It may be that everyone has their own Tomi Ungerer. The eighty-three-year-old graphic artist and illustrator’s work has been part of many people’s childhoods, others’ countercultures, still others’ outrage, and, at one point in his career, every straphanger’s New York. Mine is the artist whose late 1960s promotional posters for The Village Voice (“expect the unexpected”) still had pride of place in the newspaper’s offices when I began working there in the late 1970s.

Born in Strasbourg, Ungerer, who lived through the Nazi occupation, is a native of no-man’s land, as the term was used to describe a war zone, and a public artist, in the sense that, for a time, his primary gallery was the street. His work has since been enshrined in the Musée Tomi Ungerer, France’s first government-funded museum devoted to a living artist. “All In One,” Ungerer’s current US retrospective at the Drawing Center in Soho, is another first, surveying an oeuvre that encompasses illustrated children’s books, advertising campaigns, political posters, uncaptioned gag cartoons, gemütlich ink-wash landscapes, and sadomasochistic erotica. To these, curator Claire Gilman has added a sample of the juvenilia that Ungerer produced as a child in German-annexed Alsace.

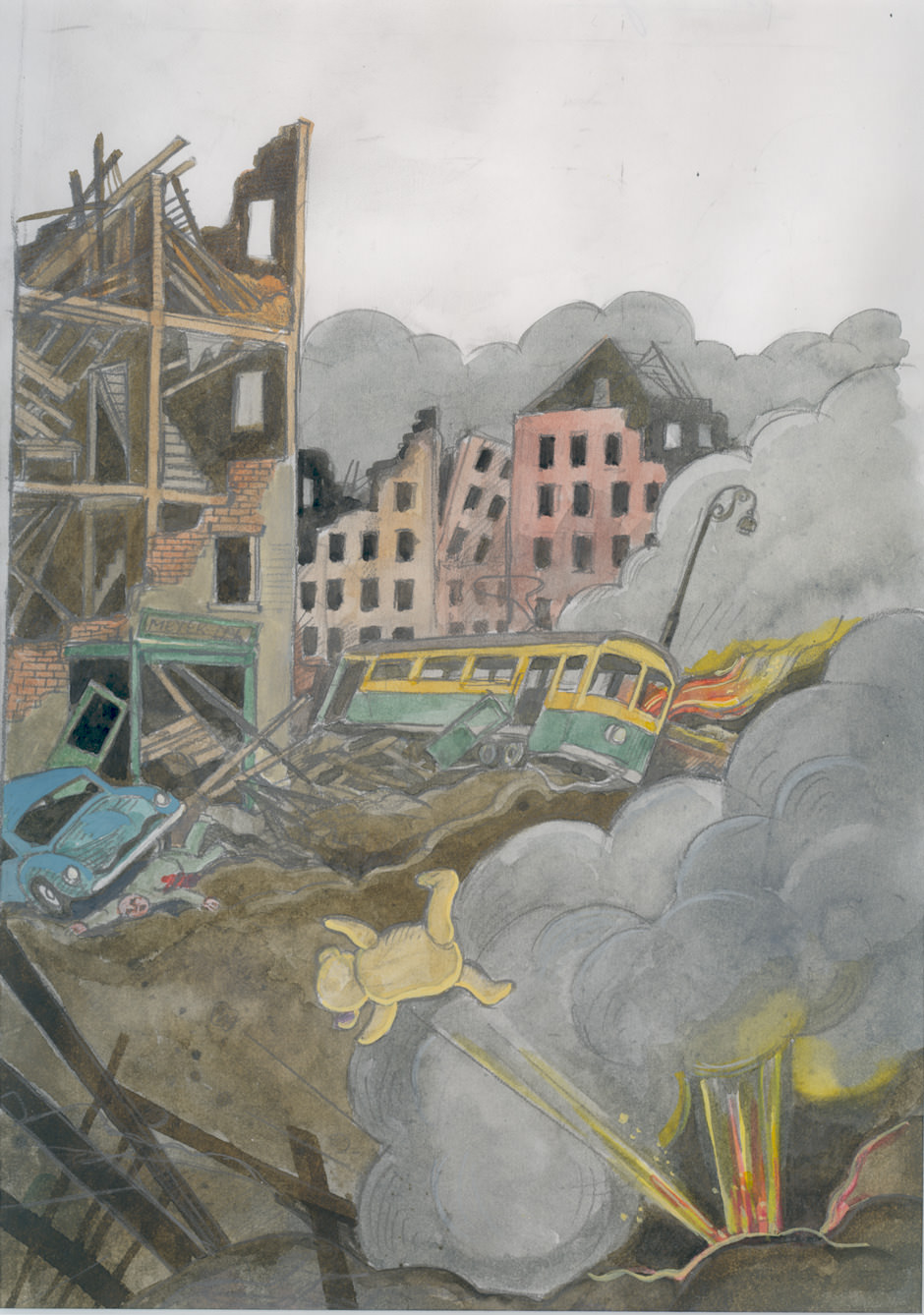

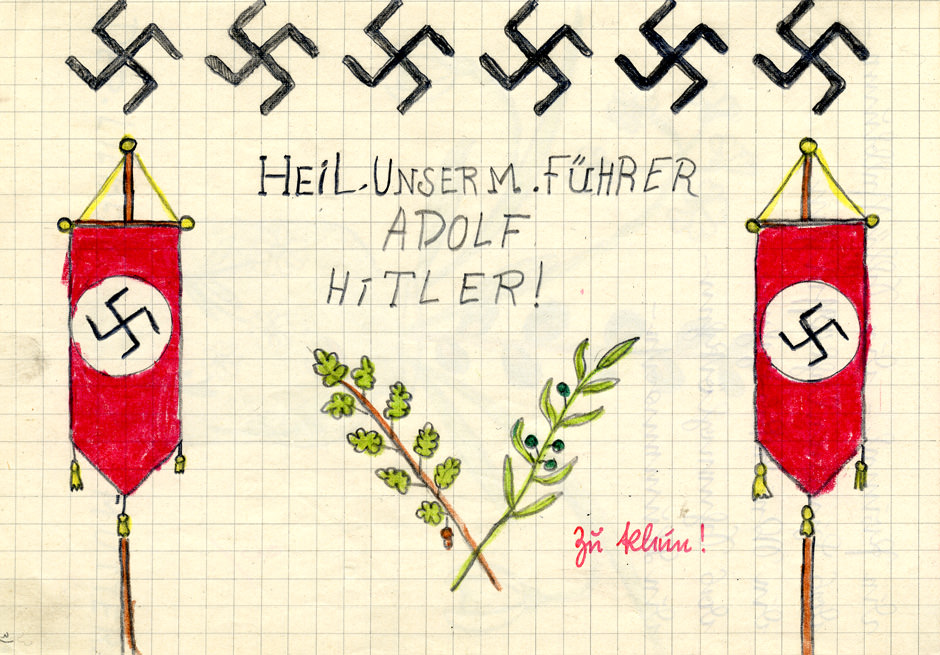

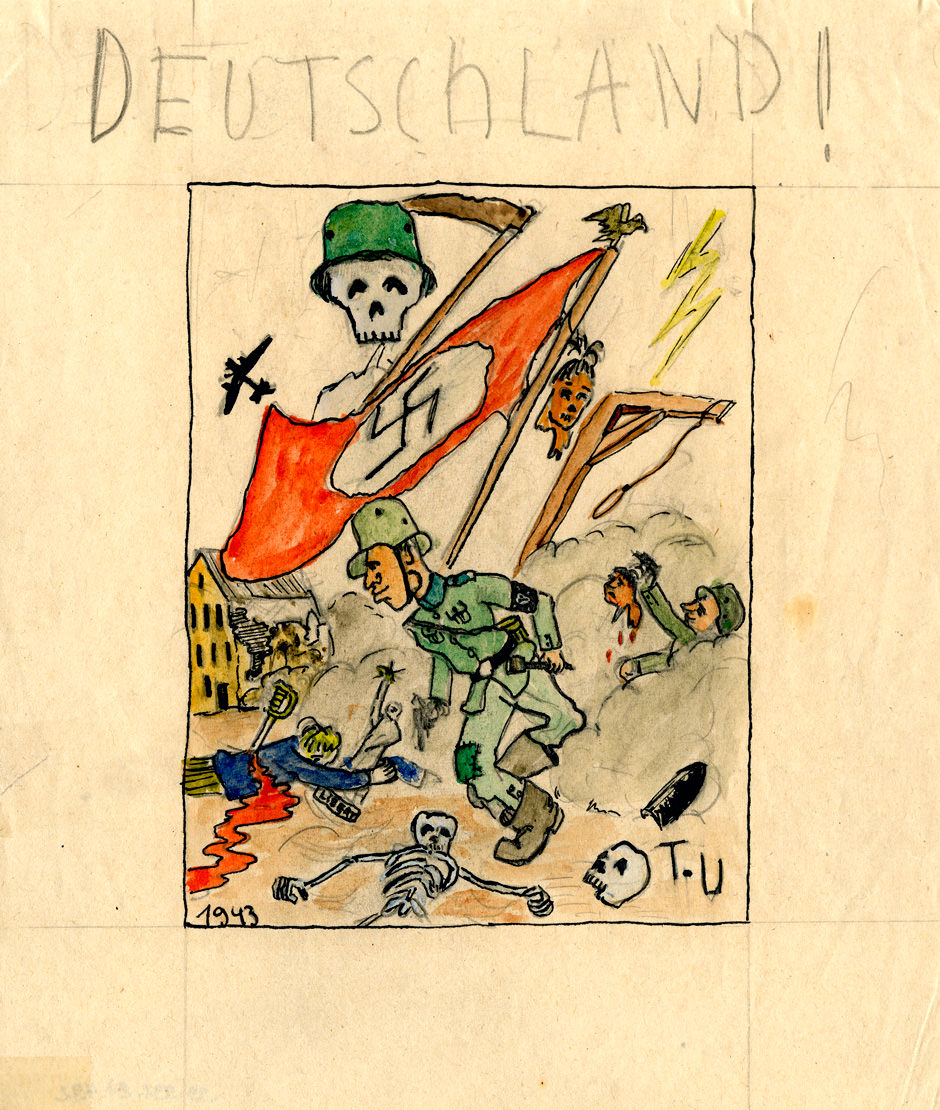

The half dozen or so examples of Ungerer’s schoolboy work cast a spell over the entire show. Blunt, fragile artifacts, one of which appears to be a sketch of a military engagement witnessed first-hand, the drawings illuminate the no-man’s land of Ungerer’s childhood and convey the sense of helpless rage that this ambiguously anti-authoritarian artist drew on and sublimated in his mature work. One fastidiously decorative arrangement of swastikas was a classroom assignments marked “Zu klein!” (Too small!) Another picture, titled Deutschland, is a vision of death and destruction suggesting the influence of Matthias Grünewald, whose Isenheim altarpiece is located in Colmar, where Ungerer attended school.

