Observers should be excused for being surprised by the White House’s seemingly unplanned statements on human rights issues over the past week. At a news conference on Tuesday, President Obama responded to a question about Guantánamo by calling it “not sustainable” and “contrary to who we are.” And just a few days earlier, on April 26, Vice President Joe Biden said he thought that the Senate Select Intelligence Committee’s as-yet-unreleased six-thousand-page report on the CIA’s “enhanced interrogation” program should be made public. Coming after four years of near silence on the post-9/11 legacies of torture and indefinite detention, these statements have many asking, What changed? And more importantly: Will the administration follow its rhetoric with concrete action?

Consider the president’s words about Guantánamo, which sound as if they came from a spokesperson for Human Rights Watch:

It’s not sustainable. I mean, the notion that we’re going to continue to keep over a hundred individuals in a no man’s land in perpetuity, even at a time when we’ve wound down the war in Iraq, we’re winding down the war in Afghanistan, we’re having success defeating [the] al-Qaida core, we’ve kept the pressure up on all these transnational terrorist networks, when we’ve transferred detention authority in Afghanistan—the idea that we would still maintain forever a group of individuals who have not been tried—that is contrary to who we are, it is contrary to our interests, and it needs to stop.

The most plausible explanation for this sudden outspokenness seems to be the decision by at least one hundred detainees at the prison to join a hunger strike. The strike, which began in February but has drawn increased public attention in recent weeks, has led the military to dispatch forty extra medics to the island to address the situation, in which twenty-three men are now being force-fed through their noses. The American Medical Association has warned the president that force-feeding violates core principles of medical ethics. And on Wednesday, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, the UN Working Group on Arbitrary Detention, and the UN Special Rapporteurs on Torture, Human Rights and Counter-Terrorism, and Health reiterated their call for an end to indefinite detention at Guantánamo.

Regarding the CIA interrogation program, Biden’s call for public disclosure, made during an appearance at a forum in Arizona with Senator John McCain, may have been prompted by a report issued by a bipartisan task force organized by the nonprofit Constitution Project. Co-chaired by Asa Hutchinson, a former Bush administration official, and James Jones, a former Democratic representative and ambassador to Mexico, the task force’s 566-page report concluded that “it is undisputable that the United States engaged in the practice of torture,” and that “the nation’s most senior officials…bear ultimate responsibility for allowing and contributing to the spread of illegal and improper interrogation techniques.” Demonstrating that members of both parties can agree on the need to hold the government accountable for torture, the Constitution Project’s report may have encouraged Biden to call for disclosing the far more detailed Senate report.

The Senate intelligence committee had subpoena power and access to the CIA’s secret records, and according to some of those who have seen the report, it establishes that the government’s practices were even worse than what is now publicly known. Such an official government report could, much like the Church Committee reports on COINTELPRO and other illegal spying in the 1970s, move us toward the national reckoning with torture that has thus far eluded us, and provide impetus for future safeguards.

Obama’s and Biden’s statements have been regarded with skepticism by some who recall the administration’s promises in 2009 to close Guantánamo and to be as transparent as possible. In fact, the administration has done little to make good on these promises. On Guantánamo, habeas corpus litigation, once a critically important ray of hope, has not resulted in a single detainee being released against the executive branch’s will. Congress has barred transfers of any detainees to the United States, and erected substantial barriers to transfers even to other countries.

On the matter of torture, meanwhile, accountability has been frustrated at every turn. Attorney General Eric Holder has declined to pursue criminal prosecutions; the courts have barred all civil lawsuits on grounds of national security and secrecy; a Justice Department official has vetoed the Office of Professional Responsibility’s referral of the torture memo authors for bar discipline; and President Obama himself has resisted all calls for a bipartisan commission of inquiry.

And yet we’ve seen Biden’s off-the-cuff remarks push the president to do the right thing in the past—consider what happened with gay marriage. It also seems unlikely that President Obama would have spoken so passionately on Guantánamo without a sincere desire to resolve the human rights issues it raises. So what can the administration do?

