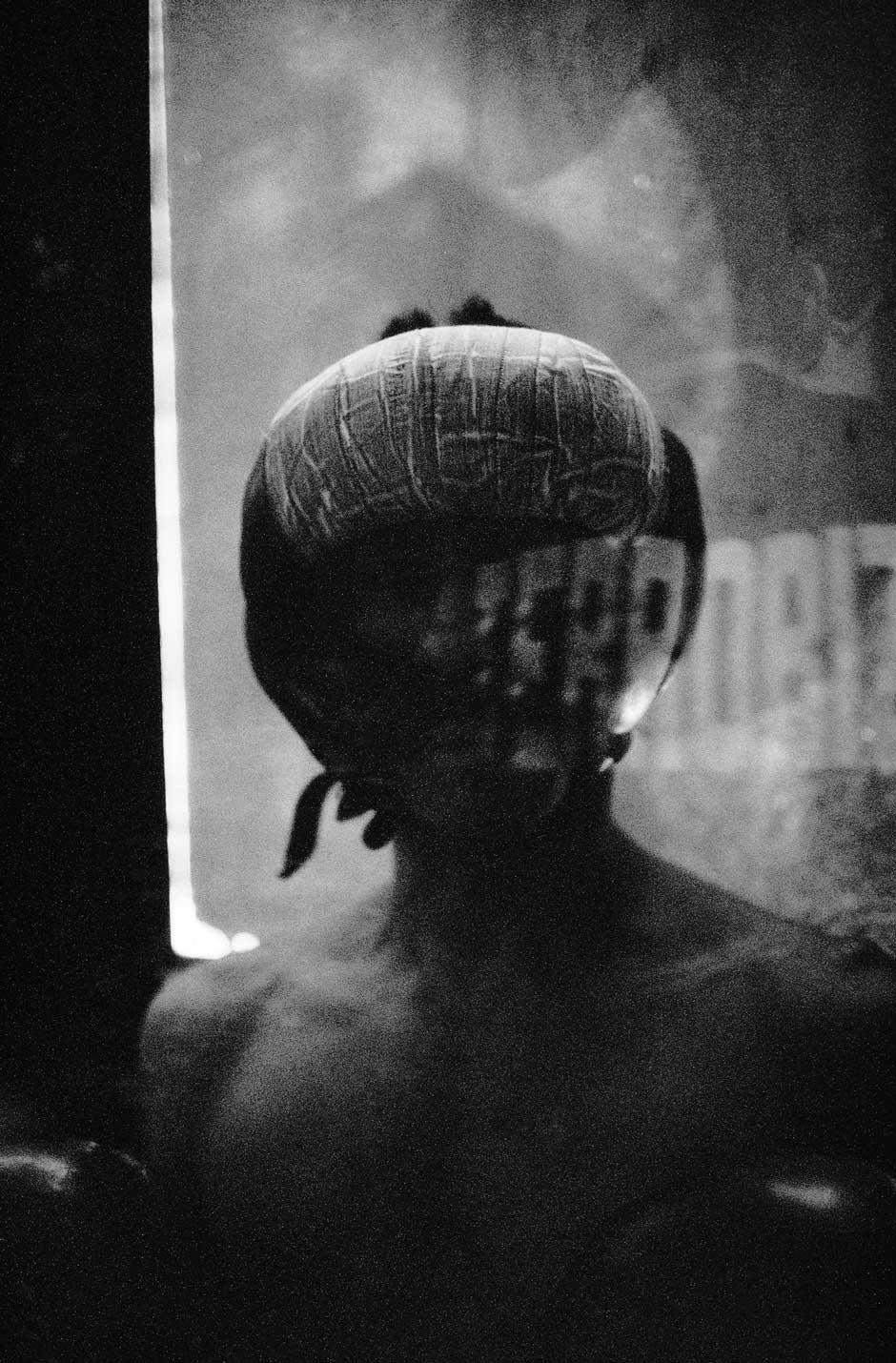

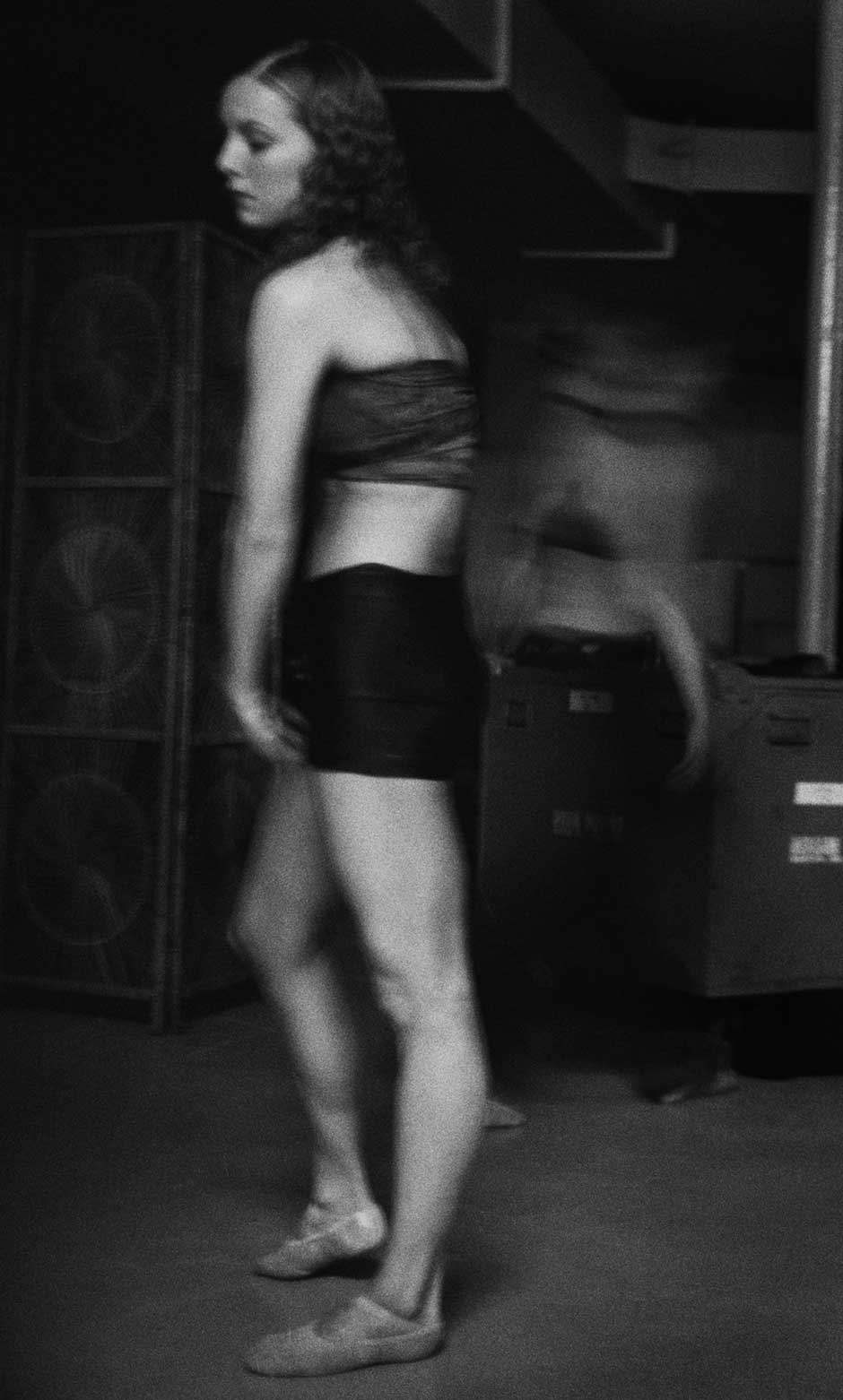

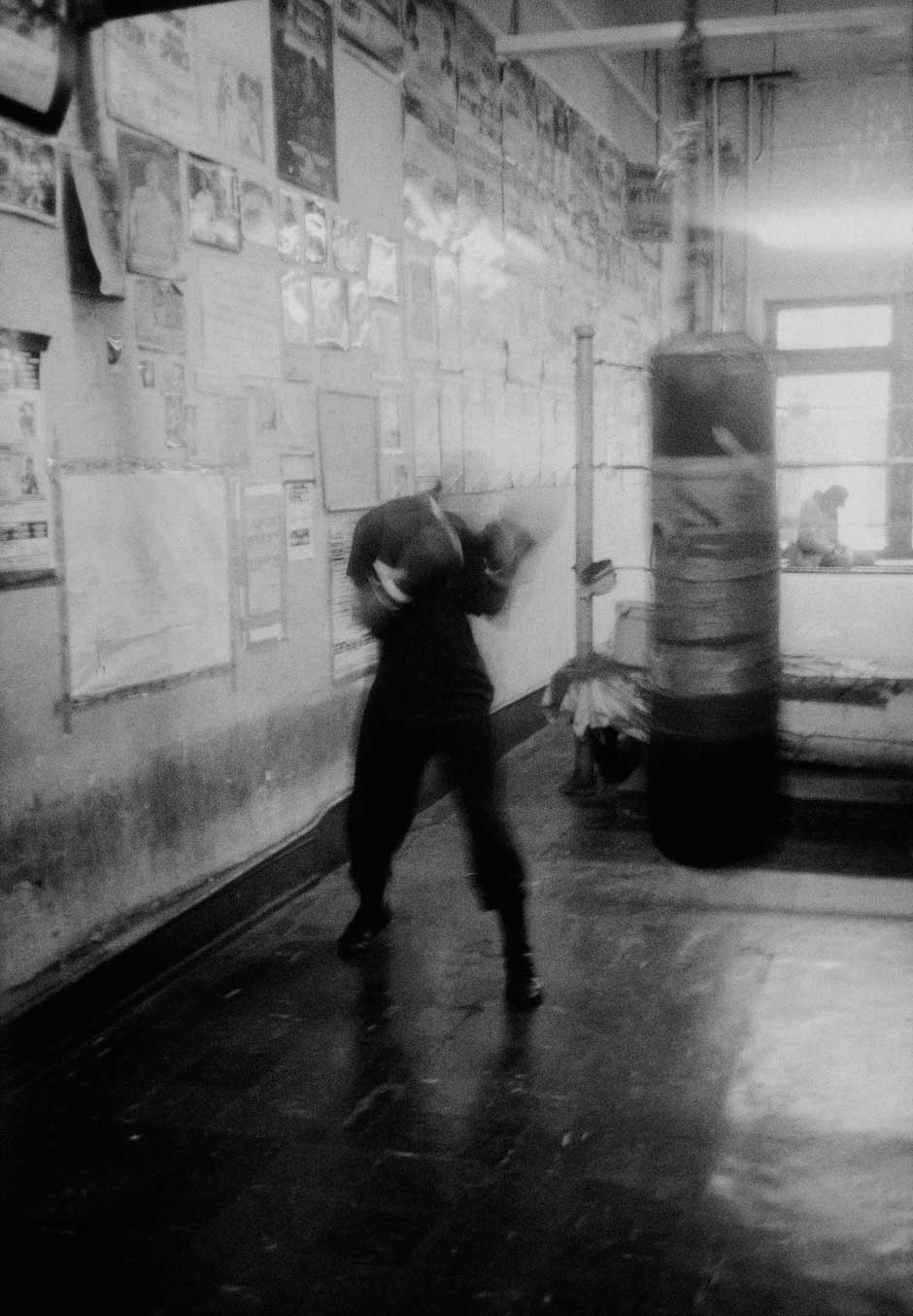

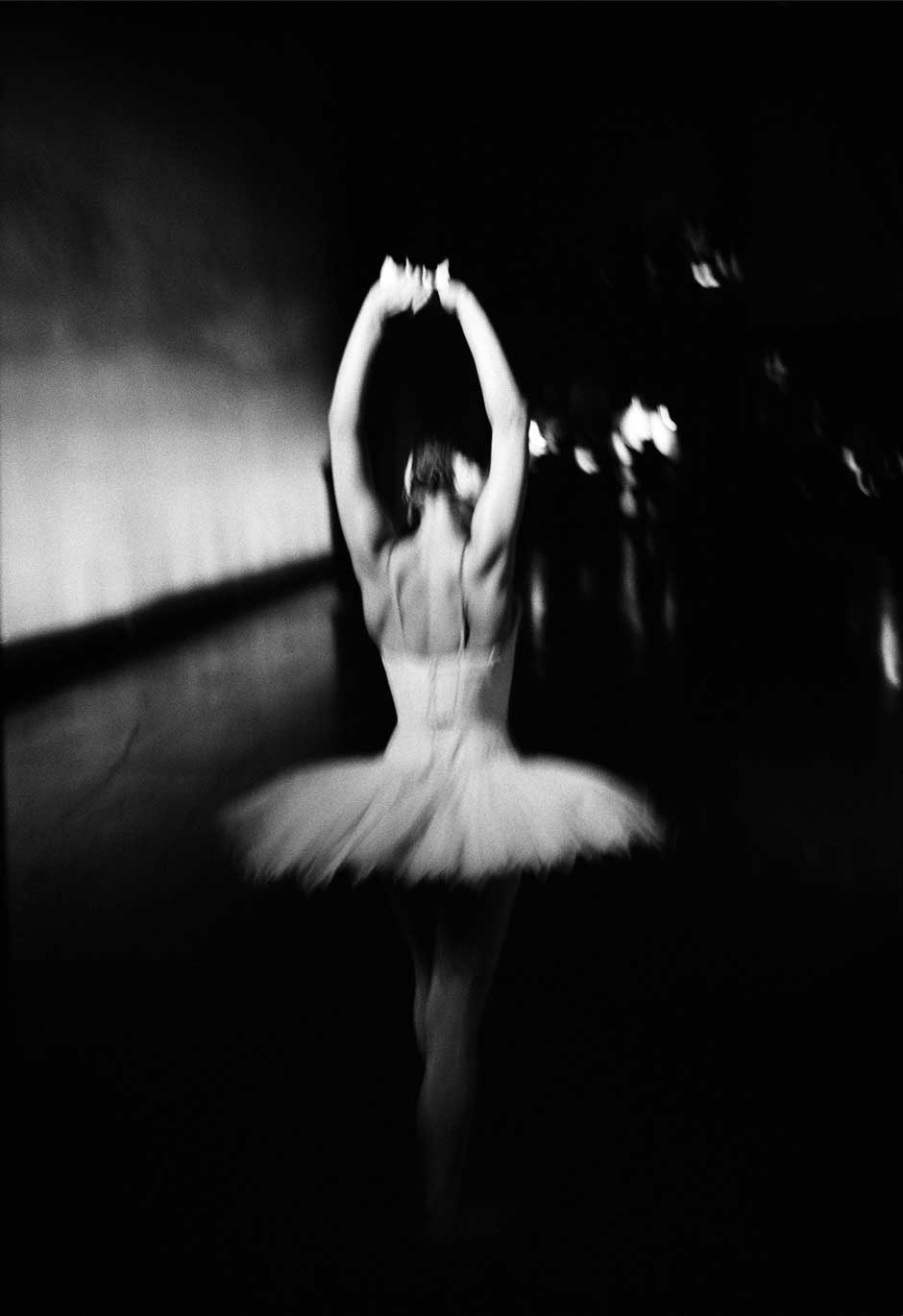

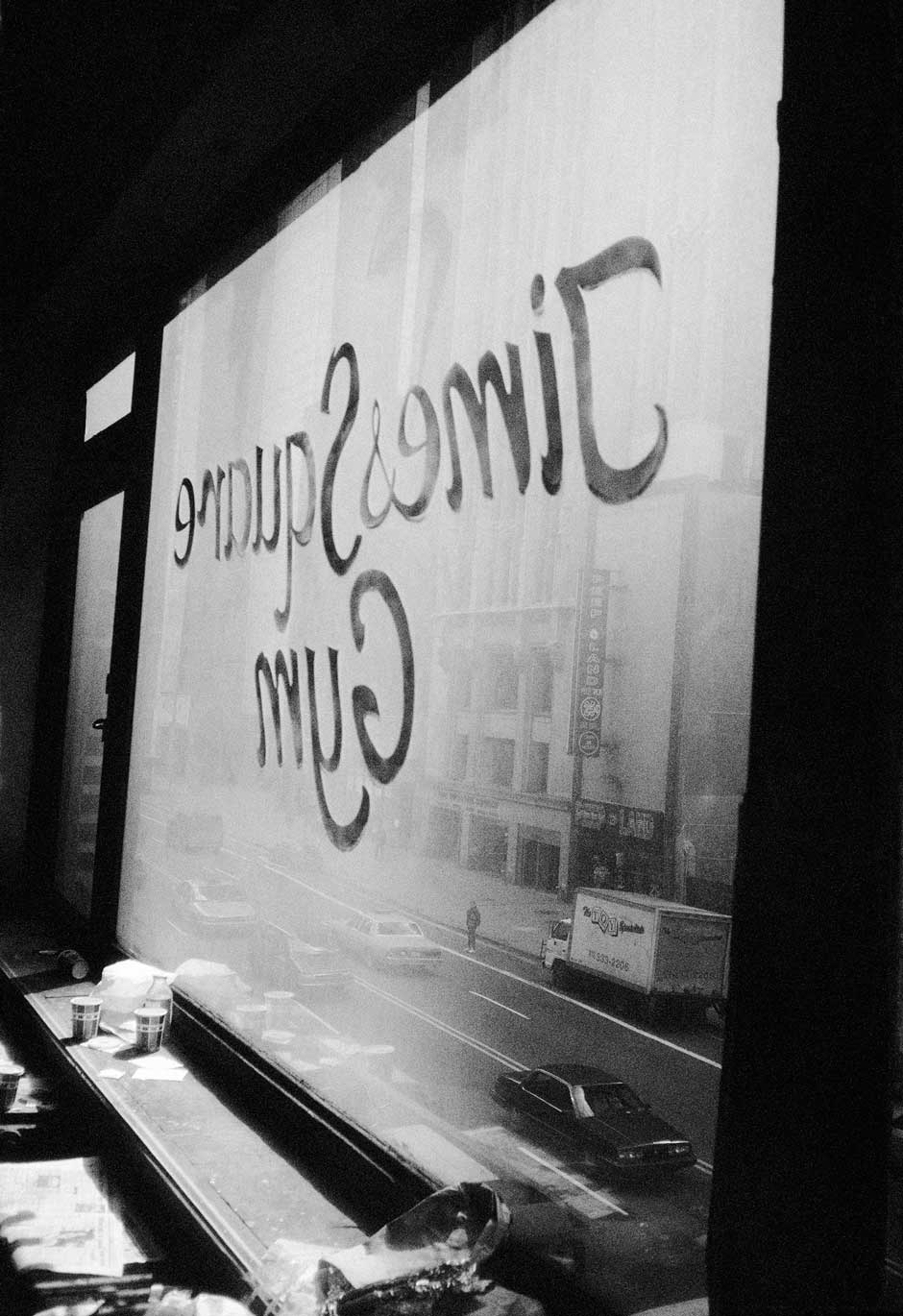

