When invited by The New York Review to write about the very successful western (if it is a western; about which more follows) and Coen brothers movie adaptation of Charles Portis’s twice-filmed novel True Grit, we watched Henry Hathaway’s 1969 version starring John Wayne and Kim Darby, Joel’s and Ethan’s version, and also read Portis’s much-praised novel, on top of which we breezed through quite a few reviews, as well as portions of the production notes.

The story of True Grit is mainly a study of loyalty. Reluctant loyalty, it is true, but loyalty nonetheless. The reluctance that fuels the narrative belongs to the aging, cranky bounty hunter Rooster Cogburn (Jeff Bridges) who finds himself cornered one day by the extremely persistent Mattie Ross (Hailee Steinfeld), a fourteen-year-old girl from Yell County, Arkansas, who is determined to avenge the murder of her father by the renegade Tom Chaney (Josh Brolin). Not only does Mattie hammer at Rooster until he agrees to go catch the killer, he is unable to dissuade her from coming with him, even into the wilds of Indian Territory, where they are joined in their search by a Texas Ranger, La Boeuf (Matt Damon). In the wilderness of the Choctaw Nation, this quarrelsome threesome develop bonds that are tested in violent conflict of a sort common in frontier yarns.

So what do we learn about loyalty in True Grit? That it doesn’t prevent disagreement, or out-and-out fights, but it is often the coat love wears—a tattered and ragged coat, as in this fine movie—but maybe, just maybe, the best thing we have. Following is our conversation about all of the above, which we hope some readers will enjoy.

Diana Ossana: I liked my second viewing of the Coen brothers’ True Grit much more than the first—and I did like the first viewing—and I know why: the sort of stilted, formal language took some getting used to. I was expecting it this time, so it wasn’t at all distracting.

Larry McMurtry: Well, it’s in a certain tradition. I didn’t mind the language too much, but I thought the book and the film were both prolix, the conversations ran on too long and could have been shortened by a few sentences. Example, the conversation between Mattie and the horse trader about the price of Texas ponies. I think the Coen brothers’ True Grit is a wonderful movie, though, and they know their craft, which they practice with a certain elegance.

D: But you said while we were watching their version that the dialogue was too formal at times.

L: I did.

D: Contrary. But I agree, I loved the film, particularly Jeff Bridges’s performance as Rooster Cogburn, and the Carter Burwell soundtrack. The Coen brothers are smart and unsentimental, two of my favorite traits in men.

L: That’s why we get along to the extent that we do get along.

D: Fine.

L: An example of their elegant filmmaking is the verse from Proverbs that they use as an epigraph on a black screen: “The wicked flee when none pursueth.”

D: Which is a perfect epigraph for Mattie and her journey, and Jeff’s character, too.

L: The Coens each read Portis’s True Grit to their children.

D: I found that it does read like a novel accessible to young people.

L: I think Donna Tartt, the critic who contributed the afterword to the paperback, was right to mention that it owes more to The Wizard of Oz than to Huck Finn …

D: … because of the relentlessness of the young heroine. Dorothy wants to get back home to Kansas; Mattie wants to avenge the murder of her father at the hands of Tom Chaney. The language might feel similar to Twain’s, though Portis’s dialogue is more formal. I loved reading Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn growing up, and in fact that’s where my belief that boys have more fun than girls originated. I enjoyed True Grit the novel because a girl was having the adventures for a change.

L: You would like that.

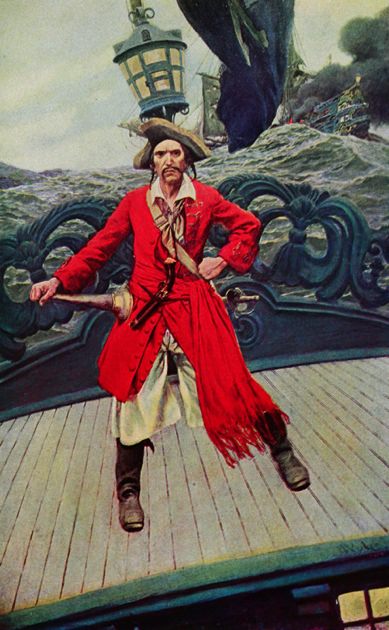

D: The late-nineteenth, early-twentieth century illustrator Howard Pyle was an influence on the Coens’ creative vision for True Grit. Pyle also wrote and illustrated a book on King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table, too. The illustrations are dramatic and memorable, especially for a ten-year-old girl who lived mostly in her imagination.

