Those who undertake additions to architectural landmarks ought to abide by the famous medical principle, “first, do no harm.” Thus the best one can say of Renzo Piano’s recently unveiled plans for a $125 million expansion of Louis Kahn’s Kimbell Art Museum of 1966–1972 in Fort Worth is that no fatal physical damage is about to be inflicted on what many revere as the finest of all modern gallery buildings.

However, this much-anticipated scheme, which will break ground this summer (it is scheduled for completion in 2013), is hardly what one had hoped for: a worthy companion to Piano’s glorious Texas triad comprised of the Menil Collection of 1982–1986 and the Cy Twombly Gallery of 1992–1995 in Houston, and the Nasher Sculpture Center of 1999–2003 in Dallas. With Minimalist architecture of the refined sort that Piano can excel at, there is a very thin line between magic and monotony, and this effort tilts decidedly in the latter direction.

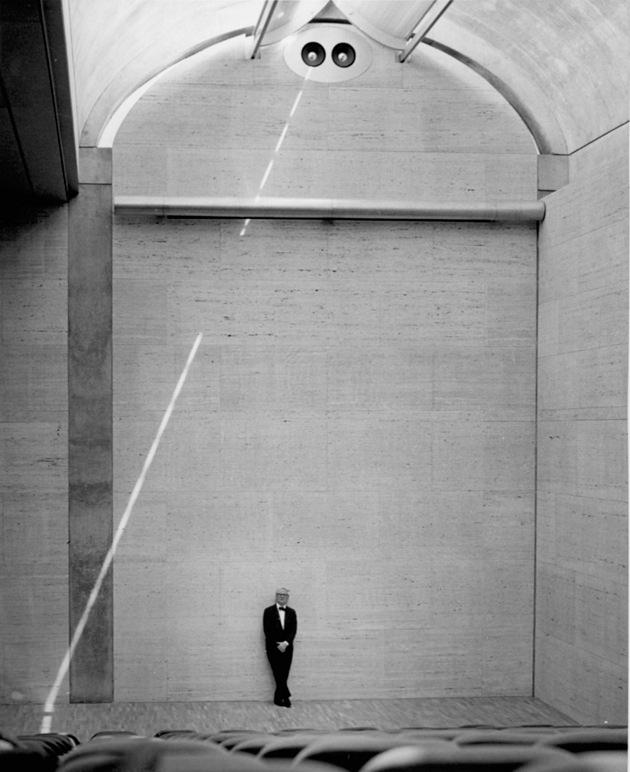

Kahn’s Classically inspired Kimbell—a series of parallel, domestically scaled galleries, each surmounted with a concrete barrel vault bisected by a long, slender skylight—is rightly renowned for a numinous quality of natural light filtered through an ingenious system of cradle-like ceiling baffles. The Kimbell’s exceptional significance was well recognized by 1989, when a disastrous expansion plan by Kahn’s erstwhile University of Pennsylvania colleague Romaldo Giurgola was precipitously withdrawn after a well-deserved international outcry.

Understandably, the announcement in 2007 that Piano had been chosen to design an addition to the Kimbell (which has one of the biggest endowments of any American art museum) was greeted with relief, even elation. After all, the young Piano had worked in Kahn’s Philadelphia office during the original Kimbell project, and he seemed guaranteed to produce a sympathetic design, not least because of his unparalleled understanding of how to modulate harsh Texas sunlight in gallery interiors to stunning effect.

Attendees at Piano’s May press briefing in New York, when the plans were first unveiled, were bidden to embargo their stories until the Kimbell board had approved the scheme at the end of the month, timing likely intended to circumvent negative press reaction of the sort that scuppered Giurgola’s proposal two decades ago. Inklings that this was a done deal were confirmed by news that the addition’s extra-long, custom-fabricated Douglas fir roof beams have already been ordered.