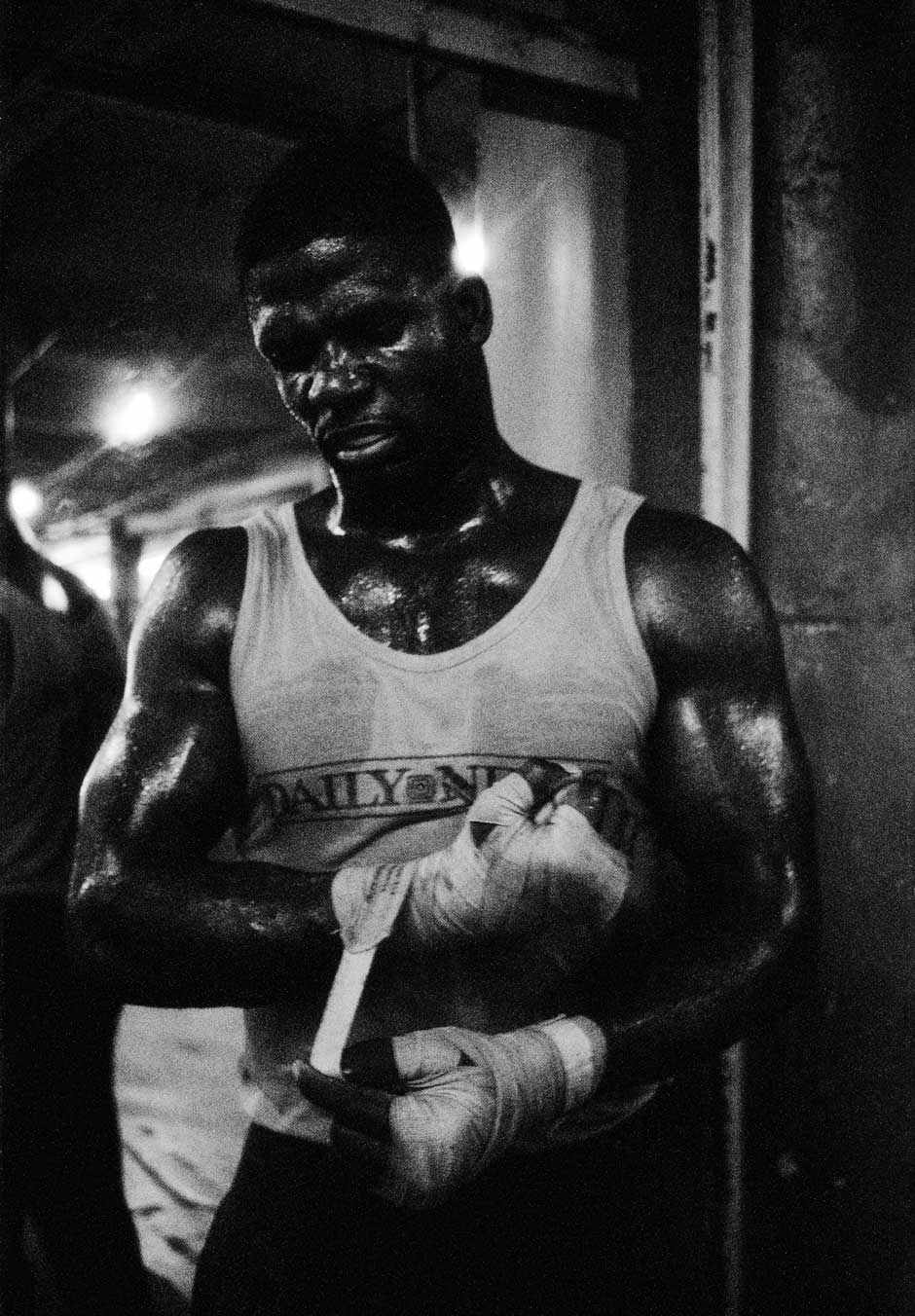

Together at last. Boxers and ballerinas. Those two great seemingly Yin-Yang forces of the physical—the soft, fluid Terpsichore and the aggressive Herakles; the small (ok, tiny) and the large (ok, huge); the artist and the athlete; the aerial and the earthbound. Too often ballet dancers are paired with flowers and satin in a pastel romanticization of what is, in truth, an uncompromising art, the most demanding on the body of all artistic pursuits. Boxers, meanwhile, are reduced to their swollen eyes, flying sweat, pooling blood, and heaving torsos. But in John Goodman’s first solo exhibition in New York, he juxtaposes beautiful black-and-white images of both—his photographs of dancers of the Boston Ballet taken in 2004 alongside his photographs of boxers taken at the famed Times Square Gym in 1996. We can now see the many similarities between these sylphs and gladiators—and each takes on a new clarity.

