“When Jerry Griffin, 49, an admissions counselor at the University of California at Davis, showed up for work wearing a skirt, he was told to take it off …”

“Marie Darrieussecq has the body of Lolita, the intellect of Sartre, and a mind as filthy as the Marquis de Sade’s. Fame has come easy …”

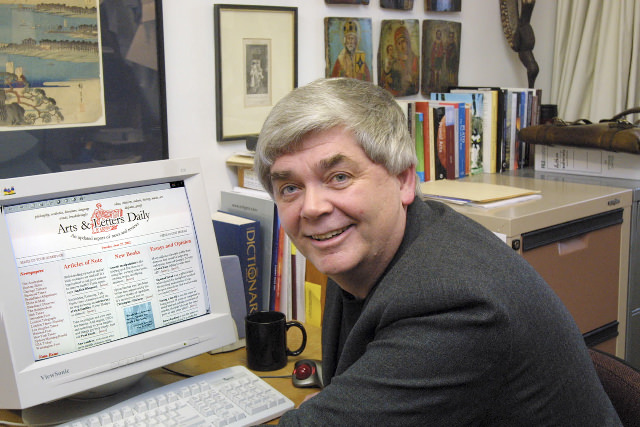

Either of these stories could go in several directions, and into several very different genres. The only way to find out is to read on. And that, in brief, has been the secret of the success of Arts & Letters Daily (ALD), a website recommending articles on the Internet worth reading. Its founder, Denis Dutton, died last month at the age of 66.

The teaser about the skirted counselor was one of the first that Dutton wrote for ALD, in 1998. Already, his capacity to tease was fully developed. (The original link is broken, but you can find a version of the story here.) The second, about a young French-Basque novelist, comes from 2001, and is pulled at random from thousands more such posts in the ALD archive.

As others have remarked before me, Dutton was, in effect, a master of the tweet long before Twitter was invented. He knew how to capture and project in just a few words, not so much the essence of a story, as the zest or the mystery of it. Really, it was the opposite of precis writing. Having read Dutton’s teaser, instead of thinking, “Well, now I know what that’s about,” your reaction would be, “What on earth is that about?” and you would click dutifully on the “more»” link to find out.

For a man of his age and background—a non-techy, 50-something, university professor—Dutton was a crucial few years ahead of his time in understanding the Internet. He saw its potential as a publishing platform. (He was also an early publisher of e-books.) He anticipated information overload. With ALD, he identified a market for what media people now call “curating,” which is to say, selecting and recommending content for a particular audience. All this was at a time when the Web was still, by and large, a morass of dial-up connections and bad typography in need of a decent search engine. (In 1998, Google was still in a garage.)

One of ALD’s many strengths was the old-fashioned restraint and elegance of its site design. It aspired, not to the kinetics of any other contemporary website, but to the untroubled air of an 18th-century broadsheet. (Dutton also cited the influence of a 19th-century New Zealand paper, the Lyttelton Times.) It posed as a website for grown-ups. It was as if Dutton operated a back-channel on the internet for older and grander people who otherwise considered reading on a computer to lie somewhere between a perversion and an impossibility.

Well before his creation of ALD, Dutton was a name within the academic world. He founded the learned journal Philosophy and Literature in 1977, and widened its fame greatly in the 1990s by launching a “bad writing contest,” mocking impenetrable academic prose, which in spirit complemented the Sokal Hoax (after Social Text had published his bogus paper, Alan Sokal published his afterthoughts in Philosophy and Literature).

When Dutton launched ALD, its success was immediate. Within a year, it was reporting 250,000 visitors a month, a large number for those days. Four publications vied to take it over. Lingua Franca prevailed. After Lingua Franca went bankrupt in 2001, the Chronicle of Higher Education succeeded as proprietor.

If readers loved ALD, writers loved it all the more. A mention in its columns brought the recommended article legions of readers—most of whom would otherwise have missed or skipped over it. In 2006-07 I built and ran a small website for The Economist magazine’s lifestyle quarterly, “Intelligent Life.” In its very early days, that site would hope for 3,000-5,000 visitors a day. A mention in ALD would bring in an extra 15,000-20,000.

Dutton thus enjoyed tremendous soft power in the world of journalism—flanked by his long-time collaborator, Tran Huu Dung, a professor of economics at Wright State University in Dayton, Ohio, who has since taken charge of ALD. I don’t suggest Dutton ever misused, or even actively exploited, this power, but I do feel sure that he must have enjoyed the sense of the media at large vying for his goodwill with admiring profiles and implausible accolades. (See here, here, and here.)

I see an extension of this phenomenon in the reception afforded Dutton’s last book, The Art Instinct, in 2009. Browsing through the reviews cited on book’s website, it is notable (to me) that the very occasional dissenting voices are, with few exceptions, from specialist publications. By and large, reviewers in the general-interest media profess to be overwhelmed: whether by Dutton’s “magisterial command of the history of aesthetics,” or his “masterful knowledge of art” or his “rich and persuasive argument for the centrality of art in our evolution” (the book is, in fact, about the centrality of evolution in our art).

Advertisement

To quote from one (generally favorable) review, the book’s central contention is this:

Artistic expression must be understood in Darwinian terms as having survival value, originating in early hominid adaptation to the conditions of life in the African savannas of the Pleistocene era … Thus fiction, as we know it, has evolved from the role of the storyteller, who, enchanting his audience around the prehistoric campfire, helped them to a richer understanding of the lives of others and of the wider world around them, fostering their better adaptation to their Pleistocene environment …

It also salutes Darwin’s theory of sexual selection:

Just as the peacock’s tail is designed to attract the peahen, the warbler’s song the female warbler, and the lion’s roar the lioness, so the various beauties of art, music, and dance evolved as means of demonstrating their creators’ superior reproductive fitness.

The joy of Dutton’s thesis in The Art Instinct is that it cannot be proved, one way or another. To me it seems to be almost as absurd as its corollary, that concepts of beauty remain broadly constant across cultures. The relevant history is not available to us, and, absent time machines, will never be recovered. Dutton’s book is a work of the imagination, poised between logic and fiction.

I say this in admiration. Dutton’s genius lay not in his philosophy, but in his capacity to provoke intelligently. Look at him speaking at a TED conference last year, and you see not only a thinker, but also a charmer, a gentle bruiser, an ironist. Even more than an intellectual, he was an intellectual entrepreneur. In The Art Instinct he found a captivating idea that built on winning themes—evolution, beauty, sex—and he advanced it as if it were truth. At Philosophy and Literature, his great legacy was not so much the promotion of good writing, which all journals have as their object, but the destruction of bad writing, which few in the academy were brave enough to attempt. At ALD, he found his relative advantage not in the production of fine writing, but in the boutique retailing of it, to the benefit of everyone: writers, readers, Dutton himself.

There was much more to this marvellous man. I pass over lightly his passion for public radio, his university career in New Zealand, his sitar-playing, and his more contentious website, Climate Debate Daily, in which his libertarian conservatism may have got the better of him. If only there were a “more»” link at the end of Denis Dutton’s life, I would be clicking on it now.