Huang Qi is best known in China as the creator of the country’s first human rights website, Liusi Tianwang, or “June 4 Heavenly Web.” A collection of reports and photos, as well as the occasional first-person account of abuse, the site is updated several times a day. It documents some of the hundreds of protests continually taking place in China, many related to government land seizures.

The forty-nine-year-old Huang launched his site in 1999, at first concentrating on human trafficking and abuses of workers. Initially lauded by government media, he was detained in 2000 when he broadened his scope to include the plight of people still suffering from their participation in the June 4, 1989, Tiananmen protests. He also documented abuse by the authorities of members of the banned spiritual movement Falun Gong. In 2000 his site was blocked by authorities in China so he moved it to US-based servers. A few months later, he was detained and imprisoned for five years on charges of “subversion.”

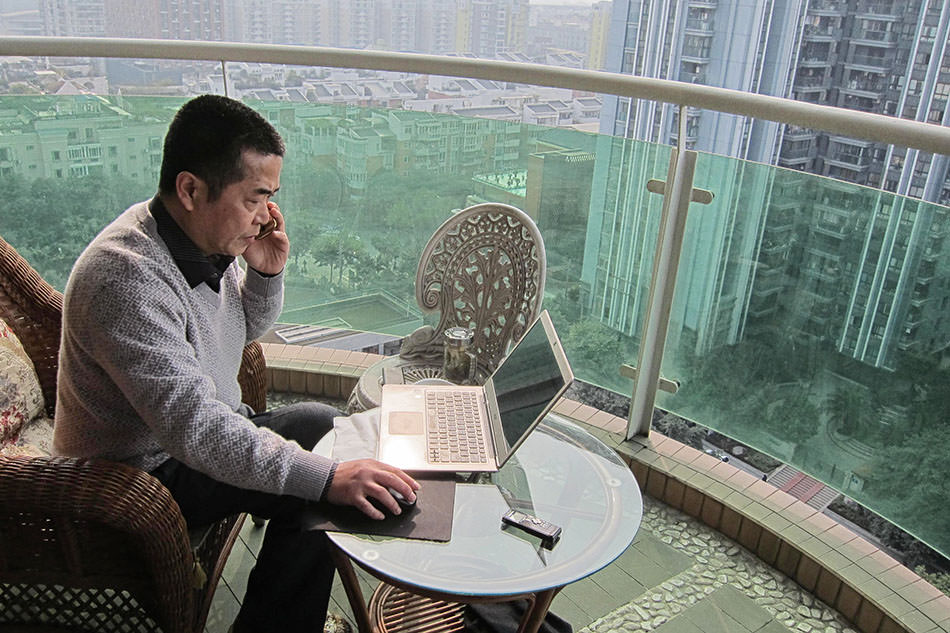

Since being released from his second prison stint a year and a half ago, Huang has lived in a series of apartments in the southwestern city of Chengdu. All are lent by supporters, and are near hospitals so he can have dialysis for his ruined kidneys. Most recently, he has been living on the sixteenth floor of a high-rise, and when I went to see him in January, he was sitting out on the balcony in the early spring air, fielding a string of calls from China’s farmers and lower middle class—the people driving the country’s slow-motion revolution to make the government more accountable. Fueled by cigarettes and green tea, he listens to their stories, cuts them off when he has to, gives curt advice, and types out a few lines for his website on the latest protests and beatings.

Ian Johnson: Your new apartment complex has all sorts of security outside. Are they just private or do they work for the government? Their uniforms make them look almost like the police.

Huang Qi: Some of the police outside are plainclothes. But for me they have a protective use. People like us who are working in human rights are taking on the personal interests of corrupt officials and others. We are very vulnerable if they come after us. So this sort of police control is actually good for us!

I’m lucky to live here. People have donated this to me. They know I’m quite ill and they want something that can help my health. Basically everything I have here people donated. I don’t really own anything. The furniture, the computer, even the fruit here is donated.

(His phone rings, and he speaks into the receiver.)

Where are you from? Sichuan Suining? A lot of people are out there? How many? Ok, I know about it. Ok, thanks. A lot were detained, right? Ok, don’t worry, we have it.

(Referring to the call.)

It’s like this: Sichuan is holding its provincial level congress right now in Chengdu so people are coming here with their complaints and grievances hoping for a hearing. Today the authorities have detained a lot of people. That person was from Suining. He was detained and beaten. This morning there was a similar case.

(Another call comes in; he answers.)

You’re from Hubei. How do you spell your name? Today how many were protesting? Two hundred? How many were released? So listen, can you take a picture of your torn clothes and bruises and send it to my cellphone? Ok, rest assured I’ll take care of it. Ok, don’t worry. Ok, I’ve got it. Keep your phone turned on, ok?

You just told that woman that you’d “take care of it.” How can you?

The first thing is we have to get the information out. You have to understand that the public security and government agencies are monitoring our site. They read it. News services too. After we publish, it’ll get the attention of the relevant authorities. So we have to send it out and then people can learn about it. That’s how we do it.

Wait a minute, ok? I’m sorry but two hundred people detained is something else. I have to get it out now. (Huang turns to his computer and types up the article. He reminds me of the blogger Zhu Ruifeng, who has exposed the private lives of allegedly corrupt officials. The difference is that Zhu receives official leaks—for example, videos of naked officials. Huang’s sources are ordinary people who call him, making his site a bottom-up view of unrest rather than a reflection of internal power struggles.)

