Lately, I’ve been reading Vanity Fair, and among the profound pleasures it provides is the mysterious, almost indescribable sensation of being alone with Becky Sharp and her coterie of unfortunate rivals and hapless admirers. Solitude is and has always been an essential component of reading; many children become readers in part to enjoy the privacy it offers. And in an age in which our email messages can be perused by the NSA and our Facebook posts are scanned for clues to our habits and our desires, what joy and a relief it is, to escape into a book and know that no one is watching. But now it turns out that someone or something may have been reading over my shoulder, that I haven’t been quite so alone as I’d imagined, that Becky and I and her circle may have had some silent, unsuspected, uninvited company.

Largely because I’ve been traveling, and because my volume of Thackeray weighs several pounds and is printed in a typeface that borders on the microscopic, I’ve been reading the novel on my e-reader. According to a recent article in The Guardian, e-book retailers are now able to tell which books we’ve finished or not finished, how fast we have read them, and precisely where we snapped shut the cover of our e-books and moved on to something else. Only 44.4 percent of British readers who use a Kobo eReader made it all the way through Donna Tartt’s The Goldfinch, while a mere 28.2 percent reached the end of Solomon Northup’s Twelve Years a Slave. Yet both these books appeared—and remained for some time—on the British bestseller lists.

“After collecting data between January and November 2014 from more than 21m[illion] users, in countries including Canada, the US, the UK, France, Italy and the Netherlands, Kobo found that its most completed book of 2014 in the UK was not a Man Booker or Baileys prize winner. Instead, readers were most keen to finish Casey Kelleher’s self-published thriller Rotten to the Core, which doesn’t even feature on the overall bestseller list…Kobo also revealed that the people of Britain were most likely to finish a romance novel, with 62% completion, followed by crime and thrillers (61%) and fantasy (60%). Italians were also most engaged by romance (74% completion), while the French preferred mysteries, with 70% completion.”

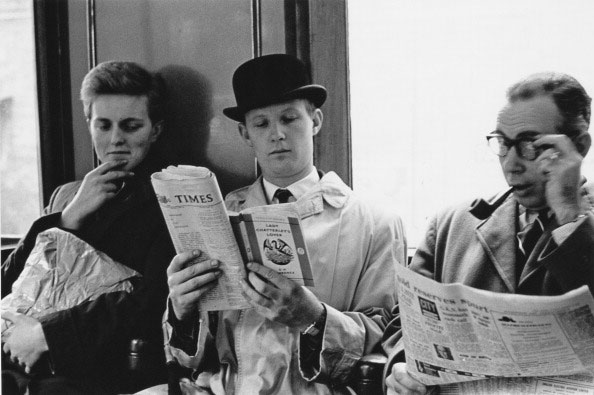

These statistics are certain to perplex writers who have so often been told by their publishers that a book’s popularity will not be affected in the least by costly newspaper or magazine advertising, but only by the more unpredictable, much desired—and free—publicity generated by “word of mouth.” Are we now to assume that readers are telling their friends to read books that they themselves have failed to finish? One used to hear that one advantage of the e-reader is that you could obtain a book such as Fifty Shades of Grey without the embarrassment of asking for it in a bookstore, and you could read it on your e-reader, on the subway, without anyone knowing what you are doing. I wonder if readers of Fifty Shades of Grey will now feel uneasy knowing that someone knows exactly which scenes they return to, and reread over and over?

For the time being, the data being gathered concerns general patterns of behavior rather than what happens between each of us and our personal E-readers. But we have come to live with the fact that anything can be found out. Today “the information” is anonymous; tomorrow it may well be just about us. Will readers who feel guilty when they fail to finish a book now feel doubly ashamed because abandoning a novel is no longer a private but a public act? Will it ever happen that someone can be convicted of a crime because of a passage that he is found to have read, many times, on his e-book? Could this become a more streamlined and sophisticated equivalent of that provision of the Patriot Act that allowed government officials to demand and seize the reading records of public library patrons?

As disturbing may be the implications for writers themselves. Since Kobo is apparently sharing its data with publishers, writers (and their editors) could soon be facing meetings in which the marketing department informs them that 82 percent of readers lost interest in their memoir on page 272. And if they want to be published in the future, whatever happens on that page should never be repeated.

Will authors be urged to write the sorts of books that the highest percentage of readers read to the end? Or shorter books? Are readers less likely to finish longer books? We’ll definitely know that. Will mystery writers be scolded (and perhaps dropped from their publishers’ lists) because a third of their fans didn’t even stick around long to enough to learn who committed the murder? Or, given the apparent lack of correlation between books that are bought and books that are finished, will this information ultimately fail to interest publishers, whose profits have, it seems, been ultimately unaffected by whether or not readers persevere to the final pages?

Advertisement

A young friend told me that there are people who buy books as lifestyle accessories, with only a vague intention of reading, but with the desire to demonstrate that they are the kind of person who reads Karl Ove Knausgaard. Certainly this declaration of tribalism and personal identity will be less impressive if Karl Ove is hidden on your coffee table under the covers of an e-book. In any case, the desire to own a book without necessarily reading or finishing it goes deeper than that: the reader may want to think of himself as a certain kind of person, a person who has read Donna Tartt or Twelve Years a Slave and has an opinion and can take part in the conversation. And it’s hardly a crime, unless the end of the book contains vital instructions for fixing a car or operating on the brain.

How much will this new knowledge affect readers themselves? Have they grown so accustomed to violations of their basic privacy that one more intrusion will not matter? Or will it matter a great deal?

I do know that these latest revelations will have an effect on me—just when I’d begun to think and say that, though I still much prefer reading what are now called “physical books,” I’ve become quite comfortable reading e-books, especially when I’m away from home and no longer need to be burdened by the tonnage of printed matter I used to carry with me out of terror of being stuck in an airport or train station with nothing to read. As soon as I get home, I’m putting away my e-book and opening my volume of Thackeray. I will happily bear its weight from room to room, from city to city; I’ll use a magnifying glass if necessary to cope with the tiny print. I don’t like the feeling that a stranger (electronic or human) is spying on my sojourn in Vanity Fair. Whether or not I finish a book will be a secret between me and my bookmark, and someday my grandchildren may be interested (or not) to see when I quit dog-earing the corners of the pages (a regrettable habit, I know) and at what point in a book my marginal annotations abruptly came to an end.

And yet I would be lying if I said I’ll stop reading e-books, just as much as I’d find it impossible, despite knowledge of possible surveillance, to give up email or logging on to the Internet. This is the post-Snowden predicament, as David Cole has pointed out.

Yesterday I couldn’t find my copy of The Good Soldier, and because I wanted it immediately and because I live a fifteen-minute drive from the nearest library, and thirty minutes from the nearest bookstore, I ordered it on my Kindle. I had it in under a minute. Already I seem to have learned to live with the fact that someone may be monitoring my progress through “the saddest story ever told” and that someone somewhere will know if I am enthralled or if I give up on Ford Madox Ford.