To be exiled is not to disappear but to shrink, to slowly or quickly get smaller and smaller until we reach our real height, the true height of the self. Swift, master of exile, knew this. For him exile was the secret word for journey. Many of the exiled, freighted with more suffering than reasons to leave, would reject this statement.

All literature carries exile within it, whether the writer has had to pick up and go at the age of twenty or has never left home.

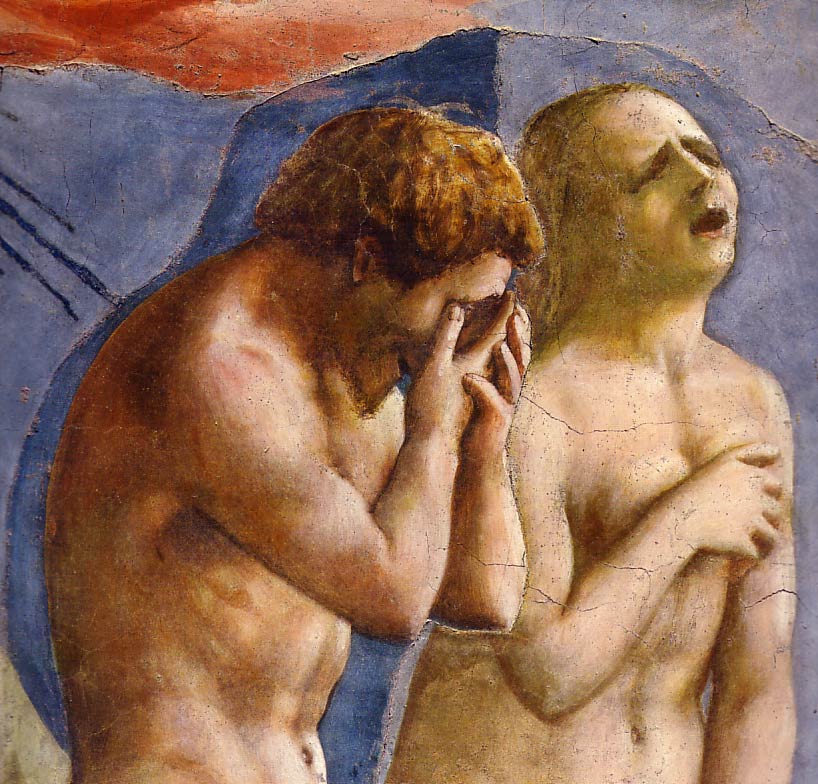

Probably the first exiles on record were Adam and Eve. This is indisputable and it raises a few questions: can it be that we’re all exiles? Is it possible that all of us are wandering strange lands?

The concept of “strange lands” (like that of “home ground”) has some holes in it, presents new questions. Are “strange lands” an objective geographic reality, or a mental construct in constant flux?

Let’s recall Alonso de Ercilla.

After a few trips through Europe, Ercilla, soldier and nobleman, travels to Chile and fights the Araucanians under Alderete. In 1561, when he’s not yet thirty, he returns and settles in Madrid. Twenty years later he publishes La Araucana, the best epic poem of his age, in which he relates the clash between Araucanians and Spaniards, with clear sympathy for the former. Was Ercilla in exile during his American ramblings through the lands of Chile and Peru? Or did he feel exiled when he returned to court, and is La Araucana the fruit of that morbus melancholicus, of his keen awareness of a kingdom lost? And if this is so, which I can’t say for sure, what has Ercilla lost in 1589, just five years before his death, but youth? And with his youth, the arduous journeys, the human experience of being exposed to the elements of an enormous and unknown continent, the long rides on horseback, the skirmishes with the Indians, the battles, the shadows of Lautaro and Caupolicán that, as time passes, loom large and speak to him, to Ercilla, the only poet and the only survivor of something that, when set down on paper, will be a poem, but that in the memory of the old poet is just a life or many lives, which amounts to the same thing.

And what is Ercilla left with before he writes La Araucana and dies? Ercilla is left with something—if in its most extreme and bizarre form—that all great poets possess. He’s left with courage. A courage worth nothing in old age, just as, incidentally, it’s worth nothing in youth, but that keeps poets from throwing themselves off a cliff or shooting themselves in the head, and that, in the presence of a blank page, serves the humble purpose of writing.

Exile is courage. True exile is the true measure of each writer.

At this point I should say that at least where literature is concerned, I don’t believe in exile. Exile is a question of tastes, personalities, likes, dislikes. For some writers exile means leaving the family home; for others, leaving the childhood town or city; for others, more radically, growing up. There are exiles that last a lifetime and others that last a weekend. Bartleby, who prefers not to, is an absolute exile, an alien on planet Earth. Melville, who was always leaving, didn’t experience—or wasn’t adversely affected by—the chilliness of the word exile. Philip K. Dick knew better than anyone how to recognize the disturbances of exile. William Burroughs was the incarnation of every one of those disturbances.