(Huang’s phone rings and he answers again.)

You need to do this properly. Are you at the Public Security now? You’re at the Beijing Municipal Public Security Bureau, right? They didn’t tell you why they called you in, right? It was just to harass you. Ask them. Ask them. Ask why you’re in there. You need to be a bit more courageous. Use your cellphone and take a photo!

Advertisement

(Huang hands his cellphone to a volunteer assistant and asks her to handle calls for a while. Then he turns to me.)

After 2006 we handled mainly farmers’ cases and land disputes. While I was in prison, the government discovered that land was profitable and began expropriating it and selling it to developers. Then of course the Wenchuan earthquake happened in 2008. We were one of the first to report it. I think we were a few minutes faster than any international media. I went to the area to volunteer. We quickly found that there had been a lot of shoddy construction. The schools were the worst; in some places they were the only structures that collapsed. We published pictures and many people came here to Chengdu to my offices [to bring photos and documentation of the corruption that had caused the poor construction]. We published this earthquake building information on our website. So on June 10, twenty-eight days after the earthquake, I was detained and later sentenced for revealing state secrets [a standard charge used against political activists for publicizing embarrassing information].

You say you get 150 calls or messages a day. Do you think the situation is particularly bad in China right now?

In mainland China, especially since the so-called reform and opening up period began [in 1978], Chinese society has shown all the ill deeds of humanity. No matter whether you’re talking about monopoly of power, or the problems Latin American countries experienced during their modernization in the 1960s, or environmental problems—all the problems present elsewhere in the world are found in mainland China. So right now, the situation for people at every social level is horrible.

What motivates people to donate to your cause?

Until 1998 I was a businessman and I earned well and had savings. Back then most petitioners were destitute. We used to give them money for food or travel. So by 2000 I had used up my money. But in the early 2000s, you started having people who own property that was being expropriated by the government. The big change now is that middle-class people have entered human rights work. It’s no longer just a few intellectuals or dispossessed poor people. This has pushed our work forward incredibly. This is also why there’s such an explosion of petitioners. In the past it was hard for people to afford the travel and accommodations to go petition the provincial or national government. Now, people have money to do this. And some help us out.

We are trying to record actual violations of human rights in China. Most of these violations have never been reported before. They are from people calling us up and asking us what to do. We offer some legal advice. We have people who have served time in prison or have legal training so we can help in some way. But the main thing we can do is provide a record. Authorities can then see what is happening.

What would you like to see happen?

I think it has to start with protecting ordinary people’s rights to petition and oppose corruption without being arrested. If that can happen then it’s really a significant improvement. You can oppose the Communist Party, but someone will rule the country—and even if they call themselves the “Democracy Party,” without a change in structures it’ll be the same. So it’s only if people take control of their lives and monitor officials that there will be an improvement.

If all we do is call out “down with the Communist Party” or whatever slogan you want, it isn’t as good as actually doing something. In mainland China, those shouting slogans are dozens of times more numerous than those actually doing things. This is a reason why in China we’ve been talking about human rights for so many years but haven’t achieved that much.

So what’s really changing? Why are you optimistic?

In my 2000 indictment, they said it was a crime for me to have started “China’s first human rights website.” But now human rights is at least officially enshrined in the constitution. So you can see that what we want isn’t illegal anymore—the government talks all the time about human rights so the discourse has changed. It is significant because now they can’t arrest you for doing what we did in the late 1990s. There are still a lot of these cases but since Xi Jinping has come to power there’s been a big change. It’s heading in a more positive direction.

Advertisement

You think so? When did it start?

Probably just before Xi took over [in November] the change was noticeable. In the past, at least 99 percent of people who were petitioning the government were detained and sent to some sort of facility. But now those who are detained are maybe just 10 percent. Since the Eighteenth Party Congress, China has emphasized protecting the rights of ordinary people and fighting corruption. So if you look at it from an overall perspective the situation is improving.

And the protests have caused this change?

They’ve changed how the government sees things. It’s like with Washington and the American revolutionaries. Were they able to sit down and talk to the British as equals? No, not until they’d defeated them militarily and then the British realized they had to talk to them. It’s like that with us now. It’s only after pressure from the people that the government will change its opinions. I don’t mean we want to sit down and negotiate with Xi Jinping! But I mean that the government will treat the people as equals. It’s because they are standing up and people are reporting it. There is a change afoot. In 2000 this was illegal and in 2008 it was illegal but now I feel it’s legal. Things are changing.

Your website is still blocked in China.

Yes, but the officials who need to know can access it. They are aware of it. It’s not unread. We know that from the feedback we get.

You get so many calls. When do you sleep?

Most days I sleep at 3 or 4 AM. You see, people might be detained in the middle of the night so we have to be there for them. But ordinary people know my health situation so they try not to call too late. Some send text messages or emails.

How was your health damaged?

The first time I was in prison I was beaten. You can find pictures of me on the Internet with a bloody face. I also spent a year in solitary confinement sleeping on a concrete floor. I don’t know about the kidneys. They went two months after I was released in 2011.

You don’t turn off your phone?

You can’t turn it off. What if they need you urgently?

Part of a continuing series of interviews by Ian Johnson with Chinese writers and thinkers. Among previous subjects are Ran Yunfei, Bao Tong, Yu Jie and Chen Guangcheng.