The Ptolemies who ruled Egypt for nearly three centuries, from about 320 to 31 BCE, had a difficult dual part to play: that of Hellenistic monarchs, in the mold of Alexander the Great, and, simultaneously, Egyptian pharaohs. The founding father of their line, Ptolemy I Soter (“Savior”), a Macedonian general in Alexander’s army of conquest, secured rule over Egypt amid the confusion following his king’s death, crowned himself monarch in 306 BCE. But he bequeathed to his heirs—the fourteen other Ptolemies who would succeed him, not to mention several Cleopatras—a difficult demographic and geopolitical position. The Ptolemies’ palace complex, staffed by a European elite, stood in Alexandria, one of the world’s original Green Zones, a Greek-style city founded on a strongly fortified isthmus facing the Mediterranean. To the south, nearly cut off by the vast marshes of Lake Mareotis, lived most of their Egyptian subjects. Some scholars have reckoned the country’s ratio of Egyptians to Greco-Macedonians at ten to one.

The strategies by which the Ptolemies maintained power in this complex environment are vividly illustrated in “When the Greeks Ruled Egypt: From Alexander the Great to Cleopatra,” an exhibition at NYU’s Institute for the Study of the Ancient World through January 4. To wield sovereignty over both populations required ingenuity, adaptability, and, in the Ptolemies’ case, a willingness to adopt the customs of their Egyptian subjects. Their great hero and model, Alexander, had set the template for religious tolerance and cultural fusion, winning hearts and minds in 332 BCE with his participation in the cult of the Apis—an Egyptian deity, incarnated in a living bull, that had been mocked by other foreigners. The Ptolemies followed his lead, taking part in age-old pharaonic traditions even while preserving their European heritage. To suit their Egyptian subjects, they had their portrait busts carved out of native black basalt, adorned by the pharaonic nemes headddress and uraeus or rearing cobra circlet; to the Hellenes in Alexandria, they displayed their images in stark white marble, with curling locks bound only by the thin diadem that, ever since Alexander first wore it, signified enlightened Greek monarchy.

Exploitation of religious feeling was central to Ptolemaic rule; their queens were linked iconographically to Isis, Aphrodite, and Demeter, their kings to Horus, Ammon, and Zeus. Ruler-worship was more prominent in upper-Egypt than along the coast, where a sophisticated, Hellenized populace no doubt chafed at the notion of god-kings, but even Greek subjects were encouraged to regard the royal couple as avatars of the divine. A pedestal for a cult statue of Arsinoe II—the lovely third-century Ptolemaic queen whose portrait can be found on some of the coins in this show—bears a long inscription in hieroglyphics as well as a shorter one in Greek, the latter identifying, for Hellenic worshipers, the now lost statue as that of “Arsinoe Philadelphos.” (The epithet, “Brother-lover,” alludes unabashedly—perhaps insistently so—to the practice of incestuous sibling marriage that, in another concession to local custom, the Ptolemies instituted in the second generation of their reign.)

Religious traditions blended and metamorphosed all across the Hellenistic world; Phoenician Melqart merged with Greek Heracles, Mesopotamian Ba’al with Zeus. Egypt, however, was the primary laboratory for syncretic experiments. Ptolemy I, general under Alexander the Great and founder of the Egyptian dynasty, introduced an obscure deity he had learned of in Babylon: Serapis, a god who looked like Zeus but was said to embody the spirit of both Osiris, Egyptian god of the underworld, and the sacred Apis bull. Greeks and Egyptians could join together in the worship of such a god. Other innovations to be seen here include statuettes of Horus, a pharaonic deity formerly depicted as a falcon or bird-headed man, but now as a naked pre-pubescent boy, often shown holding a finger to his chin. Variously renamed Harpocrates, Khonsu, Harpre, or Somtus, even while remaining Horus in some essential part, this too was a god whom Egyptians and their Hellenic rulers could share.

