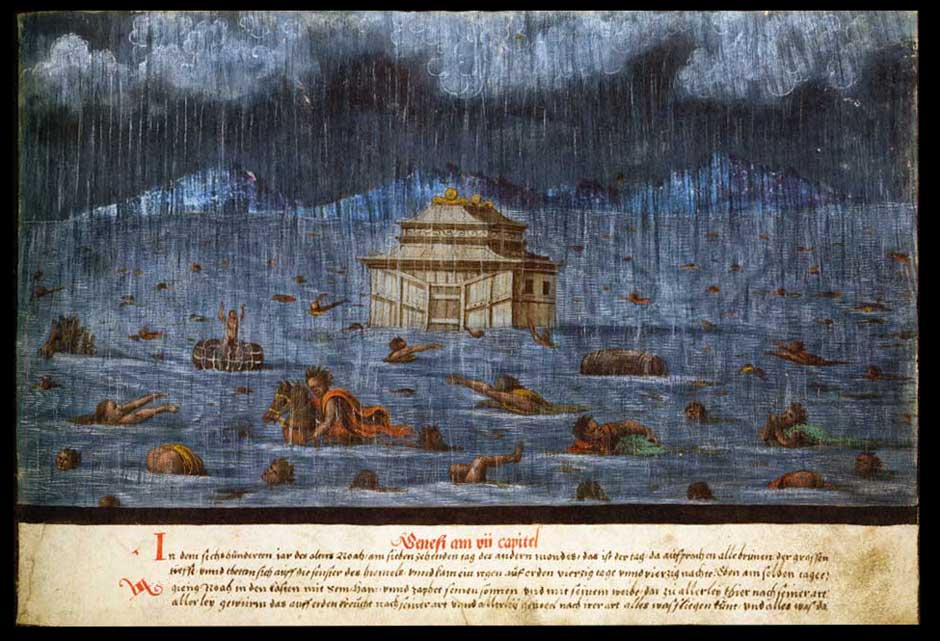

Signs and wonders manifest God’s irruption into the human world: when the Israelites flee from persecution in Egypt, the Red Sea heaves up in a great tsunami, parts to let them through safely, then closes over the Pharaonic army in hot pursuit. Wonders wrought by God take the form of miracles, events which overturn the natural course of things: water gushes from the rock when Moses strikes it to stave off thirst, and manna falls from heaven to feed the fugitives in the stony desert. These are signs of divine mercy to his chosen people. But the God of the Old Testament is also angry and the cosmos he created reflects his moods; in flood, famine, and plague, the universe gives warning of the penalties for straying from divine law, or inflicts punishment directly on wrongdoing. Signs of divine vigilance are above all meteorological: in Genesis, Yahweh is angered by human delinquency, and sweeps away his creatures in the deluge, except for Noah and his family and animals selected for breeding. In the Second Book of Maccabees, an angelic host “riding horses with golden bridles” appears in the sky above the battle to help the Jews’ resistance.

The New Testament continues the sequence of divine messages transmitted in celestial phenomena. Eclipses, like comets, are charged with foreboding. When Christ is dying on the cross, darkness falls at noon, as prophesied in the Book of Isaiah. The closing book of the Christian Bible, Revelation, or the Apocalypse of Saint John the Divine, seethes with prodigious omens: in a violent tumult, visions of monstrous beasts and other wonders—Death on a pale horse and the woman clothed with the sun—follow pell mell, forming one of the most powerful texts ever created about divine intervention. All the riotous meteorology in the Apocalypse signifies acts of providence. Nothing is as it seems; deep meaning is encoded in the fire that falls from heaven, the lamb, the locusts and dragons and frogs, and the seven-headed beast.

