As the winter season of New York high culture kicks into full swing, one thing seems quite apparent: there is little appetite for the new in the performing arts here, because innovation carries so much financial risk. At the New York Philharmonic, the coming weeks foretell Mozart, Dvořák, Beethoven, and Handel; at the Metropolitan Opera, apart from the sparsely attended and now closed Two Boys, the current repertoire features crowd-pleasing standards like Rigoletto, Tosca, Der Rosenkavalier, and The Magic Flute. More daring options can be found among nimble smaller outfits like the Gotham Chamber Opera, but they have to fight at the margins of the city’s arts landscape. In view of such a situation, the demise earlier this fall of the adventurous but profligate New York City Opera—and the particular qualities of its last staging—provide a kind of case study in the predicament of major cultural institutions today.

The New York City Opera needed a sugar daddy just as much as did Anna Nicole Smith, the feckless subject of its electrifying swan song, Mark-Anthony Turnage’s Anna Nicole. In both instances, an ambition-success-profligacy-bankruptcy-death scenario was played out very publicly, although it would be a mistake to equate the august NYCO with a drug-addled former stripper. Yet the lack of a patron as indulgent and deep-pocketed as J. Howard Marshall II, the Texas oil billionaire who married Smith when she was twenty-six and he eighty-nine, spelled doom for the long-admired company, even as this production showed off so many of its artistic strengths.

As is now well known, soon after this fall’s seven-performance Brooklyn Academy of Music run of Anna Nicole (which had its premiere at London’s Royal Opera House in 2011), the “People’s Opera” filed for bankruptcy protection. A last-ditch fundraising campaign failed to meet the $20-million quota deemed necessary to keep the company afloat, and no deus ex machina materialized to save the day.

Anna Nicole Smith is but the latest heroine in a long operatic lineage of courtesans, demimondaines, trollops, tramps, and whores, an erotic sisterhood that includes Verdi’s Violetta Valéry, Puccini’s Manon Lescaut, Weill’s Jenny, and Berg’s Lulu. Anna Nicole also reminded me of Paul Hindemith’s 1929 satiric opera Neues vom Tage (News of the Day) and Kurt Weill’s 1930 Aufstieg und Fall der Stadt Mahagonny (Rise and Fall of the City of Mahagonny), both of which anticipated today’s voracious mass-media cycle, rampant commercialism, and institutionalized greed, all of which figured prominently in the Smith story.

Those three contemporary phenomena have coalesced in the prurient degradation fostered by “reality” television, of which Anna Nicole’s rise and fall was an early manifestation. Her tangent traced a poor girl from Mexia, Texas, who married, had a son, and separated all before she turned twenty; took low-wage jobs at Wal-Mart and Red Lobster before turning to more lucrative work in strip clubs; and soon divined that the path to stardom in her chosen profession was huge artificial breasts.

Alas, although these prostheses brought Smith the attention and money she craved, the back strain they caused led her to take painkillers, to which she became addicted. (Her drug abuse before that mammary transformation is not emphasized in Anna Nicole.) How fitting and dispiriting that an opera so determined to adapt to the times was produced by a company that ultimately failed to do so.

The libretto by Richard Thomas is a vibrant mash-up of contradictory attributes, at once slangy and poetic, filthy and elevated, hilarious and touching. The most trenchant lines were delivered by the chorus, a hortatory crew who in the NYCO presentation were as admonishing as any band of onstage commentators since the ancient Greeks, though rather more profane:

Once upon a time

Not so many years ago

There was a lady

Who wanted to be Marilyn Monroe?

Marilyn Monroe

Some saw her as an icon

Others as a ho…Stripper, playmate

Wife of a billionaire

She tried to make her mark

She tried to get her share

Tabloid queen

Borderline obscene

Known across the globe

In all its cities

For her sensual peccadilloes

And her silicone titties…… This is one bleak nihilistic tale

An absurdist tale of woe

About a beauty wannabe

Who was gone from the get-go.