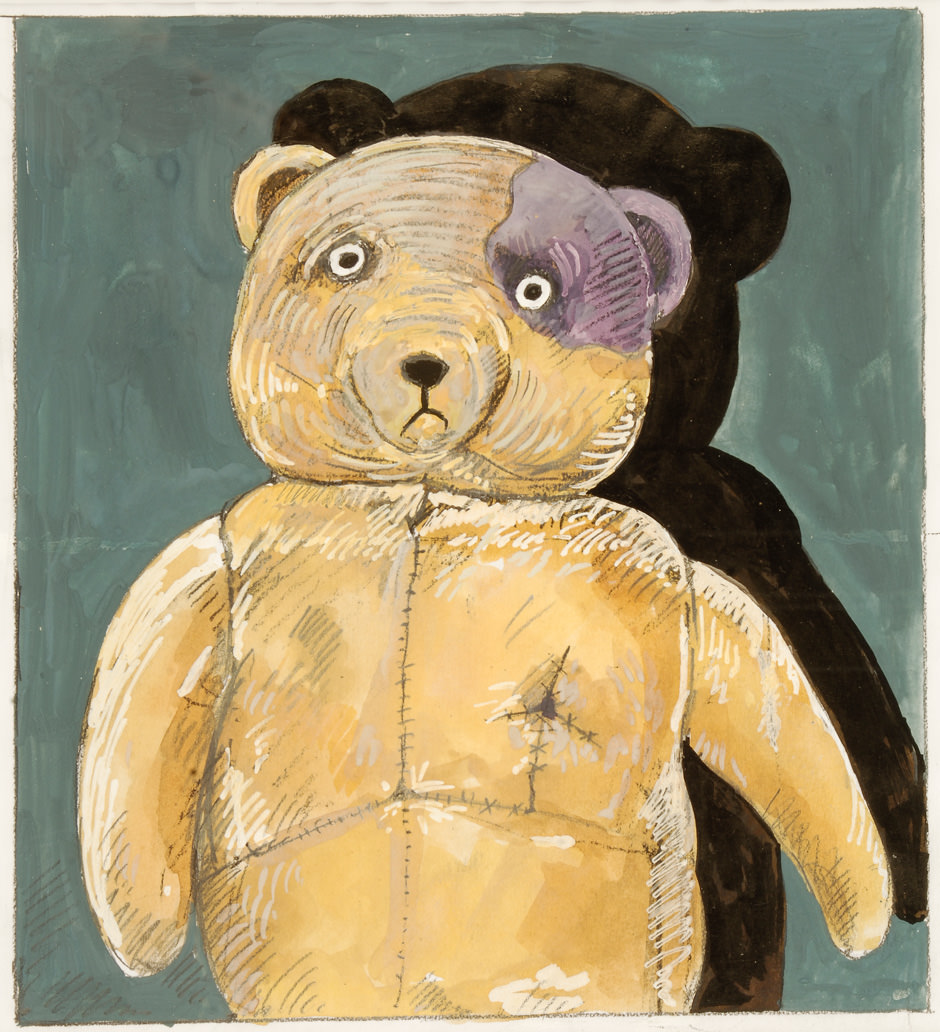

In his 1999 children’s book Otto: The Autobiography of a Teddy Bear, Ungerer imagines his own childhood teddy as a German toy given to and taken from a Jewish child. The bear survives World War II and winds up in New York—where fifty years after the war he is reunited with his original owner. The artist himself arrived in New York in the mid 1950s and almost immediately became a successful illustrator and author of children’s picture books—the earliest featuring a family of pigs—that were often compared to those of Maurice Sendak for their graphic invention, easy charm, and relatively dark humor. The Three Robbers (1961), which concerns a band of shadowy brigands who use their ill-gotten gains to create a sanctuary for a feisty orphan, is typically off-kilter and brilliantly designed.