As a former ballet dancer I have never liked photographs of my profession that are blurred, time-lapsed. I understand the implied whirring speed of the action, the decision to emphasize the transitory nature of the art, but it is too frequently sentimental, focusing on the translucent chiffon wrappings while avoiding the body of steel inside, softening an art comprised of infinite sharp edges, so brutal in its demands as it reaches for the divine. To commemorate an art of do-or-die such images seemed sorely lacking—until I saw Goodman’s black-and-white shadowgraphs, which somehow manage to contain frozen precision with applied speed. The result is, as for his boxers, a rendering of something far grander, and closer to the truth.

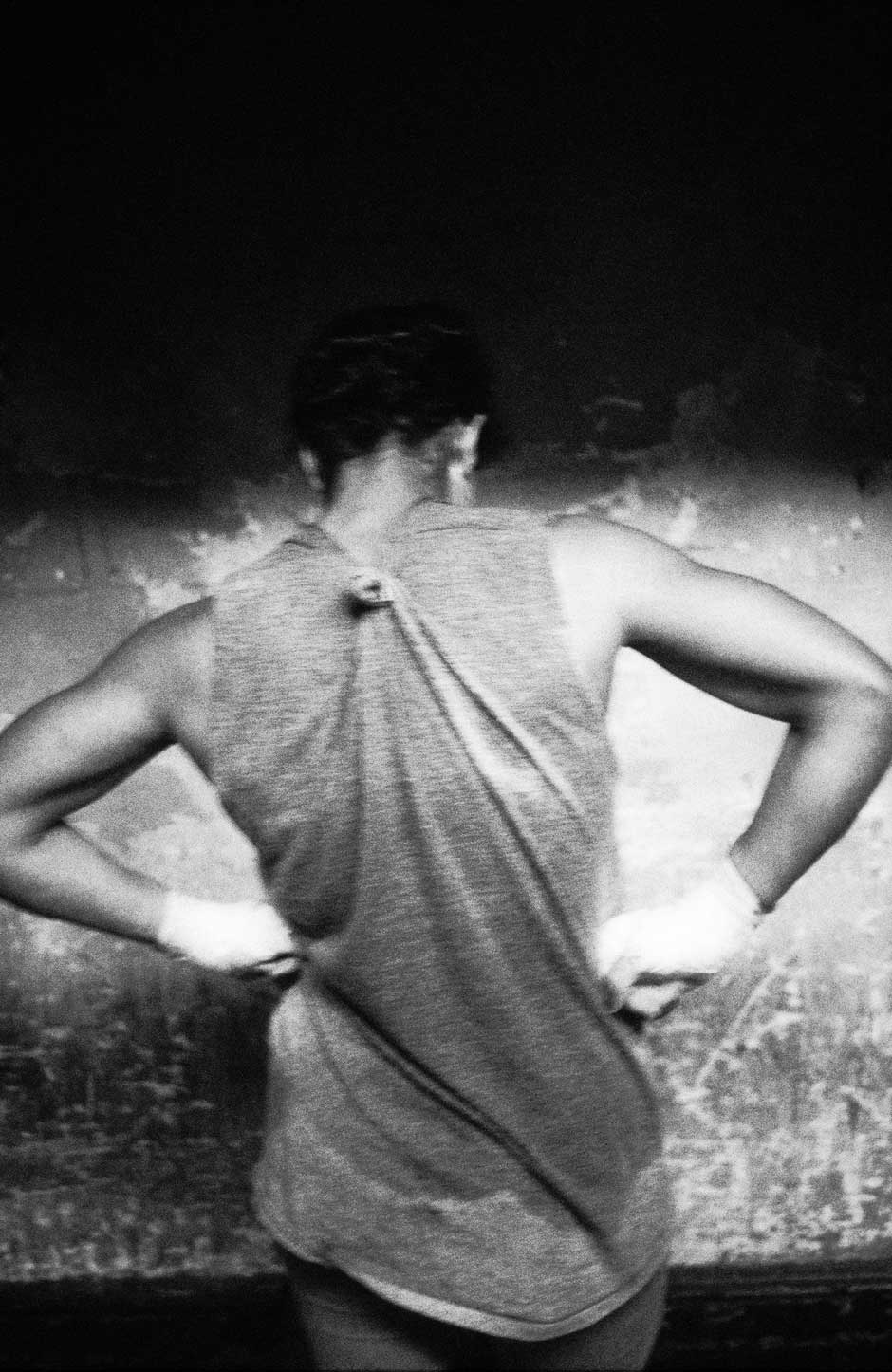

Goodman’s images do not capture the public moments of victory and applause, but he goes backstage with his subjects—the gym and the stage’s wings—and his view would seem so intimate as to be voyeuristic, were it not for his evident respect, even awe. Dancers and boxers are both in some sense physicalizations, outer echoes of the innermost reaches of mental discipline, the pride and grit that help produce the highest efficacy of movement in the shortest space of time. Ballet and boxing are non-verbal, highly hazardous professions with short-lived careers. They are thus irrational pursuits and often appeal to children from working-class backgrounds, offering a chance to get out, to go forward, to make a name and an unlikely life.

