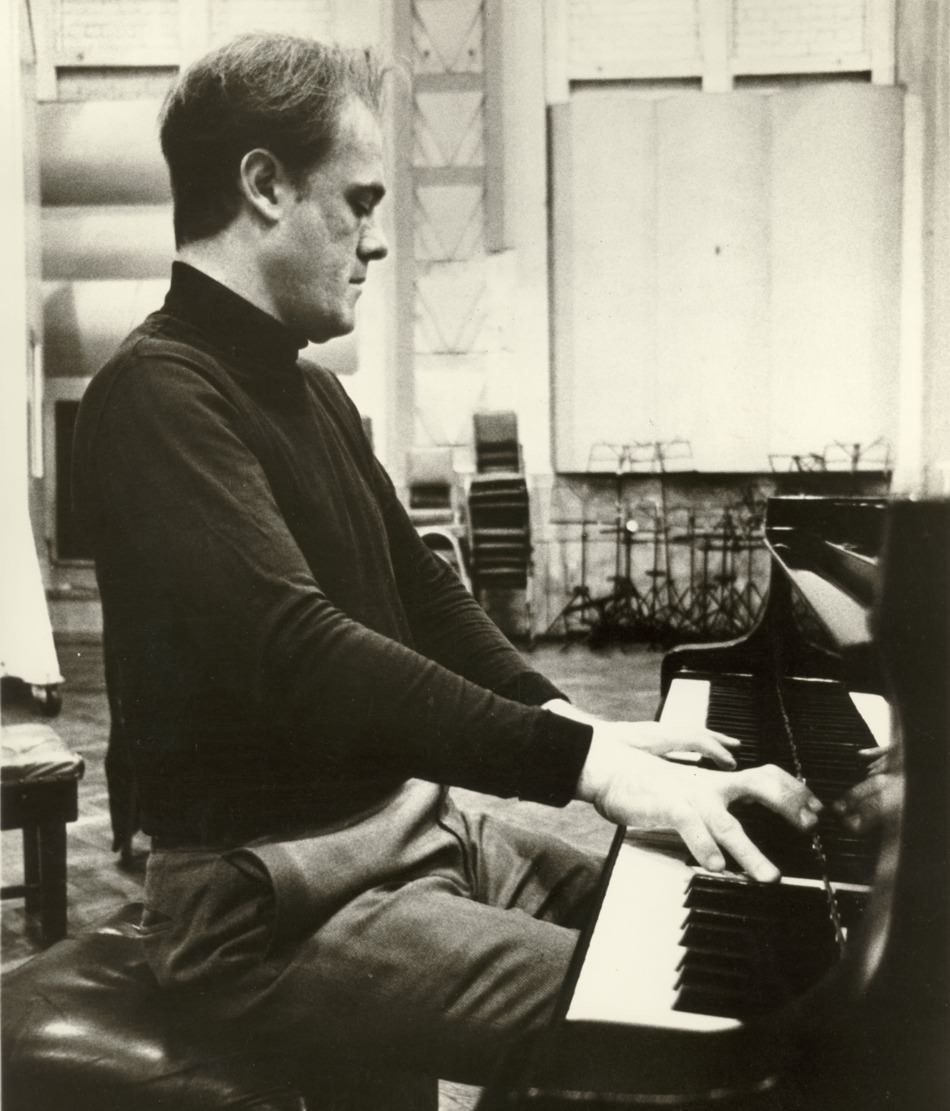

Frédéric Chopin was “the greatest master of counterpoint since Mozart”—so claimed the late pianist and author Charles Rosen in a 1987 review in these pages. At the time I read this, it came as a double surprise to me. I had never thought of Chopin’s music as having a lot of contrapuntal interest, or even Mozart’s for that matter. (Wasn’t it the alleged lack of mature counterpoint in Mozart that made Glenn Gould so disdainful of his piano sonatas?) I had always imagined Chopin’s music to stress sonority over structure, to be more emotional—even sentimental—than intellectual: a sort of higher mood music. But I knew that Charles Rosen’s intellectual grasp of music was peerless, not only on the page but also at the keyboard. I particularly prized an old recording I had of Rosen playing Beethoven’s Hammerklavier sonata, for the noble clarity he brought to the fugal passages.

So when, a few years later (in 1990), Rosen came out with a recording of two dozen of Chopin’s Mazurkas, I eagerly purchased the CD (at the now-vanished Tower Records on lower Broadway). It was in the folk-infused Mazurkas, Rosen had observed, that Chopin’s skill at classical counterpoint, his ability to create a play of inner voices, “is paradoxically most marked.” And what a revelation Rosen’s performance proved to be. Finally, the almost Bach-like traces of polyphony in Chopin’s music were made apparent even to my ear, in a way that the other recordings I had of the Mazurkas—by Arturo Michelangeli and Ivo Pogorelich—never managed to do. In The New York Times, music critic Harold Schonberg hailed Rosen for having given us “the finest modern recording of these elusive pieces.”

Today, sadly, Rosen’s recording of the Mazurkas is out of print and almost completely unavailable, as is so much of the rest of his catalogue (with some happy exceptions, like Rosen’s definitive performance of the complete piano works of his friend Elliott Carter). Here, however, is Rosen’s performance of the last-published of the Mazurkas, opus 63 no. 3, in C# minor, which Chopin ends with a canon—a simple form of counterpoint—created from the lovely opening dance theme. Listen to it and you may come to agree with Rosen’s judgment that “Of all the short works of Chopin, it is the Mazurkas that capture the full range of his genius.”

Charles Rosen’s review “The Chopin Touch” appeared in The New York Review’s May 28, 1987 issue. His second piece on Chopin, “Happy Birthday, Frédéric Chopin!” appeared in the June 24, 2010 issue. He also recorded a podcast on the composer, in which he played and discussed several of Chopin’s compositions.

To read more by Charles Rosen, visit our archives.