“There are two ways, perhaps, of looking at Francisco Goya,” writes Colm Tóibín in the Review’s December 18, 2014 issue. In the first version, Goya, who was born near Zaragoza in 1746 and died in exile in France in 1828, “was almost innocent, a serious and ambitious artist interested in mortality and beauty, but also playful and mischievous, until politics and history darkened his imagination…. In the second version, it is as though a war was going on within Goya’s psyche from the very start…. His imagination was ripe for horror.” We present below a series of prints and paintings from the show under review—the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston’s “Goya: Order and Disorder,” now closed—along with commentary on the images drawn from Tóibín’s piece.

—The Editors

Although Goya’s costume makes him appear the painter as performer, his face has nothing of the actor about it; he is almost comically ordinary as he sets about his work. His button nose lacks appeal. His hat, which has candleholders embedded in it, is too large. It is clear from the composition that he has no time for dullness. As you look at the eyes, the frank and pitying gaze, you get an effect that is quietly unsettling and disturbing.

This sombre self-portrait has elements of a Pietà, in which the stricken Goya, his left hand gripping the sheet in pain, is held in the tender arms of his doctor, with ghostly figures behind them. Goya’s instinct for theatricality, so apparent in the self-portrait made in the studio, returns now as an image of dark and unsparing self-exposure.

Light comes from the right of the painting above the cage; it appears as a gray-green glow and then as greenish shadow, leading to darkness on the left of the painting above the cats, becoming a sandy yellow at the boy’s feet and then a shadowy brown at the very front of the painting. The drama within this picture arises from an image of innocence and the sense of a great still artificiality that the boy exudes appearing to dominate the space and then slowly being undermined not only by the birds and the cats, but also by the background colors, which are ambiguous, uneasy, and almost ominous.

