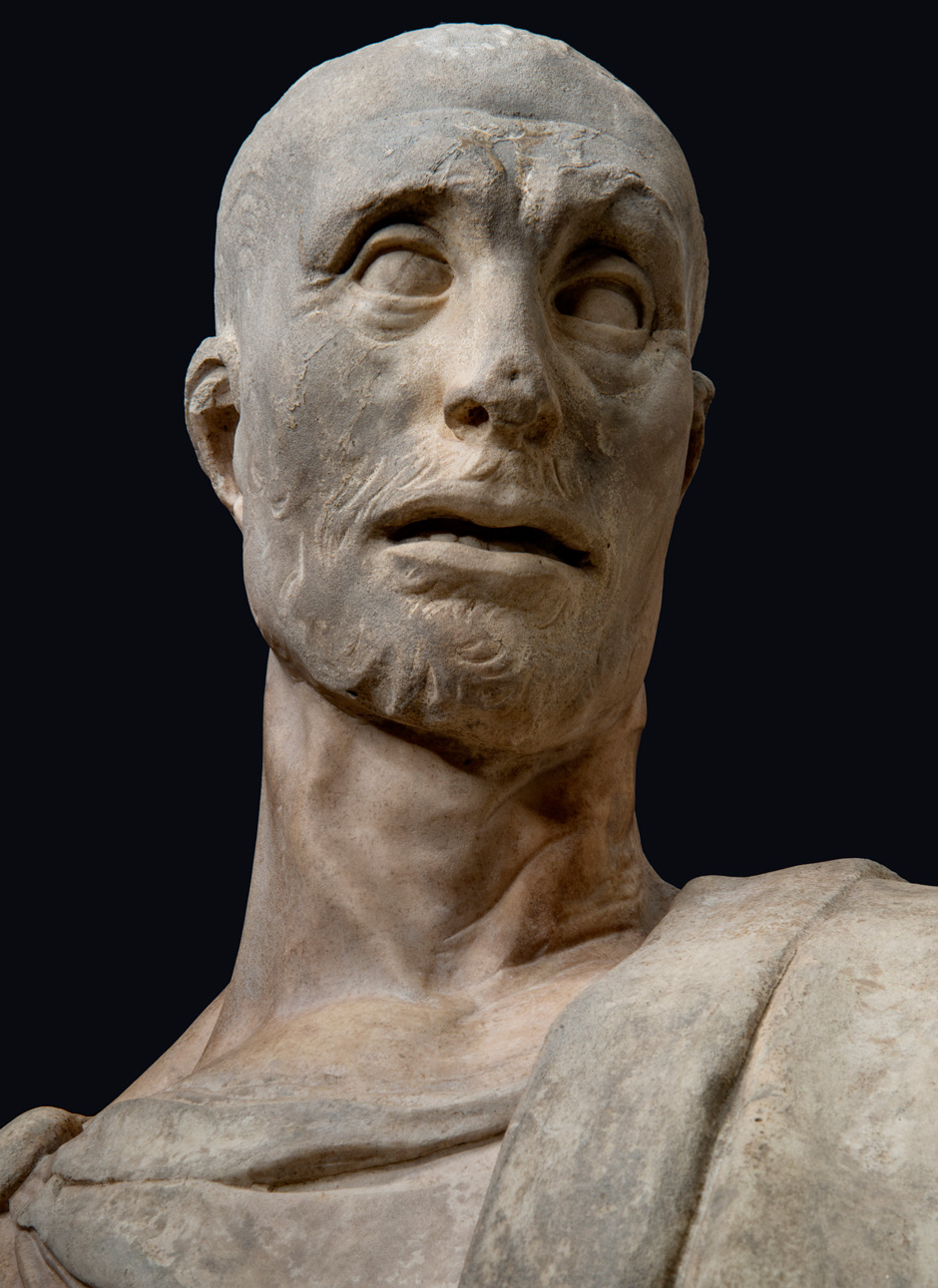

Among the works on view at the Museum of Biblical Art’s new show, “Sculpture in the Age of Donatello,” is the artist’s large sculpture of the Old Testament prophet Habakkuk, carved for the Campanile of the Florence Cathedral, likely between 1427 and 1436. “Speak, damn you, speak!” Donatello, we are told, repeatedly shouted at the statue while carving it. The dream of a statue that can speak or breathe or move is a fantasy shared by many cultures throughout time, and the story may be apocryphal. Still, it points to the fundamental appeal of Donatello’s sculptures: by some strange magic they seem to capture the phantom of life. Nowhere is this more evident than in the Habakkuk, which Vasari praised as “finer than anything else he ever made.” Even today it is often said to be the most important marble statue of the fifteenth century.

The first word of the book of Habakkuk can be translated as “burden,” and never has the trial of prophecy been more vividly represented than in Donatello’s statue. The artist portrays the holy man as hallowed and ravaged by the revelation that he has seen and must now convey. Wrapped in massive drapery that is at once weighty and floating, Habakkuk hovers and stares: a visitor from a realm where we mere mortals dare not go. His gigantic mouth, cut deep into his head and wide across his face, is open to speak and the words that it will emit are sure to be fearsome. The fiery text of his speech in the Bible is a call of warning and despair, as much as a prayer. It begins, “O Lord, how long shall I cry, and thou wilt not hear! even cry unto thee of violence, and thou wilt not save!” Near the end the book tells in brief but agonizing detail of what he has suffered for his divine vision: “When I heard, my belly trembled; my lips quivered at the voice: rottenness entered into my bones, and I trembled in myself.” Donatello’s statue embodies the sense of spiritual and physical terror in the biblical account.

According to a tradition repeated in Vasari, Habakkuk’s features were modeled on those of a Florentine citizen, and partly on this basis some art historians have credited the statue’s power to its element of realism. But as with so many of Donatello’s works, the credibility of this sculpture—its eerie vividness and palpable sense of presence—has as much to do with the distortion of actuality as with its imitation. As we can see in Habakkuk, Donatello was always significantly exaggerating the size of the most expressive features, especially the eyes, mouth, and hands. Furthermore, to overcome the lifelessness of marble or bronze, he made the outlines and surfaces of his sculptures undulate in irregular, uneven, and asymmetrical shapes so that the figure would look as if it were caught in a moment of change, like a living thing.

In the Bible Habakkuk warned against those who would seek to make idols, “Woe unto to him that saith to the wood, Awake; to the dumb stone, Arise.” Nevertheless, this seems to be exactly the kind of command Donatello gave his Habakkuk. Like a Renaissance magus, he believed the world was full of spirits, and he wanted his sculptures to palpitate with life.

Drawn from Andrew Butterfield’s review of “Sculpture in the Age of Donatello,” which will appear in a coming issue of The New York Review. The show is on view at the Museum of Biblical Art through June 14.