Less sensationally than in Egypt, a matter of seeming indifference to the international press, the revolution in Tunisia is starting to unravel. Exactly two years have passed since the self-immolation of a fruit-seller in a depressed provincial town spurred Tunisians to topple their authoritarian president, Zeyn al-Abedine Ben Ali-and Arabs in several other dictatorships to launch uprisings of their own. But the mood on the anniversary of that richly symbolic martyrdom is somber, even defeatist. To many Tunisians, the goals that animated the revolution no longer seem within reach.

What were those goals? To move swiftly and in orderly fashion from fifty-five years of homespun dictatorship (following on from four and a half centuries of Ottoman and French colonization) to a popular form of government. To unite Islamists of various stripes, left-wing trade unionists, economic and social liberals, and French-style secularists of the headscarf-banning variety—all without coercion. To correct the historic economic imbalance between the prosperous littoral and the neglected interior. And finally, to find an accommodation between two Tunisian cultures: the first, bucolic, heir to the Mediterranean civilizations whose amphorae litter the country’s archaeological sites; the second, harking to Arabia and Islam—for Tunisia boasts one the oldest places of worship in the Muslim world, the Mosque of Uqba in the holy city of Kairouan, as well as a thriving hard-line Islamic revivalist movement.

Even with efficient and enlightened leadership, these ambitions might seem unattainable—at least not in the space of a few years or even a single generation. And that excellent leadership, alas, is conspicuous by its absence; the coalition government that was elected fourteen months ago is a typical post-revolutionary dog’s dinner of ideals and methods, dominated by politicians with a rich experience of opposing tyranny and none of exercising power. Furthermore, as I discovered on a trip to the country this month, ordinary Tunisians want results that these men and women are failing to provide.

I arrived in the middle of a full-blown crisis. Starting on November 27, the authorities began responding with disproportionate force to a protest by the inhabitants of the provincial town of Siliana, about eighty miles southwest of Tunis, peppering them with lead shot after some rocks were hurled. At least 250 demonstrators were injured, and several reportedly blinded. Boys were shot in the back; journalists also. The police claimed that seventy-two officers were hurt.

