When I thought of writing a book about Bill Buckley, who first made his name as the chairman (editor in chief) of the Yale Daily News, I went to New Haven to interview Francis Donoghue, the longtime business manager of the paper. Buckley had worked hard to be elected chairman, but his aggressive politics made him feel he had no lock on the job. He asked his older brother, Jim, who had worked on the Daily News before him, if it was proper for him, as a member of the editorial board, to vote for himself. Jim said that the vote was anonymous, so no one would know how he voted. When the vote was unanimous, everyone knew.

I told that story to Donahue, and he said Bill should never have had any doubt, since he was the most respected as well as the most flamboyant editor the paper ever had. I asked whom he would consider the next most outstanding editor of the paper. Without hesitation he said “Sarge Shriver.” There have been many famous men (only men back then) who held that post, so this was an extraordinary tribute. I did not know Shriver then, though I knew of him of course, and that was in my mind when I met him.

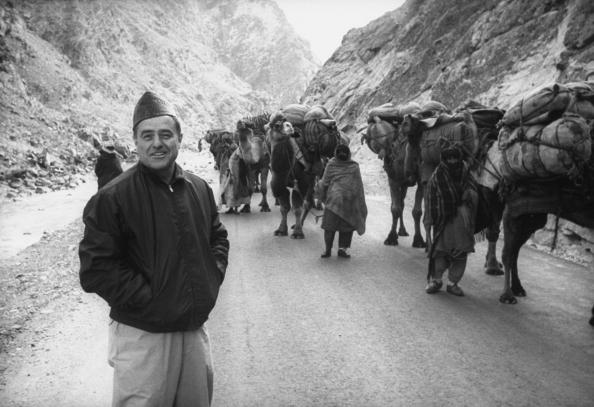

Robert Sargent Shriver became somewhat overshadowed by the Kennedy family he joined when he married JFK’s sister Eunice in 1953. When I went to his home in Maryland, the pictures around the house added up to a shrine to the Kennedys. But his family was an older political line than that of the Kennedys. The Shrivers of Union Mills, Maryland, had been prominent since David Shriver signed the Maryland constitution, and the family was known for producing judges, professors, and business leaders throughout the state’s subsequent history. Sarge Shriver himself was, among other things, the first director of the Peace Corps.

I got to know him when he was running for the vice presidency in 1972. He invited me to his home for lunch and dinner and asked me to write speeches for him. He knew me partly because I wrote a column for the National Catholic Reporter, and he (like Francis Donahue) was a devout Catholic. I told him I did not write speeches for political candidates. He remembered that when he ceased to be a candidate, and called to ask me if I wrote speeches for non-candidates. I never had, but for him, the winning, likeable, upright man, I said I could make an exception. He was about to go to France as our ambassador, and he wanted me to write a speech about Jefferson as our envoy there.

I said I would write it and send it to him. He said, “Oh no, I’ll come get it in Baltimore.” He drove over and we went through the speech, sentence by sentence, on the couch in my living room. He was radiantly friendly with my children, and I saw why no one I ever talked to about him had anything bad to say about him.

After my book, The Kennedy Imprisonment, came out, his wife expressed her disapproval of me, but I never thought he would have. And, sure enough, when my book Why I Am a Catholic appeared, his assistant wrote asking me for an inscribed copy of it. I am certain he never asked himself why he was a Catholic. But Francis Donahue is surely greeting him in heaven today.