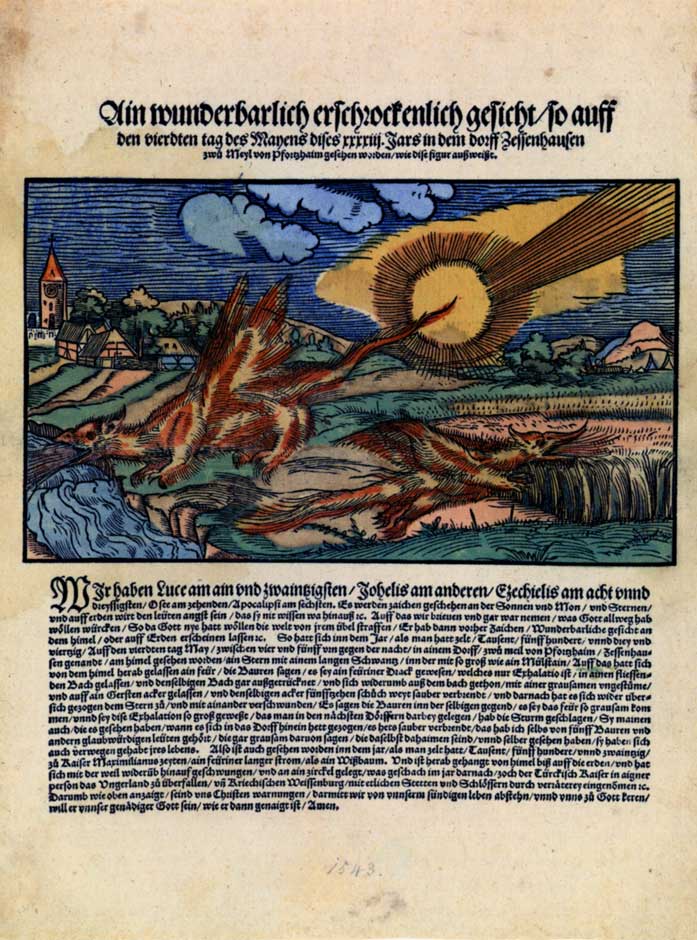

The recurrence of miracles in the Bible meant that the Protestant reformers of the sixteenth century could not reject such wonders as superstitions in the way they scorned Catholic beliefs. Such practices as the cult of relics and the use of icons and indulgences did not have, the reformers argued, corroboration from scripture. By contrast, basing himself on his deep reading of the word of God, the radical reformer Martin Luther believed in portents and their warnings, fearing the end times coming; he set an example to others. Philip Melanchthon, his friend and co-reformer, was also alert to signs from heaven; in austere Zurich, the sixteenth-century Zwinglian clergyman Johann Jakob Wick filled twenty-four albums with reports of such wonders in broadsheets and pamphlets. These men saw God’s calls to the sinner to repent in the birth of a monstrous two-headed calf or an unfortunate, flipper-handed infant.

Such interpretations are morally repugnant to us now as well as startling for intellectual reasons. Augury is generally associated with pagan antiquity, when the priests of the state haruspicated, or consulted omens by other methods. It is more usual today to think of the Reformation as inaugurating a modern attitude and setting aside the credulity of medieval Christianity, rather than perpetuating the world views of a pagan past, when the future was divined from the flight of crows, or the quivering innards of a sacrificed animal. But the new focus on reading the Bible led to a resurgence of interest in stories of direct divine intervention, and Protestant Europe in the sixteenth century saw a “boom” in compendia of miracles, among them The Book of Miracles, a luxury manuscript produced in the Imperial City of Augsburg and only recently rediscovered.