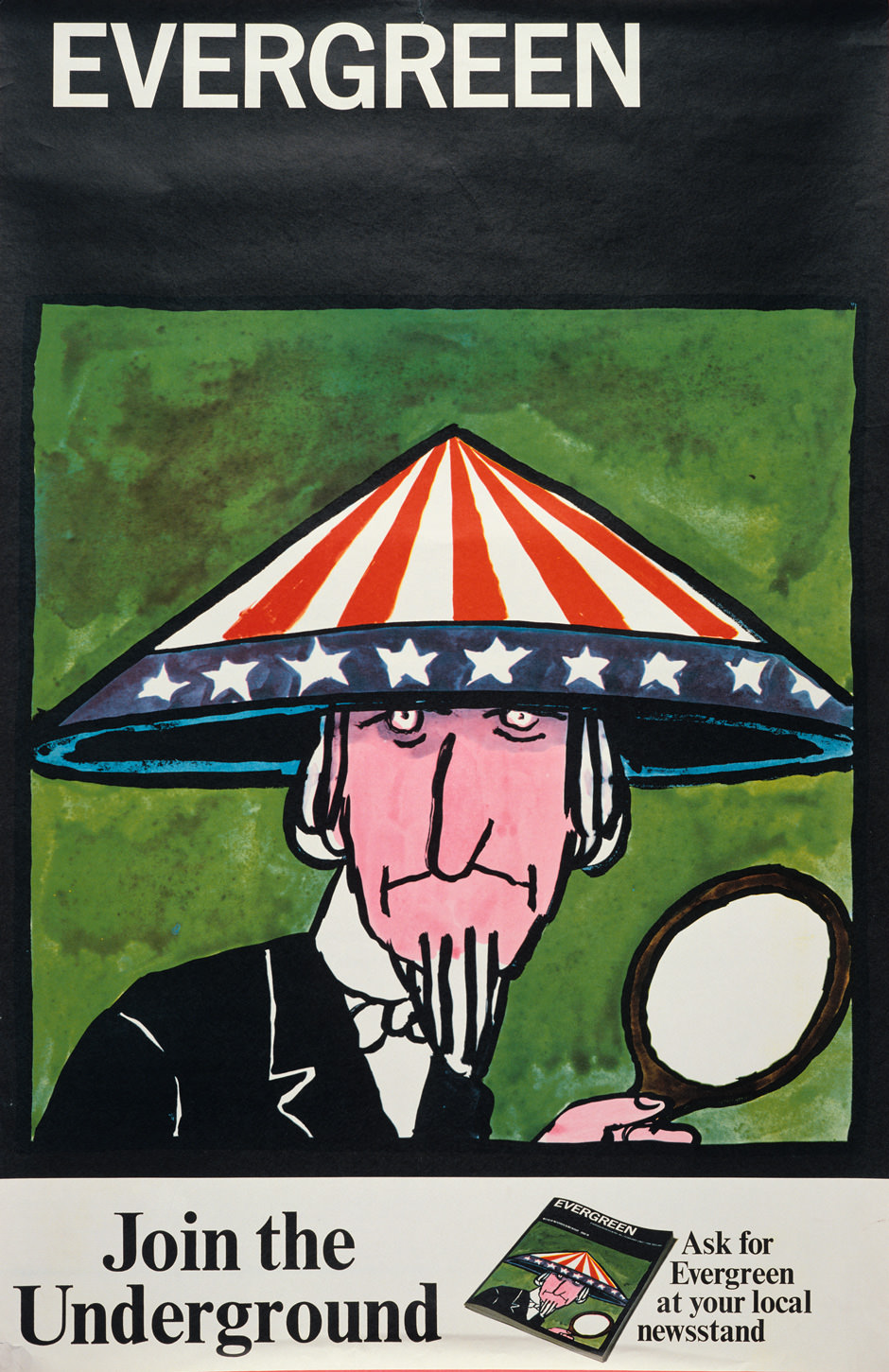

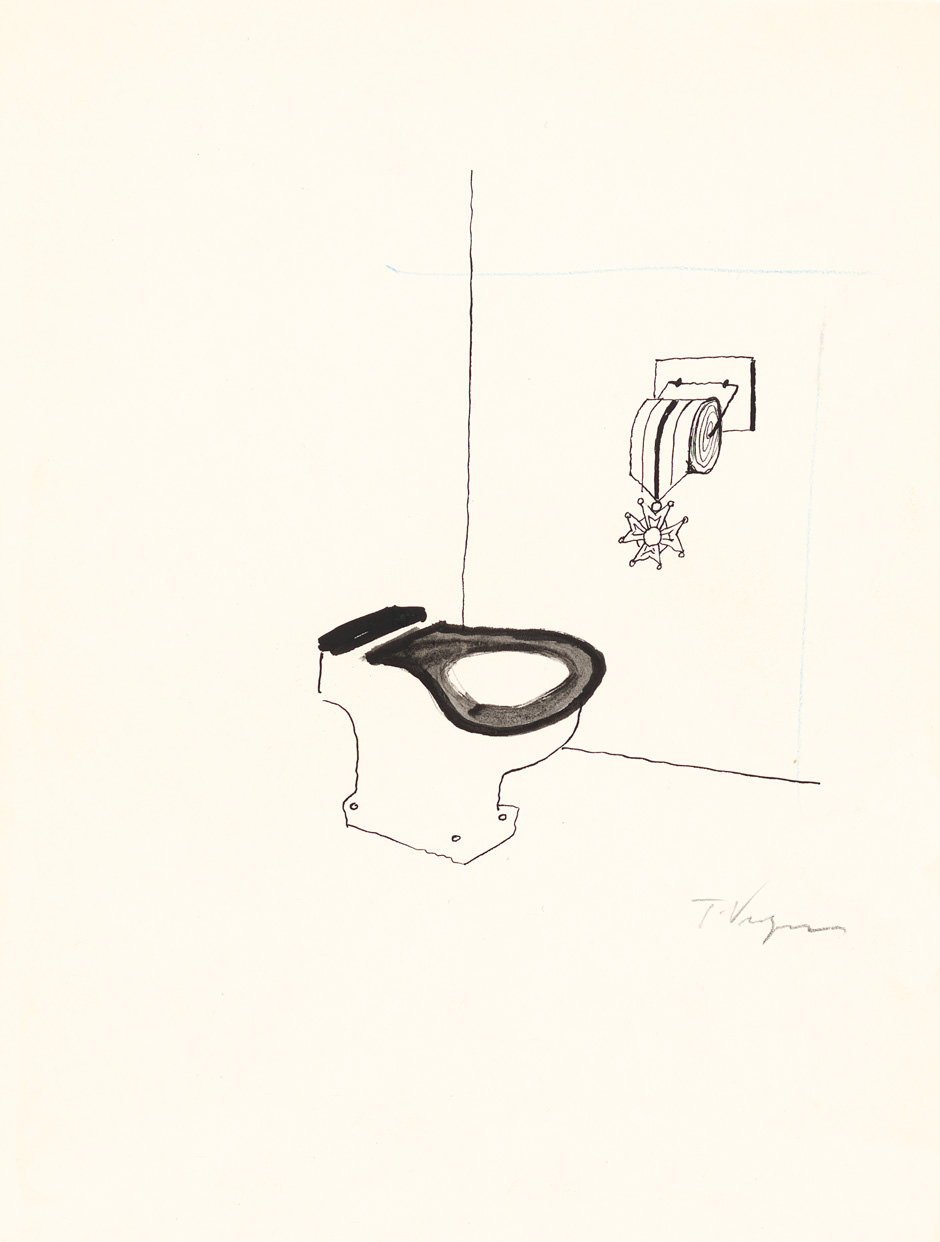

Ungerer subsequently carved out a place in New York’s Fun City landscape with the brashly colored, boldly simplified, insolently cryptic subway placards he made for The New York Times, The Village Voice, and the Evergreen Review. The last features a grimly paranoid-looking Uncle Sam in a star-spangled sampan hat, glaring out over a printed injunction to “Join the Underground.” Ungerer’s art—published in glossy magazines like Esquire, Playboy, and Sports Illustrated, chosen to illustrate the first English-language excerpt from The Tin Drum—was too prominent to be considered underground, although he used the term to describe the sketchbook he published in 1962. Its spidery drawings suggest a missing link between Saul Steinberg’s elegant ciphers and Jules Feiffer’s jittery scene-scapes. A few, like the