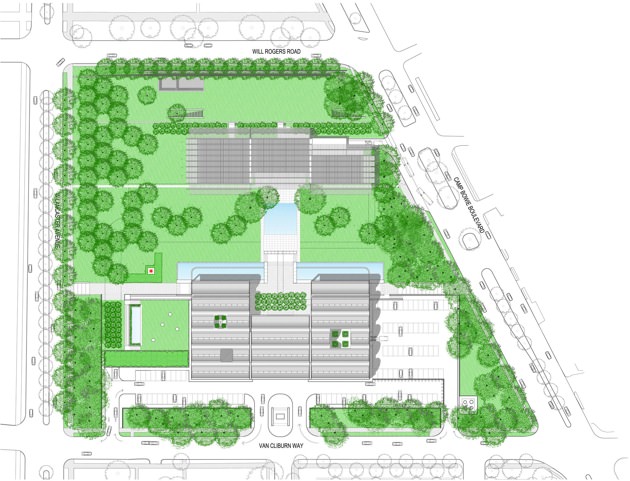

What Piano’s project also revealed is just how crucial siting is for the augmentation of any existing structure, especially a true masterwork. After the Kimbell engaged Piano three years ago, it became known that he would not directly extend Kahn’s original, as Giurgola had planned, but instead build across the street on a property the Kimbell owns but at present is used as a forecourt parking lot for Tadao Ando’s Fort Worth Museum of Modern Art of 1999–2002 (one of the Japanese architect’s less fortunate projects in the US).

Therefore it came as a considerable surprise to learn at the press conference that the new wing won’t be located at that welcome remove after all. Rather, the freestanding addition will rise along the west side of the Kahn building and devour much of the beloved swath of parkland between the Kimbell and Philip Johnson’s Amon Carter Museum of 1958–1961, another linchpin of Fort Worth’s estimable arts district.

The consequences of this decision by the Kimbell and its incumbent architect seem likely to be unfortunate. Obviously trying to gloss over journalists’ questions about this unexpected change of venue, Piano and the museum’s director, Eric Lee, claimed that the capacious parking-lot plot was abandoned because it was inconvenient for pedestrians to reach; it had proved impossible to close off the street that separates it and the Fort Worth MoMA from the Kimbell. They also asserted that the new wing would, in any case, have been “too far” from the Kahn building (though the distance cannot have been more than a few hundred feet).

Kahn (1901–1974), whose building career was long delayed by the two-decade construction hiatus imposed by the Great Depression and World War II, never became a facile designer. He struggled at midlife to gain his artistic footing because of a relative lack of hands-on experience, but with the Kimbell he at last hit his stride. His daughter, the flautist Sue Ann Kahn, recently told me that during his Fort Worth job he reported to her that “I felt as if someone else’s hand was doing it,” a phenomenon she likened to Mozart’s experience of composing music as akin to taking divine dictation.

Advertisement

In orchestrating his Kimbell addition, Piano was attuned to the need for maintaining harmony with Kahn’s lyrical composition. Piano’s design hews closely to his familiar formula of the low-slung colonnaded pavilion with overhanging eaves. It also echoes the lateral dimensions of Kahn’s Kimbell to a degree that paradoxically undermines the original by reflecting it too closely.

The rear half of Piano’s freestanding wing will be concealed beneath a grassy berm to minimize the bulk of the new 23-foot tall structure, whose 85,000 square feet will be largely devoted to educational programs and galleries for changing exhibitions. (Roughly doubling the gallery space of the Kimbell, it is closer to a duplication than a mere addition.) The two buildings will stand just ninety feet apart, separated by a plaza atop a new subterranean parking garage through which most visitors will arrive. (There is already an above-ground vehicular lot on the east side of Kahn’s building.)

To give the space between the old and new Kimbell galleries more visual interest, Piano has planned a large square reflecting pool at the center of the space between the two buildings, another serious miscalculation. This water feature will be just a few feet away from Kahn’s symmetrical pair of raised “infinity” pools, the most sublime fountains in all of modern architecture, because of the immensely subtle way in which they reiterate the Kimbell’s long extruded proportions and upper curvature. With such insuperable competition, it is inadvisable to place more water anywhere nearby, which can only dilute the impact of Kahn’s hypnotic cascades.

Most troubling is that the Kimbell feels compelled to aggrandize what is universally esteemed as one of the world’s perfect small museums. Of course many museums want more space to display works they cannot show or to accommodate changing exhibitions. But today’s mania for museum expansionism, apparently undiminished by the global recession, falls in with the “grow-or-die” mentality of benefactors on whom cultural institutions everywhere have become increasingly dependent at a time of diminished governmental support. Good times or bad, Piano remains the world’s most sought-after architect among arts patrons, and currently is at work on projects as far-flung as additions to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and Boston’s Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum; a new building for the Whitney Museum of American Art in Manhattan’s Meatpacking District; and the Niarchos Cultural Center in Athens, which will comprise Greece’s new national library and opera house.

The Kimbell should feel honored to be in the same tiny, exalted league as New York’s Frick Collection and London’s Wallace Collection, rather than trying futilely to compete with constantly enlarging museums that will never approach its inimitable combination of superlative art displayed in surroundings of embracing intimacy and unsurpassed architectural quality. One hopes for the best, but one also wonders whether future generations will ask why the Kimbell didn’t leave splendid enough alone.