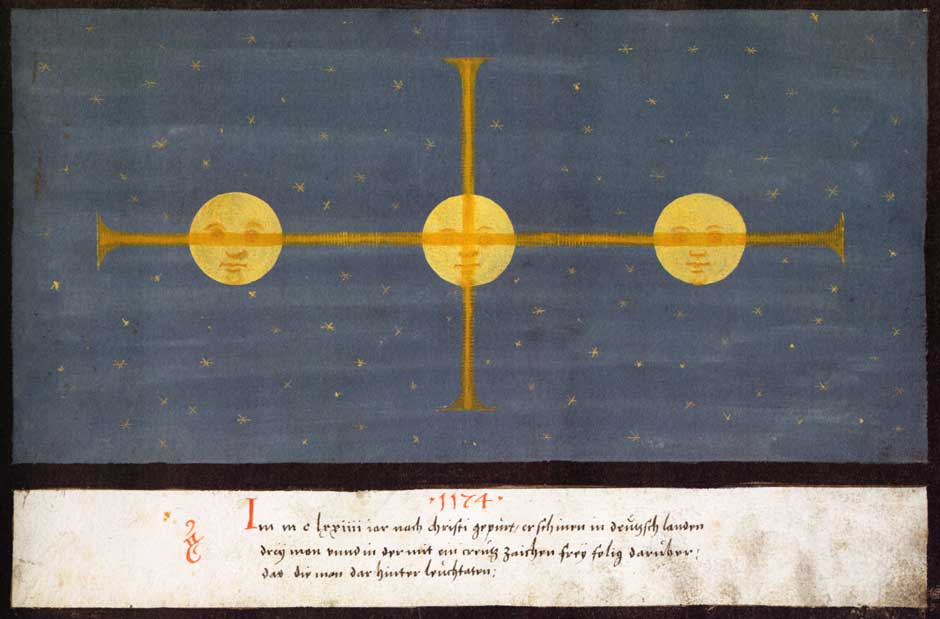

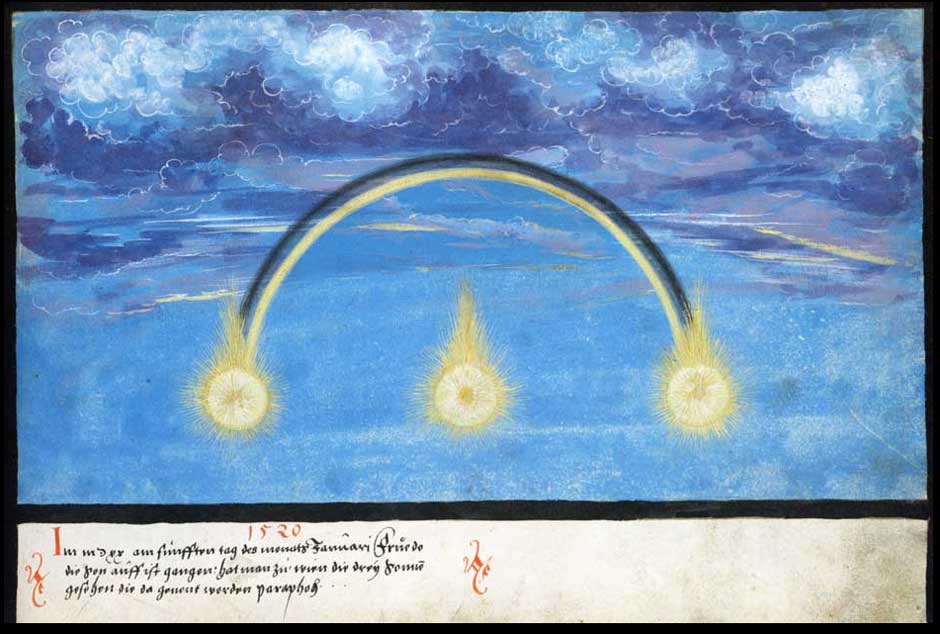

The Book of Miracles unfolds in chronological order divine wonders and horrors, from Noah’s Ark and the Flood at the beginning to the fall of Babylon the Great Harlot at the end; in between this grand narrative of providence lavish pages illustrate meteorological events of the sixteenth century. In 123 folios with 23 inserts, each page fully illuminated, one astonishing, delicious, supersaturated picture follows another. Vivid with cobalt, aquamarine, verdigris, orpiment, and scarlet pigment, they depict numerous phantasmagoria: clouds of warriors and angels, showers of giant locusts, cities toppling in earthquakes, thunder and lightning. Against dense, richly painted backgrounds, the artist or artists’ delicate brushwork touches in fleecy clouds and the fiery streaming tails of comets. There are monstrous births, plagues, fire and brimstone, stars falling from heaven, double suns, multiple rainbows, meteor showers, rains of blood, snow in summer.