military ribbon conceived as a roll of toilet paper, have the single-minded pow of the posters that were then his métier. In those days, Ungerer trafficked in shock and awe.

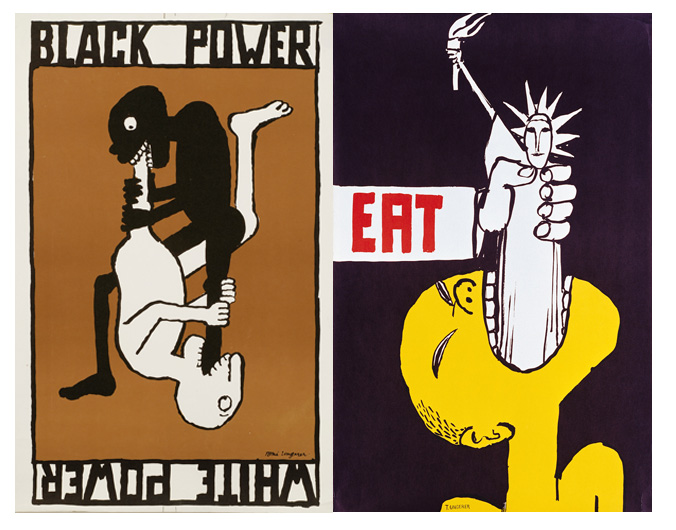

A sardonic poster for Stanley Kubrick’s 1964 Dr. Strangelove (not part of the exhibit) looks forward to the series of well-known anti-war posters, commissioned and rejected by Columbia University, that Ungerer self-published in the late 1960s. The most visceral, an agitprop gloss on Edvard Munch’s The Scream with the inscribed title Eat, has a bright yellow man force-fed a smirking replica of the Statue of Liberty. Ungerer’s iconic Black Power/White Power (1967), in which matched figures devour each other’s legs, is another icon of cultural revolution, once nearly as known as Milton Glazer’s trippy Bob Dylan poster or Richard Avedon’s solarized portraits of the Beatles.

