The static art of architecture and the kinetic art of motion pictures might seem antithetical mediums, but films can be enormously helpful in explaining buildings to laymen and professionals alike. Certain architectural works—the photo-resistant designs of Alvar Aalto come to mind—are difficult if not impossible to understand in still imagery, and are made fully comprehensible only through films that move around and inside them.

The first Architecture and Design Film Festival, being held in New York today through Sunday, offers a rare opportunity to see in close succession more than forty examples of the genre (which vary in length from two to eighty minutes).

The standard monographic approach to such films is typified by Scott Huegerich and Bill Miano’s The Gateway Arch: A Reflection of America (2006) (not included in the festival), a straightforward historical narrative about Eero Saarinen’s gigantic stainless-steel parabola at the United States Jefferson National Expansion Memorial of 1947–1965 in St. Louis. But the festival calls attention to some more unconventional approaches, among them the arresting look at an individual building afforded by John Halpern and James Venturi’s Saving Lieb House (2010), which captivatingly documents the sea voyage of a small 1960s vacation residence by the co-director’s parents, Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown, from its original site on the Jersey coast to its new home on the North Shore of Long Island.

Robert Venturi’s most important early advocate was Vincent Scully, who taught architectural history at Yale for more than half a century. Edgar Howard’s Vincent Scully: An Art Historian Among Architects (2010) pays tribute to this charismatic lecturer and pioneering scholar of the American Shingle Style and indigenous vernacular traditions. Scully, who turned 90 this year, has done more than any other postwar educator to convey to non-specialists the importance of architecture in society, and this affectionate portrait emphasizes his insistence that all buildings, ancient as well as modern, must be understood as part of their environmental setting.

Unfortunately, the film does not place Scully among his contemporary peers—the technocentric British architectural historian and critic Reyner Banham, for example—nor does it ever directly explicate his singular accomplishment in establishing, almost singlehandedly, the reputations of Louis Kahn and Venturi, the two foremost architects of the second half of the twentieth century.

The most affecting festival entry is Sam Wainwright Douglass’s hour-long Citizen Architect: Samuel Mockbee and the Spirit of the Rural Studio (2010). The admirable Mockbee, who died in 2001 at the age of 57, devoted the last eight years of his tragically truncated career to the Rural Studio, a design/build program he founded at Alabama’s Auburn University to provide housing for the poorest residents of that state’s so-called Black Belt.

Like a funky Habitat for Humanity, Mockbee and his students recycled materials including license plates, indoor-outdoor carpet tiles, plasticized cardboard, and auto windshields to create quirkily individualistic but eminently livable dwellings and community structures. Historians often call the 1920s in Europe the “Heroic Period” of modern architecture, but the building art doesn’t get more heroic than the quiet crusade Mockbee set in motion.

Oddest of all is Teri-Wehn Damisch’s Citizen Lambert: Joan of Architecture (2007), a biographical tribute to Phyllis Bronfman Lambert, the Canadian distillery heiress and architecture patron, on her eightieth birthday. It was made with the subject’s co-operation, as evidenced by her clowning in funny poses for the film’s gimmicky animated effects, which include Lambert in a snow-globe, an homage to Orson Welles’s famous Rosebud sequence in Citizen Kane (1941). Nonetheless, the film is surprisingly frank about the darker side of its diva-like protagonist. As Lambert observes, her notoriously tyrannical, foul-mouthed father, Samuel Bronfman, head of the Seagram Company, “could see himself in myself.”

Lambert is best-known for her pivotal role in the commissioning of Ludwig Mies van der Rohe and Philip Johnson’s Seagram Building of 1954–1958 in New York City, and for her founding, in 1979, of the Canadian Center for Architecture, the world’s foremost archive and museum devoted to the subject, in her hometown of Montreal. Long a ubiquitous presence on the worldwide architectural lecture and conference circuit, Lambert preposterously insists throughout that she has been “always on the outside.”

As Lambert’s life story suggests, her miserable childhood—“my imprisonment,” she calls it—and her socially marginal status as a Jew in Catholic Quebec and the daughter of a shady operator left her with insecurities that great wealth could never efface. It is hard not to feel some sympathy for this classic poor little rich girl.

Advertisement

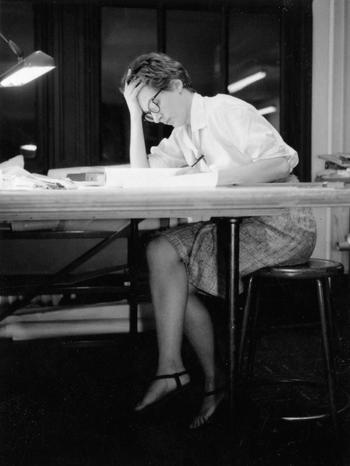

After Vassar she married briefly, tried to become an artist in Paris, and then studied architecture, first at Yale, which she left because, she defensively relates, “They were so ungenerous to people they thought didn’t have talent.” (Later she would get a degree from the Illinois Institute of Technology.)

She found her true calling in 1954, when, appalled by a banal scheme her father chose for Seagram’s American headquarters on Manhattan’s Park Avenue, she blackmailed him emotionally into letting her take charge of the high-profile, big-budget scheme by telling him that if he did not accede “you no longer have a daughter,” as Lambert recalls. The bullied bully Sam Bronfman acquiesced, and his daughter settled on Mies, who asked Johnson to assist him for what would become the masterpiece of Mies’s American career.

The star of Citizen Lambert goes on at length about her reputation for “impatience,” as if that were the reason so many people have found her difficult to deal with. More to the point is the New York–based architect Elizabeth Diller (one of the designers of Manhattan’s acclaimed High Line), who tells of a visit Lambert paid to her office straight from an unpleasant journey to the city. Diller is a brave woman, for she unblinkingly recounts that after she offered her harried guest a hot drink to calm her down, Lambert snapped, “I don’t want your fucking tea!”

When an interviewer asks Lambert what it was like to be a 27-year-old thrown into such heady company as Mies and Johnson, she bristles, “I wasn’t thrown in, I fought my way into it.” Although her path through life has certainly been smoothed considerably by privilege, Lambert’s turbulent history parallels the struggles faced by other aspirants who take on an art form that can be as cruel to its practitioners as it can be rewarding to its sponsors and its users.

The Architecture and Design Film Festival is showing at New York’s Tribeca Cinemas, October 14–17, 2010.