongly suggests that—contrary to what the Russians have long maintained—documents related to Wallenberg still exist in the Russian archives. It may well be possible to determine, once and for all, the truth about his fate.

Several years ago I wrote a piece about Wallenberg for the New York Review, in which I discussed the findings of the Swedish-Russian Working Group on Raoul Wallenberg after the Russian archives first became accessible in the 1990s. Back in 1957 Soviet Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko had handed over to Swedish authorities a report signed by a Lubyanka prison doctor, stating that Wallenberg had suffered a fatal heart attack on July 17, 1947. But documents released from the Russian archives in the 1990s suggested that the heart attack never occurred and the doctor’s report was a cover-up. If Wallenberg had indeed died on July 17—the Russians insisted on this date, while the Swedes and independent experts for the working group remained unconvinced—it was probably by murder.

Until recently Russian archival officials claimed there were no more relevant documents on Wallenberg to be found, and the Swedish government stopped pressing the Russians for answers. But Wallenberg’s half-brother, Guy von Dardel (who died last year) and several other researchers who took part in the working group, including Berger and Birstein, insisted that the Russians were holding back key evidence. In 2001—inspired in part by von Dardel’s unflagging efforts to find out what happened to his brother—Berger and Birstein began corresponding with the officials who run the FSB archives about some of the unresolved questions.

Over much of the past decade, little progress was made. But in January 2009, a top FSB archival official, Vasily Khristoforov, suddenly admitted—in a long article in the Russian daily Vremia Novostei—that important questions about Wallenberg remained unanswered: Why did the Soviet special services need Wallenberg? What were the circumstances of his imprisonment? And, finally, how and when did he die? In stressing that the case was by no means closed, Khristoforov seemed to suggest that more information was forthcoming. That information came in late 2009, when the FSB sent the 8-page letter to Berger and Birstein. (Although the letter was delivered to the researchers via the Swedish Embassy in Moscow last November, they kept it under wraps until late March of this year; before going public in the Swedish magazine Fokus they wanted to study its contents and ask for further clarifications from the FSB archivists, as yet unanswered.) Why did the FSB reverse its position and raise the curtain, if only slightly, on a murky episode of the Stalin era?

The FSB would not take such a significant step in the Wallenberg case without the approval of the Russian leadership. It is probably no coincidence that the FSB’s revelation about Wallenberg has been followed by the Kremlin’s recent recognition of the 1940 Katyn massacre, in which the Soviet secret police executed more than 20,000 members of the Polish armed forces. In addition to allowing a Polish film about this terrible Soviet atrocity to be shown on Russian state television, the Russian government has for the first time acknowledged the historical significance of Katyn, in Prime Minister Vladimir Putin’s comments at the 70th anniversary commemoration of the massacre in early April. (A subsequent event, that was to have involved the Polish and Russian presidents, was horrifically overshadowed by the crash of the Polish delegation’s plane, though there is some hope that the tragedy will result in stronger Polish-Russian relations.)

Given the Kremlin’s blatant disregard for historical truth about the Soviet era, especially since Putin became president in 2000, this openness comes as a surprise. As recently as September 2007, at Putin’s behest, then FSB chief Nikolai Patrushev handed over purported archival documents on Wallenberg to the Chief Rabbi of Russia, Berel Lazar, for inclusion in a proposed Museum of Tolerance. Among the documents was the fake report saying Wallenberg had died of a heart attack.

The motivations behind the Kremlin’s recent shift remain unclear: perhaps it wants to obtain economic concessions from Europe, or perhaps there is a broader recognition by Russian leaders that coming clean about the Stalin period will bring them respect from the West and make it easier to advance Russian foreign policy aims. But surely the documentation about Prisoner No. 7 in the interrogation register did not appear out of the blue; there should be a larger file. And if Wallenberg was ultimately sent to a prison away from Moscow, there might be documentation in the archives of the MVD (Ministry of Internal Affairs). It’s time for the Swedish government (and perhaps the Americans and other Western leaders) to press the Kremlin leadership directly for answers.