While movie directors are regularly given retrospectives, few have been the subject of museum exhibitions. Hitchcock had one at the Montreal Museum of Fine Art in 2000; Godard was accorded an exposition at the Centre Pompidou six years later; and, moving down the ladder of greatness a few rungs, the Museum of Modern Art’s 2010 Tim Burton show proved to be one of the most popular in its history. But David Cronenberg had been there first, getting his first show at the Royal Ontario Museum, organized by Tokyo’s Seibu department store, in 1993. This fall, Cronenberg, who turned seventy this year, is the subject of three new exhibitions in his native Toronto—the main one, “David Cronenberg: Evolution,” devoted to his film work, another curated by him, the third consisting of artworks commissioned in his honor.

To the general movie-going public, Cronenberg is likely best known for The Fly (1986), a luridly operatic remake of a 1950s drive-in horror film, in which a scientist played by Jeff Goldblum inadvertently transforms himself into an insect—Gregor Samsa in the age of AIDS. But many career-long Cronenberg concerns (body horror, cyberpunk, regendered sex acts) and tropes (viral epidemics, organic glop in institutional settings) have parallels in the work of gallery artists, and he is one of the few filmmakers whom artists regard as a colleague and perhaps a model. In the current Cronenberg-inspired art exhibition, Candice Breitz’s two-channel video “treatment” turns three scenes from his early, most personal film, The Brood, into a ritualized drama involving her own family.

Cronenberg is a filmmaker of ideas, one being the notion that human beings have merged with technology. His protagonists are often cyborgs as, in some sense, he is as well—not a commercial director with artistic aspirations so much as an avant-garde filmmaker who has contrived a commercial career, in part by remaining in Canada. The dark comedy Videodrome (1984), a suave, sleazy work of social science fiction with a Salvador Dalí taste for extravagant visual shock, has particular art-world credibility. A TV broadcaster is taken over and mutated by a malign television signal, illustrating Marshall McLuhan’s conceit that humans are scarcely more than an ascendant technology’s reproductive organs.

Dense and dark, “David Cronenberg: Evolution,” is on view at the new TIFF Lightbox in downtown Toronto through mid-January. It is primarily a fan’s delight, rich with clips, lobby cards, sketches, and letters (“Saw The Fly—loved it,” Martin Scorsese writes). Pull-out drawers yield facsimiles of annotated scripts and unrealized treatments. One, Roger Pagan, Gynecologist, suggests that years before he made his supremely unsettling Dead Ringers (1988), the tale of twin gynecologists whose sexual exploitation of their patients veers into madness, the artist was pondering its subject. A small exhibition could be contrived from Cronenberg’s research material—the motorcycle motor that served as the model for the pod-like teleportion device in The Fly, the medieval medical implements he studied for Dead Ringers, or the 1920s photograph of a professional exterminator in bowler hat and suit, crouched by ornate radiator, that was used for Naked Lunch.

Though not without a few silly digressions, such as the room that allows visitors to have their picture taken with one of Naked Lunch’s mugwumps, “Evolution” gives a convincing tri-part form to Cronenberg’s career. The first third is devoted to the outré genre films of the 1970s (Shivers, Rabid, The Brood), which followed from his initial forays as a student at the University of Toronto and are notable for their disturbing premises and disgusting special effects. This segues into the character-driven features of the 1980s and 1990s, many of them “impossible” literary adaptations—William Burroughs (Naked Lunch, 1991); J.G. Ballard (Crash, 1996). Most of the films of this period involve protagonists who, whether scientists, artists, or thrill-seekers, perform their experiments mainly on themselves.

The final third considers Cronenberg’s recent concern with family dramas and the social world, refining his overarching interest in subjective psychic states made material. A short film created for the exhibition and shown, surrounded by artifacts from eXistenZ (1999) and Naked Lunch, in a space identified as the Canadian Academy of Erotic Inquiry, is a Warholian single-take interview of a partially nude woman doggedly explaining to an off-screen doctor that she is undergoing a mastectomy in order to destroy the insects living in her left breast.

The middle section of “Evolution” is the juiciest largely because it includes the props fashioned for his movies: the “body slit” that turns James Woods into a living VCR in Videodrome, various insect-human ears and teeth culled from The Fly, the “sex blobs” and the bug-like “Clark-Nova Typewriter” that appear in Naked Lunch, eroticized body braces used in Crash, the sinister “Instruments for Operating on Mutant Women” invented by the insane gynecologist in Dead Ringers. (These fetishes are amplified by the art objects Cronenberg himself selected for the satellite exhibit “David Cronenberg: Through the Eye.” Louise Bourgeois’s headless midair suspension Arch of Hysteria is a sculpture that in its agonized-ecstatic representation of a disembodied body could have presided over any number of Cronenberg productions.)