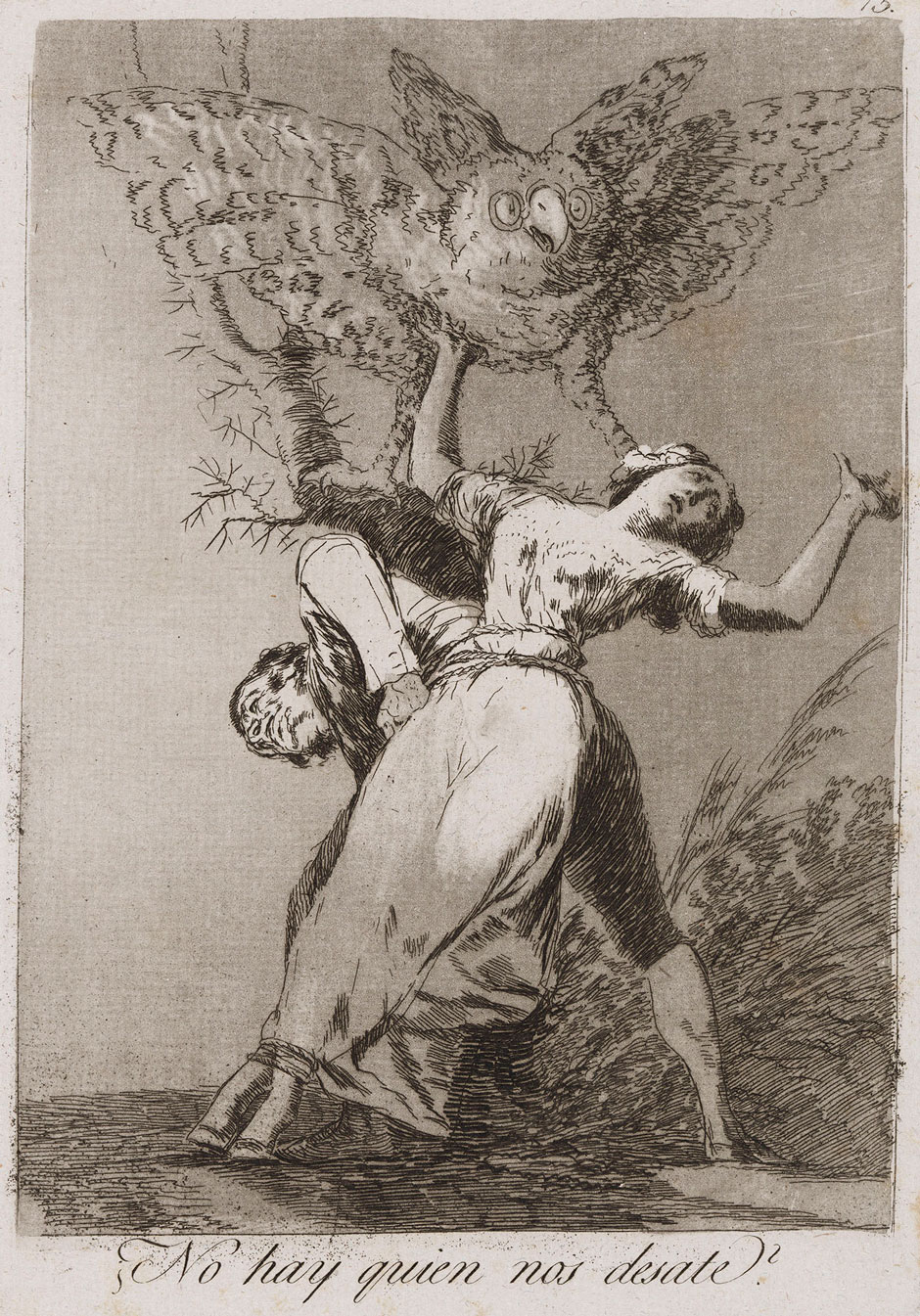

Goya’s relish for images of horror and decay can be seen in the series of etchings and aquatints called Caprichos, done between 1797 and 1799. If there are versions of love and innocence here, they come as sheer excitement and hilarious satire on what many others hold dear, as in Can’t Anyone Untie Us?, in which a distressed young woman and man seem to have been soldered into each other at the waist, with a thorny tree behind them, and a huge owl on their shoulders with its wings outspread.

This is not merely one of Goya’s best paintings of a person no longer young, it is simply one of his best paintings. María Antonia emerges here as a figure of fashion—her white shawl is painted in sumptuous and delicate detail, as is her dark dress with dark blue stripes and the blue rosette in her hair and the rose with blue ribbons on her chest. Her rings and a single long earring catch the light.

This portrait displays a powerful figure posing for the painter, and it also suggests someone engaged, engaging, almost sexual.

All of the madmen, under floating white light, seem mad in a lonely and personal way. Only the two men at the center locked in a wrestling match seem to recognize one another. The sense of isolation, which had elements of the comic or the awkward in an earlier royal painting, now is deeply frightening and disturbing.

This shocking painting shows dead and dying figures to the left, while on the right a group of soldiers have rifles directed at them, and in the middle there is a woman with a child, and she is fleeing from the rifles. Almost everything is designed to focus attention on her eyes in the act of looking backward in great terror.

Advertisement

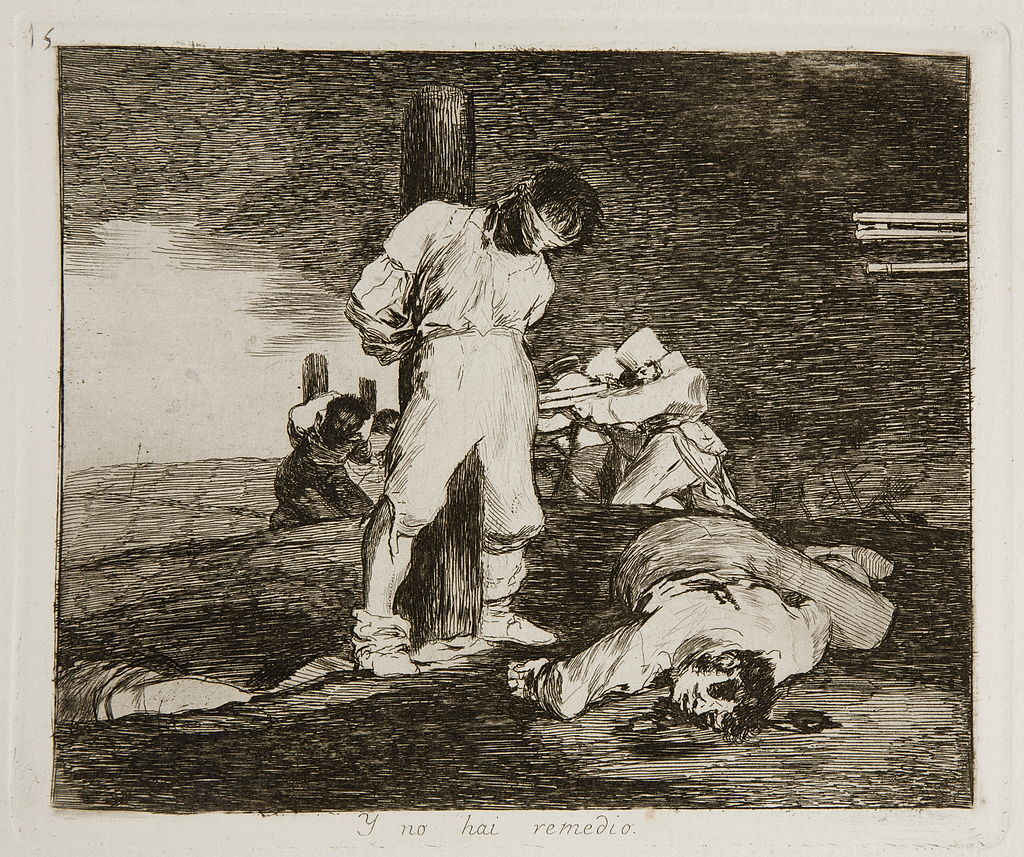

Here three simple lines to the right signify the barrels of rifles; we don’t see the soldiers at all, so that the blindfolded figure tied to a stake with his head bowed is all the more central and exposed. In the distance there are other figures being executed, and soldiers ready to fire.