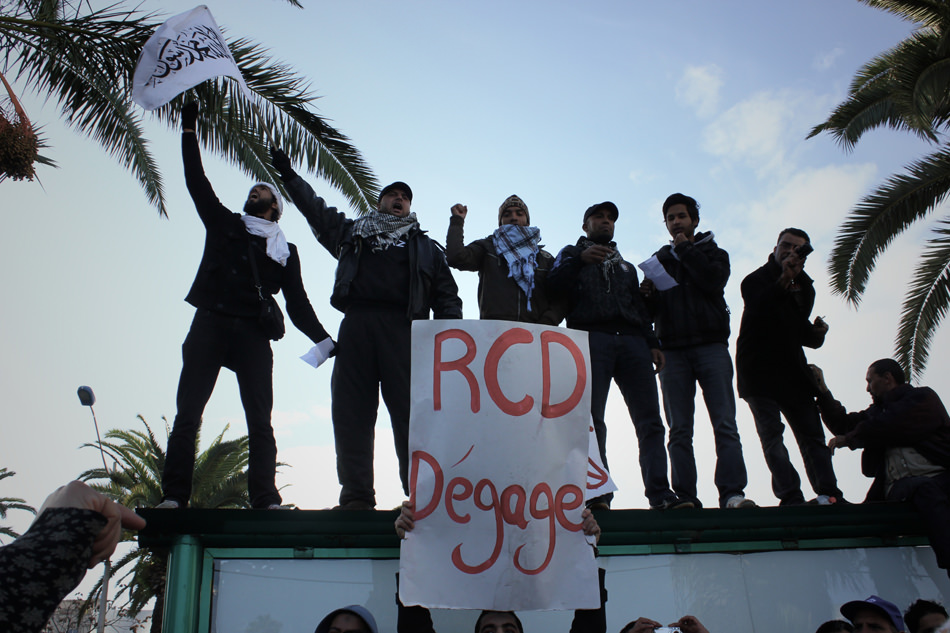

The protesters were demanding the recall of the unpopular provincial governor, justice for some jailed local men, and more investment in their impoverished region. But raising local grievances was also a way of targeting the central government. First in Siliana, then in smaller sympathy protests elsewhere, demonstrators yelled the same pithy injunction, degage! (“Get lost!”) they had directed at Ben Ali in January 2011. Faced with the possibility of wider unrest, the government accepted the protesters’ demands and the agitation stopped five days after it had started.

Visiting Siliana as the town was being cleared up, I was reminded that cynicism and division usually follow the ecstasy of revolution. In the town’s main hospital, men showed me pellets that doctors had extracted from their bodies. “Did we make the revolution for this?” asked one. I suggested that Tunisians now had a constitutional means of registering their displeasure at an underperforming government—elect a different one—and that the provisional government should be given more time to prove itself. The men I spoke to disagreed. They told me that their lives had barely changed since Ben Ali’s departure, and that unemployment was as bad as ever. “We know nothing but humiliation,” another told me. “How can you call yourself a man if you don’t have a job?”

Economic and social deprivation, not a desire for democracy, were the initial causes of the Tunisian revolt. But richer, better-educated Tunisians joined in, and they demanded freedom as well as jobs. The provisional national assembly that emerged from the elections of October 2011 fuelled hopes of improvement in all areas: the changed political order would also bring social justice and economic reform. The new assembly members did not discourage these expectations. They believed that they were finally fulfilling their destiny after years of sacrifice and abasement at the hands of the old regime.

The spirit of solidarity was to be embodied in a coalition government bringing together two parties of the center-left, Ettakol and the Congress for the Republic, under the leadership of the far more powerful Islamist Ennahda (“Renaissance”) Movement. The most important figure in the government is Ennahda’s leader, seventy-one-year-old Rached Ghannouchi, an influential Islamic modernizer whose promotion of democracy in a pious Muslim society has earned him adherents around the world. Having won close to 40 percent of the vote, Ennahda supplied the new prime minister, Hamadi Jebali; the founder of the Congress for the Republic, Moncef Marzouki, was named to the largely ceremonial office of the presidency.

Advertisement

But tensions have risen sharply between the three partners—not least because the divisions between Islamists and secularists that the coalition was designed to bridge, or at least camouflage, are now obvious. An attack on the US Embassy in Tunis during the international furor in September over the US-made film disparaging the Prophet Muhammad, The Innocence of Muslims, led to the deaths of four people and the jailing of scores of Salafists. And increasingly, secularists and religious conservatives have been drawn into a vigorous culture war, in which the former invoke human rights, and the latter, Islamic law. Arguments rage over individuals wearing religious garb in public spaces, art that disparages Islam, or magazines with a bare breast on the cover. Demonstrations are held; threats and counter-threats appear on Facebook; everyone seems to have different ideas about what freedom means.

Ennahda and Ghannouchi himself—who has not accepted office, but wields much power behind the scenes—have been damaged by the confusion. Salafists loathe Ghannouchi for refusing to implement Islamic law and for helping to draw up a draft constitution that is, give or take a few vague references to Islam, strikingly secular. (It does not mention the Sharia, for instance, and guarantees equal rights for all Tunisian men and women.) The secularists distrust him for encouraging a more visibly devout Tunisia—including the once-banned wearing of the veil—and suspect him of aiming to Islamicize society by stealth. All the while, international investors, apprehensive about the growing prospect of political instability, are staying away, with the effect of prolonging the current economic slump and prompting Fitch, a credit rating agency, to lower the country’s rating on December 12. The deficit is rising; joblessness is high, with official unemployment figures hovering around 18 percent and unofficial estimates far higher. President Marzouki has warned that the country stands at a “crossroads,” but some young people I spoke to said they were already fed up with politics.