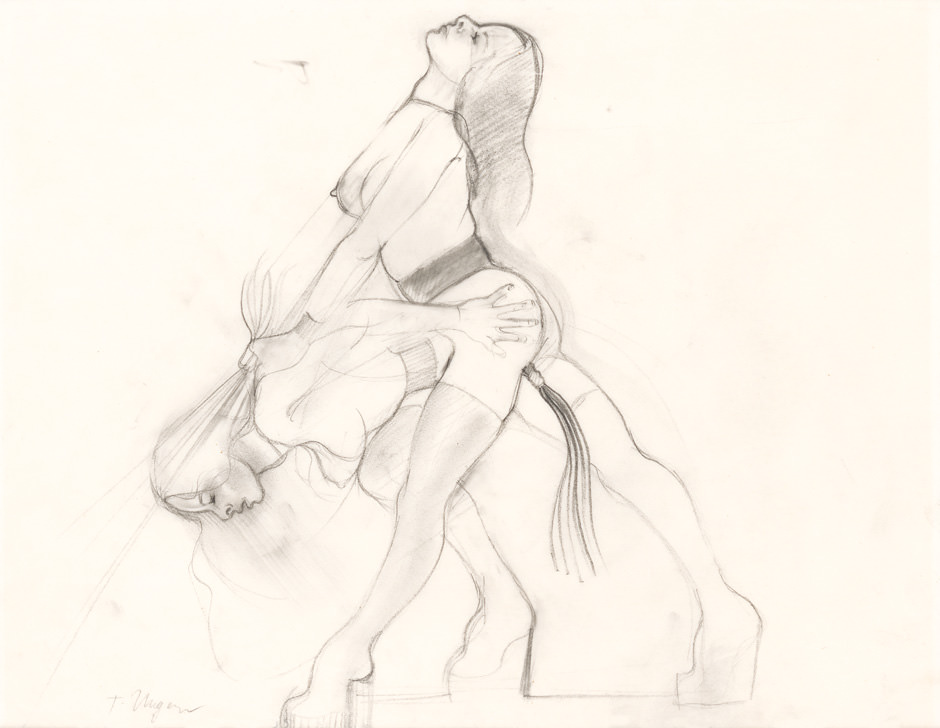

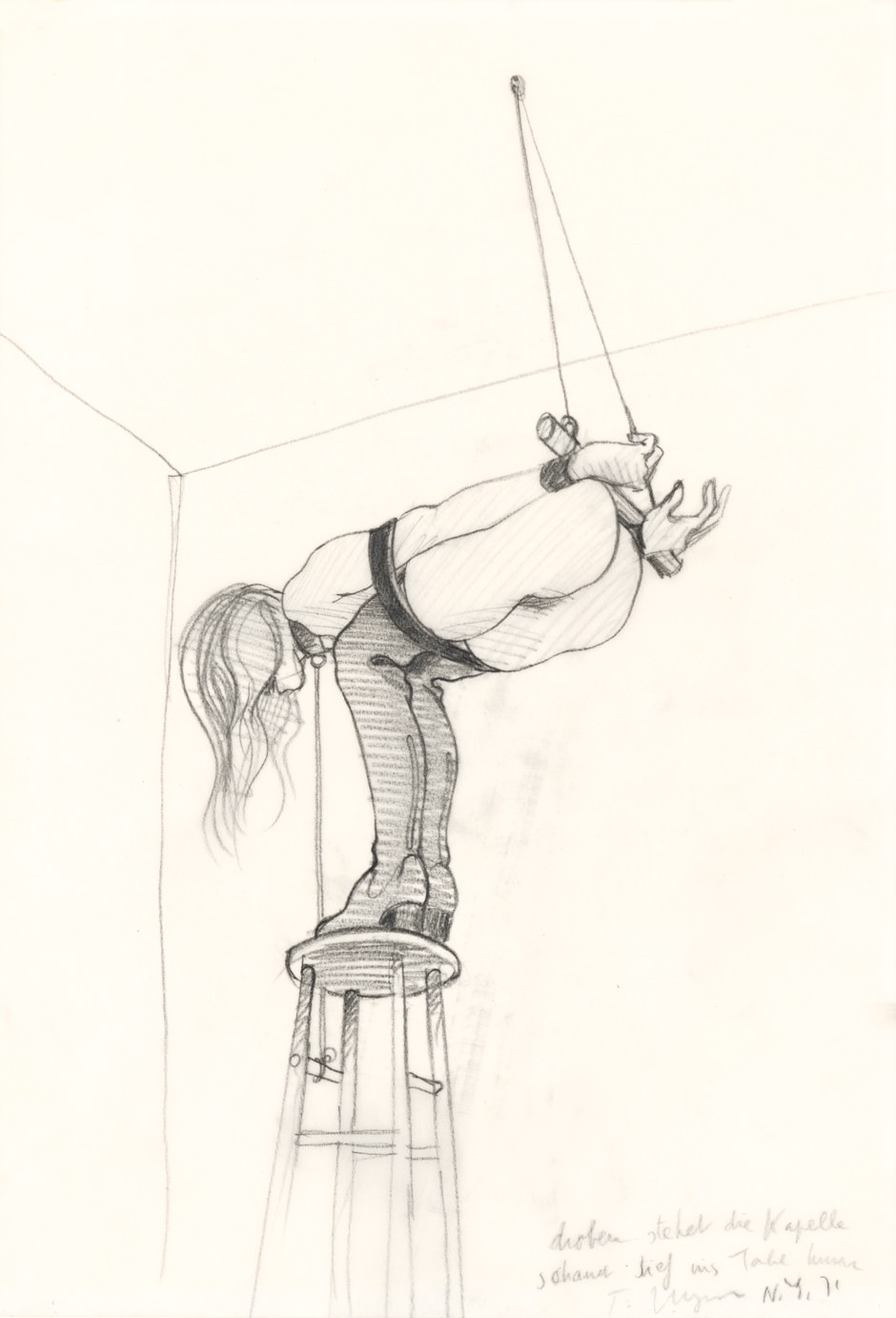

Black Power/White Power, with its Kama Sutra suggestion of simultaneous fellatio, has an undeniable sexual undercurrent, but Ungerer also addressed the sexual revolution head-on, assimilating the fluid line and stark patterning of Aubrey Beardsley in wildly phallocratic drawings of baroque pleasure devices and mechanical means of penetration. Published as an expensive folio, The Fornicon, these sprightly images—a literal, if perverse, expression of the desire to make love rather than war—provoked a strong negative reaction, effectively suspending Ungerer’s career as a children’s book artist (his works, he says, were banned from libraries) and precipitating his departure from New York, first for rural Nova Scotia and then for rural Ireland, where he showed a new interest in landscapes and domestic scenes. Before he left, however, Ungerer produced a suite of drawings depicting a young woman, usually alone, contorted in a variety of bondage positions that, more inquiry than assertion, are arguably the most accomplished and tender of his career. (Had Ungerer done the poster for The Night Porter, Liliana Cavani’s much reviled S&M love story might have had a far different reception.)

