When I met Tony Judt twenty years ago, he was on his way to catch a train. But he lingered instead in Providence to lunch with a couple of Brown University undergraduates. He gently gave career advice to two young men hesitating between history and journalism. Of course I wouldn’t suggest that whoever had a meal with Tony either became a historian, as I did, or won the Pulitzer Prize for journalism, as did Gareth Cook. But Tony was always exceedingly generous with his time, especially with younger people. Brief requests for advice yielded pages of well-crafted counsel. He wrote letters of recommendation for dozens of people who were not formally his students, and organized conferences at which younger people met more established scholars. At his Remarque Institute at New York University, the criterion for participation was merit rather than renown.

Tony Judt was, in effect, two historians: first, a Marxist from a working-class English-Jewish background educated at Cambridge and at the École Normale in Paris who wrote four excellent books on the French left, and then a grand New York scholar who wrote an unimaginably good history of postwar Europe as well as strikingly clear studies of leading European intellectuals, such as Albert Camus and Leszek Kołakowski. The hinge was Past Imperfect, Tony’s eloquent critique of Parisian intellectual politics after World War II, published in 1992. On the surface, this was a close study of Jean-Paul Sartre’s communism and the political narcissism of Left Bank intellectuals who celebrated Stalinism while ignoring its consequences in Eastern Europe. At another level, it was the repudiation by a French Marxist of his own tradition.

Tony wrote his first book, La Reconstruction du parti socialiste, 1921–1926, in French; one French reviewer rightly noted that Past Imperfect read like an argument by a living French intellectual with several dead ones. Fundamentally, Past Imperfect was Tony’s first attempt at a philosophy of history that would survive the crash of Marxism and of the other great political and intellectual systems of the twentieth century. Yet even as he distanced himself from French Marxists, Tony resisted the temptation to substitute another source of intellectual authority for Marxism. Whereas some intellectuals of his generation replaced Marxism with something that seemed like its opposite—the market, for example—he instead rejected the very idea of a single underlying explanation of historical change.

Past Imperfect was possible because Tony had taken, during the 1980s, a kind of mental journey to Eastern Europe, against the drift of his own profession (Western Europeanists remaining such, despite the upheavals in Eastern Europe) and family history (Jews moving west from the Russian Empire). This intellectual move was more fruitful, if less dramatic, than his political encounters with the Jewish state. His youthful Zionism was a halfhearted rebellion against his parents, who wanted him to study in England; his later critique of Israel was, among other things, a kind of self-criticism. More interesting was his midlife participation in Eastern European intellectual life, which hastened the break with Marxism and enabled a more capacious view of the continent. Born in 1948, Tony was the same age as the generation of rebellious Polish intellectuals (often of Jewish origin) who were beaten, imprisoned, and expelled from Communist Poland in 1968 in an anti-Semitic campaign. Some of these people (notably Jan Gross, Irena Grudzińska-Gross, and Barbara Toruńczyk) befriended him in the 1980s, and their history, in a crucial sense, became his own.

In 1968, Tony was still both a Zionist and a Marxist. His Polish generational peers had never been Zionists (though they were called such by the Communist regime) and had been thinking their way out of Marxism for longer than he. In 1968, Tony, then twenty, took part in student demonstrations in Paris, London, and Cambridge; after an antiwar demonstration in Cambridge he trotted back to King’s College, chatting amiably with a policeman, hoping to reach the dining hall before the dinner bell rang. Two decades later, as a man of forty, Tony saw how different this was from police batons in Warsaw, and allowed the experiences of his Eastern European friends to overlay his own and enrich his understanding of postwar Europe. He was able to imagine that his own life (his father’s father was born in Warsaw; there were Judts in the Warsaw ghetto) might have taken a course like that of his friends. In the 1980s, Tony was teaching at Oxford, as was Leszek Kołakowski, the Polish philosopher who had been the intellectual inspiration of the Polish students of 1968. In one of his late New York Review essays, Tony wrote brilliantly on Kołakowski’s masterwork, Main Currents of Marxism, the most faith-corroding history of the subject.

Advertisement

Many historians reacted to the end of faith in overall explanations by becoming experts in a narrow or specialized subject. In the 1990s, as he prepared himself to write Postwar, Tony chose a harder path. Like Isaiah Berlin, another influential contemporary at Oxford, he accepted the irreducible variety within history, seeking to embrace difference within an account that was harmonious, convincing, and true. Tony brought together not only Europe east and west, but also Scandinavia and the Mediterranean. He wrote with equal authority about economics, society, politics, and culture, and granted the value of specialization by mastering the huge literatures of these fields, to which he imparted grace and unity.