L: I think it’s interesting that they drew their visual inspiration from illustrators like Howard Pyle and N.C. Wyeth, who did young adult classics, like Treasure Island and Kidnapped and The Book of Pirates. I see that particularly in the Tom Chaney, La Boeuf, and the bear man. [Mattie and Rooster encounter a “bear man,” a mountain man wearing a bearskin, in Indian country.]

Advertisement

D: The bear man was a creation of the Coens. He reminds me of one of the characters in your western novels. Night of the Hunter, the Charles Laughton movie about innocents facing murder and mayhem, was their inspiration for some of the music. “Leaning on Everlasting Arms” which plays during Rooster’s anguished, redemptive ride with Mattie was used throughout that film, too.

L: Indicative of how the Coen brothers have arrived is that Steven Spielberg is an executive producer on True Grit, and the powerful Scott Rudin the producer. A controversy that just sprang up today is whether or not Hailee Steinfeld should have been nominated as Best Actress or Best Supporting Actress.

D: That’s a kind of Hollywood political thing, isn’t it?

L: Yes.

D: Maybe Scott (Rudin) didn’t think she could win as a Best Actress nominee, she’s so young and an unknown. That’s just speculation on my part, but Scott is a brilliant producer.

L: I think what Scott Rudin said—that the story was about the redemption of Rooster Cogburn as the protagonist—isn’t true. I don’t think Rooster was redeemed. I know he saved Mattie’s life, but then he goes on to kill several people and to fight on the wrong side in the Johnson County War.

D: Which we made a movie about ourselves.

L: Yep, Johnson County War, based on the novel Riders of Judgment by Frederick Manfred.

D: But we don’t find out about Rooster’s future misdeeds in True Grit. The film is a different animal from the novel, a statement you’ve made yourself several times about your own adaptations. So … maybe, just maybe, saving Mattie’s life is enough redemption for Rooster in the Coen brothers’ version of the story. He rode with the scoundrel Quantrill, but that was before Mattie.

L: But it’s left hanging in the movie whether or not Rooster is redeemed.

D: I don’t necessarily agree with that. Maybe I’m not as stern a judge as you, Larry. Rooster said it himself when he said if he felt his life was in danger …

L: … he shot ’em.

D: Exactly. A person would be hard pressed to know how they’d react in the same situation. Do you think either Gus or Call redeemed themselves in Lonesome Dove?

L: Gosh, I’ll have to think about that … not particularly, no.

D: Jeff Bridges said that the Coen brothers wore cowboy hats to the set every day.

L: Does this mean they thought they were making a western?

D: In their interview with the Guardian, Joel and Ethan gave the journalist the impression that, “To hear the Coens tell it, their True Grit may not even be a western.”

L: Yes, they likened it more to Alice in Wonderland. I think they’re right. Mattie goes across the river, to a place she’s never been before, where she sees all these things.

D: Alice in Wonderland and The Wizard of Oz are pretty highfalutin company for True Grit. It’s likely thought of as a western because it’s a period piece with horses and guns, though it takes place in Arkansas. But they do drift across the river into Indian territory, which is part of the west, correct?

L: Just barely. The Oklahoma Panhandle may be part of the west, I suppose. There were borrowings from plenty of westerns, like the final shootout between Rooster and Ned Pepper.

D: And the landscape is more true to place in the Coen brothers version than in the 1969 film.

L: The terrain bothered me in the 1969 version. That landscape looked like Colorado.

D: No wonder it bothers you. It was shot in Colorado.

L: I wondered where all those mountains came from. The business about Rooster holding the reins between his teeth came from Quantrill. Quantrill did it.

D: I didn’t know that.

L: I didn’t know it until today when I read the afterword in the paperback.