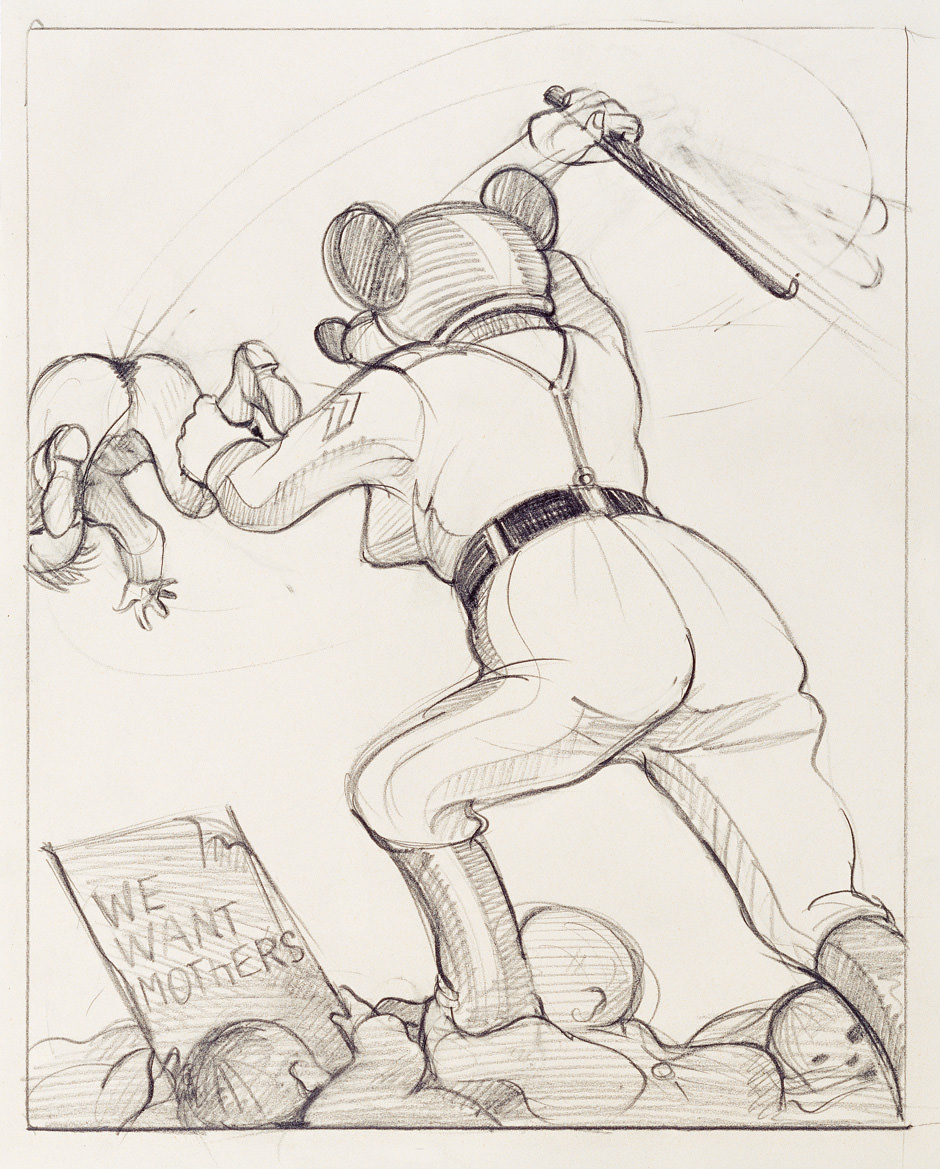

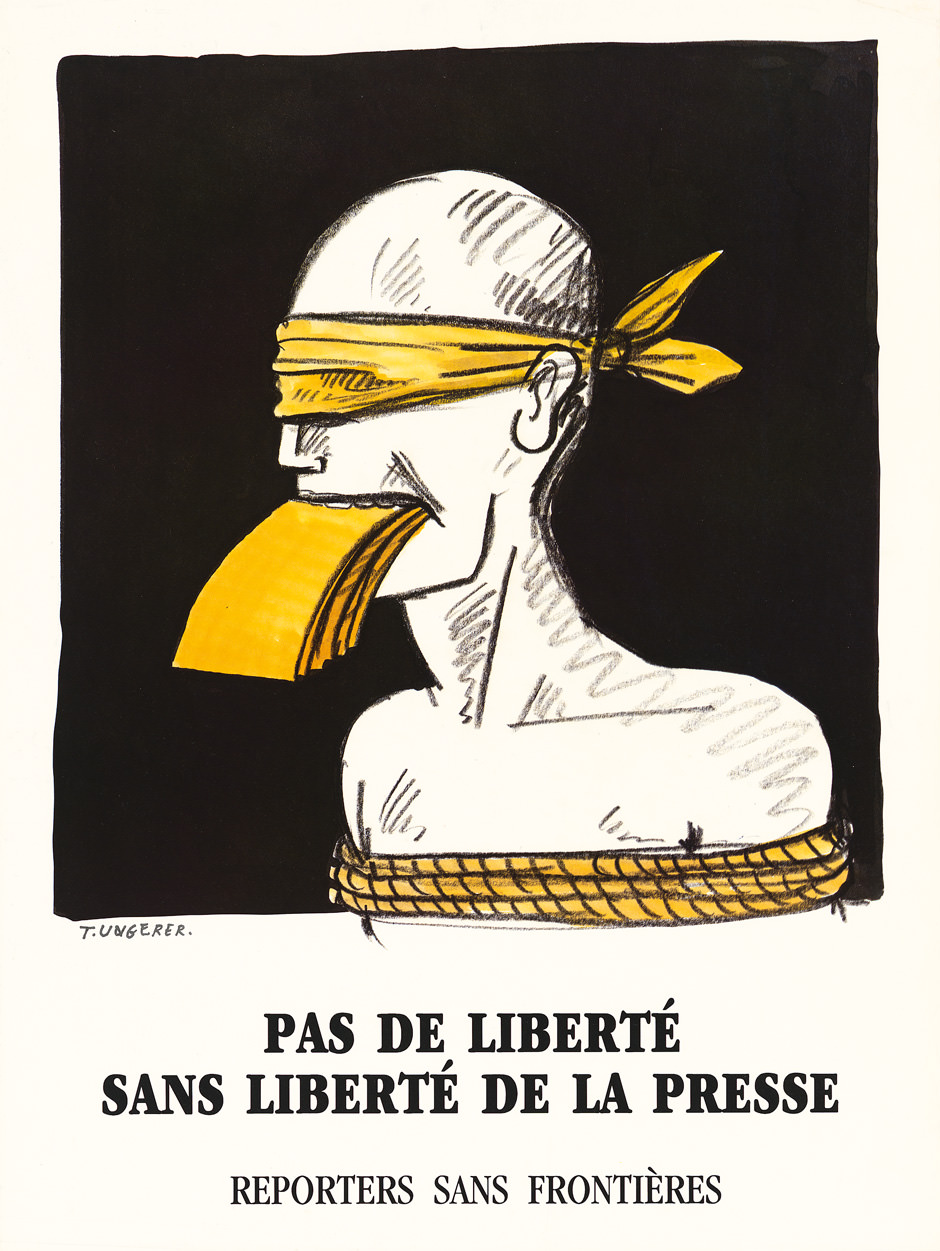

The bondage drawings are themselves confined to a separate room at the Drawing Center, along with a later series of artfully smudgy sketches of German dominatrices made while the artist was in residence in a Hamburg bordello. These tranquil studies, some reminiscent of Degas pastels, are idyllic compared to the resurgent political work of the 1980s and 1990s. A poster commissioned by the French organization Reporters Without Borders fuses the artist’s fascination with forcible restraint and his concern for free speech in the image of an apparently naked man, blindfolded, bound, and gagged with a reporter’s notebook. With their brutal Mickey Mouse figures, the drawings published as Babylon return to the remarkably assured knife-wielding, gun-toting Mickey—perhaps a self-portrait—that the precocious artist drew at age seven.

Given Ungerer’s history as a provocateur, it would have been surprising if he did not respond to the Charlie Hebdo massacre that occurred scarcely more than a week before his Drawing Center show opened. “All In One” includes an image if liberty crucified—it’s not one of Ungerer’s greatest drawings, but none is more heartfelt.

“Tomi Ungerer: All in One” is on view at the Drawing Center through March 22.