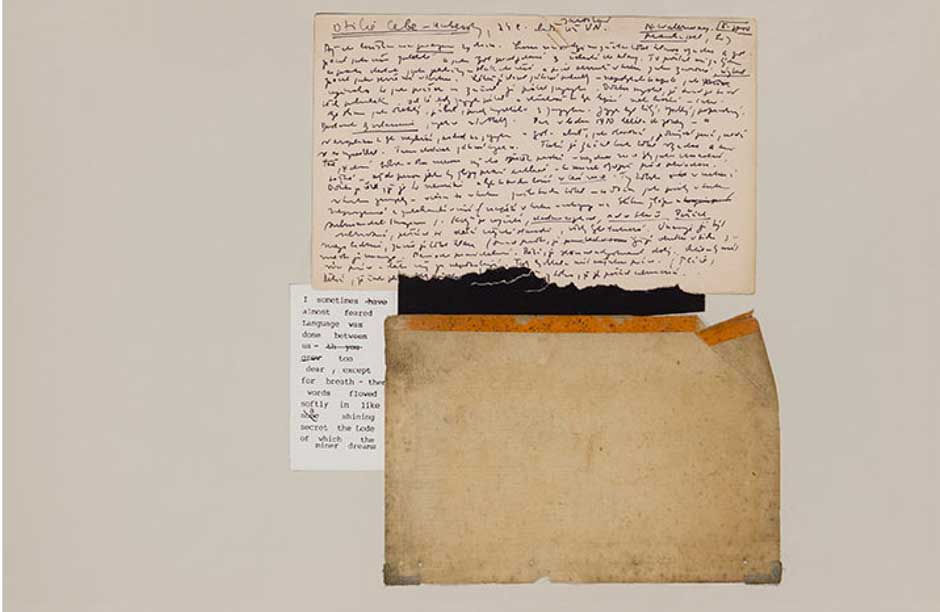

Janet Malcolm’s fifth solo exhibition at Lori Bookstein Fine Art is called “The Emily Dickinson Series,” a collection of collages assembled with construction paper, glassine, charts, photographs, and shards of poems. The collages were inspired by Marta Werner’s book, Emily Dickinson’s Open Folios: Scenes of Reading, Surfaces of Writing, which pairs images of Dickinson’s late scraps of paper—thought to be drafts of love letters—with typewritten transcripts on the facing page. In a correspondence printed in Granta, Malcolm wrote Werner to ask if she might buy a copy of the out-of-print book; Werner responded that she seemed to have only one copy left herself, but that she would be happy to send it along as a gift. Malcolm, staggered by Werner’s generosity, accepted and sent her a copy of her own book of art photographs of burdock leaves, Burdock, as thanks.