It is worth noting that, while ballet is an aristocratic art form founded in the courts of kings and tsars, it has, historically, almost never pulled its actual professionals from the rich or educated. Rudolf Nureyev, for instance, was born on a train, and raised in a small Russian village where his family was so poor they subsisted mainly on potatoes. As a child, he had no shoes to wear to school. Suzanne Farrell was born in Cinncinnati, one of three girls of a single mother, a nurse. She lived in one room when first in New York, rotating time in the bed with her mother and a sister, while eating at the local automat. Both boxing and ballet at their highest, so impossible in their respective aims, attract those willing not only to work hard beyond all decency and comfort, but who have the hunger of sheer survival.

In his essay accompanying the exhibition’s catalog, The Times Square Gym, the journalist Pete Hamill explains that the “mysterious quality” that motivates boxers is not merely “courage,” but rather “the willingness to endure punishment in order to inflict it.” Dancers, likewise, “endure punishment” in order to create beauty.

Goodman’s photographs capture both dancers and boxers stretching, crouching, gazing exhausted into space, fixing shoes and gloves—those respective curiosities that both protect their wearers at their crucial points of contact, while enabling them to blast through the barriers of gravity, of flesh, in their momentary spurts of exertion.

But to me, Goodman’s portraits are most moving in their depiction of the sheer loneliness of the parallel, unwinnable fights of self against two inhuman opponents: gravity and time.

“Boxers + Ballerinas” is on view at Rick Wester Fine Art from April 3 through May 31, 2014.