Probably all of us, writers and readers alike, set out into exile, or at least a certain kind of exile, when we leave childhood behind. Which would lead to the conclusion that the exiled person or the category of exile doesn’t exist, especially in regards to literature. The immigrant, the nomad, the traveler, the sleepwalker all exist, but not the exile, since every writer becomes an exile simply by venturing into literature, and every reader becomes an exile simply by opening a book.

Almost all Chilean writers, at some point in their lives, have gone into exile. Many have been followed doggedly by the ghost of Chile, have been caught and returned to the fold. Others have managed to shake the ghost and gone into hiding; still others have changed their names and their ways and Chile has luckily forgotten them.

When I was fifteen, in 1968, I left Chile for Mexico. For me, back then, Mexico City was like the Border, that vast nonexistent territory where freedom and metamorphosis are common currency.

Despite it all, the shadow of my native land wasn’t erased and in the depths of my stupid heart the certainty persisted that it was there that my destiny lay.

Advertisement

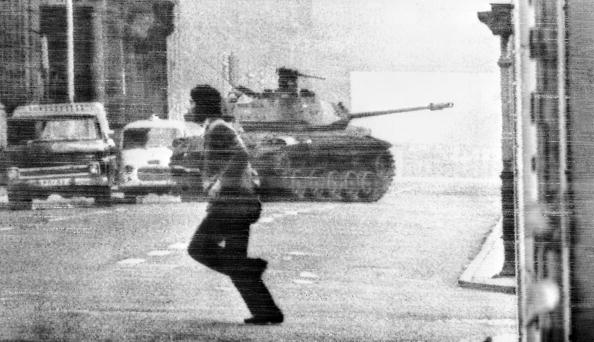

I returned to Chile when I was twenty to take part in the Revolution, with such bad luck that a few days after I got to Santiago the coup came and the army seized power. My trip to Chile was long, and sometimes I’ve thought that if I’d spent more time in Honduras, for example, or waited a little before shipping out from Panama, the coup would’ve come before I got to Chile and my fate would have been different.

In any case, and despite the collective misfortunes and my small personal misfortunes, I remember the days after the coup as full days, crammed with energy, crammed with eroticism, days and nights in which anything could happen. There’s no way I’d wish a twentieth year like that on my son, but I should also acknowledge that it was an unforgettable year. The experience of love, black humor, friendship, prison, and the threat of death were condensed into no more than five interminable months that I lived in a state of amazement and urgency. During that time, I wrote one poem, which wasn’t just bad like the other poems I wrote back then, but excruciatingly bad. When those five months were up I left Chile again and I haven’t been back since.

That was the beginning of my exile, or what is commonly known as exile, although the truth is I didn’t see it that way.

Sometimes exile simply means that Chileans tell me I talk like a Spaniard, Mexicans tell me I talk like a Chilean, and Spaniards tell me I talk like an Argentinean: it’s a question of accents.

The fates chosen by those who go into exile are often strange. After the Chilean coup in 1973, I remember that few political refugees made their way to the embassies of Bulgaria or Romania, for example, with France or Italy preferred by many, although as I recall, top honors went to Mexico, and also Sweden, two very different countries that in the Chilean collective unconscious must have stood for two opposite manifestations of desire, although it’s true that in time the balance tilted toward the Mexican side and many of those who went into exile in Sweden began to turn up in Mexico. Many others, however, remained in Stockholm or Göteborg, and when I was living in Spain I ran into them every summer on vacation, speaking a Spanish that to me, at least, was startling, because it was the Spanish that was spoken in Chile in 1973, and that now is spoken nowhere but in Sweden.

Exile, in most cases, is a voluntary decision. No one forced Thomas Mann to go into exile. No one forced James Joyce to go into exile. Back in Joyce’s day, the Irish probably couldn’t have cared less whether he stayed in Dublin or left, whether he became a priest or killed himself. In the best of cases, exile is a literary option, similar to the option of writing. No one forces you to write. The writer enters the labyrinth voluntarily—for many reasons, of course: because he doesn’t want to die, because he wants to be loved, etc.—but he isn’t forced into it. In the final instance he’s no more forced than a politician is forced into politics or a lawyer is forced into law school. With the great advantage for the writer that the lawyer or politician, outside his country of origin, tends to flounder like a fish out of water, at least for a while. Whereas a writer outside his native country seems to grow wings. The same thing applies to other situations. What does a politician do in prison? What does a lawyer do in the hospital? Anything but work. What, on the other hand, does a writer do in prison or in the hospital? He works. Sometimes he even works a lot. And that’s not even to mention poets. Of course the claim can be made that in prison the libraries are no good and that in hospitals there are often are no libraries. It can be argued that in most cases exile means the loss of the writer’s books, among other material losses, and in some cases even the loss of his papers, unfinished manuscripts, projects, letters. It doesn’t matter. Better to lose manuscripts than to lose your life. In any case, the point is that the writer works wherever he is, even while he sleeps, which isn’t true of those in other professions. Actors, it can be said, are always working, but it isn’t the same: the writer writes and is conscious of writing, whereas the actor, under great duress, only howls. Policemen are always policemen, but that isn’t the same either, because it’s one thing to be and another to work. The writer is and works in any situation. The policeman only is. The same is true of the professional assassin, the soldier, the banker. Whores, perhaps, come closest in the exercise of their profession to the practice of literature.

