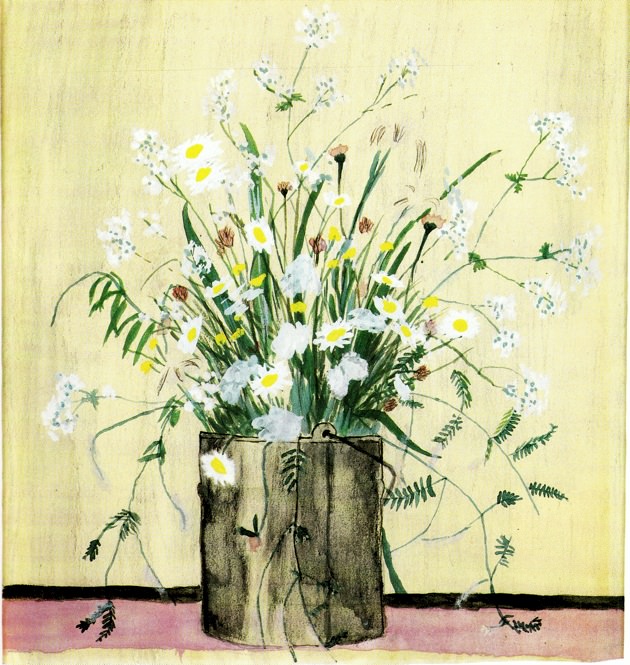

Collection of Loren MacIver

Elizabeth Bishop: Daisies in Paintbucket. Watercolor and gouache, 10½ x 9½ inches. Used as the jacket illustration for One Art: Letters. The lyrical, semi-abstract array of flowers–in short strokes and freely drawn delicate lines–fans out over the paint bucket, which is placed dead center and as far front as possible. It has the aplomb of a masterpiece.

This year is the centenary of the birth of Elizabeth Bishop, one of the most celebrated figures in American poetry, and several new collections of her prose, poems, and correspondence have been published to commemorate it. Her work is a widely recognized force in American poetry. Far less known is that Bishop was also an accomplished artist.

Throughout her life, she collected art and wrote about it in poems, letters, and stories. Many of her friends were artists. She owned a Calder mobile and bought a collage by Kurt Schwitters for Lota, her Brazilian partner. She made “boxes” in homage to the sculptor Joseph Cornell, and the title of her painting E. Bishop’s Patented Slot Machine is a reference to his work. The original editions of The Complete Poems, The Collected Prose, and One Art (her collected letters) all have covers taken from her pictures. With characteristic self-effacement, Bishop scarcely acknowledged herself as an artist—and yet her work, mostly watercolor and gouache, reveals a keen and original sensibility.

The style of Bishop’s painting is a style she settled on. One proof of this is that we have no transitional examples, no works that exhibit the obvious tendencies of a beginner, like trying out ways to turn the form. (It’s worth observing, in the case of Calder, Schwitters, and Cornell, that none of the art of these three major figures, for which she felt an affinity, depends in any overt way on conventional draftsmanship or painting ability.) George Bataille writes somewhere, “Realism gives me the impression of a mistake.” Rendering skills are not difficult to come by; most students begin unlearning them their first year of art school. But importantly, modernism itself was for Bishop and others of her generation the heroic model of that unlearning; a profound impatience with an outdated diction produced Matisse and Picasso—as well as William Carlos Williams.