The editors of the facsimile, Till-Holger Borchert and Joshua P. Waterman, provide a detailed and highly expert commentary in English, French, and German. They relate this newly discovered manuscript to the cluster of apocalyptic albums that were compiled from the late 1400s onward, with enthusiasm cresting in Germany and Austria in the 1550s and spreading from those countries to France and Italy, often in vernacular versions or translations from the original Latin. Borchert, chief curator of the Groeningemuseum in Bruges, cites Alsatian humanist Conrad Lycosthenes’s Chronicle of Prodigies and Portents (l557), which was copied and translated many times; it seems to me, however, that the Histoires Prodigieuses of Pierre Boaistuau, which first appeared in Paris in 1560, offers the closest counterpart to The Book of Miracles. The copy in the Wellcome Library, London, shows a similar opulent sensuousness in its richly coloured illuminations to the Augsburg manuscript. There are conceptual differences, however: Lycosthenes and Boaistuau evince a curiosity that is primarily scientific, not theological. Both were motivated by a proto-Enlightenment desire to know and understand, the same motives that spurred on collectors of Wunderkammer, rather than religious fear and trembling. The Augsburg Book of Miracles combines both strands a bit uneasily: pious episodes from the Bible are mixed with dazzling, bold paintings that could have come from a scientific treatise on astronomy.

Advertisement

Each scene is identified in a caption written in German in spiky Gothic script, giving the Biblical source, or the date and place of the historical event. But, as Waterman points out, while the standard formula for illustrated broadsheets contains a description of the event, an interpretation, and a warning to the faithful, “the last two elements—interpretation and moralistic admonition—are almost completely absent from the Augsburg Book of Miracles.”

In other respects, especially iconographic, the images of the Augsburg book frequently follow contemporary models, such as the widely disseminated Luther Bible of 1545, very closely indeed, as if the artist or artists were working from engravings or broadsheets in circulation, or had seen one of the illuminated manuscripts that likewise gathered together stories of supernatural activity, such as Ezechiel’s ascent into heaven in his fiery chariot, borne up by whirring wheels of cherubim, each of them with four faces.

There are no photographs given here of the book as an object in itself. The leaves were rebound in the nineteenth century, we are told, and some are missing from the sequence, with one or two recently traced. Only the rectos are filled with the paintings, the versos are blank, their discoloration faithfully reproduced. To my eyes the page layout strongly recalls ex voto plaques, which are made to be hung against the walls of a shrine. These usually depict accidents averted by the grace of a saint or the Madonna—the intercessor to whom the shrine is dedicated and who often appears in the image, hovering in the sky above the scene of the near catastrophe. Such images have intense human interest, but this is missing from the miracles in the Augsburg codex; its author(s) are chiefly absorbed in chronicling extreme weather, and, in some of the ravishing compositions, showing triple suns and meteor showers, in freak effects tending to the sublime.

The manuscript is something of a prodigy in itself, it must be said: its existence was hitherto unknown, and silence wraps its discovery; apart from the attribution to Augsburg, little is certain about the possible workshop, or the patron for whom such a splendid sequence of pictures might have been created. The name of the Augsburg artist and printmaker Hans Burgkmair appears on folio 117r, on the page illustrating the birth of conjoined calves, and Borchert consequently proposes that, as Burgkmair the Elder died in the 1530s, the artist in question here must be his son, Hans Burgkmair the Younger, who is much less well attested by known works. But all in all, this Book of Miracles is a gorgeous unheralded surprise: a foundling of unknown parents, a virgin birth.

The Book of Genesis gives specific measurements for the construction of the Ark, and inspired models and images that attempted to reproduce the vessel as described. The artist of the Augsburg Book of Miracles adds fanciful upper stories to his contemporaries’ printed illustrations of the scene (cf. folio IVv from the Luther Bible, printed in Wittenberg in 1534), against a dramatic, moody background characteristic of his vision and his palette.

The inscription quotes the Book of Exodus, and the artist has taken the scriptural passage literally: “…the people of Israel walked on dry ground through the sea, the waters being a wall to them on their right hand and on their left.” As is the tradition in religious painting, the Jews are dressed in the fashion of the good burghers of sixteenth-century Augsburg, while Moses, leading the flight to safety, wears prophetic horns on his head and has prepared for the crossing by taking off his shoes and stockings. The scrolling lines on the huge waterspouts are pleasingly light of touch and quick with energy, and a feature of this artist’s best work.

Advertisement

The word, comet, comes from the Latin for hair, comes, and the tails of meteors as they streamed through the sky were imagined to be golden hair like the goddesses’ in Homer. This gorgeous portent, richly pigmented in thick gamboge yellow and paler primrose gold, against a star-flecked grey-blue night, was reported to appear at the time of Muhammad’s birth over the city of Constantinople.