Ennui with democratic politics partially explains the rise of the Salafists. These Saudi-inspired fundamentalists, who claim to be returning to the pure Islam of the Prophet Muhammad, are said to be divided between those who espouse violence openly, like the Ansar al-Sharia, whose Libyan counterpart is thought to have been behind the attack on the US consulate in Benghazi that killed Ambassador Christopher Stevens, and others, such as members of a new (and quite legal) Salafist party, who say they want to take power by constitutional means. In reality, the division is not so clear, and some Salafists have good relations with Ennahda itself. But while their supporters are growing in number, they remain a small minority. In fact, a greater number of Tunisians harbouring grievances against the current government look for guidance to a left-wing, secular organisation: the Tunisian General Labour Union (UGTT), the country’s biggest.

The UGTT had a big part in turning the prosperous coastal towns against Ben Ali after the revolution started in the interior two years ago, and it has become the main opposition force against Jebali’s coalition government. The union orchestrated the agitation in Siliana, calling a halt only after the government acceded to its demands. It won further sympathy after a pro-government group attacked UGTT members outside the union’s Tunis headquarters on December 4.

Since then, the UGTT has been flexing its muscles. Union leaders announced a general strike for December 13, only to put it off after negotiations with the government. Ghannouchi and his allies have condemned the attack, but the union wants them to go a step further and dissolve the group responsible. Plans for a strike may yet be revived, but at least there is a sense that both sides are trying to avoid a confrontation that could topple the government and even push the army (a respected institution—in contrast to the police) to intervene. In 2013, Tunisia is supposed to finalize its new constitution and hold elections. Is the transition under threat?

As an outsider, detached from revolutionary joy and post-revolutionary despair, I came away from Tunisia with a more sanguine view than recent events might seem to warrant. The country has taken important strides toward a more representative and accountable political system. The institutions are working, albeit imperfectly. Freedom of speech is being observed to a degree that is unprecedented in the country’s modern history. To be sure, secularists and Islamists exert themselves to ensure that their view of the world carries the day, but I have spoken to hard-liners in both camps who accept that, for as long as the majority opposes them, compromise is inevitable.

Advertisement

This flexibility distinguishes Tunisia today from, say, Iran after its revolution thirty-three years ago, when armed groups killed and died for the opportunity to take power and crush their foes. The principle of democracy is more advanced in Tunisia than it was in Iran then—and arguably more so than it is in Egypt now. Tunisia’s current leaders have neither tried to ram through a constitution nor sought legal immunity for the actions of the executive.

Even now, after the bruising experience of holding power, the principles championed by Ennahda remain the likeliest blueprint for the country’s future. And this brings us back to the movement’s founder, Ghannouchi himself. Depending on your perspective, his moderate, incremental Islamism can seem virtuous or sinister; equally, it can be read as a pragmatic reaction to events, an acknowledgement of the impossibility of attaining every goal.

I had found myself sitting near him on my flight from London to Tunis (he had been picking up a prize from the British think tank Chatham House) and, speaking the English he had learned over long years in exile in Britain, he told me that he feared the initial spirit of solidarity that the revolution had engendered seemed to be seeping away. He was dispirited by the mauling the government had received at the hands a newly empowered (and mainly secular) media, and the unrealistic expectations of the people. But his vision, of a variegated world with room for competing visions, seemed intact. “There is more than one interpretation in Islam,” he said—a view that the Salafists hate.

He had, I discovered, been urging pragmatism on the Tunis Air flight attendants. Behind a curtain on the drinks trolley, he told me, were hidden different sorts of alcoholic beverage. You only needed to ask, and you would be served. “The flight attendants are unhappy,” Ghannouchi went on.

“They tell me they are good Muslims—they pray and fast and so on—and yet here they are: obliged to serve alcohol. And I say to them that this is the way things are. We live in a society where a lot of people drink alcohol. And so, we must accept the logic of this reality.”