D: I agree with Donna Tartt about the scene where Rooster pulls his gun on La Boeuf while the latter is spanking Mattie. That’s when I knew Rooster would always side with the girl.

L: I thought that scene was silly in both versions of the film. I didn’t believe it.

D: Silly? Why on earth would you think it silly?

L: Why would La Boeuf suddenly spank a fourteen-year-old girl?

D: Because he likes her. In the way that boys like girls. Fourteen was a marrying age back then. It’s a kind of flirtation.

Advertisement

L: I didn’t believe Rooster would shoot him.

D: Maybe, maybe not, but La Boeuf’s certainly getting a little too familiar with Mattie. Rooster doesn’t like it, pulls his gun, and La Boeuf backs off.

L: I wish both films had left out the character that gobbled.

D: You mean the imbecile.

L: Yes, it’s a cliché. There are too many films where a character gobbles.

D: What films?

L: The most surprising performance in both films was Glen Campbell in the 1969 version. A better La Boeuf than Matt Damon, who seemed rather flat and stiff to me.

D: Glen Campbell was certainly livelier. What struck me was the physical resemblance between Matt Damon and Glen Campbell. We both laughed when we realized that, remember? Elvis was even offered the role of La Boeuf. Colonel Parker, Elvis’s manager, wanted him to have top billing over John Wayne, which would have never worked. Henry Hathaway said he hated Glen Campbell’s performance, which he described as wooden.

L: That shows how much Henry Hathaway knew. To my thinking, the original version of True Grit was flat as a corn cake until John Wayne showed up on the screen. And Glen Campbell’s performance was graceful.

D: I have to agree with you. He was incredibly charming.

L: You said it yourself, “Here comes the Duke, now the movie’s alive.” The Duke knew how to sit on a horse.

D: Speaking of horses, I thought in both films that seeing Mattie’s beloved horse Little Blackie run to death was too painful.

L: I agree. No fun watching a fine horse run to death.

D: You know, John Wayne didn’t like the finished film. Didn’t he tell Richard Burton on Oscar night that Burton should have won the Oscar instead of him?

L: For Anne of a Thousand Days, yes.

D: What a difference between Jeff Bridges’s performance and John Wayne’s. Jeff’s was more thoughtful …

L: … and Wayne’s was more raw force. What I think of as a great western, Sam Peckinpah’s The Wild Bunch, was released one week after the 1969 True Grit.

D: The Wild Bunch was like Sergio Leone with dialogue.

L: The music was Sergio Leone music.

L: There were certainly compelling performances. William Holden, for example.

D: And Warren Oates.

L: I seem to be one of the few people not wowed by True Grit the novel.

D: Very little fiction wows you anymore.

L: That’s true. It’s not Tolstoy. It’s not Faulkner.

D: It doesn’t claim to be. It’s just good old-fashioned storytelling. I enjoyed it. I felt like I was thirteen years old again reading that novel.

L: I liked how Mattie used a Sharps rifle to shoot Tom Chaney in the new movie.

D: The Sharps kick is much more believable than the pistol kick in the first fiim.

L: Did you know that the Coen brothers used the f-word 260 times in The Big Lebowski? A shocking thing for two nice Jewish boys from Minnesota to have done.

D: No, and that sounds like something you’d remember. Actually, the success of their fourteen-film opus seems to shock the Coens a bit.

L: My favorite scene in the John Wayne version is when Rooster clobbers La Boeuf with his rifle.

D: You laughed out loud at that scene. In Hathaway’s version, Rooster certainly had the best lines. My two favorite lines in the Coen brothers were when Mattie says, “My mother’s indecisive and hobbled by grief,” and when Rooster says, “I’m a foolish old man who’s been drawn into a wild goose chase by a harpie in trousers and a nincompoop.”

L: My favorite lines in modern cinema are from The Big Lebowski: Tara Reid’s character says, “I’ll suck your cock for a thousand dollars.” And The Dude (Jeff Bridges) replies, “I’m just gonna go find a cash machine.”

D: Well, I love that quote attributed to John Wayne: “Life is tough, but it’s tougher if you’re stupid.”