Three moons, linked by a golden cross across their faces, show the artist’s gift for striking simplicity. The portent was seen in Germany in 1174. With examples such as this rare, indeed extraordinary meteorological wonder, the author’s reticence can be frustrating. How was it interpreted at the time? What did those who first saw it feel, and had its meaning changed for his contemporaries by the sixteenth century?

This marvellous hybrid was left stranded and dead after the flooding of the river Tiber in 1496 subsided. Like medieval images of the Devil, the creature’s form is ambiguously male and female, reptilian and mammalian; news of its appearance circulated in broadsheets, and became notorious after the reformers adapted the image to represent “the Papal Ass,” agent of the evils of the Church of Rome. But to modern eyes, trained by Surrealism, this monster has an appealing fancifulness, not so much threatening as comic.

Three suns rose over Vienna on January 5, 1520, within the living memory of people whom the artist might have met. The beautiful illusion created by the Parhelia phenomenon occurs in deep winter; as with the phenomenon known as Fata Morgana, bands of air in layers at different temperatures become mirrors, and multiply the reflection of objects on their surfaces.

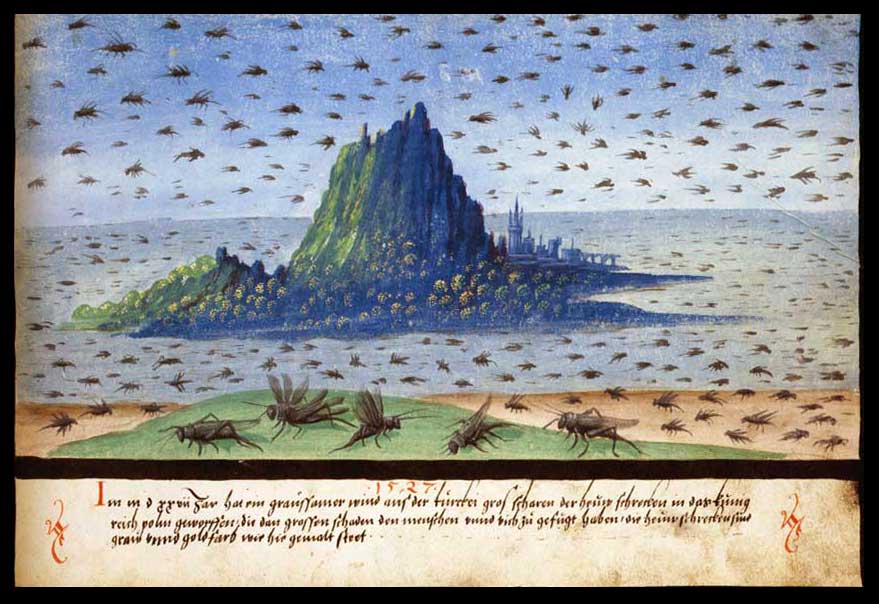

In 1529, a plague of locusts fell on Poland, carried on the wind from Turkey: “They were grey and gold color, just as is painted here,” says the caption. The huge insects, rendered in translucent close-up in the foreground, add a vivid touch of horror.

In 1531, around two hundred years before the terrible earthquake in Lisbon, which galvanized Voltaire’s revolt against the idea of Divine Providence, the city was shaken and “more than a thousand people killed.” The inscription says that a whale was seen in the sky, along with streaks of blood, but in the picture the beast rages in his more natural element.

