When I was a boy I read, in a biography of Daniel Boone, or of Daniel Beard, that young Dan (whichever of the two it may have been—or maybe it was young George Washington) had so loved some book, had felt his heart and mind inscribed so deeply in its every line, that he had pricked his fingertip with a knife and, using a pen nib and his blood for ink, penned his name on the flyleaf. At once, reading that, I knew two things: 1) I must at once undertake the same procedure and 2) only one, among all the books I adored and treasured, was worthy of such tribute: The Phantom Tollbooth. At that point I had read it at least five or six times.

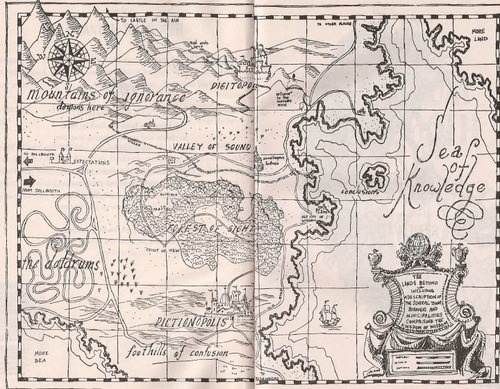

First published in 1961, The Phantom Tollbooth describes the comical-epic journey of Milo, a rather etiolated young fellow awash in grade school ennui who, one day, under mysterious circumstances, finds himself in receipt of a package containing the eponymous tollbooth. Mildly curious—a strong emotion for mild Milo—he climbs into his battery-powered toy car and rolls through the tollbooth, duly paying his fare, and finds himself on the outermost outskirts of the Kingdom of Wisdom. Milo’s journey, at first undertaken with a shrug, transforms itself into a quest, one that takes him from Expectations, through Dictionopolis, Digitopolis, and the Mountains of Ignorance, to the Castle in the Air, where a pair of princesses, Rhyme and Reason, languish in captivity. Clearly the geography and topography of the Kingdom of Wisdom, like the plot of the novel, emit a powerful whiff of the allegorical; yet somehow, through the wit and artistry and recursive playfulness of its author, Norton Juster, The Phantom Tollbooth manages to surmount the insurmountable obstacle that allegory ordinarily presents to pleasure.

The book appeared in my life as mysteriously as the titular tollbooth itself, brought to our house one night as a gift for me by some old friend of my father’s whom I had never met before, and never saw again. Maybe all wondrous books appear in our lives the way Milo’s tollbooth appears, an inexplicable gift, cast up by some curious chance that comes to feel, after we have finished and fallen in love with the book, like the workings of a secret purpose. Of all the enchantments of beloved books the most mysterious—the most phantasmal—is the way they always seem to come our way precisely when we need them.

This was, I’m guessing, somewhere around 1971 (as long ago now as the days of zeppelins, iron lungs, and Orphan Annie were to me then, at eight years old). I was not as discontented with or disappointed by life as Milo (not yet), and I can remember feeling a faint initial disapproval of the book’s mopey young protagonist the first time I read it. Life and the world still held considerable novelty and mystery for me at that time, even when strongly flavored with routine. It was hard for me to sympathize with Milo, wanting to be home when he was at school and at school when he was home. The only place I ever truly longed to be that was not where I happened to find myself (not counting dentists’ chairs and Saturday morning synagogue services) was inside the pages of a book. And here, again, as I found on finishing the novel, The Phantom Tollbooth understood me.

Milo’s journey into the Lands Beyond (beyond the flyleaf, that is, with its spectacular Jules Feiffer map), was mine as a reader, and my journey was his, and ours was the journey of all readers venturing into wonderful books, into a world made entirely, like Juster’s, of language, by language, about language. While you were there, everything seemed fraught and new and notable, and when you returned, even if you didn’t suffer from Milovian ennui, the “real world” seemed deeper, richer, at once explained and, paradoxically, more mysterious than ever. On his return from the Kingdom of Wisdom, Milo looks outside his window and finds that

there was so much to see, and hear, and touch—walks to take, hills to climb, caterpillars to watch as they strolled through the garden […] And, in the very room in which he sat, there were books that could take you anywhere, and things to invent, and make, and build, and break, and all the puzzle and excitement of everything he didn’t know—music to play, songs to sing, and worlds to imagine and then someday make real.

I had wanted, carrying my sugar pills and plastic stethoscope around in a plastic black bag, to be a doctor, and then, feeling the first pangs of world-making hunger, an architect. It was while reading The Phantom Tollbooth that I began to realize, not that I wanted to be a writer (that came a little later, at the mercy of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle), but something simpler: I had a crush on the English language, one that was every bit as intense, if less advanced, as that from which the augustly named author, Mr. Norton Juster, himself evidently suffered.

Advertisement

I am the son and grandson of helpless, hardcore, inveterate punsters, and when I got to Milo getting lost in The Doldrums where he found a (strictly analog) watchdog named Tock, it was probably already too late for me. I was gone on the book, riddled like a body in a crossfire by its ceaseless barrage of wordplay—the arbitrary and diminutive apparatchik, Short Shrift; the kindly and feckless witch, Faintly Macabre; the posturing Humbug, and, of course, the Island of Conclusions, reachable only by jumping. Puns—the word’s origin, like the name of some pagan god, remains unexplained by etymologists—are derided, booed, apologized for.

When my father and grandfather committed acts of punmanship they were often, generally by the women at the table or in the car with them, begged if not ordered to cease at once. “Every time I see you,” my grandfather liked to tell me, grinning, during the days of my growth spurt, “you grusomer!” Maybe puns are a guy thing; I don’t know. I can’t see how anybody who claims to love language can fail to marvel at the beautiful slipperiness of meaning that puns, like aquarium nets, momentarily catch and bring shimmering to the surface. Puns act to shatter or at least compromise meaning; a pun condenses unrelated, even opposing meanings, like a collapsing dwarf star, into a singularity. Maybe it’s this antisemantic vandalism that leads so many people to shun and revile them.

And yet I would argue—and it’s a lesson I learned first from my grandfather and father and then in the pages of The Phantom Tollbooth—that puns, in fact, operate to generate new meanings, outside and beyond themselves. Anyone who jumps to conclusions, as to the island of Conclusions, is liable to find himself isolated, alone, unable to reconnect easily with the former texture and personages of his life. Without the punning island first charted by Norton Juster, we might not understand the full importance of maintaining a cautionary distance toward the act of jumping to conclusions, as Mr. Juster implicitly recommends.

But it was not just the puns and wordplay that gave me a bad case of loving English. It was the words themselves: the vocabulary of the book. I can still, forty years later, remember my first encounters with the following words: macabre, din, dodecahedron, discord, trivium, lethargy. They are all, capitalized and adapted, characters in the novel. Entire phrases, too, found their way into the marbles-sack of my eight-year-old word-hoard: “rhyme and reason,” “easy as falling off a log,” “taking the words right out of your mouth.” To this day when I happen to write those or any other of the words that I remember having first seen in The Phantom Tollbooth, I get a tiny thrill of nostalgia and affection for the wonderful book, and for its author, and for myself when young, and for the world I then lived in. A world of wonders, but not so replete that it could not be improved upon, perhaps even healed, by a journey like Milo’s, through a book. But if you’ve read the book, you probably know what I’m talking about. If you haven’t, what are you waiting for? Stop reading this nonsense, already, and get on to Chapter 1. I’ll be waiting for you, at the other end, with a pin to prick your fingertip.

This essay is drawn from Michael Chabon’s introduction to a fiftieth anniversary edition of The Phantom Tollbooth that will be published by Knopf in October.