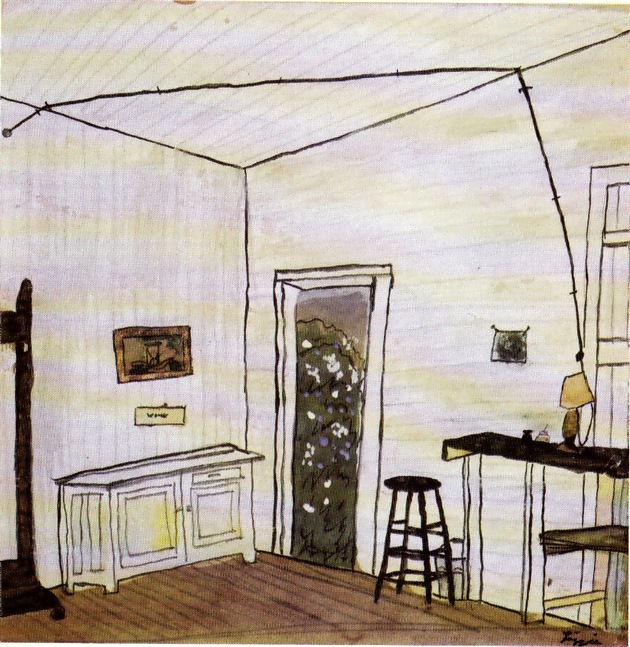

Collection of Loren MacIver

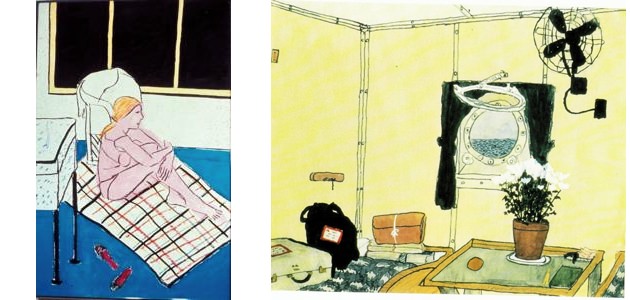

Elizabeth Bishop: Interior With Extension Cord. Watercolor, gouache, and ink, 6 x 6 inches. The general rule of a Bishop picture is: If a table exists, put flowers on it. In this case, with the dramatic focus on the extension cord crossing the planes of the white room (to bring a lamp to the narrow working space), she simply opened the door to the garden instead.

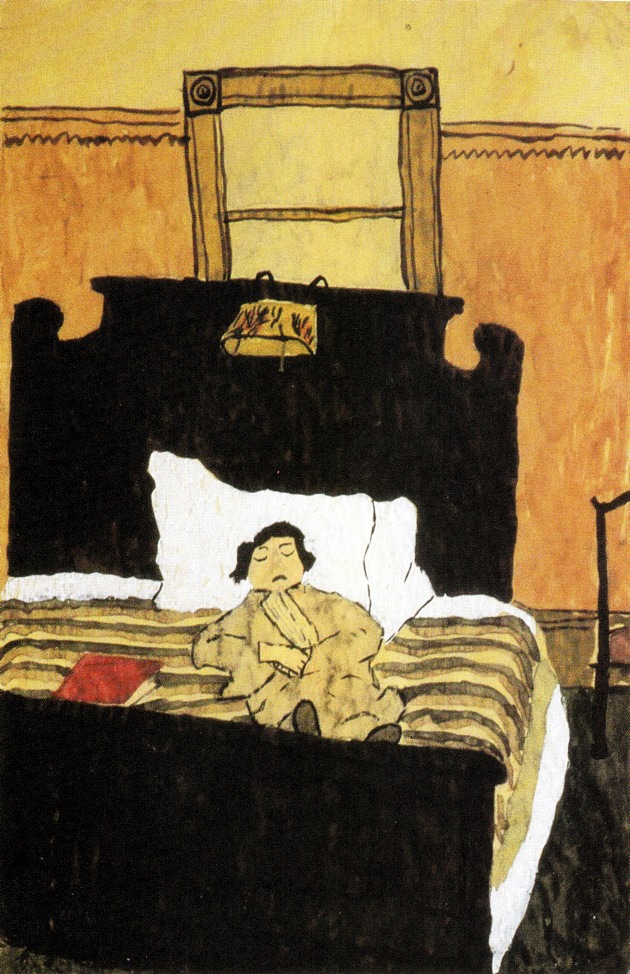

Thus, the coherence of Bishop’s pictures supersedes a constraint to “get the nose right.” In early pictures dating from the thirties and forties, such as Sleeping Figure and Interior with Extension Cord, she clearly understands that value lies less in precise replication than in a personal system of marking. As she observes in “Poem,” from Geography III:

In the foreground

a water meadow with some tiny cows,

two brushstrokes each, but confidently cows.

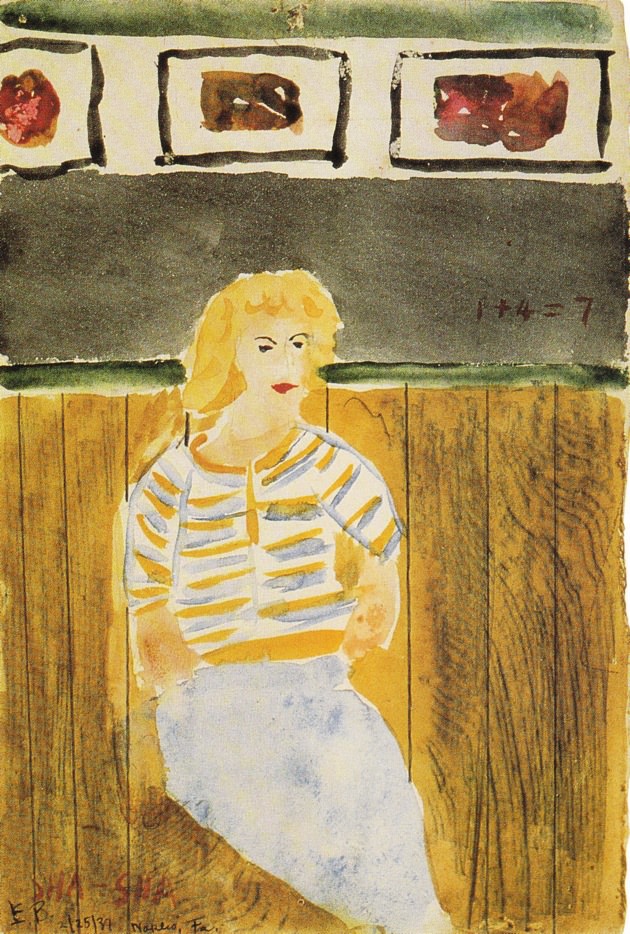

In Sha Sha, an early portrait of her friend Charlotte Russell, above the wainscoting panels whose wood grain, complete with mildew, receives special attention, a simple mathematical equation is written on the wall: “1 + 4 = 7.” As perhaps a comment on other “inaccuracies” in the picture—the anatomy of the figure, the invisible chair she sits on—it boasts, like them, a pictorial rightness of its own.