Advertisement

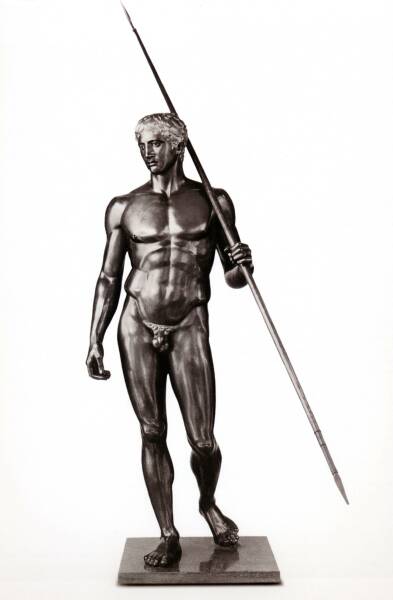

Archilochus, Greek poet of the seventh century BC, is a perfect example of this phenomenon. Born on the island of Paros, he was a mercenary, and, according to legend, he died in combat. We can imagine his life spent wandering the cities of Greece.

In one fragment, Archilochus doesn’t hesitate to admit that in the midst of battle, probably a skirmish, he drops his arms and goes running, which for the Greeks was undoubtedly the greatest mark of shame, let alone for a soldier who has to earn his daily bread by his courage in combat. Archilochus says:

Some Saian mountaineer

Struts today with my shield.

I threw it down behind a bush and ran

When the fighting got hot.

Life seemed somehow more precious.

It was a beautiful shield.

I know where I can buy another

Exactly like it, just as round.

And classical scholar Carlos García Gual on Archilochus: he had to leave the island where he was born to earn a living with his lance, as a soldier of fortune. He knew war only as a toilsome chore, not as a field of heroic deeds. He won renown for his cynicism in a few lines of verse that tell how he flees the battlefield after he throws away his shield. His openness in confessing such a shameful act is striking. (In hoplite tactics, the shield is the weapon that protects the flank of the next soldier, symbol of courage, something never to be lost. “Return with the shield or on the shield,” it was said in Sparta.) All the pragmatic poet cared about was saving his own life. He cared nothing for glory or the code of honor.

Another fragment: “Hang iambics. / This is no time / for poetry.” And: “Father Zeus, / I’ve had / No wedding feast.” And: “His mane the infantry / cropped down to stubble” And: “Balanced on the keen edge / Now of the wind’s sword, / Now of the wave’s blade.” And this, which could only have been written by someone buffeted by fate:

Attribute all to the gods.

They pick a man up,

Stretched on the black loam,

And set him on his two feet,

Firm, and then again

Shake solid men until

They fall backward

Into the worst of luck,

Wandering hungry,

Wild of mind.

And this, spotlessly cruel and clear:

Seven of the enemy

were cut down in that encounter

And a thousand of us,

mark you,

Ran them through.

And:

Soul, soul,

Torn by perplexity,

On your feet now!

Throw forward your chest

To the enemy;

Keep close in the attack;

Move back not an inch.

But never crow in victory,

Nor mope hangdog in loss.

Overdo neither sorrow nor joy:

A measured motion governs man.

And this, sad and pragmatic:

The heart of mortal man,

Glaukos, son of Leptines,

Is what Zeus makes it,

Day after day,

And what the world makes it,

That passes before our eyes.

And this, in which the human condition shines:

Hear me here,

Hugging your knees,

Hephaistos Lord.

My battle mate,

My good luck be;

That famous grace

Be my grace too.

And this, in which Archilochus gives us a portrait of himself and then vanishes into immortality, an immortality in which he didn’t happen to believe: “My ash spear is my barley bread, / My ash spear is my Ismarian wine. / I lean on my spear and drink.”

This essay is drawn from Between Parentheses: Essays, Articles and Speeches (1998–2003) by Roberto Bolaño, translated by Natasha Wimmer, forthcoming from New Directions on May 30. All translations from Archilochus are by Guy Davenport, from Archilochus, Sappho, Alkman: Three Lyric Poets of the Late Greek Bronze Age (University of California Press, 1980).