Advertisement

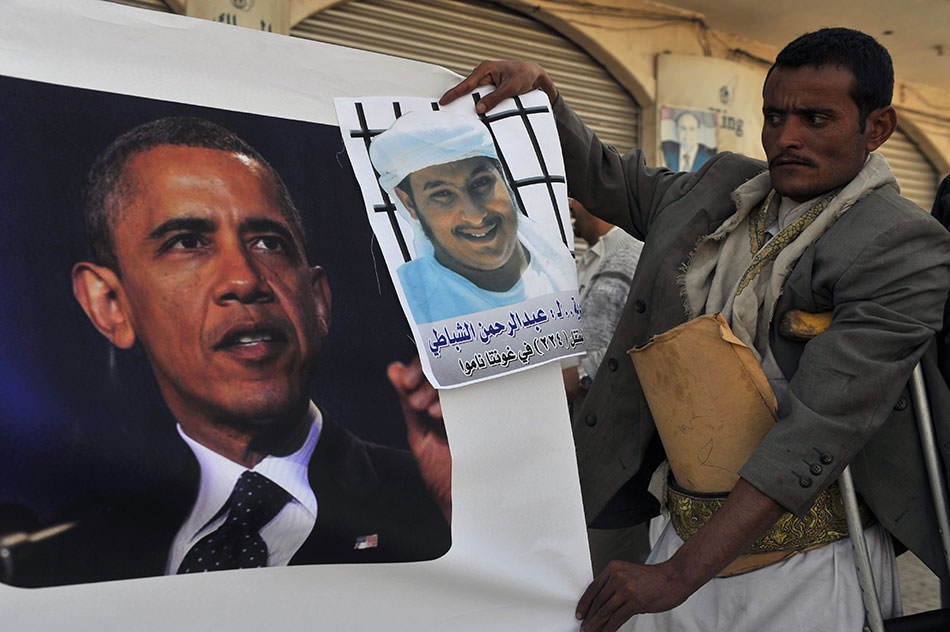

Until now, President Obama has put the blame for failing to deal with Guantánamo on Congress. Without question, Congress has made his job more difficult by obstructing detainee transfers with onerous “certification” requirements—essentially asking the administration to guarantee that no harm will ever come from a detainee’s release. But there are steps the president could nonetheless take. For example, the current law permits the executive branch to waive some of the requirements when the transfer “is in the national security interests of the United States.” Moreover, eighty-six detainees have been “cleared for release” but remain in detention. Fifty-six of them are Yemeni citizens, and it was President Obama, not Congress, who placed their release on hold.

The administration, which this week reaffirmed the moratorium on transfers to Yemen, says that it is concerned about the Yemeni government’s ability to prevent individuals from joining militant groups that may want to attack the United States. But if these men have been cleared for release, then the military has determined that their detention is no longer warranted by security concerns. Is it moral or legal to hold these men simply because their home country is unstable? Shouldn’t the onus be on us to uphold their right to freedom, and then provide whatever assistance we deem necessary to reduce any risk to an acceptable level?

Reasonable people can differ about how long persons found to be fighters for al-Qaeda and the Taliban can be detained, especially as the war in Afghanistan winds down. But how can anyone justify the continued incarceration of a human being who the government has determined no longer warrants detention? That is the very definition of arbitrary detention—to detain without just cause.

Some of the other cleared detainees cannot be returned to their countries of origin because of risks that they would be tortured there, but if that is the case, we should either find a country to accept them, or release them here in the United States. Continued detention of an individual cannot be justified simply because it is politically challenging to find a place where that person can live freely.

At his press conference President Obama said, “I think all of us should reflect on why exactly are we doing this. Why are we doing this?” The detainees at Guantánamo have been asking that question for a very long time. It’s time President Obama answered the question, released those who have been cleared, and announced what his plans are for those who the military deems cannot be released. He needs help from Congress, to be sure, but there is plenty he can and should do in the meantime to restore liberty to those whose detention he himself concedes has no valid national security basis.

President Obama should also side with his vice president and call for the release of the Senate report on CIA interrogations. The administration’s strategy to date on torture has been suppression and censorship. It has classified the detainees’ own accounts of their mistreatment, and barred them or their lawyers from even mentioning these accounts in public. But as the president said of Guantánamo itself, that strategy is “not sustainable.” Just as we cannot detain indefinitely, we cannot suppress the truth forever. We can only hope that the remarks of the past week reflect an administration, with an eye to its legacy, ready to confront head-on the moral challenges that it ran away from in its first term.