The Alaskan brown bear rises up as tall as a brownstone and claws the bright wintery diorama sky; the vultures and hyenas and jackals hunch and squirm hideously in the light of their glass case. But all around them is darkness. The rooms that hold the Museum of Natural History’s famous dioramas are vast and dimly lit. The dioramas themselves shine like stages in a darkened theater. It doesn’t feel like theater though. Even with the squalling strollers and teenagers whooping beneath the elephants and the echoes of half-hearted parental noes, the museum is a still place. I have always liked the darkest of the dark rooms best, the narrow hallway in the North American mammal section where ghostly wolves run stealthily through the night and spotted skunks stand on their tiny hands to wave their tails in the air. That hushed public place is the private secret of every child in New York, I think.

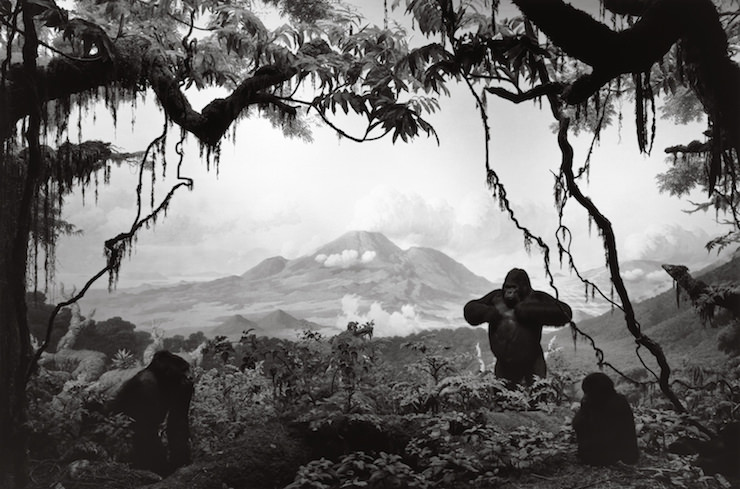

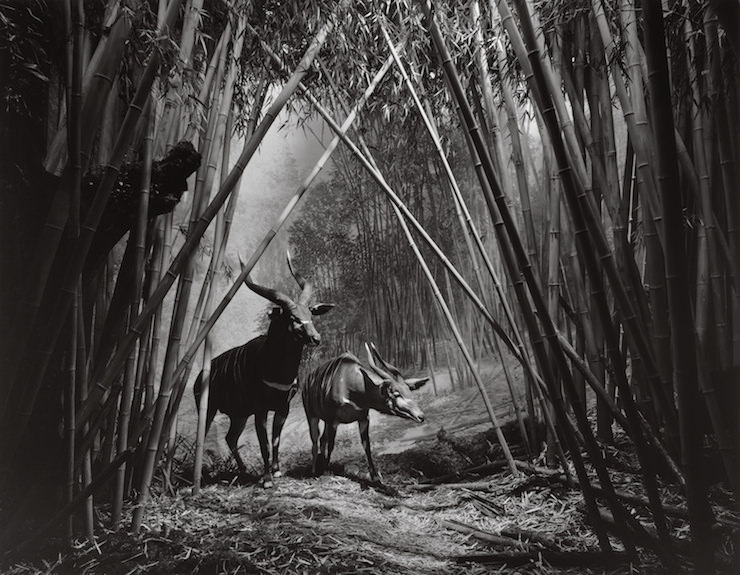

Perhaps the darkness struck me more than usual on a recent visit to the museum because I had just been looking at Hiroshi Sugimoto’s new book, Dioramas, a collection of his elegant black and white photographs of dioramas, many of which were taken at the Museum of Natural History. I saw Sugimoto’s work for the first time in person at the Getty this summer in Los Angeles—his photographs of historical figures created for him from Madam Tussaud’s wax museum—and was charmed and frightened and fascinated and finally deeply moved by the enormous, eerie images that were so real and so artificial and so beautiful. The portrait of Queen Victoria, stern and magnificent in her Silken Chinese costume, the Henry VIII modeled on a Holbein painting–-they were so explicit with their pearlized pearls and smooth fleshy skin that they seemed almost obscene. Sugimoto uses long exposures, and the feeling I got from his work is just that: of observing something being exposed, something normally hidden, buried, and the uneasy sense that perhaps it was meant to remain hidden, undisturbed.

The book with its smaller images is less intense. It’s harder to decipher the surprises and ambiguities in the photographs, but they’re there. The image on the cover of Dioramas is Sugimoto’s photograph of the polar bear looming above a seal that lies, oblong and fat, beside a crack in the pure white ice. The other day, a guest saw the book in my living room and said, “Oh, cute!” then, a quick double take as he noticed the droplets of blood: “Oh… dead.”

In the museum, with the dead original of the dead seal and its equally dead predator the polar bear, almost everyone of almost every age was taking pictures with their smart phones. The iPhone pictures come out with an old-fashioned technicolor richness, disturbing in their own right, but nothing like Sugimoto’s smooth white planes of light. Sugimoto is interested in the stillness of the images, in exposing that stillness and surprising us with what it really means: the passage of time, the stopping of time, death and the long history of life. In dioramas, he writes in the introduction to the book, “the only thing absent is life itself. Time comes to a halt and never-ending stillness reigns.” Which reminds him of mummies and Death Eternal. He has begun to collect fossils that, like photographs, are “able to stop time” and are “records of history.”

What happens in the darkness of the museum itself, and what is meant to happen, is quite different from Sugimoto’s stillness. It’s the stillness of the observer, not the dioramas, that feels important. The stillness, the darkness—they are the very opposite of exposure, they provide a kind of protection from the drama of the hungry mammals, from the violence of the scenes; and from the violence, too, of the human natural history giants who lived, and collected, before the dawn of environmentalism. These animals were hunted and shot and collected and stuffed and placed in their cases as confident trophies of the great diversity of the natural world. They are meant to be marveled at, that’s why they’re there. The conservationism of the generation that created the museum, men like John Muir and John Burroughs and Teddy Roosevelt, grew out of awe more than fear. Nature was not yet itself an endangered species, it was instead a glorious spectacle. That’s an illusion, no less than Sugimoto’s photographic illusions, but that’s what the museum’s darkness allows us to experience—that uncomplicated wonder, that innocence.

Advertisement

Hiroshi Sugimoto: Dioramas is published by Damiani and Matsumoto Editions.