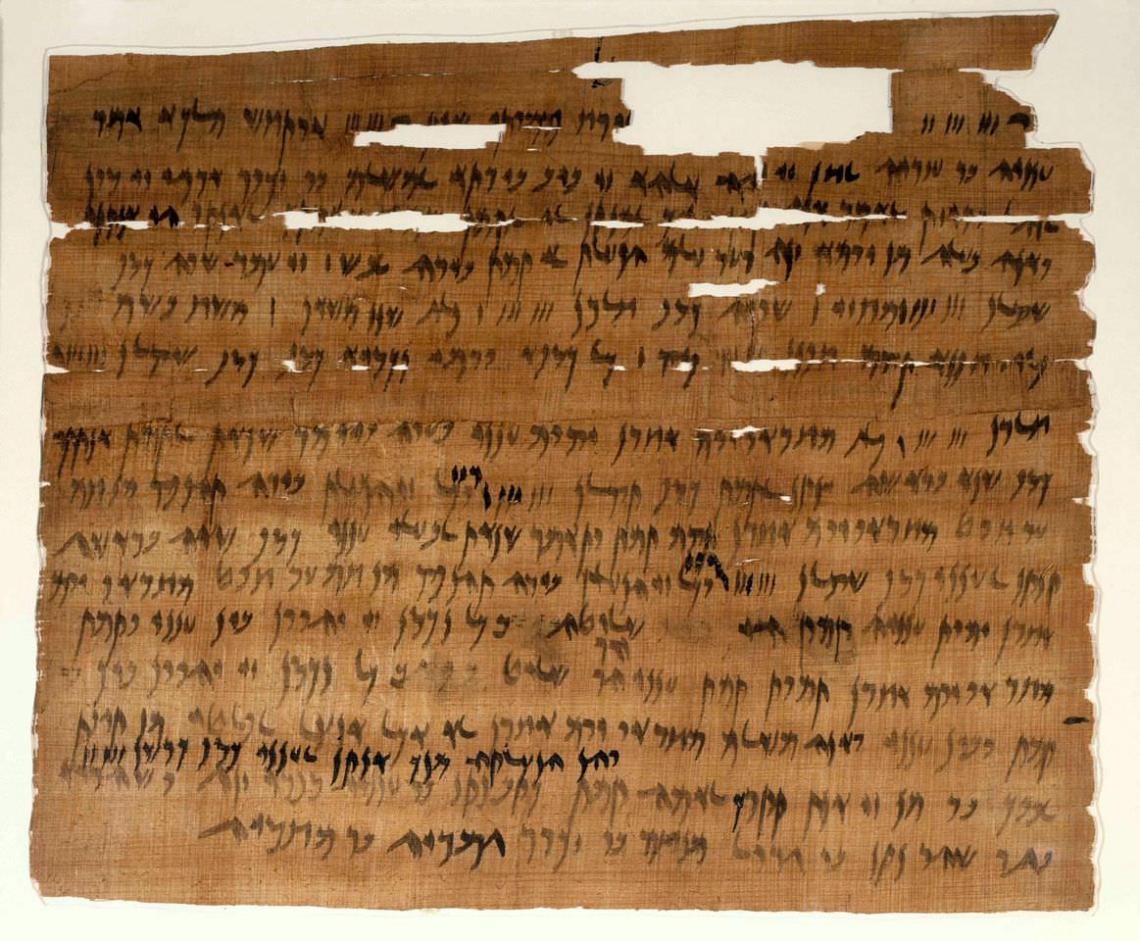

Egypt was a melting pot of languages as well as of religious traditions. Aramaic arrived in the sixth century BCE as the lingua franca of Egypt’s Persian conquerors, joining the Greek, Carian, and Hebrew tongues already spoken there by pharaoh’s foreign mercenaries. A superb set of Aramaic papyri displayed in this show provides a kind of biographic sketch of one Ananiah, a Jewish garrison soldier stationed at Elephantine (modern Aswan) who married an Egyptian slave named Tamet, acquired property, refurbished his home, and passed on his estate to his children, Pilti and Jehoishema. Though they precede the Ptolemies by a century, and have no connection either to the Greeks or their rule, these perfectly preserved documents illustrate one family’s journey through time in the polyglot, multiethnic valley of the Nile.

Advertisement

Ananiah lived in an Egypt that chafed under Achaemenid Persian conquerors who ruled from afar and disdained local traditions. Small wonder then that the Ptolemies, who made themselves at home in Egypt and embraced much of its culture, proved such a long-lived and successful dynasty, overthrown in the end not by revolt or rebellion but by the armies of the rising power of Rome.

“When the Greeks Ruled Egypt: From Alexander the Great to Cleopatra” is on view at NYU’s Institute for the Study of the Ancient World through January 4.