Over Easter weekend, the government of Syrian president Bashar al-Assad launched a brutal crackdown on the peaceful protests that have been gathering force across the country in the last five weeks. Around 120 protesters were killed in several different cities by security forces (bringing the total to some 400 since the protests began); and thousands more were arrested. On April 25, tanks moved to Daraa, the southern city where the protests first began in mid-March, triggered by the arrest and torture of teenagers who had scrawled anti-government graffiti on the city’s walls. Near Damascus, the towns of Douma and Moadamiyeh have been similarly sealed off, as have Baniyas, Homs, Jableh, and Hama, and people I am in contact with tell me that there are soldiers on every street corner in the northwestern port city of Latakia.

In areas where protests have occurred, hospitals were ordered not to treat activists—and some doctors who disobeyed have been arrested. I have also received news that injured protesters are being taken away by police from their hospital beds.

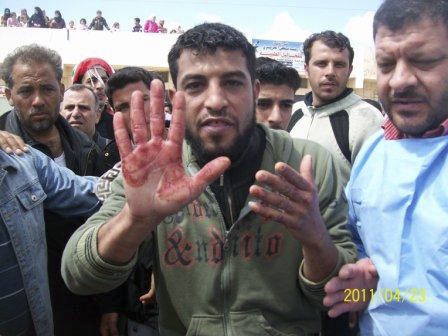

As this fierce response unfolds, checkpoints in protest areas have been set up to search people for mobile phone pictures and footage of the violence. Telephone and Internet networks in Daraa and Douma have been cut, and few people have been able to leave or contact the outside world. There are reports of government snipers firing on pedestrians, and residents no longer dare leave their homes. Rooftop water tanks have also been targeted by snipers in Daraa, where electricity has also been cut off. Foreign journalists, who in recent weeks have been harassed and dissuaded from pursuing their stories (and in a few cases arrested and beaten), have now been expelled.

The dearth of information has raised questions about who is involved in the protests, the breadth of popular support for them, and what prospects they might have—in the face of such repression—to bring about a broader change. While it has been increasingly difficult to get a full picture of the towns and cities where the government has responded with force, some insights can be gained from the situation in Douma, a flash point in the protests, which I was able to visit shortly before the most recent violence.

Often called a suburb of Damascus, Douma is a mostly lower-middle-class town of about 112,000 people struggling with unemployment. There are some doctors, lawyers, and professionals, and students who commute to Damascus University, but most residents are workers and lower-ranking government employees. Those who don’t use the Internet have at least some friends or relations who do, and certainly have access to mobile phones. The younger generation is, of course, more technologically savvy; many know how to keep in touch with people in and outside Syria, and therefore have taken the lead in the protests. Demonstrations began early on in Douma, both in solidarity with the people of Daraa, and because its residents had similar grievances against the Syrian government’s political corruption and oppressive security state.

Indeed, while they do not seem to have a clearly defined leadership, protesters around the country have from the outset been united in their broad aim of political reform; there was actually a small demonstration in central Damascus as early as March 15, though it was quickly dispersed by the government. The specific and more immediate demands include: the lifting of emergency law; the release of political prisoners; the right to form new political parties and to protest peacefully; the right of freedom of speech and of the media; an end to corruption; permission to exiled dissidents to return to Syria; and the bringing to justice of those responsible for killing, arresting or torturing protesters and political opponents. There were, initially, a few immediate economic requests, such as the implementation of measures to reduce unemployment and high prices, and salary increases for civil servants, but activists recently drew up some more long-term demands regarding the restructuring of political, security, and judicial institutions.

Tension was extremely high on the day I visited; protests had already been taking place for nearly three weeks and fourterrn protesters had just been shot by the government’s security forces. Those killings occurred at the end of a major Friday protest in Douma’s central square. One resident told me that the protest had been a response to Assad’s televised address to the nation two days earlier—his first since demonstrations began. The president appeared far removed from his people and surrounded by congratulatory members of parliament who theatrically interrupted his speech every now and then to pay him tributes. Rather than apologizing for the deaths that had already occurred, Assad blamed “terrorists,” “armed gangs,” and “foreign conspirators” for the demonstrations, and promised reforms in his own time and on his terms—hardly a concession.