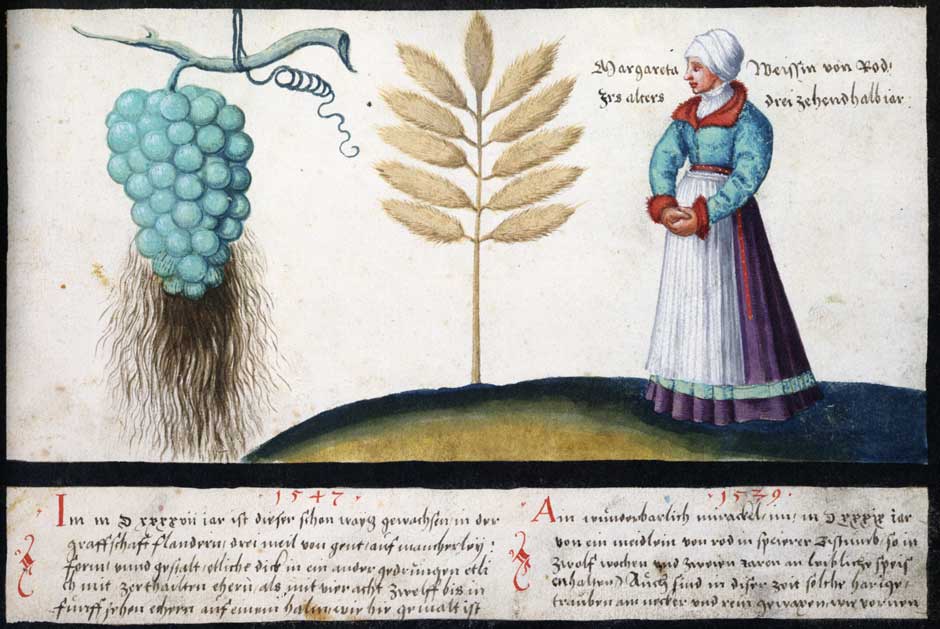

Cabinets of curiosities, the museological equivalent of books of wonders and marvels, eventually evolved in into the freak shows and amusement parks of modern entertainment, as in Ripley’s Believe It or Not! sideshows. Bearded grapes, supersize wheat, and fasting girls were favorites with collectors of mirabilia. This young woman depicted here “who did not eat for two years and twelve weeks” was called Margaretha Weiss, aged thirteen and a half, from “the diocese of Speyer.”

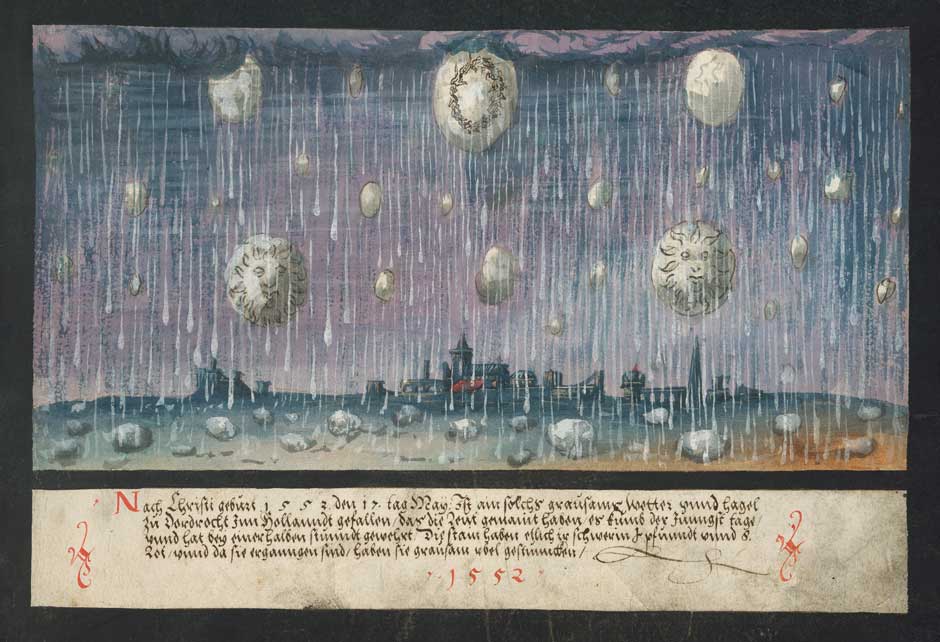

This tremendous picture of a hailstorm on May 17, 1552, over the town of Dordrecht, gives a terminus post quem for the manuscript, as it is the last dated wonder reproduced in the book. The subsequent pages depict scenes of divine retribution from Revelation; in this way reports of strange phenomena are firmly bookended by scripture, and the possibly profane appetite for bizarre and singular occurrences acquires a degree of legitimacy, being directed at the acts of all-seeing and all-powerful providence, and not at the marvelous vagaries of nature.