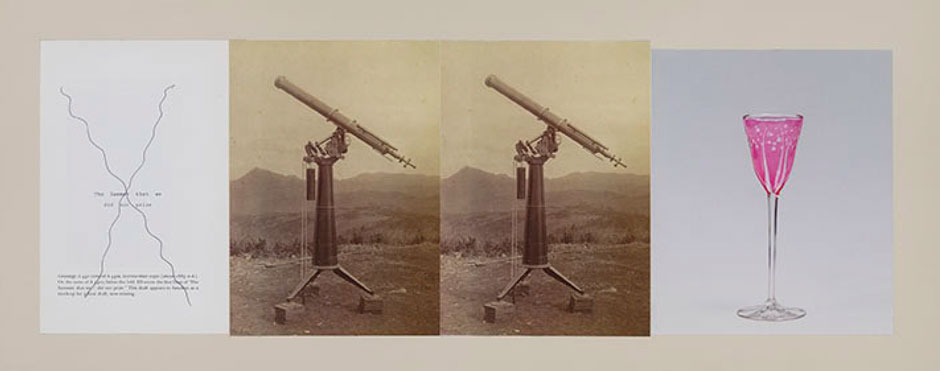

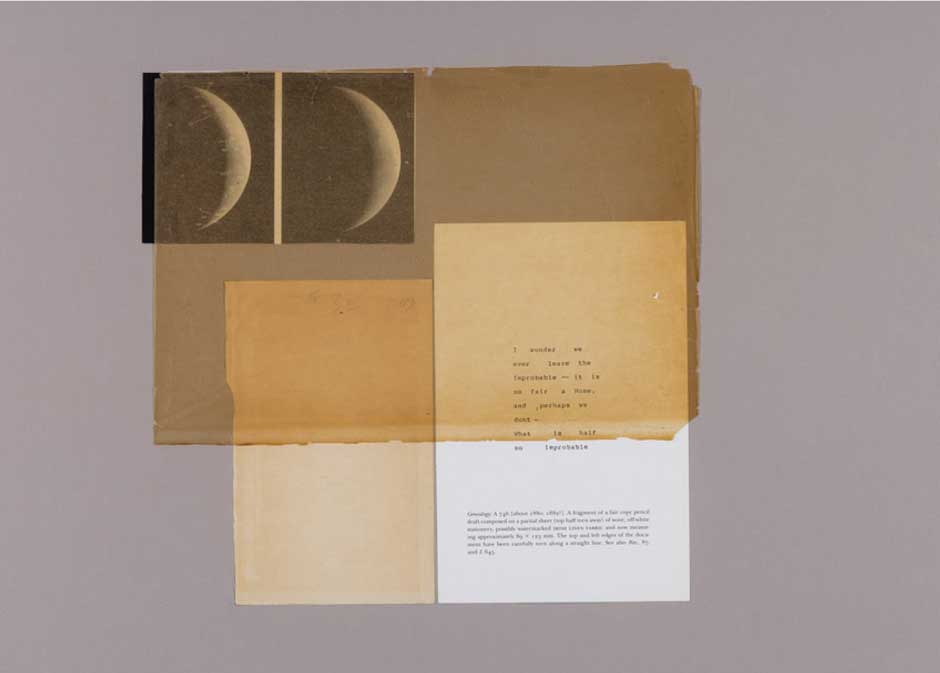

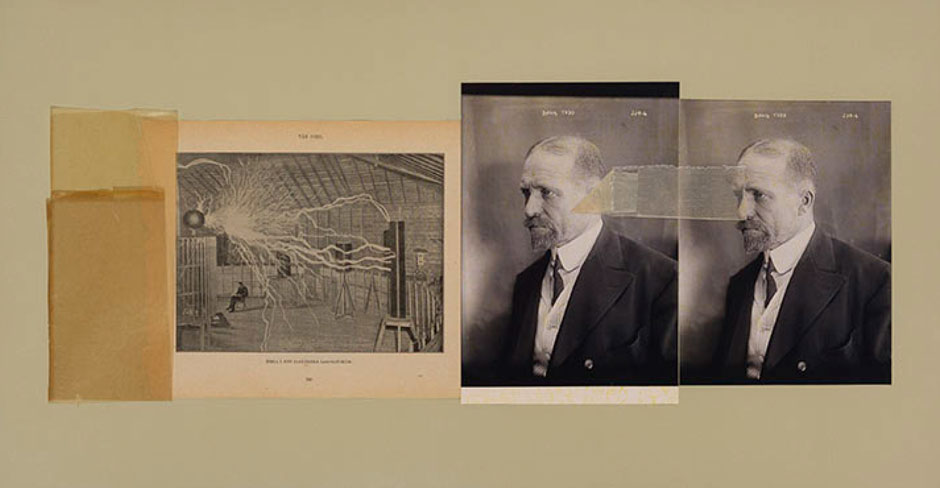

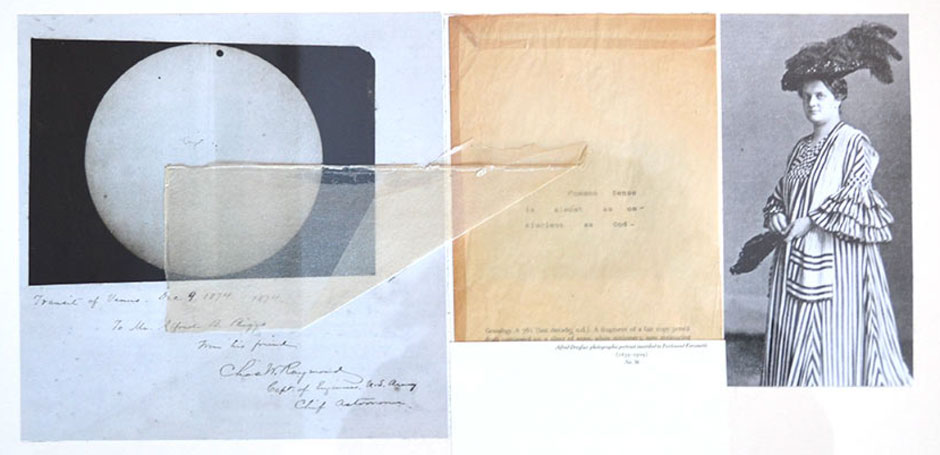

Malcolm and Werner were both surprised by how quickly their conversation became personal—the exchange is absorbing, and, as they quickly agree, uncanny. After receiving Werner’s blessing to use her book for collage, Malcolm soon sent her photographs of the first of the works, in which she had set Werner’s typescripts alongside, among other things, pages from an astronomical book, The Transit of Venus, 1631 to the Present. Yet unbeknownst to Malcolm, one of the scientists whose somber portrait she had included in her collages—an astronomer called David Peck Todd—was married to the woman responsible for the posthumous publication of Dickinson’s poems, Mabel Loomis Todd. Mabel Todd, for her part, had carried on an affair with Austin Dickinson, the poet’s brother. Werner thought Malcolm must have known this. Malcolm ends the correspondence with the question, “But what are we to make of my NOT knowing?”

Both Malcolm’s writing and her collages are preoccupied with what happens on the margins of knowing, or in its wake. Malcolm has always had great confidence in what she’s come to know—she writes with such a sure hand—yet at the same time she is well aware of the limits of what we might ever feel assured in saying. In “A House of One’s Own,” her essay on Bloomsbury, she writes that “we have to face the problem that every biographer faces and none can solve; namely that he is standing in quicksand as he writes. There is no floor under his enterprise, no basis for moral certainty.” The abyss is there and she nods at it and goes about her business.

It seems right, then, that Malcolm would be drawn to Werner’s attempt to translate the obscurity and idiosyncrasy of Dickinson’s hand into the ostensibly neutral forms of an old machine. She has, in turn, set Werner’s typescripts—with their detailed, academic captions—against imagery related to the opposite process: examples of how crystalline certainty (in this case, the scientific kind) decays with the passage of time into something altogether messier.

Many of the images are overlaid with folded and torn strips of yellowing glassine, the thin transparent paper used as a preservative cover in archives; here it preserves nothing, has itself become archival. Other collages feature matters of accounting—a mileage chart or a dry-cleaning ticket—now freed of the burden of use. After enough time, these collages imply, even something as dry as an actuarial table takes on the air of the recondite. This is especially true of superseded science. It once seemed so clinical, so controlled, and now appears so representative of the fashions of an era. A recurring image is a telescopic photo of the 1874 Transit of Venus: tiny black circles on large white ones, the beautiful form of an obsolete technology.

Malcolm’s collages, with their tears and seams and allusive overlaps, seem almost explicitly designed as companion pieces to the sure-handedness of her writing. They are, after all, made of cut-up books.

“Janet Malcolm: The Emily Dickinson Series” is on view at Lori Bookstein Fine Art through February 8.