Advertisement

The protest drew many residents of Douma and continued into the night. One of them told me that the protesters wanted to start a long-term sit-in, so they remained in the central square even though they were asked to leave. The mayor, acting as an intermediary, asked them to make their demands and disperse, promising to forward these demands to the authorities. But this eyewitness said that security forces began to fire before the exchange was completed, and it was a colonel who fired first, giving the signal to the others to start shooting.

Another young man—I’ll call him “Alaa”—watched the protest from the periphery of the square and said that he had seen five members of the moukhabarat (secret police) in civilian clothes pass by on the street under his home. He recognized them as moukhabarat because they all had identical russiyyeh (Kalashnikovs), which they started firing indiscriminately at people. After the shootings, security forces surrounded the city and closed it off to cars and journalists. Phone and Internet networks were also shut down (the official explanation was that there were technical problems caused by a special offer of an hour’s free talk time).

I came to Douma from Damascus with a friend on the day of the burials of the dead protesters. Our nervous taxi driver dropped us outside the city center, and we walked into the central square, where the funerals were taking place. Several thousand people had gathered to pay their respects outside the main mosque.

“Today is the martyrs’ wedding,” someone bellowed through a megaphone to the crowd, which filled the square and spilled out into surrounding streets. The names of the dead were read out. There were eight from Douma and six more from nearby towns and villages; their ages ranged from nineteen to thirty-nine. The voice on the megaphone called for freedom and for the release of political prisoners. The crowd cheered and shouted in response. “Hurriya!” (Freedom!), they repeated, but stopped short of calling for the overthrow of the Assad government. I stood for a while next to some women who were gathered together among the mostly male protesters, a couple of them carrying children. They were dressed in black, some with their faces—as well as their hair—fully covered; a somber group, mourning their dead, not interested in talking to me.

Syria is known for its complicated sectarian mix. The Assad government and ruling Baath party are run by Alawites, a Shia sect followed by around 12 percent of the population. The majority of Syrians are Sunnis, but there are also Christians of all denominations (10 percent), other Shia, Druze, and a tiny Jewish minority. In recent weeks, the government has cited the threat of Islamist extremism as a reason to crack down on protesters. However, despite the veils and niqabs I encountered, there was little evidence in Douma of either an Islamist or sectarian element to the political demands being made.

“We don’t have Ikhwan (Muslim Brotherhood) in Douma,” one man told us. “They’re just conservative around here.” Later, Alaa said the same thing, explaining that much of the local population belongs to the Hanbali school of Sunni Islam, the most conservative of the four Sunni schools. But there were also Shia and more secular people in the crowd. One young man I met, “Imad,” was secular, university-educated, and worked for a large company. He had been demonstrating alongside laborers wearing dusty clothes and the red and white keffiyeh, and religious conservatives. The diversity was also apparent in the different colored ribbons worn as armbands by the mourners—green for the Shia, red for the Sunni.

In other protest cities, such as Latakia and Baniyas, the demonstrations have been even more mixed, with many Shia and Christians participating. Protests in different parts of the country have generally cut across both religious and ethnic divisions: Ismailis (a Shia sect) in Salamiya near Hama, Kurds in the north, Armenians in Latakia, and Druze in Suweida.

Most people who were out in Douma were gathered in the central square. A few were walking briskly on the surrounding streets; they seemed edgy and on high alert. But the funeral was well organized. At each intersection there were two or three local men, making sure people went in the right direction, keeping a look-out, protecting the routes into the center. At a main artery, residents formed a protective line stretching across the street.

Imad told us that security forces had assured Douma residents they wouldn’t enter the town on their day of mourning. But it was difficult to tell who among the mourner-protesters might belong to the moukhabarat, and the men who lined up across the main road and those who stood guard at street corners suggested that few trusted the government to stay away. “I’m scared just standing here talking to you,” Imad said, his eyes glancing about. “We’re not asking for the overthrow of the regime,” he continued, “we just want freedom and reforms.”

Advertisement

While there has been much speculation about the degree to which the Syrian protests have been guided by Internet activists who are modeling their movement on the Tunisian and Egyptian revolutions, it became clear during my visit to Douma that these activists are also driven by the situation on the ground and by the grievances held by protesters against their government.