Advertisement

Retrieved from the world of images, Cronenberg’s props are eerily diminished. They appear as shrunken heads, supporting actors in a creepy state of suspended animation. It’s striking that eXistenZ, a send-up of computer games that parodied The Matrix avant la lettre, and one of the great underappreciated movies of the late 1990s, yields the richest trove of relics—cutely deformed amphibious creatures, latex “game pods” and “umby cords” that allow players to plug into virtual worlds, boxes for imaginary games with titles like Viral Ecstasy and Hit By a Car, and numerous iterations of the so-called “gristle gun” which, as an organic thing that eludes metal detection, allows a disgruntled fan to assassinate Jennifer Jason Leigh’s game designer character.

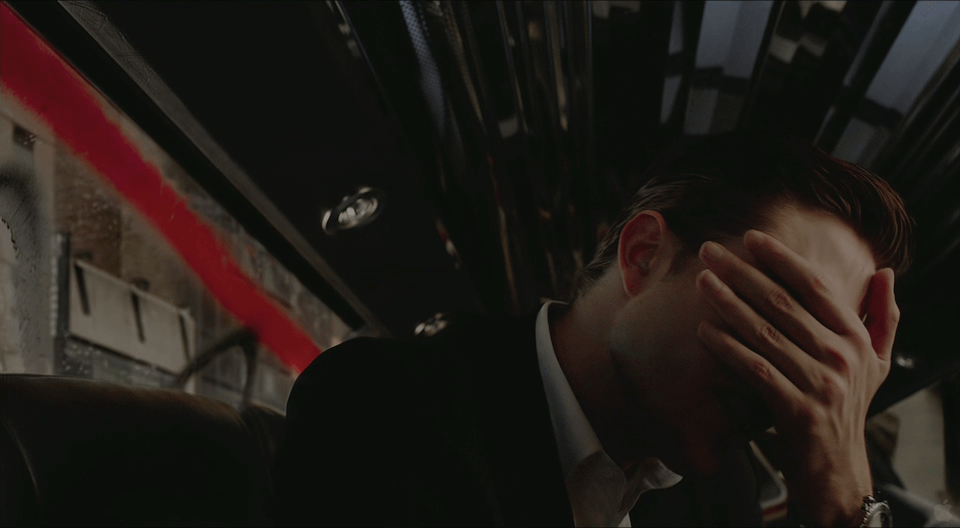

Cronenberg is here revealed as a literalist whose initial response to the rise of computer-generated imagery was to fabricate a virtual world that was wholly real. But, after eXistenZ, the artifacts disappear. Cronenberg’s twenty-first century films accept themselves as traces; they are now viscerally cerebral. There are no props from Spider (2002), a movie adapted from Patrick McGrath’s novel that takes place mainly inside the mind of its deranged protagonist (released from a hospital for the criminally insane, he revisits and “relives” his childhood); the deceptively “normal” thriller A History of Violence (2006), in which the protagonist’s submerged personality shatters the bland façade he’s hidden behind, contributes only a coffee cup to the exhibition. Eastern Promises (2007), a relatively lavish evocation of Russian gangsters in London, has a few set designs and maquettes of the faux-opulent restaurant that functions as the epicenter of conspiracy. Period costumes are the lone physical manifestation from A Dangerous Method (2011), a movie devoted to Jung’s lover and Freud’s disciple, Sabina Speilrein. There are only a few images from the artist’s most recent film, the ultra-formalist Cosmopolis (2012), which, even more than most late-period Cronenberg, has been misunderstood and underappreciated.

With its synthesized backgrounds, Cosmopolis was Cronenberg’s first movie to make extensive use of digital photography and CGI. It not only illustrates DeLillo’s metaphor for global capital but is a sustained riff on the idea of a virtual world. Indeed, Cosmopolis marks Cronenberg’s embrace of the virtual; fittingly, there’s no place for it in “Cronenberg: Evolution.” The movie’s central prop—the enormous limousine that creeps through midtown Manhattan—was destroyed in the course of making the movie. Its only existence is as a memory on screen.

“David Cronenberg: Evolution” is at the TIFF Lightbox HSBC Gallery in Toronto through January 19, 2014; “David Cronenberg: Transformation” and “David Cronenberg: Through the Eye” are at the Museum of Contemporary Canadian Art in Toronto, through December 29, 2013.