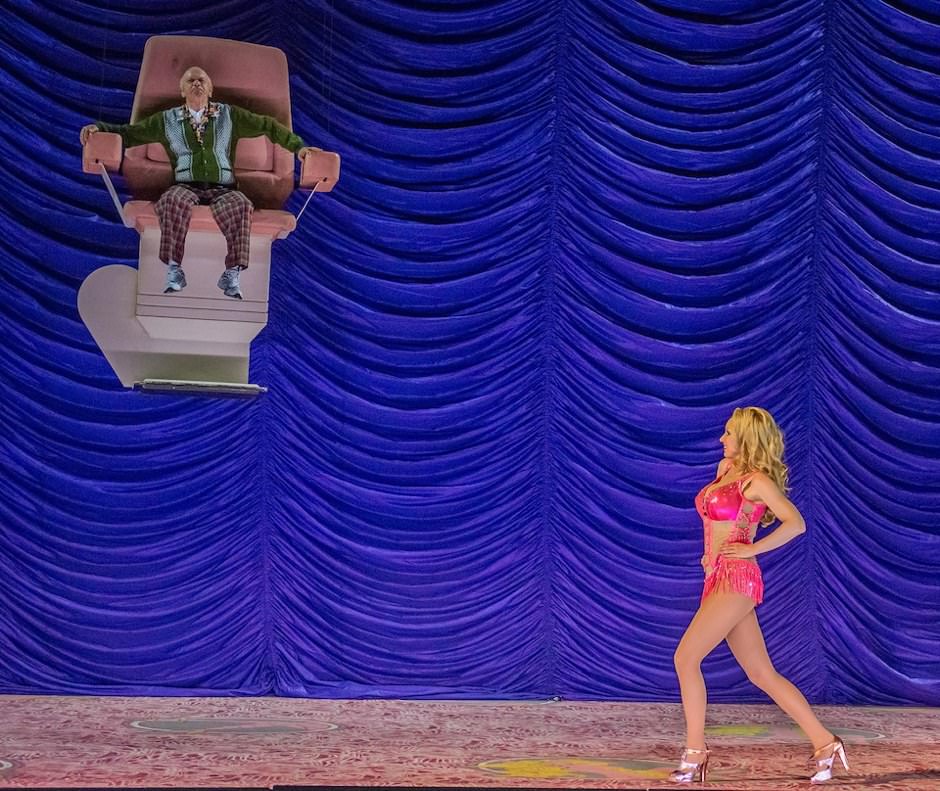

In the title role, the stunning Sarah Joy Miller displayed a mixture of dramatic credibility, musical confidence (if not flawless voice), and flat-out sexiness that I have not witnessed since the German soprano Anja Silja’s mesmerizing Salome in the late 1960s. Miller was supported by a superb cast that featured Robert Brubaker as Marshall, her codgerly but still horny meal ticket; Rod Gilfry as her opportunistic lover and shyster lawyer Howard Stern; and Nicholas Barasch as Anna Nicole’s adored but understandably screwed-up son, Daniel, a non-singing role that culminates with a plaintive litany of the multiple drugs that ultimately kill him. Conductor Steven Sloan delivered a brisk, authoritative account of the staccato, propulsive score.

Advertisement

What astonishes, in retrospect, is that such a fresh and convincing production seems to have reached the stage in New York only through an opera company that had long ago stopped paying heed to financial solvency. The New York City Opera was founded in 1943 by the populist but opera-loving Mayor Fiorello H. LaGuardia. His goal was to bring high musical culture to average citizens—the city’s garment workers, longshoremen, domestics, shopgirls, and cops—modern-day successors of Walt Whitman’s culture-hungry “best average of American-born mechanics.”

Within two decades the scrappy company rose to international prominence through bold modern programming (it mounted the American premieres of Bartók’s Bluebeard’s Castle in 1952, Poulenc’s Dialogues of the Carmelites in 1957, and Schoenberg’s Moses und Aron in 1966); sensitivity to social issues (the baritone Todd Duncan became the first black singer to appear with a major American opera company in an NYCO Pagliacci in 1945); and home-grown world-class stars (including Beverly Sills, Tatiana Troyanos, Norman Treigle, and Donald Gramm). During the 1960s and 1970s, it often outshone its older, richer, and more tradition-bound Lincoln Center neighbor, the Metropolitan Opera.

The demise of NYCO was in large measure a result of greatly reduced government support for the arts and the tendency for major private donations to gravitate toward more socially prestigious (and conservative) institutions, like the Met Opera and the New York Philharmonic. Yet there can be little doubt that the company’s future was also undermined by some disastrous financial decisions that were not directly related to its programming, as detailed in a New York Times report by James B. Stewart.

The management’s two raids on the company’s endowment to cover operating expenses should never have been condoned by the trust’s overseers. That fatal mistake was compounded by the subsequent decision to abandon its longtime base at Lincoln Center’s New York State Theater (where it moved from the midtown City Center of Music and Drama in 1965) and decamp to less costly venues around the city, such as BAM, which were also less enticing to its older core clientele.

This debacle is evidence of the waning constituency for classical music in this country—and particularly for serious contemporary works. This is reflected not only by the growing conservatism of established musical institutions, but also by the aged demographic of their audiences and a shift away from the cultural aspirations of European immigrant groups who once looked on Carnegie Hall as America’s Parnassus. Thus it seemed particularly ironic that the final NYCO staging was an effort lost on a society where the “reality” TV pioneered by Anna Nicole Smith triumphs, while an opera about her—as populist as can be imagined in today’s society—was far too highbrow to save an opera company founded to bring high culture to the laboring masses.

There seems to be a further paradox to this sad denouement: while the New York City Opera’s plebian orientation discouraged more traditional bases of support, the middle class constituency it courted was not much of a source of funding beyond their contributions as taxpayers. Perhaps opera was always too rarefied to be marketed as a populist pleasure, but in some sense NYCO’s real downfall was not its civic aspirations, but its failure to sell them to today’s increasingly plutocratic arts establishment.