They are not only calling for basic civil rights, but are also deeply angered by the authorities’ lack of respect for their dignity and honor. In Daraa, for instance, people were incensed by the treatment of their teenagers, by the killing of protesters, and then by attacks on mourners at their funerals. But as in Douma and elsewhere, they were already fed up with the corruption and oppression that has long been a feature of political and economic life in Syria.

Imad, Alaa, and the few protesters brave enough to talk to me in Douma had been following the revolutions taking place elsewhere around the Middle East, and wanted Syrian citizens to enjoy some freedom too. Because of the lockdown on communications, the protests in Syria have been less coordinated than in other countries. Still, Syrian Internet activists—most of them located abroad, in Beirut, Amman, London, or Washington—have been collecting mobile phone footage sent by demonstrators, making them available to the international press, and trying to facilitate coordination between protesters in different parts of the country, particularly where telephone and Internet networks are down.

Until now, demonstrations around the country have largely been spontaneous. But Ausama Monajed, a Syrian activist based in London, told me that he believes the protests have been the largest—and the crackdowns most violent—in Daraa and Douma because people there have the most organized leadership, which includes both imams, who have used their religious authority to inspire people, and secular volunteers.

The Easter crackdown in Douma and other cities came a few days after Assad announced the lifting of the 48-year-old emergency law, an unprecedented move that was nevertheless ominously accompanied by warnings that people should stop demonstrating. Assad’s concessions were received skeptically. Activists say that emergency laws will only be replaced by another set of similar laws under a different name, and don’t in any case change the structure of a ruthless police state and the domination of the Baath party. Protesters in many cities went ahead and on Friday, April 22, staged the largest gatherings to date, involving tens of thousands of people in several cities—the protests that set off the deadly government response.

In Douma, the violence began after Friday prayers, when a crowd began marching from the main mosque to the cemetery. According to reports in the international press, when the crowd passed a government building, plain clothes security forces began firing on them and an unknown number were shot. In the town of Barza, similar pro-government violence led an imam at the city’s main mosque to call on security forces to stop shooting on unarmed protesters.

Over the last few days, thousands of troops have been deployed to Daraa and Douma, where there have been further shootings and arrests, and more are heading to other areas. For the moment, the military appears to be supporting the regime, though in recent days there have been reports of defections from certain army units. One activist told me of eyewitness accounts that soldiers who refused to fire on protesters in Daraa last weekend were shot by the fourth battalion, which is led by Maher Assad, Bashar’s brother. While the military has participated in the latest crackdown, some Syrian analysts believe there eventually may be a split between the general army, which consists of Syrians from all backgrounds, and the security and special forces, the most important of which are Maher’s Alawite-dominated Republican Guards and 4th Armored Division.

In Syria’s two principal cities, Damascus and Aleppo, people remain silent or express support for the government. There were protests at Damascus University two weeks ago, but the pervasive presence of security and intelligence agents has dissuaded many who would like to demonstrate from doing so. Life continues there almost as normal, but there are fewer people on the streets than usual, and for the first time since his father’s era, posters of the president are suddenly ubiquitous, revealing the government’s growing sensitivity to its image. Nevertheless, residents in these two cities are closely watching foreign news channels, since state-controlled television reveals only the official story about extremist groups trying to destabilize the country. The prosperous, urban middle classes are keen on stability and reluctant to express political opinions, but one Syrian analyst who has followed the situation in Damascus closely told me that many “are boiling underneath.”

During the presidency of Bashar’s father, Hafez al-Assad, when there were no mobile phone cameras or 24-hour news channels, and neighboring countries weren’t going through momentous upheavals, even large uprisings could be quietly and mercilessly quashed—as occurred in Hama in 1982, when more than 10,000 people were massacred. But times have changed, and the reforms now on offer seem unlikely to satisfy protesters. The more brutal the repression, the more determined those in revolt have become—despite reports of shortages of food and medical supplies in sealed-off areas. And since their demands have been ignored, frustrated protesters are increasingly calling for “the overthrow of the regime.” One activist told me that “as long as there are no changes, protests will continue”.

More demonstrations were set to take place in several cities on Friday, another Day of Rage, but many fear that the crackdown will get far worse before things change.