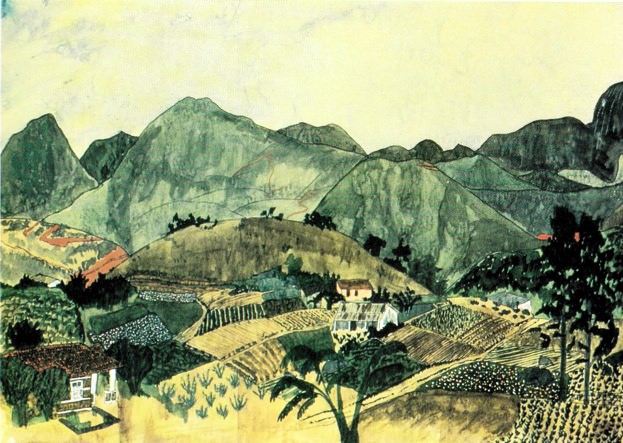

Only about forty of Bishop’s paintings have survived. Her influences were diverse. She liked Édouard Vuillard, Jules Bissiers, Oskar Kokoshka. Paul Klee, who worked small, in an ersatz primitive style, was a major influence. She once wrote to James Merrill about flying over the Andes: “You’ll see how exactly like some of Klee’s paintings they look.” Her picture Brazilian Landscape, a view from the back porch of Samambaia, the house in Petropolis where she and Lota lived from 1951 to 1967, was sent to a friend with the comment, “…it’s big enough so that if you like any section of it you can cut that part out.” This is an example of her famous modesty—but also perhaps a subtle allusion to her use of Klee’s compositional grids, built up out of discrete sections.

Bishop is fluent within her powers. Nothing is tentative—the line may wobble, but it rules. In pictures like Harris School, The Armory, and Daisies in Paint Bucket, done in Key West where she lived from 1938 to 1942, the composition is bold and frontal, with deft touches like the small black-and-white abstraction of a sign on a building, or gray washes that evoke the shiny surface of a paint bucket as well as a band of glue residue left from a peeled-off label. In “Olivia,” with visual wit she adds to a run down church a leaning steeple made of power lines and “heaven.”

Advertisement

By the time modernism reached its saturation point in mid-century, with Pollock leading the graduating class of New York’s Cedar Tavern into imminent glory, Bishop was living in Brazil. The fact that she was somewhere other than New York for one of the defining eras in the history of American art, rhymes quietly with the habits and predilections of her life. The huge canvases and vivid, autobiographical swagger of Abstract Expressionism would have been at odds with her own impulses.

Bishop’s paintings have much more in common with the work of a later generation of artists, who found in the post-modernism of the sixties and seventies the possibility of new ways of returning to figurative art. Bishop’s remarkable Porthole, from the 1950s, is similar enough to Celeste #3, painted some twenty years later by the young Bay Area artist Joan Brown, that the two works could be sequential frames in a graphic novel. Tired of sitting around the apartment, a young woman packs her bags and catches the first boat to Rio.

Bishop enjoyed being innovative and invisible at the same time. As a painter, she discovered in the limited range of her skills an intrinsic value. To see it made it so. Meyer Shapiro, the distinguished art critic, said she “writes poems with a painter’s eye.” From “The Man-Moth” to “The Moose,” the deceptive conventionality of Bishop’s poetry is part of what makes it so original, and even subversive. She was the fascinating outsider at the masked ball in a company of congenial, if often over-bred, bores. She opened and admired their jeweled music boxes and, with the real daring of upward mobility, let herself be mistaken for one of them—by herself even. Hence that half-modest, half-elitist lilt when she protests that her paintings are, “…Not Art—NOT AT ALL.”

Her pictures, the way we know of them almost as much as what they are, place us to some extent in a position of reckoning their virtues beyond the guideposts of objective categories. Yet, at a certain point in looking at art, categories become useless. Bishop’s paintings put a value on the unrehearsed oneness of experience. The elusive strength of her poetry, for all its polish and refinement, does the same.

The sun set in the sea; the same odd sun

rose from the sea,

and there was one of it and one of me.

(From “Crusoe in England,” Geography III)

William Benton is the editor of Exchanging Hats, a book of Elizabeth Bishop’s paintings, and author most recently of Madly, a novel.