Tony’s identity was cosmopolitan, but the breadth of his languages and knowledge concealed a certain unease. Once, at a conference in Berlin, the former East German spymaster Markus Wolf maliciously asked him to repeat a question in German. Tony did so, but with a kind of hesitation that was uncharacteristic of him. Having spent much of the last two years working on his biography, I now believe that I know the first sentence that he ever spoke in German. In 1960, when Tony was twelve, he and his family had to stay a night in Germany on the way to a summer holiday. On his father’s side his family were Eastern European Jews who had settled in Belgium, several of whom were murdered in the Holocaust. Tony was named after a cousin of his father’s who was killed at Auschwitz. His father could not bring himself to speak to the Germans at the reception desk, so he instructed his son what to say: “Mein Vater will eine Dusche“—my father wants a shower. The Holocaust, on Tony’s account, was everywhere and nowhere in his upbringing, like a vapor.

Much the same is true of the presence and absence of the Holocaust in his historical work. All of the early books about the French left ask, if only implicitly: Did it have to happen? Couldn’t socialism have triumphed rather than National Socialism? Mightn’t France have prevailed rather than Germany? Wasn’t enlightened politics somehow still possible? Even in Past Imperfect Tony had little to say about the French experience of German occupation and the crimes of Vichy. In Postwar he generally left the Holocaust out of the history, commenting in his conclusion on how it has been commemorated rather than focusing on the event itself. Like many other historians of his generation, Tony for some time wrote as if he believed that the great themes of intellectual and political history could be addressed separately from the Holocaust. But the mass murder of Europe’s Jews, as he told me, “keeps intruding.” When he fell ill, he was preparing himself to write an intellectual history of the twentieth century that would accommodate its major tragedy. It was only at the very end, in the work composed during his final illness, that Tony closed this circle.

Tony used the horror of ALS to breach some of his few intellectual limits. By 2008, when he was diagnosed, he held a chair, directed an institute, and was recognized as a historian and writer. All of this he had achieved on his own terms, rebelling when he liked and against whom he liked, always defining himself as an outsider. I think that the disease made that distinction between insider and outsider, though important to Tony throughout his life, much less relevant. Trapped inside his own body, he went outside of himself in a way that he had never done before. Mindful of his physical appearance after an earlier bout with cancer, and a private person throughout his life, Tony now exposed his wracked form and his complicated biography.

In late 2008 he agreed to compose, with my help, a long book about his life, and the life of the mind in the twentieth century. This work, which considers the major currents of twentieth-century thought, reveals the scope of Tony’s knowledge of intellectual life more vividly, I think, than anything that he had previously done. In its composition, his great pride cooperated with his great humility. As we completed six months of conversations, Tony began again to work on his own, dictating the short essays published in The New York Review, and composing the lecture on social democracy that he quickly expanded into the book Ill Fares the Land. We completed Thinking the Twentieth Century this July, a few weeks before his death.

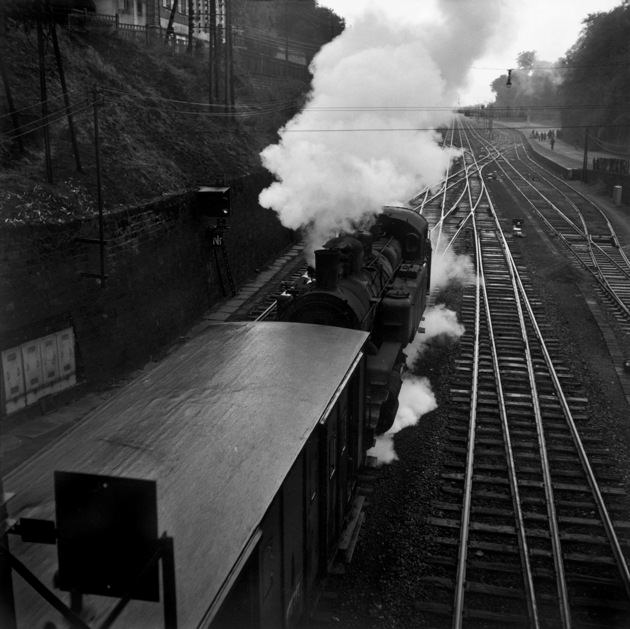

When I last wrote to Tony Judt, not long before he died, I had just returned from a trip by train in Austria. Tony having made the same journey from Vienna to Krems and back with one of his sons, we exchanged e-mails about rail travel along the Danube with little boys. Thinking the Twentieth Century realizes one of the two books that Tony knew he wanted to write. The other, Locomotion, was about travel by rail. Precisely because he was unsentimental about his Jewish boyhood in London, he was nostalgic about the British trains. His school was built between the rail lines running from Victoria and Waterloo stations, suggesting routes of imaginary escape. As a teenager he would take his bicycle on the train and go exploring for the day. At the time he thought he was running away; with time he came to see that he was journeying among others. Travel by train, he came to think, is how society provides for itself, and finds itself along the way. Tony told me that one of the sadnesses of his illness was that he would never again find himself on a railway platform, uncertain of destination but certain of progress. Yet Tony was always in motion, even when he could no longer move, first pacing through an incomparable library of remembered books, then treading back and forth to find vistas upon an admirable life, ever revealing the limits of others, but always setting an example by overcoming his own.

Advertisement

A longer version of this post will appear in the New York Review of Books.